The Enduring Value of Brand Image: A Deep Dive into a 1998 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Sales Method Restrictions

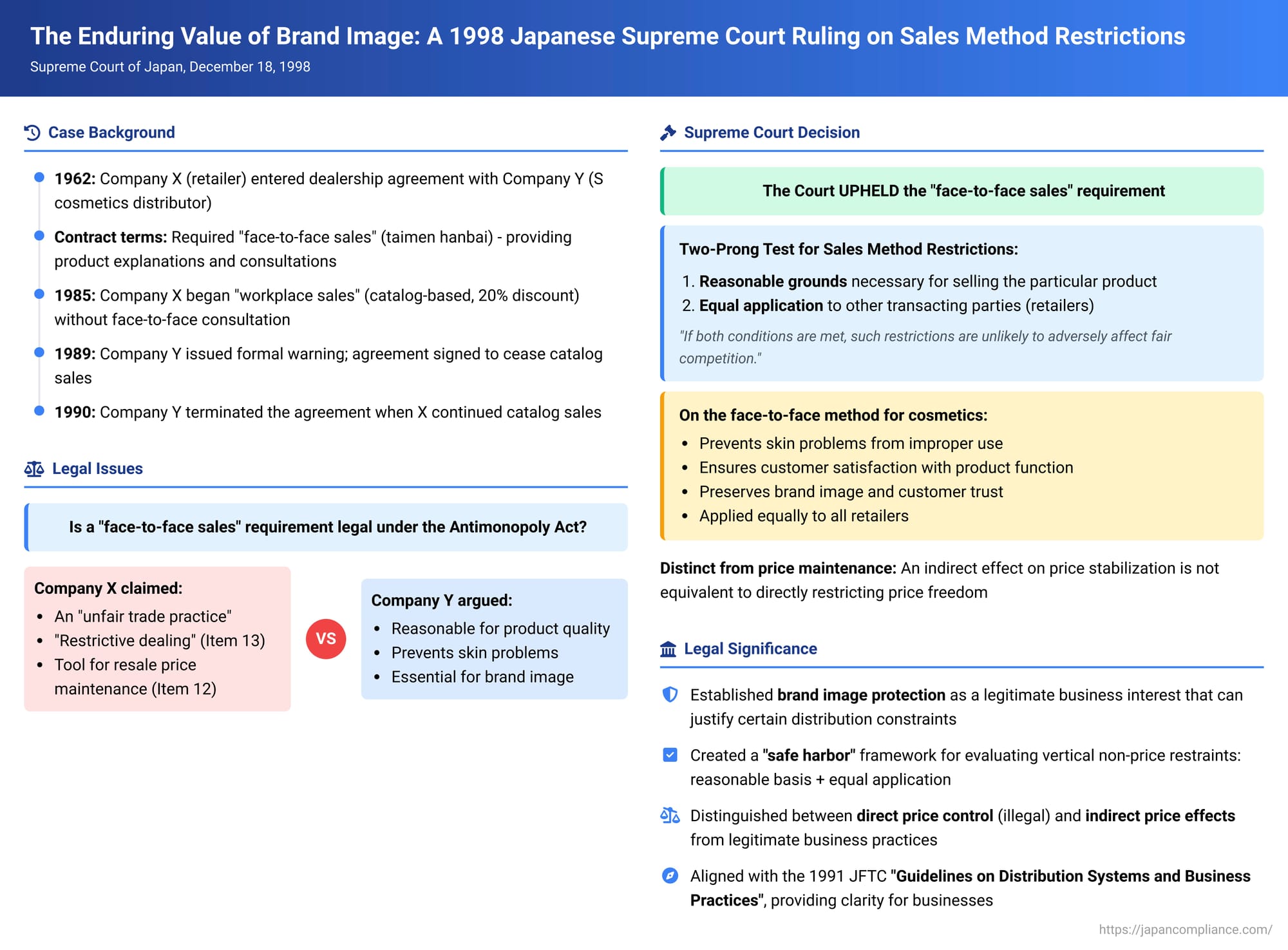

On December 18, 1998, Japan's Supreme Court delivered a significant judgment in a case concerning the intricate balance between a manufacturer's control over its product distribution and the principles of fair competition enshrined in the Antimonopoly Act. The case, involving a prominent cosmetics sales company and a retailer, revolved around the legality of terminating a dealership agreement due to the retailer's failure to adhere to a "face-to-face sales" clause. This ruling provides crucial insights into how Japanese courts approach vertical restraints, particularly sales method restrictions, and the legitimate business interests that can justify them.

