The "GEORGIA" Coffee Case: Defining "Place of Origin" in Japanese Trademark Law

Judgment Date: January 23, 1986

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Case Number: Showa 60 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 68 (Action for Rescission of a Trial Decision)

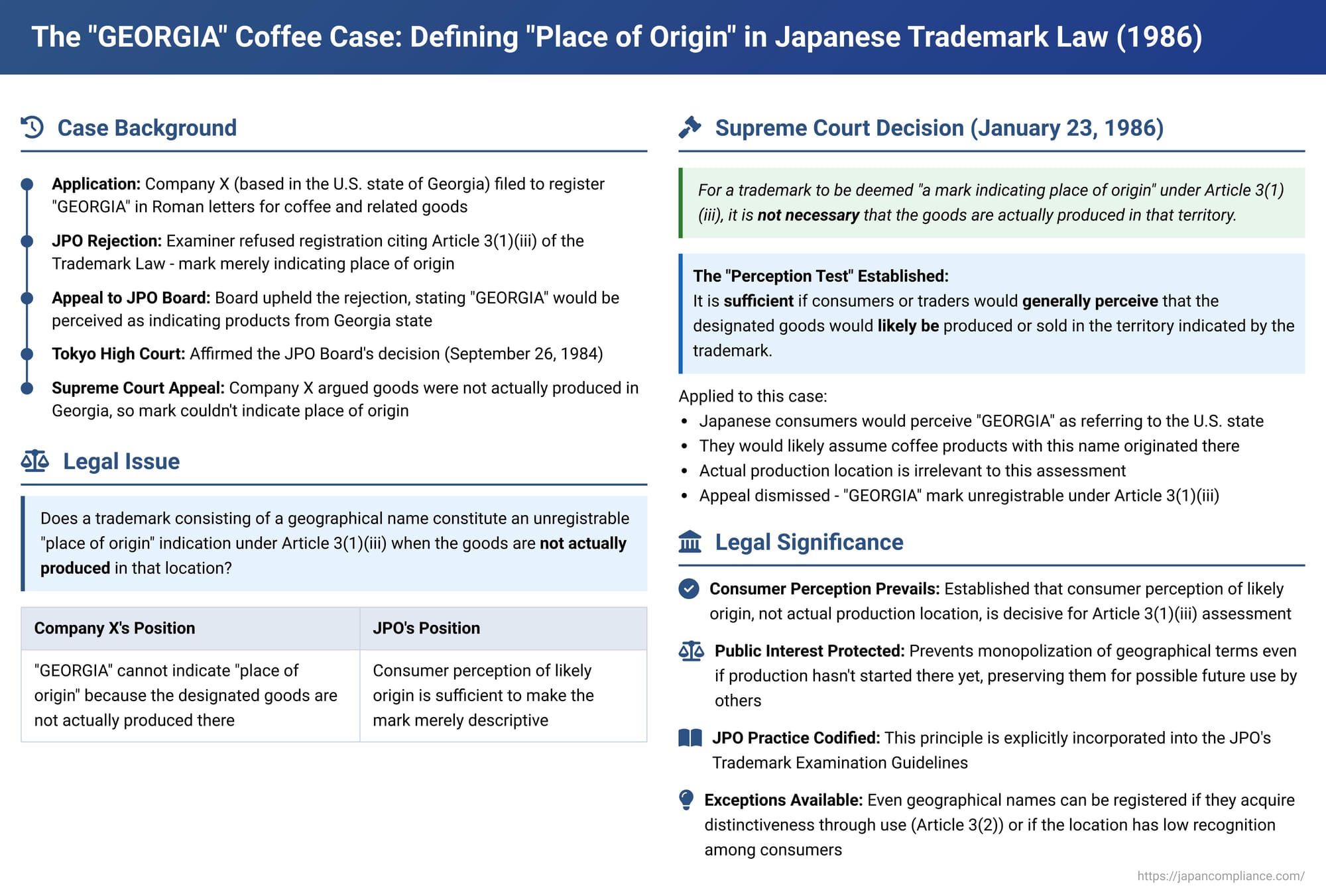

The "GEORGIA" case stands as a pivotal decision in Japanese trademark law, particularly for its clarification of what constitutes a "place of origin" or "place of sale" under Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3 of the Trademark Law. This provision generally bars the registration of trademarks consisting solely of such geographical indications. The Supreme Court's interpretation in this case—that the perception of likely origin by consumers is sufficient, rather than requiring actual production in that location—has profoundly shaped the examination and enforcement of geographical trademarks in Japan.

