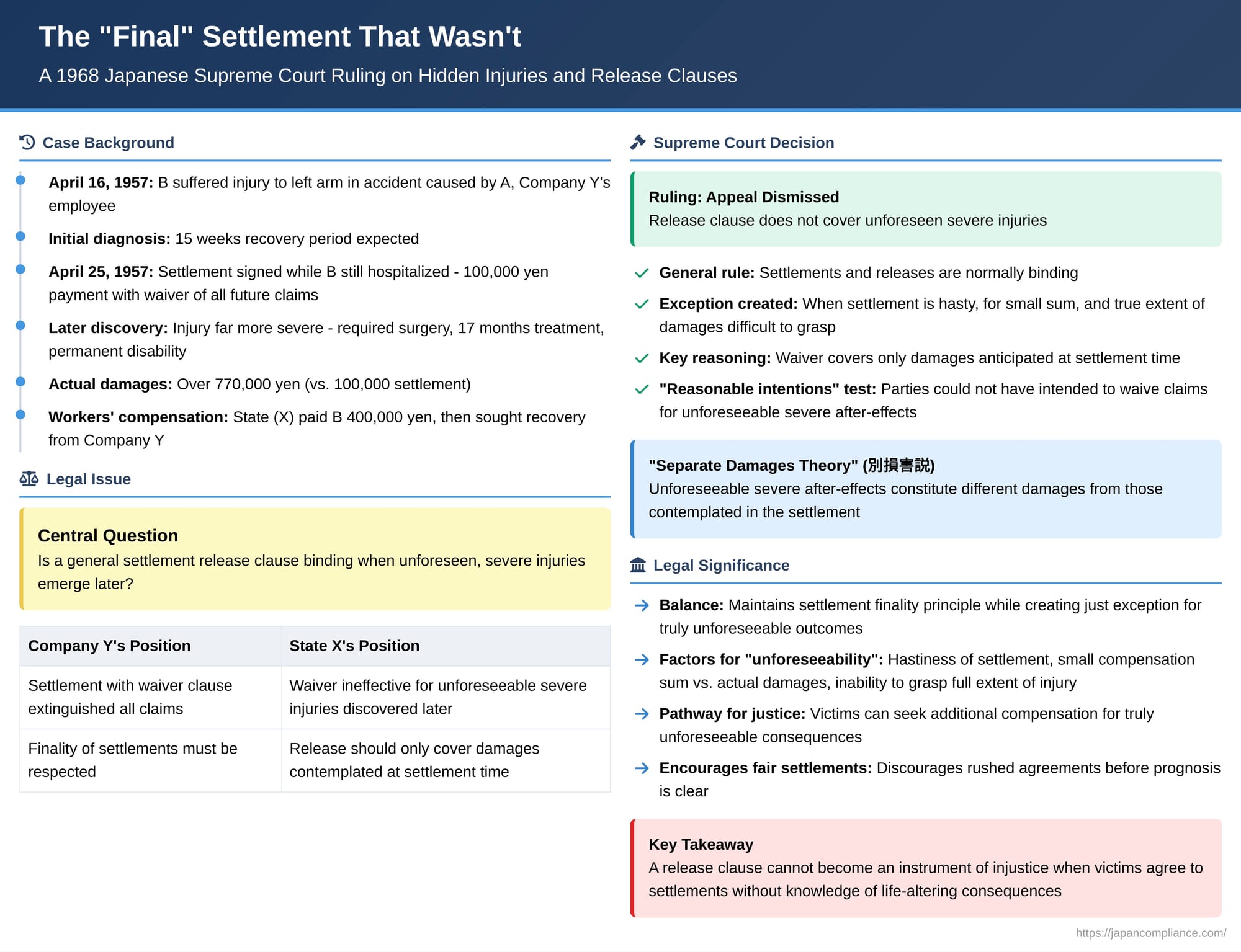

The "Final" Settlement That Wasn't: A 1968 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Hidden Injuries and Release Clauses

Date of Judgment: March 15, 1968

Settlement agreements are a cornerstone of dispute resolution, offering parties a way to achieve finality and move forward. A standard feature of such agreements, particularly in personal injury claims, is a clause where the injured party agrees to release the other party from all further claims in exchange for a sum of money. But what happens when, after the ink has dried, a far more serious injury than initially apparent comes to light? Can a victim seek additional compensation despite having signed a seemingly all-encompassing release? This critical issue was addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a landmark decision dating back to March 15, 1968.

