The Full Paycheck Rule: Japan's Fukushima Teachers Case and When Employers Can Deduct Overpayments

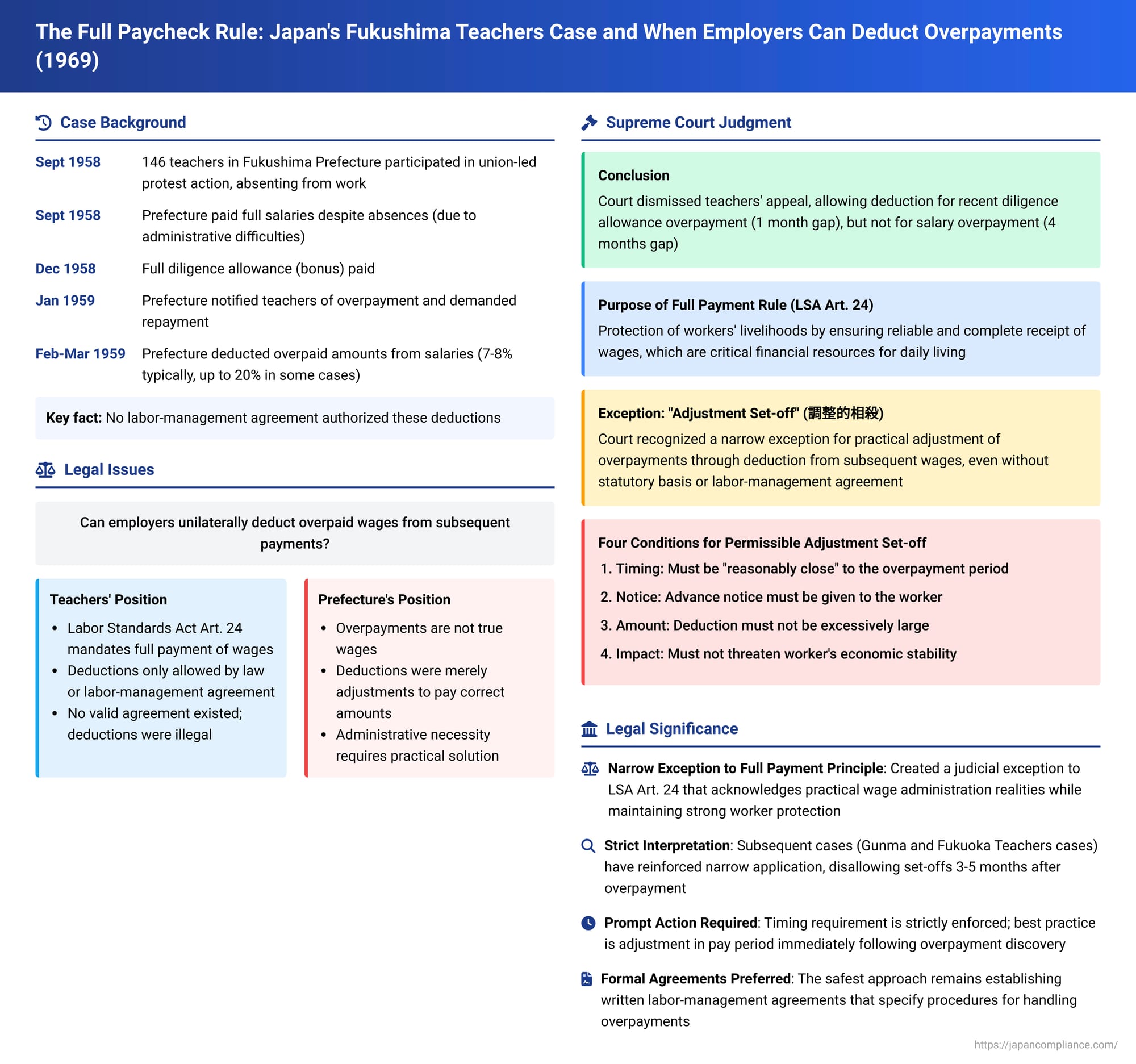

The principle of full payment of wages is a cornerstone of Japanese labor law, enshrined in Article 24 of the Labor Standards Act (LSA). This rule mandates that wages must be paid in full, directly to the worker, in currency, and at least once a month on a fixed date. Exceptions to the "full payment" aspect are narrowly permitted only when stipulated by law (e.g., for taxes or social insurance premiums) or by a written labor-management agreement. The underlying purpose is to ensure that workers, for whom wages are a vital source of livelihood, receive their earnings reliably and without arbitrary deductions, thereby safeguarding their economic stability. However, situations inevitably arise where an employer overpays an employee, perhaps due to administrative errors or because an absence occurs after wages for a period have already been calculated and paid. The Supreme Court of Japan's decision in the Fukushima Prefecture Teachers Union case on December 18, 1969, addressed the complex issue of whether, and under what conditions, an employer can unilaterally recover such overpayments by deducting them from subsequent wage payments.

