The Fragile Victim and a Culpable Act: Japan's Supreme Court on Causation in Robbery Resulting in Death

Case Number: 1970 (A) No. 1070

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Date of Decision: June 17, 1971

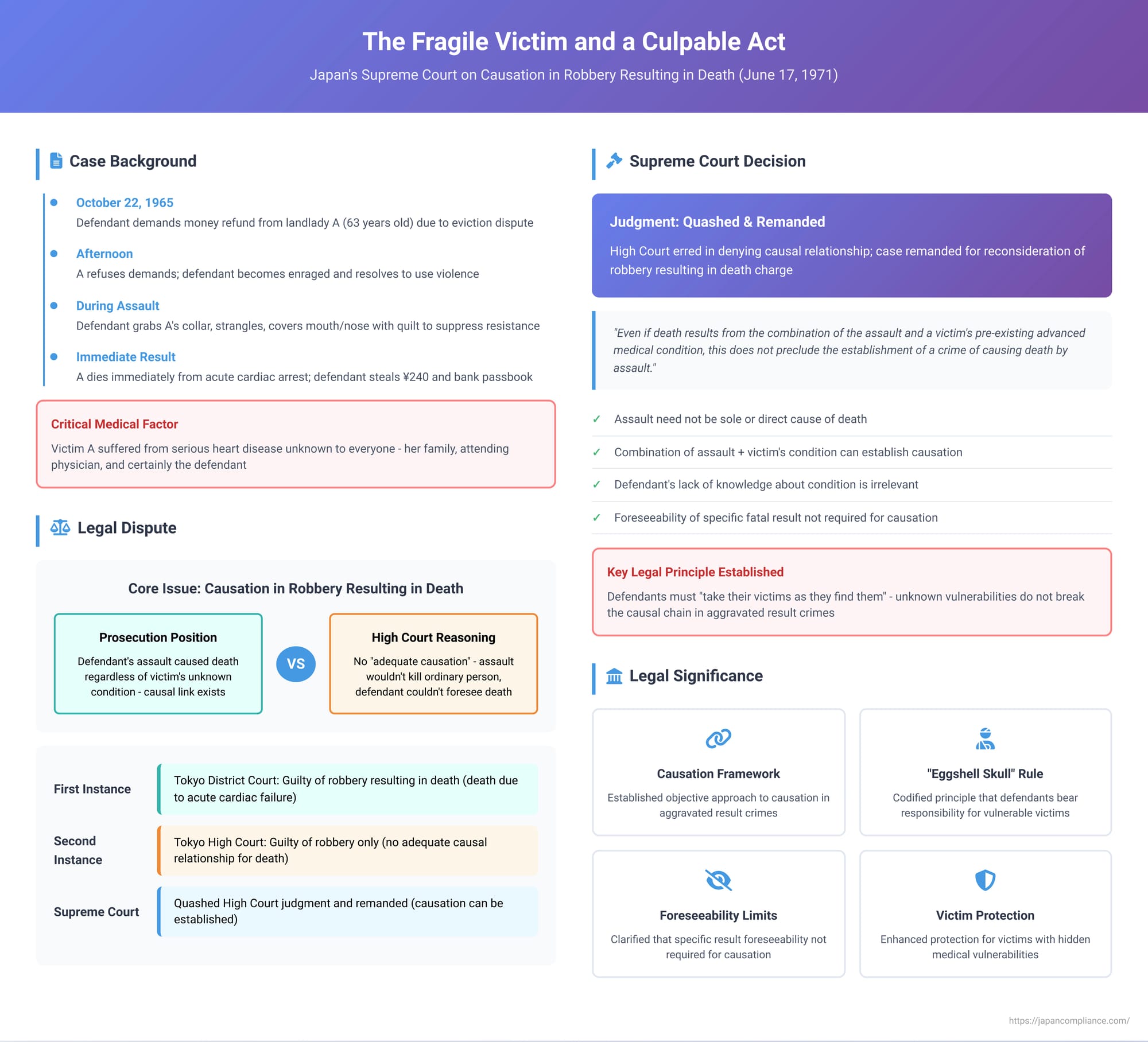

This article explores a landmark Japanese Supreme Court decision that addressed the complex issue of legal causation when a victim's unknown, pre-existing medical condition contributes to their death following a criminal act. The case, involving a robbery that led to the victim's death, delves into whether an assailant can be held liable for the aggravated result (death) even if they were unaware of the victim's unusual susceptibility and the death might not have occurred in an ordinary person.

Facts of the Case

The defendant had been renting a room from A's husband. After disputes arose with A (then 63 years old) regarding his tenancy and demands for him to vacate, the defendant, facing financial difficulties, decided to confront A to demand a refund of rent he believed was owed to him due to the eviction notice.

