The Expanding Circle: Supreme Court Broadens Resident Standing in Urban Development Lawsuits

Judgment Date: December 7, 2005, Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

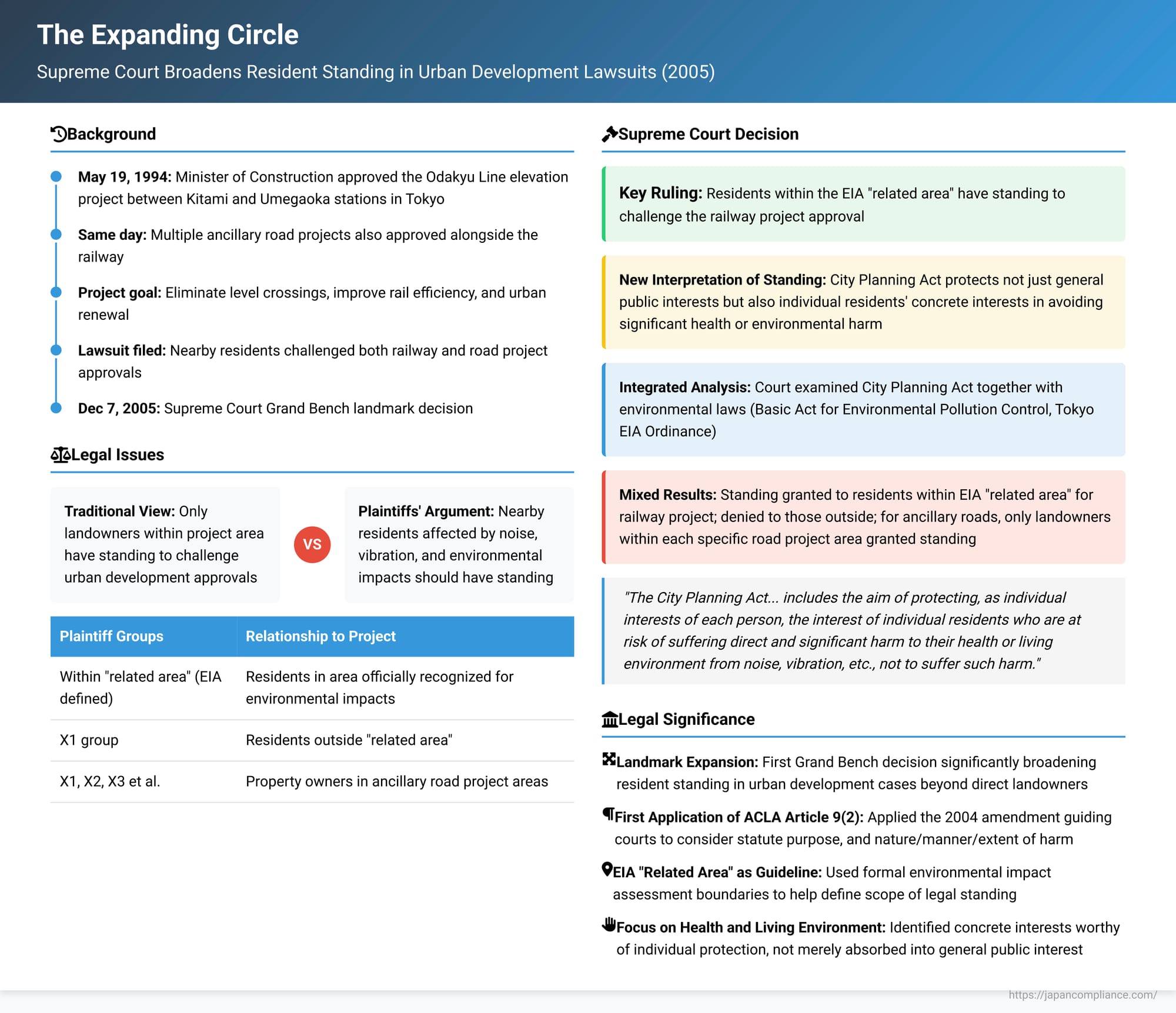

Urban development projects, particularly large-scale infrastructure works like railway elevations, often promise significant public benefits such as improved transportation and urban renewal. However, these projects can also impose considerable burdens on residents living near the construction and operation sites, including noise, vibration, and impacts on their living environment. A crucial question in Japanese administrative law has been the extent to which these affected residents have the legal standing to challenge the governmental approvals for such projects. A landmark 2005 Grand Bench decision by the Supreme Court, concerning the Odakyu Line continuous grade separation project in Tokyo, significantly broadened the understanding of plaintiff standing for residents in these types of cases.

The Odakyu Line Project: Facts of the Dispute

The case involved two main sets of urban development project approvals (事業認可 - jigyō ninka) granted by the then-Minister of Construction to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government under Article 59, Paragraph 2 of the City Planning Act:

- The Railway Project Approval: Granted on May 19, 1994, this approved the project to elevate a section of the Odakyu Odawara Line, a major commuter railway, between Kitami and Umegaoka stations in Tokyo. This was part of a larger continuous grade separation project aimed at eliminating level crossings and improving rail efficiency.