The Fukushima Teachers' Dispute: Absences, Overpayments, and Delayed Deductions

The plaintiffs, X (comprising 146 public school teachers in F Prefecture), participated in a union-led campaign in September 1958 to protest new work performance evaluations. This action involved them absenting themselves from their duties for a specified period. Due to the large number of participants (several hundred) and the consequent administrative difficulty in processing wage deductions promptly, the defendant, Y (F Prefecture, as the employer), paid X their full salaries and provisional allowances for September 1958. Additionally, in December 1958, Y paid X the full amount of their latter-half diligence allowance (勤勉手当 - kinben teate), a type of bonus paid twice a year.

Approximately four months after the September absences, in January 1959, Y notified the teachers that the payments made for the periods of absence constituted overpayments. Y demanded repayment and stated that if the amounts were not voluntarily returned, they would be deducted from upcoming salary payments. Subsequently, Y proceeded to deduct these overpaid amounts from the teachers' February and/or March 1959 salaries. The amounts deducted generally ranged from 7-8% of an individual's salary, but for some, it exceeded 10%, and in a few instances, reached nearly 20%. It was established that there was no specific statutory provision or labor-management agreement in place that authorized Y to make these deductions from wages.

X sued Y, contending that these deductions violated the full payment principle of LSA Article 24 and sought recovery of the deducted amounts. The Fukushima District Court acknowledged the concept of "adjustment set-off" but held it permissible only if the demand for repayment or notice of deduction was made within a period "adjacent" to when the overpayment occurred. Consequently, it found the deduction for the overpaid salary (where notice was given about four months later) to be illegal. However, it deemed the deduction for the overpaid diligence allowance permissible, as the notice for this was given in the month following the December overpayment. This resulted in an allowed deduction equivalent to about 4% of the salary. Both X and Y appealed parts of this decision. The Sendai High Court, while opining that an "adjustment set-off" effectively means the full correct wage is considered paid at the point of deduction and that deductions up to one-quarter of the wage might be possible, ultimately dismissed both appeals, leaving the District Court's specific outcome for X largely intact. X alone then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's 1969 Ruling: Defining "Adjustment Set-Off"

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby affirming the lower courts' decisions which had, in effect, allowed the set-off for the overpaid diligence allowance but not for the salary overpayment due to the timing differences. In its reasoning, the Supreme Court articulated key principles regarding the full payment rule and the limited permissibility of what it termed "adjustment set-off" (調整的相殺 - chōseiteki sōsai).

- Purpose of LSA Article 24(1) (Full Payment Principle): The Court underscored that the legislative intent behind LSA Article 24(1) is to protect workers' livelihoods. Wages are their critical financial resource for daily living, and ensuring their reliable and complete receipt is paramount for labor policy. Therefore, the provision generally prohibits employers from unilaterally setting off their own claims (debts owed by the employee to the employer) against an employee's wage entitlement.

- The Exception – "Adjustment Set-Off":

The Court recognized, however, that in the practical administration of wage payments, overpayments can unavoidably occur. This might happen when wages for a certain period are paid before that period ends and a reason for wage reduction (like an absence) occurs subsequently, or when such a reason arises so close to the payday that timely adjustment is impossible, or simply due to calculation errors.

In such cases, allowing the employer to adjust or settle these overpayments by deducting them from wages to be paid later is supported by "rational grounds" reflecting the practical realities of wage administration. Moreover, from the employee's perspective, such a deduction to correct an overpayment is different in nature from a set-off against an unrelated debt. Substantively, the employee still ends up receiving the correct total amount of wages due for the work performed.

Considering both the protective purpose of LSA Article 24(1) and these practical realities, the Court concluded that a set-off which serves as a means to pay the correct amount of wages is not prohibited by the full payment principle—even if it doesn't fall under the explicit statutory exceptions (law or labor-management agreement)—provided that its timing, method, and amount are not deemed unjust in relation to the stability of the worker's economic life. - Strict Conditions for Permissible Adjustment Set-Off: The Court laid down specific conditions for such an "adjustment set-off" to be permissible:

- Timing: The set-off must be made at a time "reasonably close" (合理的に接着した時期 - gōriteki ni setchaku shita jiki) to the period of overpayment, so that it retains its character as a wage settlement or adjustment and doesn't lose its practical connection to the original overpayment.

- Advance Notice: The worker should be given advance notice of the deduction.

- Amount: The amount deducted should not be excessively large.

- Overall Impact: Essentially, the deduction must not be such that it threatens the stability of the worker's economic life.

The Supreme Court found that Y's set-off concerning the overpaid diligence allowance (where notice was given in January for a December overpayment, and deduction made in February/March) satisfied these conditions. By implication, it agreed with the lower courts that the set-off for the overpaid September salary (where notice was also given in January, approximately four months later) did not meet the timing requirement.