This case, Showa 40 (O) No. 347, grappled with the inherent tension between the need for settlements to be conclusive and the imperative of fairness towards a victim whose true suffering was unknowable when the agreement was made.

The Factual Background: An Injury Profoundly Underestimated

The case arose from an accident on April 16, 1957. A, an employee of Company Y, was driving a truck for business purposes when he struck B, injuring B's left arm. The initial medical diagnosis suggested that B's injuries would fully heal within approximately 15 weeks.

Believing the injury to be relatively minor and that the costs would be covered by motor vehicle damage insurance, B entered into a settlement agreement with Company Y merely nine days after the accident, on April 25, 1957. At the time, B was still hospitalized. The agreement, which was prepared by Company Y without prior negotiation with B, stipulated that B would accept 100,000 yen (the amount payable under the motor vehicle damage insurance policy). In return, B agreed to "waive all future claims for medical expenses, solatium (pain and suffering damages), or any other demands" related to the accident. B agreed to these terms primarily to expedite the receipt of the insurance payment.

However, more than a month after the accident, it became clear that B's injury was far more severe than initially anticipated. B had to undergo further surgery and was ultimately left with a permanent functional impairment of the left forearm joint. The total treatment period stretched to approximately 17 months, and the actual damages B suffered were assessed at over 770,000 yen.

Due to the work-related nature of the injury, X (the State) paid B workers' compensation benefits amounting to roughly 400,000 yen. X then sought to recover this amount from Company Y under the subrogation provisions of the Laborer's Accident Compensation Insurance Law. Company Y defended against this claim by asserting that the settlement agreement between B and Company Y, with its waiver clause, had extinguished all of B's rights to further compensation, thereby nullifying any basis for X's subrogation claim.

The lower court found in favor of X, reasoning that the waiver clause should be interpreted as having a resolutive condition: its effectiveness would cease if a significant, unforeseeable change in B's condition occurred. Company Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Balancing Finality and Fairness

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of March 15, 1968, dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding the lower court's decision to allow for compensation beyond the initial settlement amount, albeit with its own distinct reasoning.

The General Rule: Settlements Are Binding

The Court began by affirming the general principle of settlement finality. It stated: "Generally, in a settlement for damages from an unlawful act, if the victim accepts a certain amount of payment and waives further claims, it is appropriate to interpret this as meaning the victim cannot later claim damages exceeding the settlement amount, even if greater damages existed at the time of settlement or arose subsequently". This acknowledges the fundamental purpose of a settlement – to bring an end to the dispute.

The Crucial Exception: When Unforeseen Damages Emerge

However, the Court then carved out a significant exception to this general rule, tailored to the specific and compelling circumstances of the case. The Court reasoned:

"However, ... when a settlement is made hastily for a small sum of compensation, under circumstances where it is difficult to accurately grasp the full extent of the damages, the claim for damages waived by the victim through the settlement should be construed as relating only to the damages anticipated at the time of the settlement".

Critically, the Court concluded: "To construe this as a waiver of claims for damages arising from unforeseen subsequent surgeries or after-effects, which could not have been anticipated at that time, cannot be said to conform to the parties' reasonable intentions (当事者の合理的意思)".

Applying this to B's situation—where the initial diagnosis was for a 15-week recovery, the settlement was for 100,000 yen, and the injury later turned out to involve permanent disability and damages exceeding 770,000 yen—the Court found the lower court's ultimate conclusion (though based on a different interpretative path of a resolutive condition) to be consistent with this principle.

Interpreting "Reasonable Intentions": The "Separate Damages" Theory

The Supreme Court's approach centered on interpreting the "reasonable intentions" of the parties at the time the settlement was concluded. By focusing on what damages were, or could have been, reasonably contemplated by the parties, the Court effectively adopted what legal commentators have termed the "separate damages theory" (別損害説 - betsu songai setsu).

This theory posits that severe after-effects that were genuinely unforeseeable at the time of the settlement are considered to be different damages from those that were known or anticipated. Consequently, the general waiver clause in the settlement agreement is interpreted as not extending to these separate, unforeseen damages. Its scope is limited to the injuries and consequences that were within the parties' contemplation when they agreed to settle.

This interpretative approach is distinct from other legal constructions that might be considered in such situations:

- It differs from arguing that the entire settlement is voidable due to a fundamental mistake (錯誤 - sakugo) regarding the extent of the injuries. While mistake could be a potential avenue, it might lead to the unraveling of the entire settlement, which may not always be the desired or most equitable outcome, especially if the initial payment was fair for the then-known damages. The Supreme Court's approach allows the original settlement to stand for the damages it was intended to cover.

