The Forger's Photocopier: A 1976 Japanese Supreme Court Case That Redefined "Document"

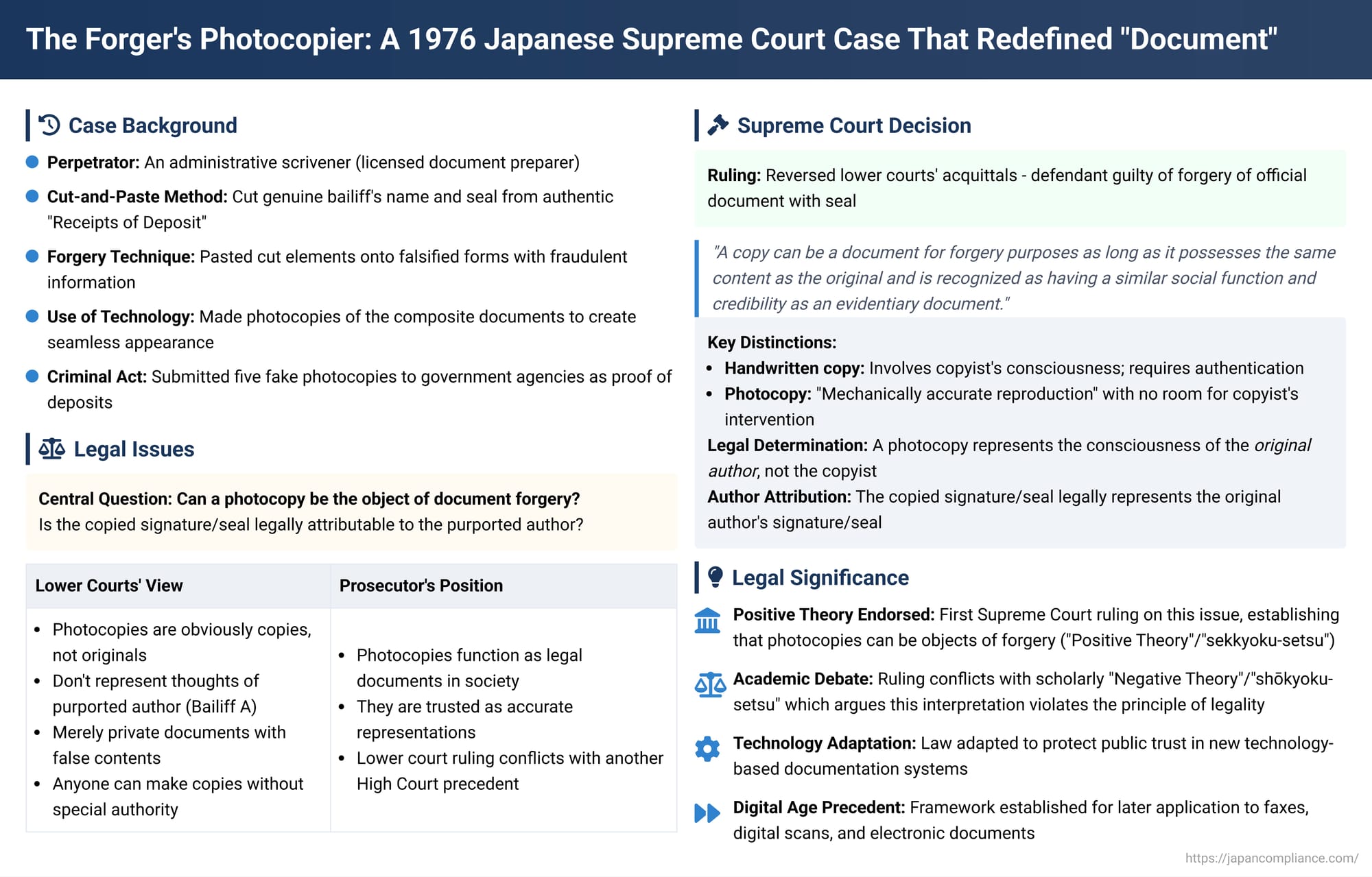

In our modern world of commerce and administration, we rely on copies. We trust that a photocopy or a digital scan is a faithful representation of an original, and we conduct business based on that trust. But what happens when that trust is exploited? If a forger creates a fake document not by hand, but by physically cutting and pasting elements of a real document onto a fraudulent one and then using a photocopier to create a clean, seamless fabrication, is the resulting copy a "forged document" in the eyes of the law? And, more profoundly, who is its legal "author"—the person who operated the machine, or the official whose name and seal are depicted on the page?

These questions, born at the dawn of modern office technology, were at the center of a revolutionary decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 30, 1976. The ruling on the legal status of a photocopy fundamentally reshaped the understanding of document forgery and set a precedent that continues to resonate in the digital age.

The Facts: A Cut-and-Paste Forgery

The defendant was an administrative scrivener, a licensed professional who prepares documents for government filings.

- The Scheme: To prove that security deposits had been made for his clients, he engaged in a sophisticated forgery scheme.