The Path to the Supreme Court: A Bid to Register "GEORGIA"

The case began when Company X, a corporation with its main office in the U.S. state of Georgia, filed a trademark application in Japan for the word "GEORGIA" written horizontally in Roman letters. The designated goods for this proposed trademark were "tea, coffee, cocoa, coffee beverages, [and] cocoa beverages," falling under Class 29 of the goods classification at the time.

The Japan Patent Office (JPO) examiner rejected the application, determining that it fell under Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3 of the Trademark Law. This article prevents registration of trademarks that consist solely of a mark indicating, in a common way, the place of origin, place of sale, quality, raw materials, efficacy, use, quantity, shape, price, or method or time of production or use of the goods, or the place of provision, quality, articles used in provision, efficacy, use, quantity, modes, price, or method or time of provision of services. The focus here was on "place of origin" or "place of sale."

Company X appealed the examiner's rejection to the JPO's appeal board. However, the appeal board upheld the original decision to refuse registration. The board reasoned that the mark "GEORGIA" would readily make Japanese traders and consumers think of the U.S. state of Georgia. Furthermore, because the food processing industry was known to be prosperous in that state, the board concluded that traders and consumers, upon seeing "GEORGIA" used on the designated goods (like coffee or tea), would merely perceive it as an indication that these products were manufactured in the state of Georgia. They would not, therefore, recognize "GEORGIA" as a distinctive mark capable of identifying Company X's goods from those of other businesses.

Undeterred, Company X filed a lawsuit with the Tokyo High Court seeking the cancellation of the JPO appeal board's decision.

The Tokyo High Court's Stance

The Tokyo High Court, in its judgment on September 26, 1984, affirmed the JPO appeal board's decision to refuse the trademark registration. The High Court elaborated on its reasoning:

- It acknowledged that "Georgia" is indeed the name of a state in the southeastern United States.

- Crucially, the court considered the general knowledge of Japanese consumers and traders regarding the United States at that time. It posited that when these individuals encounter the trademark "GEORGIA," the vast majority would recognize it as representing a geographical location within the U.S., even if not all of them could precisely identify it as a state.

- Based on this likely perception, the High Court made a key assertion: even if Company X could prove that the designated goods (coffee, tea, etc.) were not actually produced in the state of Georgia, this would not automatically make the mark registrable. The court stated that unless there were "special circumstances" suggesting that the name "Georgia" could not possibly indicate the origin of such goods, traders and consumers would still likely assume the goods were produced there.

- The High Court found no evidence of such "special circumstances" in this case.

- Therefore, it concluded that the trademark "GEORGIA" consisted solely of a mark indicating the place of origin of the designated goods, displayed in a common manner, and was thus unregistrable under Article 3(1)(iii).

Company X then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Japan. Its core argument on appeal was that because the designated goods were not actually produced in the state of Georgia, the trademark "GEORGIA" could not be considered to indicate a "place of origin" within the meaning of Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3 of the Trademark Law.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Clarification

On January 23, 1986, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court delivered its judgment, dismissing Company X's appeal. The Court's reasoning provided a definitive interpretation of the requirements under Article 3(1)(iii):

The Supreme Court held that for a trademark application to be deemed "a trademark consisting solely of a mark indicating, in a common way, the place of origin or place of sale of the goods" under Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3, it is not necessarily required that the designated goods are actually produced or sold in the territory indicated by the trademark.

Instead, the Court ruled that it is sufficient if it is generally perceived by consumers or traders that the designated goods would likely be produced or sold in the territory indicated by the trademark.

Applying this principle to the "GEORGIA" application, the Supreme Court looked at the facts as lawfully established by the Tokyo High Court. It concluded that consumers or traders in Japan encountering the trademark "GEORGIA" in connection with the designated goods—coffee, coffee beverages, and the like—would indeed generally perceive these goods as likely being produced in a place called "Georgia" within the United States.

Consequently, the Supreme Court affirmed that the trademark "GEORGIA" fell under the scope of Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3 and was therefore unregistrable. The High Court's judgment, which had reached the same conclusion, was deemed justifiable and free of any legal error.

