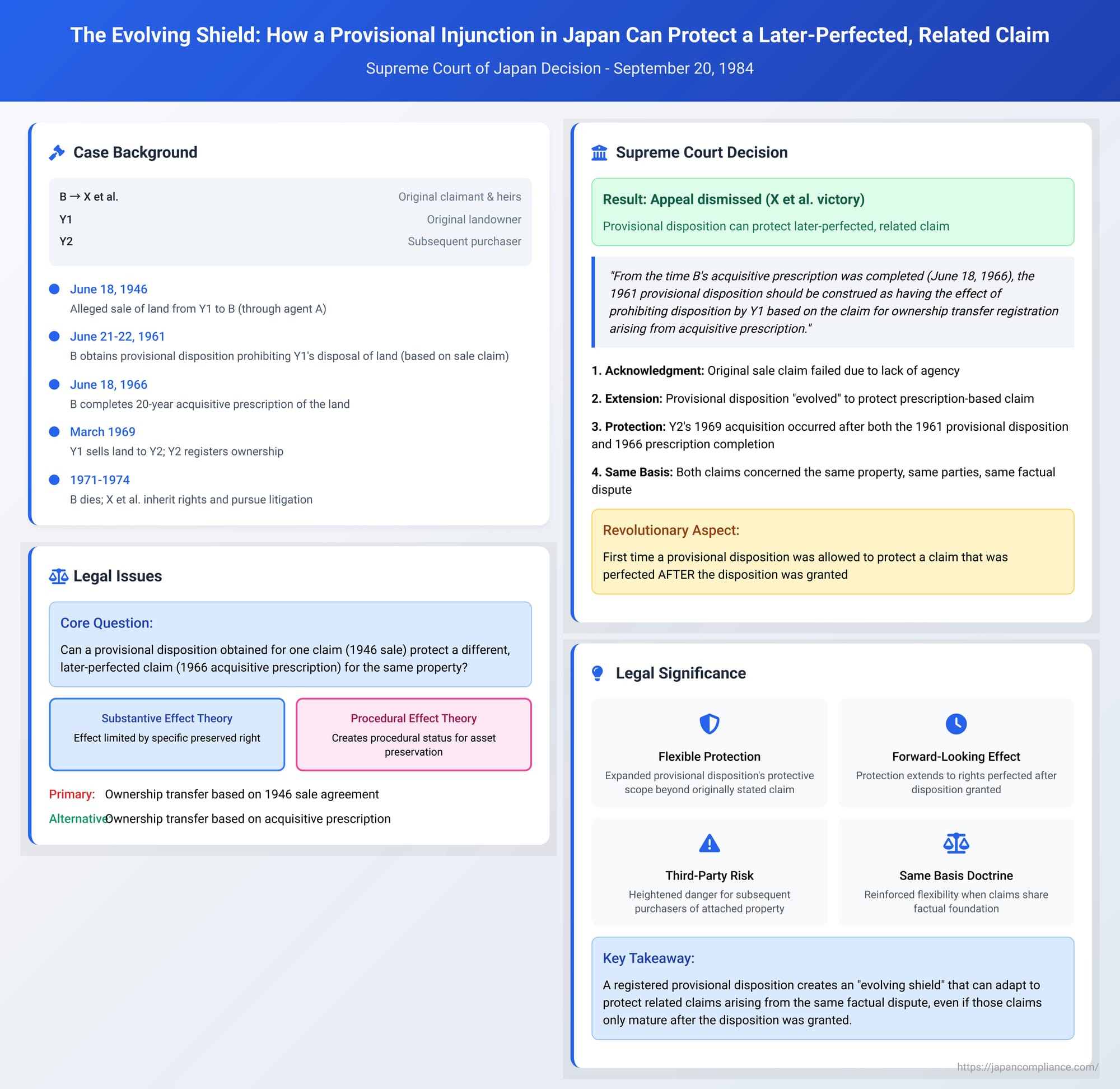

The Evolving Shield: How a Provisional Injunction in Japan Can Protect a Later-Perfected, Related Claim

