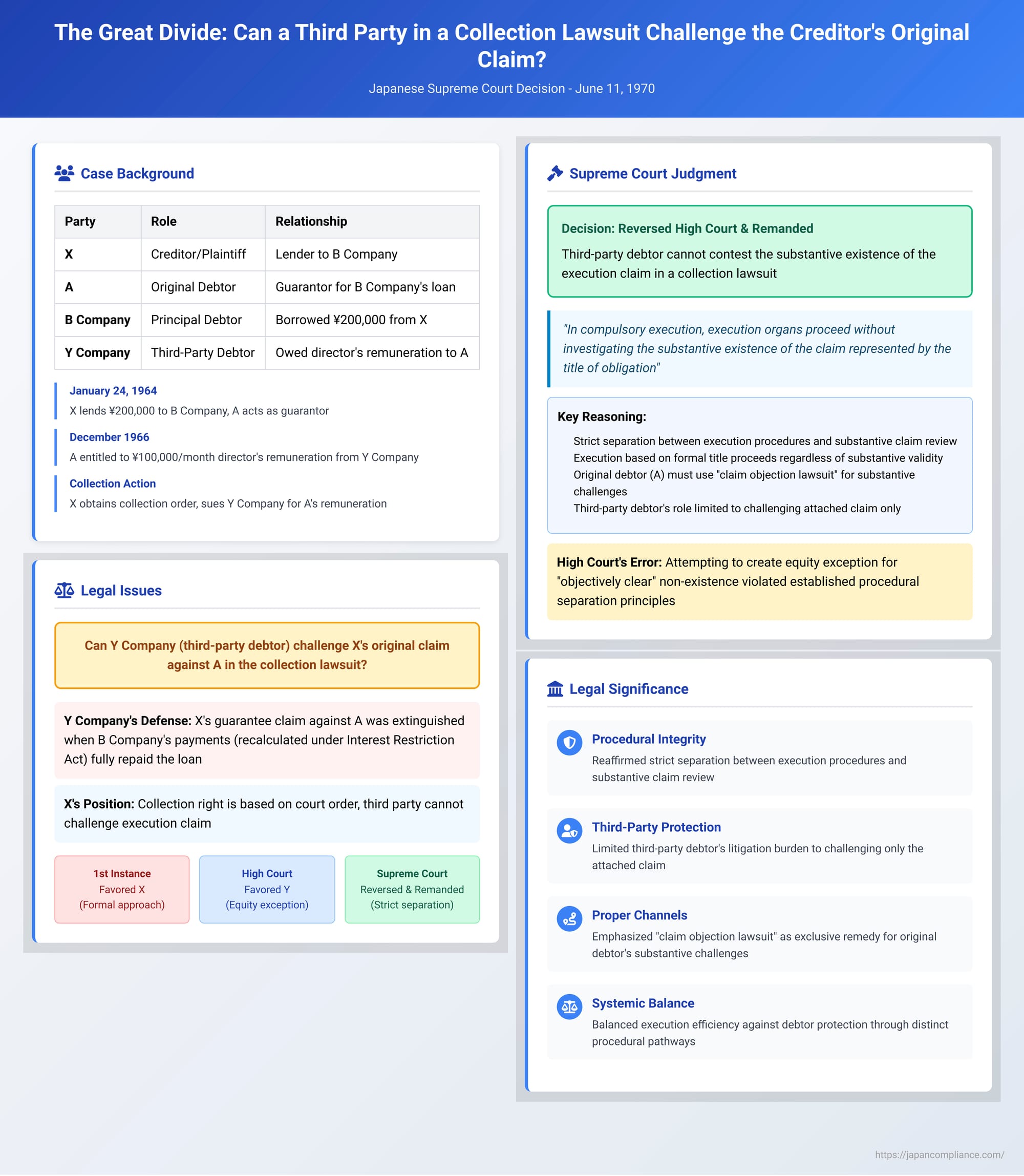

The Great Divide: Can a Third Party in a Collection Lawsuit Challenge the Creditor's Original Claim? A 1970 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: June 11, 1970

