The Fake Lawyer with a Real Name: Japan's Landmark Forgery Case

What's in a name? In the realm of criminal law, this question can be surprisingly complex. Imagine you share the exact same name as a licensed and respected professional, like a doctor or a lawyer. If you were to create a document—say, an invoice for professional services—using your own, real name but adding the title and credentials of your professional doppelgänger, have you committed the crime of document forgery? Or can you claim innocence on the grounds that you simply used your own name?

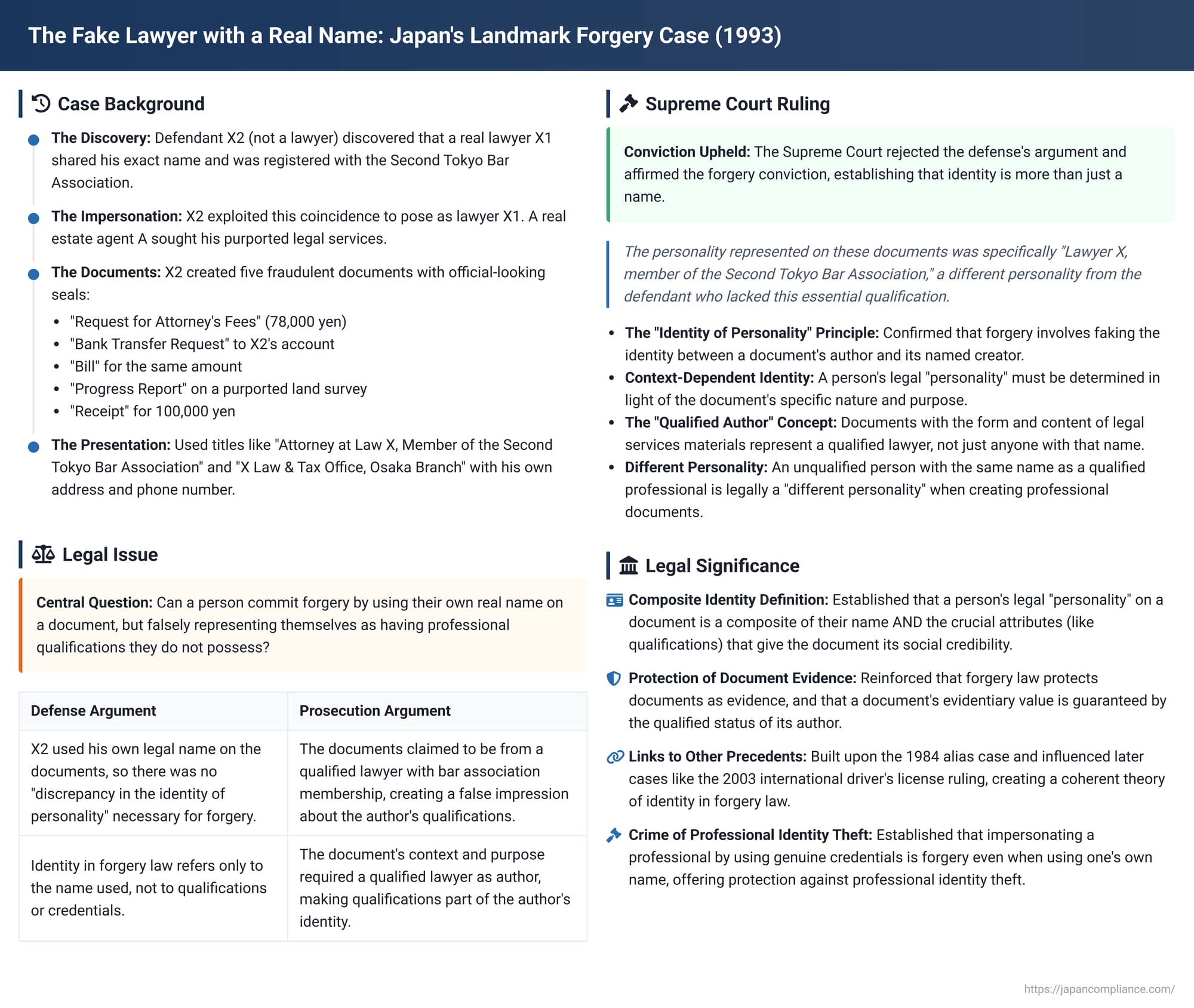

This fascinating and highly specific question of identity, qualification, and criminal intent was at the heart of an October 5, 1993, decision by the Supreme Court of Japan. The case, involving a man who impersonated a lawyer with whom he shared a name, pushed the boundaries of forgery law and clarified how the courts determine a person's legal "personality" on a document.

The Facts: The Unqualified Man Named X

The case centered on the defendant, whom we will call X2, who was not a lawyer.