Date of Supreme Court Decision: September 20, 1984

Provisional dispositions, particularly those prohibiting the disposition of property (処分禁止の仮処分 - shobun kinshi no karishobun), are vital tools in Japanese civil procedure. They aim to "freeze" an asset, preventing its sale or encumbrance, while the underlying rights to that asset are being litigated in a main lawsuit. A fascinating and complex question arises when the legal basis for the claimant's right to the property evolves or is re-characterized during the course of lengthy legal proceedings. Can a provisional disposition, initially obtained to secure a claim based on one legal ground (e.g., a sale agreement), continue to protect the claimant if that ground fails but another related ground (e.g., acquisitive prescription) is successfully established, especially if the second ground only fully matured after the provisional disposition was issued? A 1984 Supreme Court of Japan decision (Showa 53 (O) No. 1119) delved deep into this issue, offering a remarkably flexible interpretation of the provisional disposition's protective scope.

The Decades-Long Property Dispute: A Timeline

The case involved a parcel of land ("Honken Tochi") and a protracted dispute over its ownership, spanning several decades:

- The Purported Sale (1946): On June 18, 1946, an individual named A, allegedly acting as an agent for Y1 (the original registered owner of the land), purportedly sold the land to B. However, no ownership transfer registration was made at this time. B took possession of the land.

- Provisional Disposition Based on Sale (1961): Fifteen years later, on June 21, 1961, B, to secure his claim for ownership transfer registration arising from the 1946 sale agreement, obtained a provisional disposition from the court. This order prohibited Y1 from disposing of the land. This provisional disposition was duly registered on June 22, 1961, providing public notice of B's asserted claim and the restriction on Y1's ability to deal with the property.

- Completion of Acquisitive Prescription (1966): While B's claim based on the 1946 sale was pending or developing, B continued to possess the land. The High Court later found that B, having possessed the land with the intent to own it, peacefully and openly, completed the requirements for acquisitive prescription (時効取得 - jikō shutoku) of 20 years on or around June 18, 1966. This meant that, as of this date, B had potentially acquired ownership through prescription, independent of the validity of the 1946 sale.

- Sale to a Third Party, Y2 (1969): In February 1969, Y1 (the original owner) sold the same land to Y2. Y2 subsequently completed a conditional ownership transfer provisional registration (jōken-tsuki shoyūken iten karitōki) on March 3, 1969, followed by a full ownership transfer registration on March 25, 1969. At this point, Y2 appeared on the public register as the owner.

- Succession and Litigation: B passed away on December 3, 1971, and his rights were inherited by X et al. (the plaintiffs in the main lawsuit). In March 1974, the 1961 provisional disposition (which B had obtained) was formally affirmed in a judgment resulting from a "provisional disposition objection" (仮処分異議 - karishobun igi) proceeding between X et al. and Y1.

X et al.'s Main Lawsuit:

X et al. (as B's heirs) filed a lawsuit against both Y1 (the original owner) and Y2 (the subsequent purchaser). Their claims were structured as follows:

- Primary Claim: Based on the original 1946 sale agreement. They sought an order compelling Y1 to complete the ownership transfer registration based on that sale. Against Y2, they sought the cancellation of Y2's 1969 registrations, arguing that Y2's acquisition was made in violation of the 1961 provisional disposition (which prohibited Y1 from disposing of the property) and therefore Y2 could not assert its ownership against them.

- Alternative Claim: If the 1946 sale was found to be invalid, X et al. argued that B had acquired ownership through acquisitive prescription, completed in 1966. On this alternative ground, they sought an ownership transfer registration from Y1 and, similarly, the cancellation of Y2's registrations, again contending that the 1961 provisional disposition protected B's (and thus X et al.'s) claim against Y2's later acquisition.

The Lower Courts' Divergent Paths on the Sale vs. Prescription

- The court of first instance found the 1946 sale (conducted by the alleged agent A) to be valid and ruled in favor of X et al. on their primary claim.