The Narrow Path of Permissible Deductions

The Fukushima Teachers Union case established the concept of "adjustment set-off" but did so under very strict conditions. Subsequent case law has reinforced the narrowness of this exception.

- Judicial Scrutiny: Courts have consistently interpreted the conditions for adjustment set-off rigorously, emphasizing the primacy of the full payment principle.

- Timing is Critical: The "reasonably close" timing requirement is paramount. An administrative interpretation had previously suggested that settling a prior month's overpayment in the subsequent month was acceptable as a matter of wage calculation. The Supreme Court, in later cases like the Gunma Prefecture Teachers Union case (disallowing a set-off 5 months after overpayment) and the Fukuoka Prefecture Teachers Union case (disallowing a set-off 3 months after), further solidified the view that delays quickly render an adjustment set-off impermissible. Practice strongly favors making adjustments, if at all, in the pay period immediately following the discovery of the overpayment.

- Amount Limitations: There's no fixed percentage for what constitutes an "excessively large" deduction. While the High Court in the Fukushima case mentioned a one-quarter limit (referencing then-existing civil procedure law on wage garnishment limits), actual court practice has been even stricter, with deductions as low as 17-20% of monthly pay being deemed too high in some lower court cases. The standard remains somewhat imprecise.

- Advance Notice: The Fukushima judgment mentioned advance notice as a factor. While its precise procedural necessity and effect haven't been uniformly detailed in every subsequent Supreme Court ruling on the matter, it remains an important consideration for fairness.

- Cause of Overpayment: Some lower court decisions have also taken into account the reason for the overpayment, though the Supreme Court did not explicitly focus on this in the Fukushima decision.

Legal and Academic Perspectives

The Supreme Court's decision to allow adjustment set-offs, even under limited conditions, has generated considerable academic discussion.

- Arguments Against (supporting a strict interpretation of LSA Art. 24): Some scholars argue that any judicially created exception like "adjustment set-off" weakens the vital protection LSA Article 24 provides for workers' economic stability. They contend that employers can unilaterally make these deductions, whereas employees often lack simple or immediate recourse for underpayments. The fact that LSA Article 24 explicitly allows for deductions based on labor-management agreements suggests that this formal route should be used, rather than relying on a less defined judicial exception.

- Arguments For (supporting the Supreme Court's approach): The prevailing view tends to support the Supreme Court's nuanced position, recognizing it as a practical necessity that acknowledges the realities of wage administration. This approach sets reasonable limits ("conditions") to protect employees from undue hardship while allowing for the correction of genuine overpayments.

- Alternative Views: Some scholars categorize overpayment recovery not as a "deduction" or "set-off" in the LSA Article 24 sense, but as a distinct "settlement" or "adjustment" process. However, even under this view, such adjustments might be deemed an abuse of rights if made after a period where the employee reasonably believes no further deduction will occur.

A broader concern highlighted by some is the potential imbalance: employers are afforded this (albeit limited) self-help remedy to recoup overpayments, while employees facing underpayments often have to resort to more complex legal avenues. Data from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has indicated that wage underpayments (e.g., minimum wage violations) are not uncommon, suggesting a wider issue of wage compliance that contrasts with the employer's ability to adjust overpayments.

Practical Implications for Employers

The Fukushima Teachers Union case and the line of jurisprudence it established have clear practical implications for employers in Japan:

- Promptness is Key: If a wage overpayment occurs, it must be identified and addressed very quickly. Any delay in notifying the employee and making the adjustment significantly weakens the employer's ability to unilaterally deduct the amount.

- Amount Matters: Deductions must be modest. Large deductions, even if to recoup a genuine overpayment, are likely to be deemed illegal if they destabilize the employee's finances.

- Clear Communication: Advance notification to the employee about the overpayment and the intended deduction is a crucial factor.

- Prioritize Formal Agreements: The safest and most compliant approach for handling potential wage overpayments is to have a clear, written labor-management agreement in place that specifies the procedure for such adjustments, as permitted by LSA Article 24. This provides a transparent and mutually agreed-upon framework, avoiding reliance on the narrow and strictly interpreted judicial exception of "adjustment set-off." Even general statutory bases for deductions (like local ordinances for public servants) must clearly authorize deduction from subsequent pay periods to be valid for this purpose.

Conclusion

The Fukushima Prefecture Teachers Union case is a significant judgment in Japanese labor law that grappled with the tension between the fundamental principle of full wage payment and the practical need for employers to correct overpayments. While affirming the general prohibition against unilateral employer set-offs against wages, the Supreme Court carved out a narrow exception for "adjustment set-offs" under strict conditions related to timing, amount, notice, and overall impact on the employee's economic stability. Subsequent case law has consistently applied these conditions rigorously, meaning that employers have a very limited window to make such unilateral deductions. For most situations, relying on a clear labor-management agreement remains the most legally sound approach to managing wage overpayments. The ruling underscores the strong legal protection afforded to wages as the critical means of livelihood for workers in Japan.