On October 22, 1965, in the afternoon, the defendant went to A's residence. When his demands for money were strongly refused and A instead demanded pro-rata rent for October, the defendant became enraged. He resolved to use violence to rob A. He grabbed A by the collar, pushed her down onto her back, strangled her with his left hand, covered her mouth with his right hand, and further covered her face with a summer quilt, pressing on her nose and mouth to suppress her resistance. Having thus overpowered A, he stole 240 yen in cash and a bank passbook (with a balance of 98,250 yen) belonging to A's husband from her. The prosecution alleged that this assault caused A's immediate death at the scene due to asphyxiation from the obstruction of her nose and mouth.

Procedural History

The first instance court (Tokyo District Court, decision dated December 19, 1968) found the defendant guilty of robbery resulting in death (gōtō chishi-zai). It determined that the victim's death was due to acute cardiac failure induced by the defendant's assault.

The second instance court (Tokyo High Court, decision dated March 26, 1970) overturned the first instance court's conviction for robbery resulting in death, finding the defendant guilty only of robbery. While the High Court acknowledged that the victim's death from acute cardiac arrest was "triggered by the defendant's assault", it questioned whether a legally cognizable causal link sufficient to impose criminal liability for the death existed.

The High Court adopted what is known as the "eclectic adequate causation theory" (setchū-teki sōtō inga kankei setsu) to assess causation. This theory posits that for causation to be established, the occurrence of the result (death) from the act (assault) must be something that would be considered to normally occur based on common experience. The assessment should be based on:

- General circumstances that an ordinarily prudent person could have known or foreseen at the time of the act.

- Special circumstances that the actor actually knew or foresaw, even if an ordinary person could not have known them.

Applying this framework, the High Court noted:

- The defendant's assault was not of extreme intensity.

- The victim suffered from a serious heart condition, but this condition was unknown even to her attending physician, let alone her family or likely herself. The defendant certainly could not have known about it.

Based on these factors, the High Court concluded that under such specific circumstances, a sufficient "adequate causal relationship" between the defendant's assault and the victim's death could not necessarily be established. It reasoned that while the assault triggered the acute cardiac death, this did not automatically mean there was a causal link for which the defendant should bear criminal responsibility for the death itself.

The Public Prosecutor appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing that the High Court's judgment on causation contradicted established Supreme Court precedents and misinterpreted the relevant articles of the Penal Code.

Supreme Court's Decision and Reasoning

The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's judgment and remanded the case back to the Tokyo High Court for further proceedings.

The Supreme Court began by affirming the High Court's factual finding that the victim A's cause of death was acute cardiac arrest triggered by the defendant's assault as described in the first instance judgment. This finding was deemed well-supported by the evidence, including expert testimony.

However, the Supreme Court then fundamentally disagreed with the High Court's legal interpretation of causation in this context:

The Court stated that "the assault which is the cause of death does not necessarily have to be the sole or direct cause of death." Citing its own precedents, it reiterated the principle that "even if death results from the combination of the assault and a victim's pre-existing advanced medical condition, this does not preclude the establishment of a crime of causing death by assault."

The Supreme Court then directly addressed the High Court's reasoning:

"Therefore, even if, as the original judgment indicated, it is recognized that the defendant's assault in this case would not have resulted in death had it not been for the special circumstance of the victim's serious heart disease, AND even if the defendant did not know of that special circumstance at the time of the act and could not have foreseen the fatal result, as long as it is recognized that the assault, in conjunction with that special circumstance, caused the fatal result, it must be said that there is room to acknowledge a causal relationship between the assault and the fatal result."

The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court, while correctly identifying the victim's cause of death as acute cardiac arrest triggered by the defendant's assault, erred in its interpretation of causation by denying a causal link and thereby negating the charge of robbery resulting in death. The High Court's decision was deemed to contradict established Supreme Court case law.

Legal Analysis and Key Takeaways

This 1971 Supreme Court decision is a cornerstone in Japanese criminal law concerning causation, particularly in the context of "aggravated result crimes" (kekkateki kajūhan) where a basic offense (like robbery) leads to a more serious, unintended consequence (like death).

1. Causation in Japanese Criminal Law: A Brief Overview

The determination of a causal link between an act and a result is fundamental to criminal liability. Japanese law and jurisprudence have grappled with several theories:

- Conditio Sine Qua Non (条件説 - Jōken-setsu): Often referred to as the "but-for" test. An act is a cause if the result would not have occurred without the act. Historically, some Supreme Court precedents were interpreted as aligning with this broad view, particularly for aggravated result crimes. However, this theory was criticized for potentially extending liability too far.