- The High Court, however, took a different view:

- It rejected the primary claim, finding that A lacked the proper authority to act as Y1's agent in the 1946 sale. Thus, the sale agreement itself was invalid.

- Critically, the High Court upheld X et al.'s alternative claim based on acquisitive prescription. It found that B had indeed possessed the land for the requisite 20 years, completing the prescription period around June 18, 1966.

- The High Court then reasoned that because B had obtained and registered the provisional disposition against Y1 in 1961 (prohibiting Y1 from disposing of the land), and because B's acquisitive prescription was completed in 1966, X et al. (as B's heirs) could assert the protective effect of this 1961 provisional disposition against Y2. Since Y2 had purchased the land from Y1 and registered title in 1969—after the provisional disposition was in effect and after B's prescriptive rights had matured—Y2 could not assert its ownership against X et al.

Y1 and Y2 appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the High Court had erred. Their main contention was that the 1961 provisional disposition was explicitly obtained to preserve a claim based on the 1946 sale agreement. It should not, they argued, be allowed to protect a different claim based on acquisitive prescription, especially a claim that was only perfected (in 1966) after the provisional disposition itself had been granted (in 1961).

The Supreme Court's Affirmation: Expanding the Provisional Disposition's Protective Ambit

The Supreme Court, in its decision of September 20, 1984, dismissed the appeal by Y1 and Y2, thereby upholding the High Court's conclusion in favor of X et al. This was a significant ruling on the "objective scope" (効力の客観的範囲 - kōryoku no kyakkanteki han'i) or potential "diversion" (流用 - ryūyō) of a provisional disposition's protective effect.

The Court's Key Holding:

- The Supreme Court first acknowledged that, in the relationship between X et al. (B's heirs) and Y2 (the subsequent purchaser), the 1961 provisional disposition did not have the effect of prohibiting Y1's disposition of the land based on the originally stated preserved right—namely, the claim for ownership transfer arising from the 1946 sale. This was because the High Court had found the 1946 sale itself to be invalid due to lack of agency.

- However, and this was the crucial part of the ruling, the Supreme Court held that from the time B's acquisitive prescription was completed (around June 18, 1966), the very same 1961 provisional disposition should be construed as having the effect of prohibiting disposition by Y1 based on the claim for ownership transfer registration arising from acquisitive prescription as its (now operative) preserved right.

- Therefore, X et al. could validly assert the protective effect of the 1961 provisional disposition against Y2. Since Y2 had purchased the land from Y1 and registered its title in 1969—which was after the 1961 provisional disposition was registered and after B's acquisitive prescription claim had matured in 1966 (making the provisional disposition now protective of that prescriptive claim)—Y2 could not assert its ownership rights (derived from Y1) against X et al.

In essence, the Supreme Court allowed the protective shield of the 1961 provisional disposition, initially raised for a sale-based claim, to transform and extend its protection to the later-perfected, factually related claim based on acquisitive prescription.

Key Legal Concepts and Underlying Reasoning

This decision touches upon several complex legal concepts:

- Identity of the Subject Matter in Dispute (訴訟物 - soshōbutsu): Under the "old theory of the subject matter of dispute" (kyū soshōbutsu riron), which has traditionally been followed by Japanese courts, a claim for ownership transfer based on a sale agreement (a contractual right) and a claim for ownership transfer based on acquisitive prescription (often viewed as giving rise to a real right – bukken-teki kenri) are generally considered distinct causes of action because the essential facts (shuyō jijitsu) required to establish each claim differ. The Supreme Court's handling of primary and alternative claims in this case implicitly reflects this distinction.

- Nature of a Disposition Prohibition Provisional Order: Such an order, when registered, has the effect of rendering subsequent dispositions of the property (e.g., a sale to Y2) relatively null and void vis-à-vis the provisional disposition creditor (X et al.). That is, the subsequent purchaser (Y2) cannot assert their acquired rights against the creditor (X et al.) if the creditor ultimately succeeds in establishing their preserved right (as per current CPRA Art. 58(1)).