Case Name: Collection Claim Case

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Case Number: 1969 (O) No. 1075

Introduction

When a creditor (let's call them X) seeks to recover a debt from their debtor (A), they might discover that A is, in turn, owed money by a third party (Y). A common collection strategy is for X to attach A's claim against Y and then sue Y directly to "collect" that attached claim. This is known as a collection lawsuit (取立訴訟, toritate soshō). A crucial question then arises: In this lawsuit between X and Y, can Y (the third-party debtor) defend itself not only by challenging the existence or validity of the debt it owes to A (the attached claim), but also by attacking the legitimacy of X's original claim against A (the execution claim)?

This fundamental issue—the scope of defenses available to a third-party debtor in a collection lawsuit—was addressed by the Japanese Supreme Court in a significant decision on June 11, 1970. The case explored the strict procedural separation between debt execution and the substantive review of the underlying claims.

The Factual Scenario: A Loan, a Guarantee, and an Extinguished Debt?

The dispute involved the following parties and circumstances:

- X (Plaintiff/Appellant): The creditor.

- A (Original Debtor of X): The guarantor of a loan made by X. A was also a creditor of Y Company.

- B Company (Principal Debtor of X): The company that received the loan from X, for which A acted as guarantor.

- Y Company (Defendant/Appellee): The third-party debtor, which owed director's remuneration to A.

The timeline of events:

- The Loan and Guarantee: On January 24, 1964, X lent JPY 200,000 to B Company. A acted as a guarantor for this loan. The terms included monthly interest at 7% and daily late payment charges of 30 sen (0.3 yen). A notarial deed (公正証書, kōsei shōsho)—a type of enforceable instrument—was created documenting this loan and guarantee.

- A's Claim Against Y: From December 1966 onwards, A, in his capacity as a director of Y Company, was entitled to monthly director's remuneration of JPY 100,000 from Y Company.

- X's Collection Action: X, holding a claim against A for JPY 276,135 under the guarantee (based on the notarial deed), obtained a "collection order" (取立命令, toritate meirei – a feature of the old Code of Civil Procedure) from the court. This order allowed X to collect one-fourth of A's director's remuneration claim against Y Company, starting from December 1966, until X's claim against A was satisfied. Based on this collection order, X filed a collection lawsuit against Y Company.

- Y Company's Defenses: In the collection lawsuit, Y Company raised two main defenses:

- It denied that it owed any director's remuneration to A (challenging the attached claim).

- Crucially, as an affirmative defense, Y Company argued that X's underlying claim against A (the execution claim based on the guarantee) had actually been extinguished. Y asserted that the principal debtor, B Company, had made monthly payments of JPY 14,000 to X from January 1964 to June 1965, designated as interest and late charges. Y contended that when these payments were recalculated according to the mandatory rates under the Interest Restriction Act (利息制限法, risoku seigen-hō), and the excess amounts were applied to reduce the loan principal, B Company's original loan debt to X was fully repaid by June 1965. Consequently, A's guarantee obligation was also extinguished.

- X's Admission: Significantly, X (the plaintiff creditor) formally admitted the facts presented by Y Company regarding the payments made by B Company and their impact under the Interest Restriction Act, which effectively acknowledged that its original claim against A had been satisfied.

The Lower Court Tug-of-War: A Clash of Procedural Formalism and Substantive Justice

The lower courts took starkly different approaches:

- First Instance Court: Ruled in favor of X. It held that X's right to collect was derived from the court-issued collection order. Such an order, being part of the execution process, was deemed effective regardless of the actual existence or non-existence of the underlying execution claim (X's claim against A). Therefore, Y Company, as the third-party debtor, could not use the non-existence of the execution claim as a defense in the collection lawsuit. Y Company appealed.

