EU Data Act Compliance for US Firms with Japanese Links: Key Risks & Strategic Steps

TL;DR

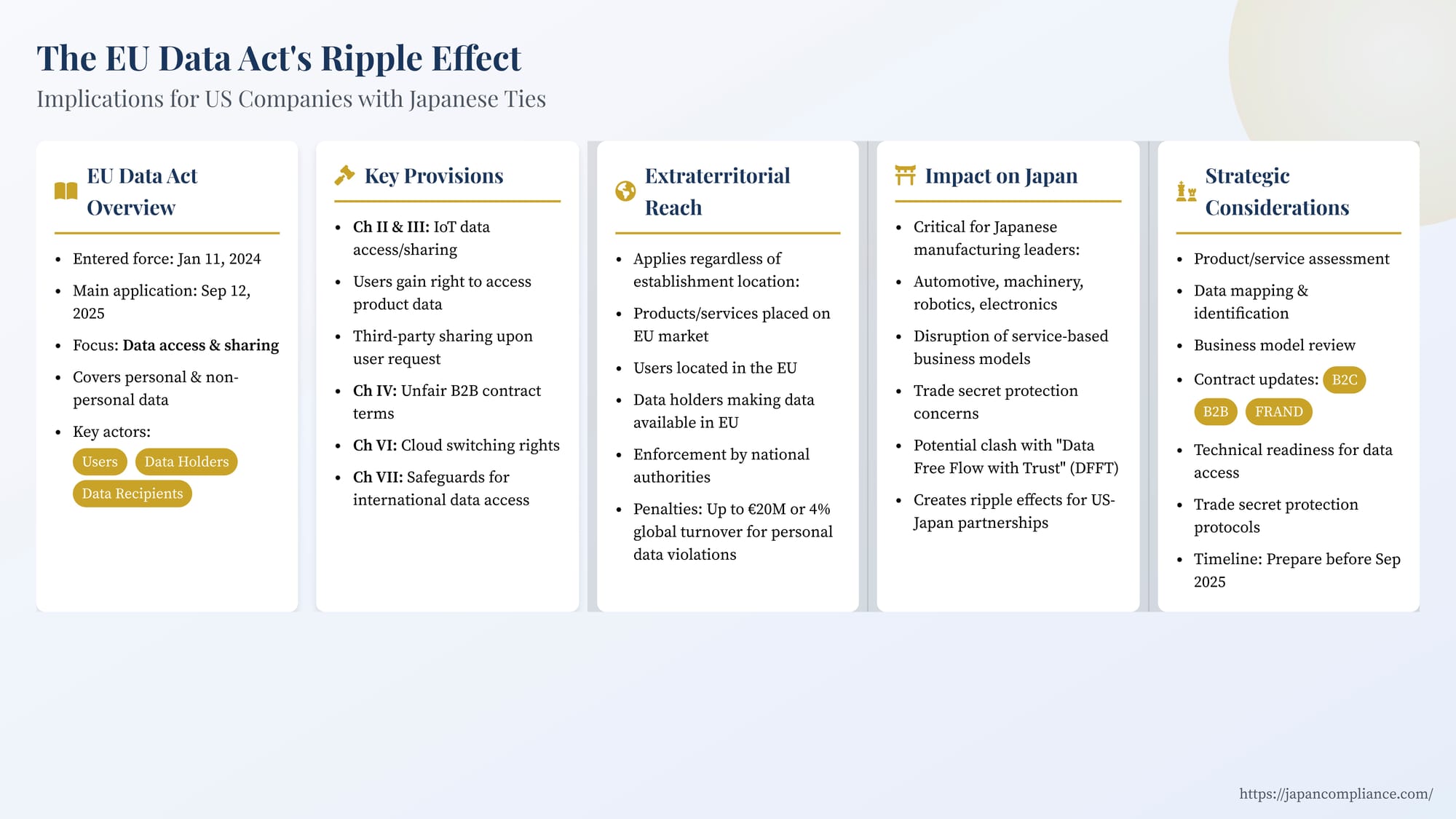

- The EU Data Act, in force since Jan 2024 and fully applicable from Sep 2025, mandates broad data-sharing rules for IoT and non-personal data.