Why This Interpretation? The Rationale Behind "Perception"

The Supreme Court's decision in the GEORGIA case did not explicitly detail the foundational policy reasons for its interpretation in this particular judgment. However, the accompanying commentary and the established understanding of trademark law, referencing the earlier "Waikiki case" (Supreme Court, April 10, 1979), shed light on the underlying principles.

The Waikiki case established that descriptive marks, including geographical indications, are generally unregistrable for two main reasons:

- Lack of Distinctiveness: Such marks typically fail to perform the essential function of a trademark, which is to distinguish the goods or services of one undertaking from those of others. They are seen as describing a characteristic of the product (e.g., its origin) rather than indicating a specific commercial source.

- Public Interest (Anti-Monopoly): Terms that describe product characteristics, including geographical origin, are often necessary or useful for all traders in the relevant market to use. Granting an exclusive, monopolistic right to one entity to use such a descriptive term would be detrimental to fair competition and the public interest.

While the "lack of distinctiveness" argument might intuitively seem linked to whether a term is already commonly used (perhaps because a place is an actual production site), the GEORGIA ruling—by focusing on perception of likely origin rather than actual origin—highlights the strong role of the public interest/anti-monopoly rationale. The idea is that if the public or trade circles perceive a term as a geographical indicator for certain goods, it would be against the public interest to allow that term to be monopolized, even if the location isn't currently a known major production site for those specific goods. This prevents the pre-emptive appropriation of terms that others might legitimately need to use descriptively in the future.

Furthermore, there's a practical consideration. If Article 3(1)(iii) were interpreted to require proof of actual production or sale in the named location, JPO examiners would face an almost impossible burden. Verifying the precise production status of all designated goods for every trademark application involving a geographical term would be a massive, complex, and often unfeasible undertaking at the examination stage. The "perception" standard is more administrable.

Impact and Practical Application: The Legacy of the GEORGIA Case

The GEORGIA case's interpretation of "place of origin" and "place of sale" has become the established standard in Japan and is consistently followed by lower courts and reflected in the JPO's own examination practices.

Trademark Examination Guidelines:

The JPO's Trademark Examination Guidelines (currently in their 15th revised edition as of the provided commentary) explicitly incorporate the principle from the GEORGIA decision. The guidelines state:

- (1) If a trademark consists of a domestic or foreign geographical name (such as a country, former country, capital city, region, administrative division like a prefecture/city/town, state, county, province, well-known commercial street, tourist spot including its surrounding area, lake, mountain, river, park, or a map representing these), and if traders or consumers would generally perceive that the designated goods are likely produced or sold, or designated services are likely provided, in the land indicated by that geographical name, then it is judged to be a "place of origin," "place of sale," or "place of provision of services" under Article 3(1)(iii).

- (2) Similarly, if a trademark consists of the name of a country (including abbreviations or former names of existing countries) or another famous domestic or foreign geographical name, it is generally judged to be an indicator of "place of origin," "place of sale," or "place of provision of services".

Subsequent Court Decisions Illustrating the Principle:

Numerous IP High Court decisions have applied this "perception-based" test:

- "Tokyo Milk" (東京牛乳): A trademark "Tokyo Milk" for "milk" in Class 29 was found to indicate a place of origin or sale (IP High Court, September 30, 2009). Consumers would likely perceive it as milk from Tokyo.

- "HOKOTABAUM": A trademark "HOKOTABAUM" for "baumkuchen" (a type of cake) in Class 30 was also found to indicate a place of origin or sale (IP High Court, October 12, 2016). Hokota is a city in Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan, and consumers might associate the product with that location.

- Low Recognition Defeats Geographical Indication Claim (SIDAMO, YIRGACHEFFE): In cases involving applications for "SIDAMO," "シダモ" (Sidamo in Katakana), "YIRGACHEFFE," and "イルガッチェフェ" (Yirgacheffe in Katakana) as trademarks for "coffee" and "coffee beans" in Class 30, the IP High Court (March 29, 2010) held that these terms did not fall under Article 3(1)(iii). Although Sidamo and Yirgacheffe are coffee-growing regions in Ethiopia, the court noted that these names were not listed in school atlases, general maps, or standard dictionaries and encyclopedias available in Japan. This indicated a low level of recognition of these names as geographical locations among Japanese consumers and traders, meaning they wouldn't be perceived as primarily indicating origin.