- The Ancillary Road Project Approvals: Also granted on May 19, 1994, these approved several related projects for the construction of ancillary roads alongside parts of the elevated railway section. A primary stated purpose of these roads was to mitigate the impact on sunlight for properties along the railway line, as an environmental consideration for the grade separation.

X et al. (the plaintiffs) were residents living in areas surrounding the railway project. Some of them (X1 and X2) also owned property or had rights within the land designated for one of the ancillary road projects (Ancillary Road No. 9), and others (X3 et al.) owned land within the area for another ancillary road project (Ancillary Road No. 10). However, a significant number of the plaintiffs did not own property directly within either the railway project area or the ancillary road project areas but resided in the vicinity.

Under the Tokyo Metropolitan Environmental Impact Assessment Ordinance, a "related area" had been defined for the railway project, signifying the zone where significant environmental impacts were anticipated. Some plaintiffs resided within this EIA-defined "related area," while others (specifically, those in X1 group of the judgment) resided outside it.

X et al. filed a lawsuit against Y (the Kanto Regional Development Bureau Chief, as the successor to the Minister of Construction's administrative functions) seeking the revocation of both the Railway Project Approval and the various Ancillary Road Project Approvals. They argued that these approvals were illegal.

The Tokyo District Court (First Instance) partially accepted the residents' claims but dismissed the suit for some plaintiffs for lack of standing. The Tokyo High Court (Second Instance) took a more restrictive view, ultimately finding that most, if not all, of the residents' claims should be dismissed, largely on the grounds that they lacked the necessary legal standing, particularly those not directly owning land within the project areas. X et al. appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Expanding Standing for Nearby Residents

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court, in its judgment on December 7, 2005, significantly altered the landscape for plaintiff standing in such cases. It ruled that certain groups of residents living near the railway project did have standing to challenge the Railway Project Approval, even if they did not own land directly within the project site itself.

I. Reaffirming and Elaborating the "Legally Protected Interest" Standard

The Court began by restating its established general test for plaintiff standing from Article 9, Paragraph 1 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA). It affirmed that "a person who has 'legal interest' ... to seek the revocation of the said disposition" is one "whose rights or legally protected interests are infringed, or are inevitably threatened with infringement, by the said disposition". It further explained that if the administrative statute underlying the disposition "is construed as including an aim to protect, as individual interests of each person to whom they belong, the concrete interests of an unspecified number of persons, beyond merely absorbing and dissolving them into the general public interest, then such interests also qualify as 'legally protected interests' herein".

Crucially, the Court then explicitly referenced Article 9, Paragraph 2 of the ACLA (which had been introduced in a 2004 amendment, though the principles were evolving in case law prior to that). This provision guides courts in determining "legally protected interest" by considering:

- The purpose and objective of the empowering statute and any related statutes.

- The content and nature of the interest that would be harmed if the disposition were made in violation of the empowering statute.

- The manner and extent to which that interest would be harmed.

II. Interpreting the City Planning Act in Light of Broader Environmental Laws

The Supreme Court then analyzed the City Planning Act, under which the project approvals were granted, in conjunction with broader environmental protection laws:

- City Planning Act's Aims: The City Planning Act aims to promote the sound development and orderly improvement of cities, contributing to balanced national development and the enhancement of public welfare. One of its fundamental principles is to secure a healthy and cultural urban life. It requires that urban plans conform to any existing pollution control plans and that urban facilities are designed to maintain a good urban environment. The Act also includes provisions for public participation, such as public hearings and the submission of opinions by residents, in the urban planning process.

- Consideration of Anti-Pollution Laws: The Court then referred to the (now repealed but relevant at the time) Basic Act for Environmental Pollution Control (公害対策基本法 - Kōgai Taisaku Kihon Hō). This Act aimed to protect citizens' health and conserve the living environment by establishing comprehensive measures against pollution like noise and vibration. It mandated the creation of pollution control plans for areas with significant existing or potential pollution. The Court noted that the City Planning Act required urban plans to conform to such pollution control plans.

- Tokyo's Environmental Impact Assessment Ordinance: The Court also took into account the Tokyo Metropolitan Environmental Impact Assessment Ordinance, which required prior assessment of environmental impacts for projects like railway construction and aimed to ensure proper consideration for pollution prevention to secure residents' healthy and comfortable lives.

- Combined Purpose: Considering these laws together, the Supreme Court concluded that the provisions of the City Planning Act concerning urban development project approvals "are to be construed as having the purpose and objective of also preventing harm to the health or living environment of residents in the surrounding area due to noise, vibration, etc., accompanying the project, thereby securing a healthy and cultural urban life and preserving a good living environment".

III. Impact on Residents and the Nature of Harm

The Court then focused on the nature of the harm suffered by residents near such projects:

- If an urban development project is approved based on an illegal urban plan, residents in a certain range of the surrounding area will be directly affected by noise, vibration, and other impacts. The severity of this impact generally increases with proximity to the project site.

- If residents continue to live in such an area and are repeatedly and continuously exposed to these harms, "the damage can extend to significant harm to the health or living environment of these residents".