- Japanese manufacturers in automotive, machinery and electronics will be heavily affected, creating knock-on compliance duties and market shifts for US partners.

- US companies should map IoT data flows, renegotiate contracts, and prepare for cloud-switching and third-country-access safeguards to avoid penalties up to 4 % global turnover.

Table of Contents

- What Is the EU Data Act? Core Objectives and Scope

- Key Provisions Impacting Business

- Extraterritorial Reach and Enforcement

- Why the Data Act Matters to Japan (Ripple Effects)

- Strategic Considerations for Businesses

- Conclusion

The European Union continues its ambitious project to shape the digital economy through comprehensive regulation. Following landmarks like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Digital Markets Act (DMA), and the Digital Services Act (DSA), the EU Data Act represents the next significant piece of legislation, shifting focus from data protection to data access, sharing, and utilization. Having entered into force on January 11, 2024, with its main provisions set to apply from September 12, 2025, the Data Act promises to reshape how data, particularly data generated by connected devices (IoT), is controlled and used within and beyond the EU.

While an EU regulation, its impact extends globally. For US companies, understanding the Data Act is crucial not only for direct compliance if operating in the EU but also due to its significant implications for key trading partners like Japan, whose industries are deeply intertwined with the data ecosystems the Act seeks to regulate.

What is the EU Data Act? Core Objectives and Scope

The primary goal of the Data Act is to unlock the economic and societal value of data by establishing harmonized rules on who can access and use data generated within the EU across all economic sectors. It aims to ensure fairness in the digital environment, stimulate a competitive data market, open opportunities for data-driven innovation, and make data more accessible for the benefit of businesses, consumers, and the public sector.

Key characteristics of the Act include:

- Broad Scope: Unlike GDPR's focus on personal data, the Data Act covers both personal and non-personal data.

- IoT Focus: A significant portion of the Act specifically targets data generated by the use of "connected products" (physical items that collect/generate data about their use or environment and can communicate it, e.g., smart appliances, industrial machinery, connected vehicles) and "related services" (digital services, including software, integrated with a connected product essential for its function, e.g., an app controlling a smart thermostat).

- Shift from Ownership to Access: The Act deliberately moves away from defining data "ownership." Instead, it focuses on establishing rights and obligations related to data access and sharing for various actors:

- Users: Individuals or businesses who own, rent, or lease a connected product or receive a related service.

- Data Holders: Entities (often the manufacturer or service provider) having the technical ability and legal right/obligation (including contractual) to make data available.

- Data Recipients: Third parties (excluding the user) to whom data is made available upon the user's request.

- Data Processing Service Providers: Cloud and edge service providers.

Key Provisions Impacting Business

While the Data Act is extensive, several chapters have particularly significant implications for businesses:

Chapters II & III: Access and Sharing of IoT Data (B2C and B2B)

These are arguably the most transformative sections.

- User Access Rights: Users gain the right to access the data generated by their use of connected products and related services. Data holders must make this data available, often directly by design (a requirement for new products placed on the market from September 12, 2026) or upon request without undue delay and generally free of charge to the user.

- Third-Party Sharing Rights: Users can request data holders to share this data directly with third-party data recipients of their choice (excluding designated gatekeepers under the DMA).

- Impact on Business Models: This right to share data with third parties could significantly disrupt business models reliant on exclusive access to device-generated data. For example, manufacturers offering proprietary maintenance or optimization services based on data from their equipment may now face competition from independent service providers who can request data access via the user. This could impact sectors ranging from industrial machinery and automotive to consumer electronics and smart home devices.