The Genesis of the Dispute: Cosmetics, Contracts, and Competing Sales Models

The defendant, Company Y, was the sales arm for Company S, Japan's largest cosmetics manufacturer by sales revenue. Company Y specialized in distributing Company S's products. The plaintiff, Company X, was a retail business that had a long-standing dealership agreement with Company Y, originally established in 1962, to sell Company S cosmetics. This agreement was based on a standard "S Chain Store Agreement" that Company Y used with all its retailers.

Central to this dispute were specific clauses within the dealership agreement. The contract had a one-year term, automatically renewable if neither party objected. However, it also contained a provision allowing either party to terminate the agreement mid-term with 30 days' written notice (referred to as the "Termination Clause").

Crucially, the agreement mandated that dealers, including Company X, adhere to certain sales practices. These included setting up a dedicated section for Company S cosmetics, attending beauty seminars hosted by Company Y, and, most importantly, engaging in what was termed "face-to-face sales" (taimen hanbai). This required retailers to provide customers with explanations on how to use the cosmetics and to be available for consultations regarding the products.

Company Y articulated clear reasons for insisting on this taimen hanbai method. Firstly, it aimed to proactively prevent skin problems that might arise from improper cosmetic use. Secondly, Company Y believed that selling cosmetics was not merely a transaction of goods but involved selling the function of becoming beautiful. Educating customers on the skillful application of products was therefore deemed essential to deliver this value and ensure customer satisfaction. This approach was intrinsically linked to maintaining and enhancing the premium brand image of Company S cosmetics. While it was acknowledged that some customers did purchase Company S products without extensive consultation, a significant volume of sales occurred through retailers who maintained dedicated counters and provided personalized advice.

In contrast to these contractual requirements, Company X, starting around February 1985, adopted a different sales strategy. It began distributing simple catalogs listing product names, prices, and product codes to workplaces. Orders were then collected via phone or fax, and the products, including Company S cosmetics, were delivered. Company X offered a 20% discount on these sales, which it termed "workplace sales" (shokuiki hanbai). Under this model, product explanations were minimal, typically limited to answers provided over the phone if a customer inquired. Face-to-face consultation, as envisioned by the dealership agreement, was entirely absent.

Company Y became aware of Company X's "workplace sales" method around the end of 1987. Initially, Company Y requested that Company X remove Company S cosmetics from its general catalog, and Company X complied. However, it later transpired that Company X had started using a separate catalog exclusively for Company S products. In response, on April 12, 1989, Company Y issued a formal written warning to Company X, stating that its sales method violated the taimen hanbai clause and other provisions of the dealership agreement, and demanded rectification. Following negotiations between legal representatives of both parties, an agreement was signed on September 19, 1989. In this agreement, Company X pledged to cease catalog-based sales of Company S cosmetics and to adhere to the sales methods stipulated in the dealership agreement. Notably, during these negotiations, Company Y did not raise any issue concerning Company X's discount pricing strategy.

Despite this written commitment, Company X showed no inclination to change its sales practices. Concluding that Company X had no intention of abandoning its "workplace sales" model, Company Y invoked the Termination Clause. On April 25, 1990, Company Y formally notified Company X of its decision to terminate the dealership agreement and subsequently ceased product shipments.

Company X contested the validity of this termination and filed a lawsuit. It sought confirmation of its status as a rightful recipient of Company S products under the dealership agreement and demanded the delivery of outstanding orders.

Navigating the Lower Courts: Divergent Interpretations

The case first went before the Tokyo District Court. The District Court found in favor of Company X, partially granting its claims. The court opined that the rationale behind the taimen hanbai clause was not sufficiently compelling. It questioned whether such a clause was reasonable enough to justify terminating a continuous supply contract with a retailer who did not strictly adhere to it. Furthermore, the District Court suggested that the taimen hanbai requirement, by restricting sales methods without a strong reasonable justification and potentially aiming to maintain prices, could be contrary to the spirit of Japan's Antimonopoly Act.