- A Fortunate Coincidence: X2 discovered that there was a real, practicing lawyer, X1, who not only had the exact same name but was also a registered member of the prestigious Second Tokyo Bar Association.

- The Impersonation Scheme: X2 exploited this coincidence to impersonate the lawyer X1. A real estate agent, A, believing X2 was a lawyer, sought his services. To obtain payment, X2 created a series of documents.

- The Forged Documents: Over a short period, X2 created five fraudulent private documents, including:

- A "Request for Attorney's Fees" billing 78,000 yen for a land survey.

- A "Bank Transfer Request" instructing payment to X2's own bank account.

- A formal "Bill" for the same amount.

- A "Progress Report" on the purported land survey.

- A "Receipt" for 100,000 yen for the land survey fee.

- The Appearance of Authenticity: On these documents, X2 used titles such as "Attorney at Law X, Member of the Second Tokyo Bar Association" and "X Law & Tax Office, Osaka Branch." He used official-looking seals, including a square seal designed to resemble the real lawyer's and a round seal engraved with the words "Official Seal of Attorney at Law X." Some of the documents also included X2's own address and phone number.

The Legal Defense: "I Used My Own Name"

The core of the defense's argument was simple and powerful: X2 had used his own, real name on the documents. The crime of forgery hinges on a discrepancy between the author of a document and the person named in it (the meigi-nin). Since the author (X2) and the person named on the document (X) were, in name, the same, the defense argued there could be no "discrepancy in the identity of personality" and thus no forgery.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Identity is More Than a Name

The Supreme Court rejected this defense and upheld the forgery conviction. The Court's reasoning was a masterclass in legal nuance, establishing that in the context of official and professional documents, identity is comprised of more than just a name.

- The Principle of "Identity of Personality": The Court began by reaffirming the principle it had established in a 1984 case: the essence of forgery is faking the "identity of personality" between a document's author and its named creator.

- Context is Everything: However, the Court immediately declared that this identity cannot be determined in a vacuum. It stated that even though the defendant used his own name, the legal analysis must consider the document's specific nature.

- The "Qualified Author": The Court found that because the documents were created with the "form and content" of documents prepared by a qualified lawyer in connection with legal services, the "named person" on these documents was not just any individual named X. The personality represented was specifically "Lawyer X, member of the Second Tokyo Bar Association."

- A "Different Personality": This qualified legal professional, the Court declared, is a "different personality" from the defendant, X2, who lacked the essential attribute of being a lawyer.

- The Forgery: By creating documents that purported to be from this "qualified" personality, the defendant had created a "discrepancy in the identity of personality" and was therefore guilty of forgery.

Analysis: Forging an Identity, Not Just a Document

This decision solidifies a critical principle in Japanese forgery law: a person's legal "personality" on a document is a composite of their name and the crucial attributes that give that document its social credibility and meaning.

- The "Social Credibility" Foundation: The public's trust in a document like a legal invoice is not based on the name alone, but on the belief that it originates from a licensed, qualified professional. The "lawyer" qualification is the very foundation of the document's credibility. Therefore, the law identifies the document's author as the person possessing that essential qualification. This logic was later made more explicit in a 2003 Supreme Court case concerning fake international driver's licenses, where the Court stated that the authority to issue the license was what gave the document its social credibility, and thus the author was the "organization with the authority to issue the license."

- The Role of the Document as Evidence: A deeper theory supporting the Court's decision frames forgery as a crime against a document's function as evidence. The evidentiary value of a professional document is guaranteed by the fact that a qualified individual stands behind its contents. When an unqualified person creates such a document, it lacks this guarantee and has no true evidentiary value. This act harms the public's trust in this entire class of evidence.

- Addressing the Critiques: This line of reasoning also helps to answer the critiques of the decision. Some might argue that since the recipient of the documents knew he was dealing with X2, there was no deception about identity for him. However, the Court considers that such documents could circulate to third parties who would be deceived. Others might argue that since X2's own contact information was on some documents, he could be held responsible, obviating the need for a forgery charge. But this misses the point: the law protects the public's trust in the document as authentic evidence from a qualified professional, a trust that is broken regardless of whether the forger can be tracked down later.

Conclusion

The 1993 "fake lawyer" case is a vital lesson in the sophistication of forgery law. It teaches that identity is not a simple matter of matching names on a page. The ruling establishes that when a document's authority and credibility are intrinsically tied to the professional qualifications of its purported author, the legal "personality" of that author includes those qualifications. Using one's own name is no defense against a forgery charge if it is done to impersonate a qualified professional and create a document whose power stems entirely from a status one does not possess. In this sense, the crime is not just forging a document, but forging an entire professional identity.