- Compensation (FRAND): While users access data for free, data holders can request compensation from third-party data recipients (except SMEs, non-profits, or research organizations) based on Fair, Reasonable, and Non-Discriminatory (FRAND) terms, plus a reasonable margin (unless providing to SMEs/non-profits). Compensation should primarily reflect the costs of making the data available.

- Trade Secret Protection: This is a critical balancing act. While data holders must generally grant access, they are not required to disclose trade secrets. However, they must implement robust technical and organizational measures agreed upon with the user/recipient (like confidentiality agreements) to protect any sensitive information within the shared data. Only in exceptional circumstances, where disclosure poses a high risk of serious economic damage despite safeguards, can access to specific data points identified as trade secrets be refused. This requires data holders to proactively identify and manage their trade secrets within generated data streams.

Chapter IV: Unfair Contractual Terms in B2B Data Sharing

This chapter aims to protect businesses, particularly Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs), from unfair contractual terms related to data access and use that are unilaterally imposed by a party with significantly stronger bargaining power. It provides a blacklist of terms considered automatically unfair (e.g., excluding liability for gross negligence) and a grey list of terms presumed unfair (e.g., terms limiting the SME's right to terminate unreasonably).

Chapter VI: Switching Cloud and Edge Services

To reduce vendor lock-in and promote competition, this chapter imposes obligations on providers of data processing services (cloud and edge computing). It aims to make it easier for customers (both business and consumer) to switch providers by regulating contracts, setting standards for interoperability, and phasing out switching charges.

Chapter VII: Safeguards Against Unlawful International Data Access

This chapter addresses concerns about third-country government access to non-personal data held within the EU. It requires data processing service providers to take "all reasonable technical, legal and organisational measures" to prevent international governmental access or transfer of non-personal data where such access/transfer would conflict with EU law or the national law of the relevant Member State. Providers can only comply with a third-country decision requiring access/transfer under specific conditions, such as it being based on an international agreement (like an MLAT) or if stringent checks on legality and proportionality are met, minimizing the data transferred. This provision has generated significant discussion regarding potential conflicts with laws like the US CLOUD Act.

Extraterritorial Reach and Enforcement

Like GDPR, the Data Act has significant extraterritorial scope. It applies to:

- Manufacturers of connected products and providers of related services placed on the EU market, regardless of where the manufacturer/provider is established.

- Users of such products/services located in the EU.

- Data holders (wherever established) making data available to recipients within the EU.

- Data recipients (wherever established) to whom data is made available.

- Providers of data processing services offering services to customers in the EU.

- Public sector bodies requesting data from holders under Chapter V.

Enforcement will be handled by designated national competent authorities in each EU Member State. Non-compliance can lead to substantial penalties. While Member States will set specific penalty rules, infringements of Chapters II, III, and V related to personal data can be fined by data protection authorities under the GDPR framework (up to €20 million or 4% of global annual turnover, whichever is higher). Other infringements will be subject to penalties defined by Member States, which must be "effective, proportionate, and dissuasive."

Why the Data Act Matters to Japan (and its Ripple Effect)

The Data Act holds particular significance for Japan due to several factors:

- Strong Manufacturing & IoT Sector: Japan is a global leader in manufacturing industries like automotive, industrial machinery, robotics, and consumer electronics – sectors heavily reliant on connected products and the data they generate. The Act's provisions on IoT data access and sharing directly impact the business models and data governance strategies of these major Japanese corporations.

- Impact on Service Models: Many Japanese manufacturers have built significant after-sales service businesses based on proprietary access to data from their products. The Data Act's mandate for third-party data sharing could force a fundamental rethink of these models, potentially opening the market to independent service providers.

- Trade Secret Concerns: Japanese industry has expressed concerns, including through organizations like the Japan Intellectual Property Association (JIPA), about the potential risks to valuable trade secrets and know-how posed by the mandatory data access provisions. While the Act includes safeguards, the burden of identifying and protecting trade secrets, especially under potential pressure for broad access, is a key challenge. Japan's legal tradition potentially viewing raw data itself as having competitive value may clash with the EU's perspective reflected in the Act.