- It also moves away from the lower court's use of an implied "resolutive condition" (解除条件 - kaijo joken), which some legal scholars found to be an overly artificial construct, imputing an intent to the parties (that the contract dissolves upon a certain event) that they likely did not consciously hold. Instead, the Supreme Court focused on the realistic scope of what was being settled.

Factors Guiding the "Unforeseeable" Determination

The Supreme Court's judgment highlighted several key factual elements that supported the conclusion that B's severe after-effects were beyond the scope of the original settlement:

- Difficulty in Accurately Grasping the Full Extent of Damages: The settlement was made when the true severity of B's condition was not, and perhaps could not have been, known. The initial diagnosis was vastly different from the eventual outcome.

- Hasty Nature of the Settlement: The agreement was concluded very quickly after the accident (within nine days), while B was still hospitalized and likely under duress to secure funds.

- Small Sum of Compensation: The 100,000 yen settlement amount was significantly disproportionate to the more than 770,000 yen in damages that ultimately materialized.

- Unforeseen Nature of Later Complications: The need for subsequent surgeries and the development of a permanent functional impairment were described as "unforeseen" and "unexpected".

Legal analysis suggests that these factors are not necessarily a rigid checklist where all must be present, but rather strong indicators that the later-discovered damages were not part of the parties' "reasonable intentions" when settling.

Different legal perspectives place varying emphasis on these elements:

- One perspective focuses on the objective unforeseeability of the aggravated harm and the substantial disparity between the settlement sum and the actual loss. The core idea here is that the settlement was not based on an informed understanding of the true extent of the injury. The "hastiness" factor might be less critical if, even with more time, the full extent of damages remained latent and ungraspable.

- Another perspective gives more weight to circumstances suggesting a potential exploitation of the victim's vulnerability or disadvantaged position, such as the hastiness of the settlement and the manifest inadequacy of the compensation amount. This view looks at whether the settlement process itself was fair, given the victim's condition and urgent need for funds.

Beyond the factors explicitly mentioned in this judgment, legal practice often considers other relevant circumstances when evaluating such cases. These can include the victim's age, education, business experience, and mental state at the time of settlement, as well as whether they had access to independent medical examinations or legal counsel before signing the release. The presence or absence of a thorough medical diagnosis known to both parties can also be crucial.

Implications of the 1968 Ruling

This Supreme Court decision from 1968 did not open the floodgates for every settled claim to be revisited. The general principle that settlements are final and binding remains intact. However, it carved out a vital and just exception for specific, compelling situations.

Key implications include:

- A Pathway for Justice: It provides a legal basis for victims to seek additional compensation when they suffer grave and genuinely unforeseeable consequences that were not, and could not have been, contemplated at the time of a quick, low-value settlement.

- Burden of Proof: The onus typically falls on the claimant (the victim) to demonstrate that their circumstances fit the exceptional conditions outlined by the Court—that the later-discovered damages were indeed unforeseeable and that the original settlement was made under conditions where the true scope of injury was not appreciated.

- Preservation of Original Settlement (for known damages): The "separate damages" theory allows the initial settlement to remain valid for the damages that were known and intended to be covered at the time. The additional claim is specifically for the "new" or "separate" damages that were unforeseeable.

- Encouraging Fairer Settlements: The existence of this exception may also encourage those potentially liable to ensure that settlements, especially with vulnerable individuals or where prognoses are uncertain, are not unduly rushed and are based on the best available information, perhaps even prompting them to consider clauses that explicitly address the possibility of unknown future complications if they wish for true finality.

Conclusion: A Lasting Legacy of Fairness

The Supreme Court's March 15, 1968, decision remains a significant precedent in Japanese tort law. It adeptly balances the important public interest in the finality of settlements with the fundamental principle of ensuring just compensation for those who suffer harm due to unlawful acts. By focusing on the "reasonable intentions of the parties" and allowing for claims related to truly unforeseeable severe after-effects, the Court established a framework that prevents waiver clauses from becoming instruments of injustice when victims, through no fault of their own, agree to settlements without knowledge of the full, life-altering consequences of their injuries. This ruling continues to inform the resolution of complex post-settlement disputes where the passage of time reveals a reality far graver than anyone initially perceived.