- Theories on the Scope of Provisional Dispositions:

- "Substantive Effect Theory" (実体的効力説 - jittaiteki kōryoku setsu): This is the prevailing view in Japan. It holds that the effect of a provisional disposition is derived from, and thus limited by, the specific "preserved right" it aims to protect. It generally cannot be used to protect entirely unrelated rights.

- "Procedural Effect Theory" (訴訟的効力説 - soshōteki kōryoku setsu): An alternative view suggests that the provisional disposition primarily creates a procedural status to preserve assets for future execution, with less emphasis on the precise nature of the preserved right. Allowing a "diversion" of the provisional order's effect would be easier under this theory.

Given the dominance of the "substantive effect theory," allowing the 1961 provisional disposition to protect a different (though related) right like acquisitive prescription required careful justification by the Supreme Court.

- The "Same Basis of Claim" (請求の基礎の同一性 - seikyū no kiso no dōitsusei) Doctrine: This doctrine is crucial for understanding the Supreme Court's reasoning. It allows for a degree of flexibility when comparing the "preserved right" stated in a provisional disposition application and the claim ultimately pursued or established in the main lawsuit. If both claims arise from substantially the same underlying factual matrix or dispute, the provisional order can maintain its efficacy.

- Rationale for Flexibility: Provisional remedy applications are often made under urgent conditions, where precise legal formulation of the claim might be difficult. If the core factual dispute remains consistent, the protective purpose of the initial provisional order can still be served without undue prejudice to the debtor. Amendments to pleadings are often possible in the main lawsuit or in objection proceedings to align the preserved right with the evolving understanding of the claim.

- This 1984 Supreme Court decision implicitly relies on this concept, even if it doesn't use the exact terminology as explicitly as some later decisions (e.g., the Heisei 24.2.23 decision, also discussed in these blog posts).

- Novelty: Diversion to a Right Perfected After the Provisional Disposition was Granted: What makes this 1984 decision particularly noteworthy is that the claim based on acquisitive prescription was only perfected around June 1966, a full five years after the provisional disposition (obtained for the sale claim) was granted and registered in 1961. Most prior discussions about the "same basis of claim" implicitly assumed that both the initially stated preserved right and the alternative related right existed in some form (even if imperfectly pleaded) at the time the provisional disposition was sought.

- The Supreme Court's willingness to allow the 1961 provisional disposition to "reach forward" and protect this later-perfected prescriptive claim is a significant extension of its protective ambit. Legal commentary suggests this is justifiable on the grounds that the provisional disposition creditor (B, and later X et al.) could have, in theory, applied to amend the "preserved right" in their provisional disposition once the acquisitive prescription was completed, for instance, during the provisional disposition objection proceedings. If such an amendment would have been permissible to reflect the new legal basis for their claim to the same property against the same original party, then the original provisional disposition should be allowed to have a continuing protective effect for that new, factually related right against third parties (like Y2) who acquired their interests after the original provisional disposition was registered.

Concluding Thoughts

The September 20, 1984, Supreme Court decision is a significant illustration of the flexible and purposive interpretation sometimes applied to the effects of provisional dispositions in Japan. It established that a provisional disposition prohibiting the disposal of property, initially obtained to secure a claim based on a sale agreement, can indeed extend its protective effect to cover a subsequent claim for ownership transfer based on acquisitive prescription for the same property, by the same claimant against the same original owner, from the moment that acquisitive prescription is completed.

This ruling demonstrates the judiciary's inclination to uphold the protective function of a registered provisional disposition when the claimant's underlying assertion of a right to the specific property remains consistent, even if the precise legal foundation for that assertion evolves or is re-characterized during prolonged litigation. It serves as a strong caution to third parties: transacting in property that is subject to a registered provisional disposition carries considerable risk, as the protective scope of that interim order might be interpreted more broadly than its initially stated "preserved right," particularly if other related rights based on the same core factual circumstances mature or are successfully established by the provisional disposition creditor. The decision underscores the enduring power of a registered provisional measure to "freeze" the status of property against subsequent adverse claims.