- Adequate Causation Theory (相当因果関係説 - Sōtō Inga Kankei-setsu): This theory seeks to limit causation to cases where the act is not just a "but-for" cause, but also one that, according to common experience, would typically or "adequately" lead to such a result. Variations exist, including:

- Objective adequate causation: Bases foreseeability on what an omniscient observer would know.

- Subjective adequate causation: Bases foreseeability on what the actor actually knew or could have foreseen.

- Eclectic adequate causation (as used by the High Court in this case): Considers what an ordinarily prudent person could foresee, plus any special knowledge the actor possessed.

2. Aggravated Result Crimes (Kekkateki Kajūhan)

Robbery resulting in death (Penal Code Article 240, latter part) is a classic example of an aggravated result crime. These crimes hold an actor liable for a more serious outcome (e.g., death) than originally intended by the basic crime (e.g., robbery), provided there is a causal link. A key debate in Japanese criminal law has been the extent to which foreseeability or negligence regarding the aggravated result is required to establish causation or overall culpability for these offenses. This Supreme Court decision shed significant light on this, particularly concerning unforeseen victim vulnerabilities.

3. The "Eggshell Skull Rule" Principle and Victim's Special Circumstances

This case resonates with the principle often known in common law jurisdictions as the "eggshell skull rule," where the defendant must take their victim as they find them. If a defendant's unlawful act brings about a result (e.g., death) due to the victim's unknown and unusual physical vulnerability, the defendant may still be held liable for that result, even if the same act would not have caused such severe harm to a healthy person.

The Supreme Court's ruling aligns closely with this principle. It held that the defendant's lack of knowledge about A's severe heart condition and inability to foresee her death did not negate the causal link. The crucial factor was that the defendant's felonious assault combined with the victim's pre-existing condition to cause death. This suggests that for aggravated result crimes, the factual chain of events, where the initial unlawful act is a significant contributing factor to the death, can be sufficient for causation, even if an unknown vulnerability plays a critical role.

4. Causation vs. Foreseeability of the Aggravated Result

The Supreme Court's decision implies that for establishing causation in an aggravated result crime like robbery resulting in death, the specific foreseeability of the death itself, or knowledge of the victim's particular vulnerability, is not a prerequisite. The focus is more on the directness of the link between the defendant's criminal act (the robbery and associated violence) and the ensuing death, even if that death was facilitated by an "eggshell" condition.

This distinguishes the causation element from the broader question of culpability or the requirement of negligence for the aggravated result, which has been a subject of extensive academic debate. The PDF commentary notes that this decision adopted a framework akin to the conditio sine qua non theory or an objective adequate causation theory for aggravated result crimes. This approach has been consistently followed in subsequent cases involving pre-existing conditions unknown to the actor.

5. Shift from "Adequate Causation" to "Realization of Risk"

The commentary highlights that while this case used a framework distinct from the High Court's eclectic adequate causation theory, later jurisprudential developments in Japan have often employed the concept of "realization of risk" (kiken no genjitsuka) to analyze causation, especially in cases involving intervening factors. This approach asks whether the specific danger inherent in the defendant's act materialized into the prohibited result.

Under such a "realization of risk" lens, a victim's special condition could be seen as a factor influencing how the inherent danger of the defendant's violent act (e.g., asphyxiation, severe stress) actually materialized as death. The inquiry would focus on whether the death, even if via an unusual mechanism due to the victim's condition, was a realization of a risk created by the defendant's criminal conduct. The Supreme Court's 1971 decision can be seen as an early affirmation of holding defendants accountable for the full consequences of risks they culpably create, even if those consequences are magnified by a victim's unknown frailty.

The academic debate continues on how to best frame causation, particularly when unforeseeable victim vulnerabilities are involved. Some scholars argue for a more objective assessment of the risk created by the act, while others express concern about fairness if actors are held responsible for highly improbable outcomes stemming from conditions they could not possibly have known. Some suggest that if the victim is elderly, certain vulnerabilities might be considered "foreseeable" in a general sense.

Conclusion

The 1971 Supreme Court judgment in this robbery-resulting-in-death case firmly established that an offender can be held causally responsible for a victim's death even if that death was partly due to an unknown, pre-existing medical condition of the victim, and even if the offender could not have foreseen that specific fatal outcome. As long as the defendant's unlawful violent act was a significant cause that, in conjunction with the victim's special circumstances, led to death, a causal link for an aggravated result crime can be affirmed.

This ruling emphasizes a relatively objective approach to causation in such contexts, focusing on the factual chain of events initiated by the defendant's wrongdoing. It underscores the principle that perpetrators of violent crimes may bear responsibility for the full extent of the harm directly flowing from their actions, irrespective of a victim's hidden vulnerabilities. While academic discussions on the precise theoretical underpinnings of causation continue, this decision remains a critical precedent in Japanese criminal law for cases involving victims with special frailties.