- Recognition Through Use (美ら島 - Chura Shima): Conversely, the trademark "美ら島" (Chura Shima, an Okinawan term meaning "beautiful island") for goods including dairy products (Class 29), tea, coffee, cocoa (Class 30), and soft drinks (Class 32) was found to be an indication of origin or sale (IP High Court, November 27, 2013). While standard dictionaries might not explicitly equate "Chura Shima" with Okinawa Prefecture, the court acknowledged its widespread use in contexts like food advertising, local events, news reports, and articles about Okinawan specialty products and tourist sites, leading to a general perception that it referred to Okinawa.

- Multiple Identical Place Names (浅間山 - Asamayama): An interesting issue arose with the trademark "浅間山" (Asamayama, or Mount Asama) for "beer, soft drinks, fruit juices" (Class 32) (IP High Court, June 30, 2014). The applicant argued that since a specialized Japanese mountain encyclopedia lists 31 different mountains named "Asamayama" across Japan, consumers would not be able to identify a specific place of origin, thus the term shouldn't be barred under Article 3(1)(iii). The court disagreed. It reasoned that such a specialized encyclopedia is not something the average person consults, and therefore isn't indicative of general public perception. More common dictionaries, like the Kōjien, primarily refer to the famous Mount Asama located on the border of Nagano and Gunma prefectures. Thus, the general public would likely associate the name with this specific, well-known mountain, making it a recognizable geographical indication.

- Combined Geographical Terms (湘南二宮オリーブ - Shōnan Ninomiya Olive): A trademark "湘南二宮オリーブ" (Shōnan Ninomiya Olive) for various goods across Classes 3, 25, 29, and 30 was deemed to indicate a place of origin or sale (IP High Court, January 28, 2015). "Ninomiya" is a town name that exists in several locations in Japan. However, "Shōnan" is a well-known coastal region south of Tokyo that includes the town of Ninomiya in Kanagawa Prefecture. The court noted the common practice of combining "Shōnan" with more specific local names. This combination led to the conclusion that consumers would perceive it as referring to olive products from Ninomiya in the Shōnan region.

The Exception: Acquired Distinctiveness (Secondary Meaning) - Article 3(2)

It's important to note that even if a mark is primarily a geographical indication, it can still achieve registration under Article 3, Paragraph 2 of the Trademark Law if it has acquired "secondary meaning." This means that through extensive use, consumers have come to recognize the geographical term not just as a place name, but as a distinctive badge of origin for the goods or services of a particular company.

Interestingly, in the GEORGIA case, the commentary mentions that the Tokyo High Court (in parts of its decision not appealed to the Supreme Court) had actually found that for some of the designated goods, the mark "GEORGIA" had acquired such distinctiveness through use by Company X. However, since this specific finding was not a subject of the appeal to the Supreme Court, the Supreme Court did not rule on it.

A later case touched upon both non-applicability of Article 3(1)(iii) and acquired distinctiveness under Article 3(2) (IP High Court, September 13, 2012). This involved the trademark "Kawasaki" (written in a very bold, stylized font similar to Arial Black) for apparel in Class 25 (clothing, belts, hats, etc.). The court found that:

- Due to the distinctive font and supporting survey evidence, the mark "Kawasaki" as presented would not generally make consumers think of the geographical city of Kawasaki in Kanagawa Prefecture when used on apparel. Therefore, it did not fall under Article 3(1)(iii) as a mere geographical indication in this context.

- Furthermore (and perhaps alternatively), the court determined that due to the applicant's long and extensive use of the "Kawasaki" mark in connection with motorcycles and other business activities, the mark had acquired distinctiveness (secondary meaning) even for the designated apparel goods.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in the "GEORGIA" coffee case is a landmark in Japanese trademark jurisprudence. By establishing that the test for a geographical indication under Article 3, Paragraph 1, Item 3 hinges on general consumer or trader perception of likely origin, rather than strict proof of actual production or sale in that location, the Court provided critical guidance. This interpretation balances the public interest in keeping descriptive geographical terms available for common use against the rights of trademark applicants, while also acknowledging the practical realities of trademark examination. The decision continues to be the bedrock for assessing the registrability of geographical names as trademarks in Japan.