- High Court: Reversed the first instance court and dismissed X's claim. The High Court acknowledged the "technical structure" of compulsory execution, where procedural matters are typically separated from substantive ones. Under this structure, a third-party debtor (Y) could challenge the existence of the attached claim (A's claim against Y) but not usually the existence or nature of the execution claim (X's claim against A). This separation, it noted, was generally accepted for reasons of procedural speed and simplicity.However, the High Court introduced a critical qualification. It reasoned that this technical separation finds its justification in the general probability that an execution based on a formally valid title of obligation (like X's notarial deed) is usually substantively just. But, if it becomes objectively clear from the facts that a formally valid title of obligation is substantively invalid (i.e., the underlying claim it represents is actually non-existent), then to deem the execution lawful merely because of the formal title would be an "abuse of the system." Specifically, allowing X to pursue a collection right against Y (who cannot formally dispute the X-A claim) when X's claim against A was admittedly extinguished would be contrary to the principle of good faith (信義則, shingisoku). Given X's admission that its claim against A had been satisfied, the High Court found that X's attempt to continue the execution and the collection lawsuit was impermissible. X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Clear Line: Strict Separation of Procedures

The Supreme Court, on June 11, 1970, reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings consistent with its opinion. It unequivocally sided with the principle of strict procedural separation.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Role of Execution Organs: In compulsory execution under the Code of Civil Procedure, the function of execution organs (like courts overseeing attachment and collection) is purely to carry out the execution. As long as a valid title of obligation (債務名義, saimu meigi – e.g., a final judgment, a notarial deed with an execution clause) exists, the execution organ is to proceed without investigating the substantive existence of the claim represented by that title, and without examining the legality of the claim's exercise (e.g., whether it constitutes an abuse of rights or violates good faith).

- Debtor's Remedy for Substantive Disputes: Because debtors might face execution based on a title that does not accurately reflect the substantive reality of the claim (e.g., the debt has been paid, as alleged here), they must be afforded an opportunity for a substantive review.

- The "Claim Objection Lawsuit" as the Proper Venue: However, conducting such a substantive review within the streamlined and rapid execution proceedings themselves is inappropriate. Instead, this substantive review is segregated into a separate, regular court proceeding known as a "claim objection lawsuit" (請求異議の訴え, seikyū igi no uttae – now under Article 35 of the Civil Execution Act). This is the designated procedure for a debtor (like A) to argue that the claim underlying the title of obligation is non-existent or invalid.

- Strict Distinction Between Procedural and Substantive Challenges: Thus, there is a sharp distinction between litigation concerning the execution process itself and litigation concerning the substantive existence or lawfulness of the claim contained in the title of obligation.

- Conclusion for the Collection Lawsuit: Therefore, in a collection lawsuit – which is an execution procedure – the third-party debtor (Y) cannot contest the substantive existence or the lawfulness of the execution claim (X's claim against A).

- High Court's Error: The High Court erred in its judgment by holding that a collection right cannot be exercised if the execution claim is "objectively and clearly" non-existent. This ruling was contrary to the established principle of separating execution procedures from the substantive review of claims, a review reserved for the claim objection lawsuit to be initiated by the debtor A.

The Prevailing Legal View and Its Justification

The Supreme Court's stance aligns with the traditional and still prevailing view among legal scholars in Japan. This view holds that a third-party debtor (Y) in a collection lawsuit cannot raise the non-existence of the execution claim (X's claim against A) as a defense.

The rationale, both under the old law (which had "collection orders") and the current Civil Execution Act (which provides for a "collection right"), is rooted in the nature of the execution process:

- The attaching creditor's authority to collect (their "collection right") is founded upon the court's attachment order, which is an official act of execution.

- The validity of this attachment order (and the ensuing collection right) is generally not affected by the substantive non-existence of the underlying execution claim, unless and until the attachment order is formally set aside or the execution is halted through proper procedures – primarily, a successful claim objection lawsuit brought by the original debtor (A).

- This is a matter of systemic design: the legal system provides distinct pathways for different types of challenges. The third-party debtor's role is not to litigate the merits of the dispute between the attaching creditor (X) and the original debtor (A).