- The Court found that the provisions of the City Planning Act, in light of their purposes, "are to be construed as seeking to protect the concrete interest of residents in the surrounding area of the project site not to suffer such significant harm to their health or living environment due to an illegal project".

- Crucially, the Court stated that "in light of the content, nature, degree, etc., of the said harm, this concrete interest is one that is difficult to be considered as absorbed and dissolved into the general public interest".

IV. Individual Interests Protected

Based on this, the Supreme Court concluded:

"The City Planning Act... includes the aim of protecting, as individual interests of each person, the interest of individual residents who are at risk of suffering direct and significant harm to their health or living environment from noise, vibration, etc., not to suffer such harm".

V. Application to the Plaintiffs (X et al.)

Applying this refined understanding to the specific plaintiffs:

- The Court noted that X et al. (excluding the X1 group) resided within the "related area" defined under the Tokyo Environmental Impact Assessment Ordinance for the Railway Project. The EIA ordinance defines this "related area" as the area where the project is likely to have a significant environmental impact.

- Considering this, the Court found that these plaintiffs residing within the EIA-defined related area "are recognized as persons who are at risk of suffering direct and significant harm to their health or living environment due to noise, vibration, etc., if the said Railway Project is implemented. Therefore, they have standing to seek the revocation of the said Railway Project Approval".

- For the X1 group, who lived outside this EIA-defined "related area," the Court found no grounds to conclude they faced such a risk and thus denied them standing for the Railway Project Approval.

- Regarding the Ancillary Road Project Approvals, standing was affirmed only for those plaintiffs who owned property within the specific land areas designated for those particular road projects (X1, X2 for Ancillary Road No. 9; X3 et al. for Ancillary Road No. 10). Other residents were denied standing to challenge the ancillary road approvals, as the Court did not find they faced a direct risk of significant harm to health or living environment from those specific road projects themselves, which were primarily intended to mitigate sunlight impacts. Four justices dissented on this latter point concerning the ancillary roads, arguing that these roads were an integral part of the overall railway project and that residents with standing for the main railway project should also have standing for these related environmental mitigation measures.

Significance and Analysis

The 2005 Odakyu Line judgment is a landmark for several reasons:

Broadened Standing for Third-Party Residents

The most significant aspect is its departure from previous, more restrictive Supreme Court precedents (like a 1999 ruling) that had generally limited standing in urban development project approval cases to those owning property directly within the project site. This decision explicitly recognized that residents in the surrounding area could also have legally protected interests and thus standing, provided they are at risk of "direct and significant harm to health or living environment" from the project.

Explicit Use of ACLA Article 9, Paragraph 2

This was the first Supreme Court decision to explicitly cite and apply the then-newly amended Article 9, Paragraph 2 of the ACLA. This provision directs courts to consider the purpose of the empowering statute and related laws, and the nature, manner, and extent of the harm, when determining "legally protected interest." The Court's detailed analysis of the City Planning Act in conjunction with the Basic Act for Environmental Pollution Control and the Tokyo EIA Ordinance demonstrates the application of this expanded interpretive framework. This signaled a move towards a more flexible and context-sensitive approach to standing.

Focus on "Health or Living Environment"

The Court identified "not suffering significant harm to health or living environment" as the specific, individually protected interest for nearby residents. This provided a more concrete basis for standing in environmental public nuisance cases compared to relying on more abstract rights.

The Role of Environmental Impact Assessment Areas

The Court's reliance on the "related area" defined under the Tokyo EIA Ordinance as a key factor in determining the geographical scope of standing for the railway project was a novel and practical approach. It suggests that official environmental impact assessment boundaries can serve as an important, though not necessarily conclusive, indicator of who is likely to suffer direct and significant harm. However, the judgment also left room for individuals outside such formally defined areas to potentially establish standing if they could prove the requisite level of risk.

Unresolved Questions and Future Directions

While a significant step forward, the judgment also left some questions. The PDF commentary notes that the precise definition and threshold for "significant harm to health or living environment" remain subject to interpretation in future cases. The Court's somewhat differentiated approach to standing for the main railway project versus the ancillary road projects (for those not owning land in the road project areas) also illustrates the fact-specific nature of these inquiries.

The dissenting opinion regarding the ancillary roads highlighted the ongoing debate about how integrally related components of a larger development project should be treated for standing purposes, particularly when some components are designed as mitigation measures for others.

Conclusion

The 2005 Supreme Court decision in the Odakyu Line continuous grade separation project case marked a significant evolution in Japanese administrative law concerning plaintiff standing. By explicitly incorporating the amended ACLA Article 9, Paragraph 2 and by looking to related environmental laws to interpret the protective scope of the City Planning Act, the Court broadened the potential for residents living near large urban development projects to challenge their approvals.

The judgment recognized that the interest in being free from significant harm to one's health or living environment due to noise, vibration, and other impacts from such projects can constitute a "legally protected interest" sufficient to grant standing. While the precise boundaries of this standing will continue to be defined in future cases, the Odakyu Line decision represents a clear move towards providing more effective judicial recourse for citizens affected by major public works and development projects, emphasizing a more substantive and context-sensitive approach to determining who has the right to be heard in court.