- Data Strategy Alignment: Japan promotes its own vision for data governance, often encapsulated in the "Data Free Flow with Trust" (DFFT) concept. The Data Act's prescriptive approach presents both challenges and opportunities for aligning international data flows and governance frameworks.

These direct impacts on major Japanese industries inevitably create ripple effects for US companies that:

- Partner with or Compete against Japanese Firms: US companies collaborating with Japanese manufacturers (e.g., in automotive supply chains) may need to navigate data sharing agreements impacted by the Act. Competitors may find new opportunities if data previously locked within Japanese ecosystems becomes accessible.

- Have Japanese Subsidiaries/Operations: US parent companies will need to ensure their Japanese subsidiaries comply with the Data Act if their products or services fall within its scope regarding the EU market.

- Operate in Global Supply Chains: Data generated by a component manufactured by a Japanese company subject to the Act, incorporated into a product sold by a US company in the EU, could potentially trigger Data Act obligations.

- Are Cloud/Data Service Providers: US cloud giants offering services in the EU must comply with Chapter VI (switching/interoperability) and Chapter VII (government access safeguards) requirements.

- Face Potential Global Standards: The "Brussels Effect" could see elements of the Data Act influencing regulations or industry standards in other parts of the world, indirectly affecting US companies' global operations.

- Navigate Legal Conflicts: The restrictions in Chapter VII regarding non-personal data access by foreign governments could create direct compliance conflicts for US companies subject to both EU data rules and US laws like the CLOUD Act, which permits US authorities to compel access to data held by US providers globally.

Strategic Considerations for Businesses

Given the Data Act's broad scope and the looming September 2025 application date, proactive preparation is essential for potentially affected US and Japanese companies:

- Product/Service Assessment: Determine which connected products or related services offered (directly or indirectly) in the EU market fall under the Act's scope.

- Data Mapping: Understand what product and related service data is generated, collected, processed, and held. Identify potential trade secrets within these data streams.

- Review Business Models: Assess the impact of mandatory data access and sharing on existing revenue streams, particularly after-sales services. Identify potential new opportunities created by access to data from others.

- Contract Review: Update B2C terms to include required pre-contractual transparency information (Art 3). Review B2B data sharing agreements for compliance with unfair terms provisions (Ch IV). Prepare template agreements for data sharing with third parties, incorporating FRAND principles and trade secret protections.

- Technical Readiness: Evaluate technical capabilities to provide users with data access (including direct access by design for new products) and share data securely with third parties upon request. Implement robust measures to protect trade secrets during sharing.

- Cloud/Data Processing Services: If providing or using such services targeting the EU, prepare for enhanced switching/interoperability requirements and implement the necessary technical, legal, and organizational safeguards against unlawful third-country government access (Ch VII).

- Develop Internal Procedures: Establish clear processes for handling user data access and third-party sharing requests, including verifying requests, identifying trade secrets, negotiating safeguards, and calculating FRAND compensation where applicable.

Conclusion

The EU Data Act is a landmark regulation poised to significantly alter the landscape of data access, sharing, and utilization, particularly for data generated by the Internet of Things. Its influence will extend far beyond the EU's borders, creating substantial compliance obligations and strategic challenges for companies in technologically advanced economies like Japan. For US businesses with direct operations in the EU or significant ties to Japanese partners and suppliers, understanding the Data Act's ripple effects is not just prudent but necessary. Proactive assessment and strategic planning are essential to navigate the complexities, mitigate risks, and potentially capitalize on the new data-driven opportunities this far-reaching legislation will create when it comes into full application in September 2025.

- Cyber-Incident Response in Japan: APPI Compliance & Cybersecurity Basics Explained

- Ransomware in Japan: APPI Duties, Sanctions Risk & Practical Response Guide

- AI Training Data and Copyright in Japan: Understanding Article 30-4 Exceptions

- Cabinet Office “Data Free Flow with Trust” (DFFT) Initiative Overview