This principle has been consistently applied by Japanese courts in subsequent cases, including those involving collection based on tax delinquency.

The "Objectively Clear Non-Existence" Conundrum: An Exception Rejected

The High Court's attempt to carve out an exception for cases where the execution claim's non-existence is "objectively clear" (especially, as in this case, due to the creditor's own admissions) resonated with some academic commentators. They argued:

- The practical justification for the strict separation of procedures (speed, simplicity) weakens when the non-existence of the execution claim is undeniable.

- Forcing a court to facilitate the collection of a debt that the creditor effectively admits has been paid (and in this instance, paid in a manner that initially violated the Interest Restriction Act) seems unjust and makes the court an unwilling participant in a flawed process.

- The attaching creditor can be seen as acting as a quasi-agent of the court in collecting the debt. If the creditor admits the very basis of this "agency" (their claim against the original debtor) is gone, then pursuing collection against the third party could be viewed as an abuse of the execution system or a violation of the principle of good faith/estoppel (not raising contradictory arguments).

However, the Supreme Court explicitly rejected this path. The primary counter-arguments are:

- Allowing such an exception would effectively permit the third-party debtor (Y) to raise issues that are statutorily reserved for the original debtor (A) in a claim objection lawsuit. This would blur the distinct procedural lines established by law.

- While the concept of "abuse of rights" might, in truly extreme and exceptional circumstances, have a role in execution proceedings, the mere fact that the execution claim's non-existence becomes clear (even through the creditor's admission in the collection suit) does not automatically transform the creditor's pursuit of the collection suit into an abuse of rights vis-à-vis the third-party debtor. The harm of the non-existent claim is primarily to the original debtor (A), who has the primary right and responsibility to challenge it.

Safeguards and Systemic Considerations

The Supreme Court's ruling means that the onus of challenging an execution claim that has been satisfied or is otherwise invalid lies squarely with the original debtor (A).

- Original Debtor's Protection: A can file a claim objection lawsuit (請求異議の訴え) to halt the execution and have the title of obligation declared unenforceable.

- Third-Party Debtor's Position: If the third-party debtor (Y) is compelled to pay the attaching creditor (X) in the collection lawsuit, Y is discharged from its debt to the original debtor (A) to the extent of the payment made. Thus, Y does not suffer a direct financial loss from making the payment itself (it's paying a debt it owed anyway, just to a different party). The primary "harm" to Y is being involved in litigation.

- Improving Dispute Resolution: From a systemic perspective of resolving disputes efficiently and fairly in one go, some scholars suggest enhancing the involvement of the original debtor (A) in the collection lawsuit between X and Y. This could be achieved through more proactive use of "litigation notification" (訴訟告知, soshō kokuchi – a mechanism where a party to a lawsuit notifies a third person whose legal interests might be affected, potentially allowing them to join or binding them to certain findings) or by interpreting the Civil Execution Act (Art. 157) to permit the court to order the original debtor (A) to participate in the collection lawsuit.

Conclusion: Upholding Procedural Integrity

The Supreme Court's June 11, 1970, decision strongly reaffirmed the principle of procedural separation in Japanese civil execution law. In a collection lawsuit brought by an attaching creditor against a third-party debtor, the third-party debtor cannot defend by challenging the substantive validity of the underlying execution claim (the debt owed by the original debtor to the attaching creditor). Such challenges are reserved for the original debtor through a specific procedure: the claim objection lawsuit.

While the High Court's attempt to introduce an equitable exception for cases where the execution claim's non-existence is "objectively clear" (particularly due to the creditor's own admissions) had some appeal, the Supreme Court prioritized the integrity and clarity of the established procedural framework. This framework is designed to ensure that execution based on a formally valid title proceeds swiftly, while providing a distinct and proper channel for debtors to raise substantive objections to the claims underlying those titles. The third-party debtor's protection lies in their discharge against the original debtor upon payment to the attaching creditor, not in litigating the merits of a claim to which they are not a primary party.