Company Y appealed this decision to the Tokyo High Court. The High Court overturned the District Court's ruling. It found that the taimen hanbai method was indeed a reasonable requirement for selling cosmetics. Given Company X's persistent and acknowledged breach of this contractual obligation, the High Court considered the violation to be more than trivial. It concluded that there were justifiable grounds for the termination of the agreement and dismissed Company X's claims. Aggrieved by this reversal, Company X appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Stance

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of December 18, 1998, dismissed Company X's appeal, thereby upholding the Tokyo High Court's decision in favor of Company Y. The core of Company X's argument before the Supreme Court was that the taimen hanbai clause constituted an "unfair trade practice" prohibited by Article 19 of the Antimonopoly Act. Specifically, Company X contended that the clause fell under "resale price maintenance" (as defined in Item 12 of General Designation No. 15 of 1982, issued by the Japan Fair Trade Commission under Article 2, Paragraph 9, Item 4 of the Act) and/or "restrictive dealing" (Item 13 of the same General Designation).

The Supreme Court meticulously analyzed these claims.

Addressing Restrictive Dealing (General Designation Item 13)

Article 19 of the Antimonopoly Act prohibits businesses from employing unfair trade practices. Article 2, Paragraph 9, Item 4 of the Act defines one category of unfair trade practices as engaging in transactions with restrictive conditions that unduly bind the counterparty's business activities, pose a risk of impeding fair competition, and are designated by the Fair Trade Commission (FTC). General Designation Item 13 specifically targets "dealing with a counterparty on conditions that unduly restrict transactions between that counterparty and its customers, or other business activities of that counterparty."

The Supreme Court acknowledged that restrictive dealing is regulated because conditions that constrain a counterparty's business activities—especially when a business imposes restraints on transactions between its direct counterparty and third parties that directly affect competition—can artificially hinder the competitive process, which should ideally manifest as providing high-quality, low-priced goods and services.

However, the Court also noted that restrictive conditions vary widely in form and impact. Therefore, the potential to impede fair competition must be assessed based on the specific nature, content, and degree of restraint. A practice is deemed an "undue" restraint only if it is likely to negatively affect the fair competitive order.

Crucially, the Supreme Court laid down a general principle: the freedom of manufacturers and wholesalers to choose their sales policies and methods should, as a rule, be respected. Building on this, the Court established a two-prong test for evaluating sales method restrictions, such as requiring retailers to explain products to customers or instructing them on quality control and display methods:

- Reasonable Grounds: The restriction must be based on "reasonable grounds" necessary for selling the particular product.

- Equal Application: The restriction must be imposed equally on other transacting parties (i.e., other retailers).

If both conditions are met, such sales method restrictions, in themselves, are unlikely to adversely affect fair competition and would not constitute "unduly" restrictive conditions under General Designation Item 13.

Applying this framework to the facts of the case:

- Reasonableness of Taimen Hanbai for Cosmetics: The Court found the taimen hanbai requirement for cosmetics to be reasonable. It was a method of selling cosmetics with added value—providing explanations, and offering consultations on selection and use (or at least maintaining a readiness to do so upon customer request). Company Y's rationale was to meet customer desires for effective cosmetic use and enhanced beauty outcomes, and to take precautions against skin problems like irritation. This approach, the Court reasoned, fostered customer satisfaction and preserved customer trust in Company S cosmetics, distinguishing them from other products—what is commonly known as "brand image." The Court emphasized that, given the nature of cosmetics, maintaining customer trust is self-evidently critical to competitiveness in the cosmetics market. Therefore, Company Y's adoption of the taimen hanbai sales method had a "reasonable basis."

- Equal Application to Other Dealers: The Court noted that Company Y had identical agreements with its other retailers, imposing the same taimen hanbai obligation. Furthermore, a considerable volume of Company S cosmetics was indeed being sold through this method.

Based on these findings, the Supreme Court concluded that obligating Company X to adhere to the taimen hanbai method did not constitute dealing with conditions that "unduly" restricted its business activities, as per General Designation Item 13.

Addressing Resale Price Maintenance (General Designation Item 12)

Next, the Court turned to the issue of resale price maintenance. General Designation Item 12 prohibits, without justifiable reason, "fixing the sales price of the goods for the counterparty and compelling them to maintain it, or otherwise restricting the counterparty's freedom to determine its sales prices for said goods." The Court acknowledged that if a sales method restriction is used as a means to achieve resale price maintenance, then such a method could indeed be problematic under the Antimonopoly Act from this perspective.

However, the Court also made an important distinction: imposing restrictions on sales methods might lead to increased sales expenses for retailers, which could, in turn, result in some stabilization of retail prices. But, the mere occurrence of such a price-stabilizing effect does not, by itself, mean that a retailer's freedom to determine prices has been directly restricted.