- The Method: He began with genuine "Receipts of Deposit" that had been issued by Bailiff A of the Asahikawa District Legal Affairs Bureau. He physically cut out the sections containing the bailiff's official name and seal from these authentic documents. He then filled out new, blank deposit forms with false information. He pasted the genuine name-and-seal cutouts onto the bottom of his newly created fraudulent documents.

- The Role of Technology: Finally, he used an electronic copier to make photocopies of these composite, pasted-up documents. The resulting photocopies were seamless and appeared to be legitimate copies of authentic, official receipts.

- The Crime: Over several months, he created five such fake photocopies and submitted them to various government agencies, including the Hokkaido Kamikawa Branch Office, as proof that deposits had been made.

The Legal Dilemma: Is a Copy a Document?

The defendant was charged with, among other things, Forgery of an Official Document with a Seal. However, the lower courts acquitted him of this specific charge.

- The Lower Courts' Reasoning: Both the District Court and the High Court ruled that the photocopies were not forged public documents. They reasoned that the items were obviously copies, not originals. As such, they did not directly represent the thoughts or intentions of the person named as the author (Bailiff A). Instead, they were merely private documents with false contents created by the defendant himself. The High Court also noted that since anyone can make a copy, the defendant did not need any special authority from the original author to do so. Disagreeing with this outcome, the prosecutor appealed to the Supreme Court, citing a conflicting High Court precedent.

The Supreme Court's Revolutionary Ruling

The Supreme Court dramatically reversed the lower courts' acquittals and found the defendant guilty of forging an official document with a seal. The Court's detailed reasoning established a new legal framework for understanding documents in an age of mechanical reproduction.

- The Purpose of Forgery Law: The Court began by stating that the purpose of forgery laws is to protect the public's trust in documents as a means of proof and, by extension, to protect the stability of social life.

- Originals vs. Copies: Based on this purpose, the Court found no grounds to limit the objects of forgery to originals only. A copy, it reasoned, can be a document for the purposes of forgery law as long as it "possesses the same content as the original and is recognized as having a similar social function and credibility as a evidentiary document."

- The Magic of the Machine: The Court drew a sharp distinction between a traditional handwritten copy and a photocopy.

- A handwritten copy inevitably involves the consciousness of the copyist and is thus a representation of the copyist's thought ("I have faithfully transcribed X"). It lacks credibility on its own and generally requires separate authentication to function as a legal document.

- A photocopy, however, is a "mechanically accurate reproduction" where there is no room for the copyist's consciousness to intervene. It reproduces not just the text but the handwriting, form, and overall appearance of the original with precision.

- The Author is the Original's Author: Because of this direct, mechanical transmission, the Court found that a photocopy does not represent the consciousness of the person who made the copy. Instead, it directly conveys and possesses the consciousness of the original author. The viewer is led to trust not only in the existence of a corresponding original, but in the contents of that original, including its signature and seal, as if they were viewing the original itself.

- The Final Conclusion: Therefore, a photocopy of a public document can be an object of forgery. In such a case, it should be legally understood as a public document authored by the person named on the purported original (here, Bailiff A). The copied signature and seal are not just images; they legally represent the signature and seal of the original author. The defendant's act of creating a fraudulent document and then photocopying it was an abuse of the bailiff's name and authority, constituting the crime of forgery.

Analysis: A Clash of Theories and the Power of Technology

This 1976 decision was the first time the Supreme Court ruled on the issue, and it decisively endorsed what is known as the "Positive Theory" (sekkyoku-setsu) of photocopy forgery. The ruling has since been solidified by subsequent decisions. However, it remains a point of contention and stands in contrast to the "Negative Theory" (shōkyoku-setsu), which has become the prevailing view among legal scholars in Japan.

- The Negative Theory: Proponents of this view argue that the Supreme Court's ruling is a form of "interpretation by analogy," which is forbidden by the principle of legality (zaikei hōtei shugi—no crime without a statute). They contend that a copy is fundamentally not an original, that the true author is the person who makes the copy, and that a photocopy lacks a direct expression of the purported author's will.

- A Defense of the Court's Ruling: Some scholars defend the Court's conclusion by focusing on a strict definition of a "document." A document requires an expression of thought attributable to an author. A photocopy, through its mechanical accuracy, directly transmits the original author's thoughts. The original author is identifiable through the copied signature and seal. Therefore, the photocopy itself meets the technical definition of a document authored by the original creator, without needing to resort to broader arguments about "social function" or "credibility."

This same logic has since been applied to newer technologies. For instance, a later High Court case, following this precedent, found that a fraudulent document sent by facsimile was also a forged public document.

Conclusion: A Precedent for the Digital Age

The 1976 decision on the forger's photocopier was a seminal moment in the evolution of criminal law. It skillfully adapted the centuries-old crime of forgery to the realities of modern technology. The Supreme Court established the vital principle that a mechanically produced copy, because of its inherent accuracy and the public's well-placed trust in it, can be treated as a legal document in its own right, authored by the person whose credentials it bears. This forward-looking ruling laid the groundwork for how the law would later grapple with faxes, digital scans, and other forms of electronic documentation, affirming that the law's primary goal is to protect the public's trust in information, regardless of the medium on which it is presented.