In the present case, the Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's factual finding that Company Y was not using the taimen hanbai requirement as a tool to enforce resale price maintenance against Company X. The evidence supported this conclusion.

Overall Conclusion of the Supreme Court

Having found that the taimen hanbai obligation did not fall afoul of either General Designation Item 13 (restrictive dealing) or Item 12 (resale price maintenance), the Supreme Court deemed the High Court's judgment to be correct. It rejected Company X's arguments, characterizing them as either disagreements with the lower court's findings of fact (which are typically within the purview of the lower courts) or as attempts to argue based on its own unique interpretation of the law. The Court also upheld the High Court's determination that the termination was not based on Company X's discount pricing but on its breach of the sales method clause, and that the termination did not violate principles of good faith or constitute an abuse of rights.

Broader Context and Implications of the Ruling

This 1998 Supreme Court decision did not arise in a vacuum. It reflected and reinforced prevailing interpretations of Japanese antitrust law concerning vertical restraints, particularly in the context of distribution strategies.

At the time, the cosmetics in question were often categorized as "system goods" (seido hin). These were typically high-end products from major manufacturers, distributed through selective networks of retailers who were expected to provide counseling and sell at manufacturer-suggested retail prices. While formal resale price maintenance for most cosmetics had been largely deregulated by the period of the dispute (legal RPM had been limited to cosmetics under a certain price point, and these exemptions were further narrowed by 1993 and eventually abolished in 1997), the practice of taimen hanbai was sometimes viewed with suspicion as an indirect mechanism contributing to price rigidity in the market.

The Supreme Court's reasoning in this case closely aligns with the Japan Fair Trade Commission's "Guidelines on Distribution Systems and Business Practices" (first issued in 1991). These guidelines clarified that restrictions imposed by manufacturers on retailers' sales methods (excluding direct restrictions on price, sales territory, or customers) are generally not considered problematic under the Antimonopoly Act, provided two conditions are met:

- There is a "reasonable justification" for such restrictions to ensure the appropriate sale of the product (e.g., safety, quality, brand image).

- Equivalent conditions are applied to other retailers.

The Supreme Court's adoption of a similar two-prong test—"reasonable grounds" and "equal application"—is significant. This test can be seen as establishing a kind of "safe harbor" for businesses. If these conditions are satisfied, sales method restrictions are generally presumed lawful and not "unduly restrictive." This provides a degree of predictability for businesses structuring their distribution systems.

The Court’s distinction between an indirect effect of price stabilization and the act of illegal resale price maintenance is also noteworthy. Many legitimate business practices might increase operational costs, which can influence prices. However, the ruling clarifies that such ancillary effects do not automatically render a practice illegal unless it can be shown that the primary purpose or direct effect is to unlawfully restrict price competition.

Furthermore, the judgment underscores the legitimacy of "brand image" and "customer trust" as significant business interests that can justify certain sales methods, especially for products like cosmetics where consumer perception and confidence are paramount. The Court recognized that maintaining a particular brand identity, built through quality products and service, is a valid competitive strategy.

It is also worth noting that another Supreme Court judgment on a similar issue (Heisei 6 (O) No. 2156) was delivered around the same time. That case also upheld the validity of requiring counseling sales for cosmetics and, importantly, affirmed the legality of prohibiting wholesale distribution to retailers who were not part of the manufacturer's selective dealership network. This prohibition was seen as a necessary corollary to the counseling sales obligation, as allowing products to flow to non-contracted retailers who would not provide such services would undermine the entire system. This parallel ruling indicated a consistent judicial approach to these types of vertical restraints aimed at preserving product quality, service standards, and brand integrity.

Concluding Thoughts

The December 1998 Supreme Court decision in the case between Company X and Company Y stands as a key precedent in Japanese antitrust law concerning sales method restrictions. It affirms that while the Antimonopoly Act aims to prevent practices that unfairly stifle competition, it also respects the legitimate freedom of businesses to devise and implement sales strategies appropriate for their products and brand positioning.

The ruling provides a clear framework: sales method requirements, even if they impose certain burdens on retailers, are generally permissible if they are grounded in reasonable business justifications specific to the product and are applied non-discriminatorily across all dealers. The Court's careful distinction between such legitimate requirements and genuinely anticompetitive practices like resale price maintenance or undue restrictions on business activity offers valuable guidance. It highlights a nuanced understanding that protecting brand image and ensuring customer satisfaction through specialized sales methods can be valid pro-competitive objectives, ultimately benefiting both businesses and consumers in the marketplace.