The Employer's Right to Lockout in Japan: The Landmark Marushima Suimon Case (Supreme Court, April 25, 1975)

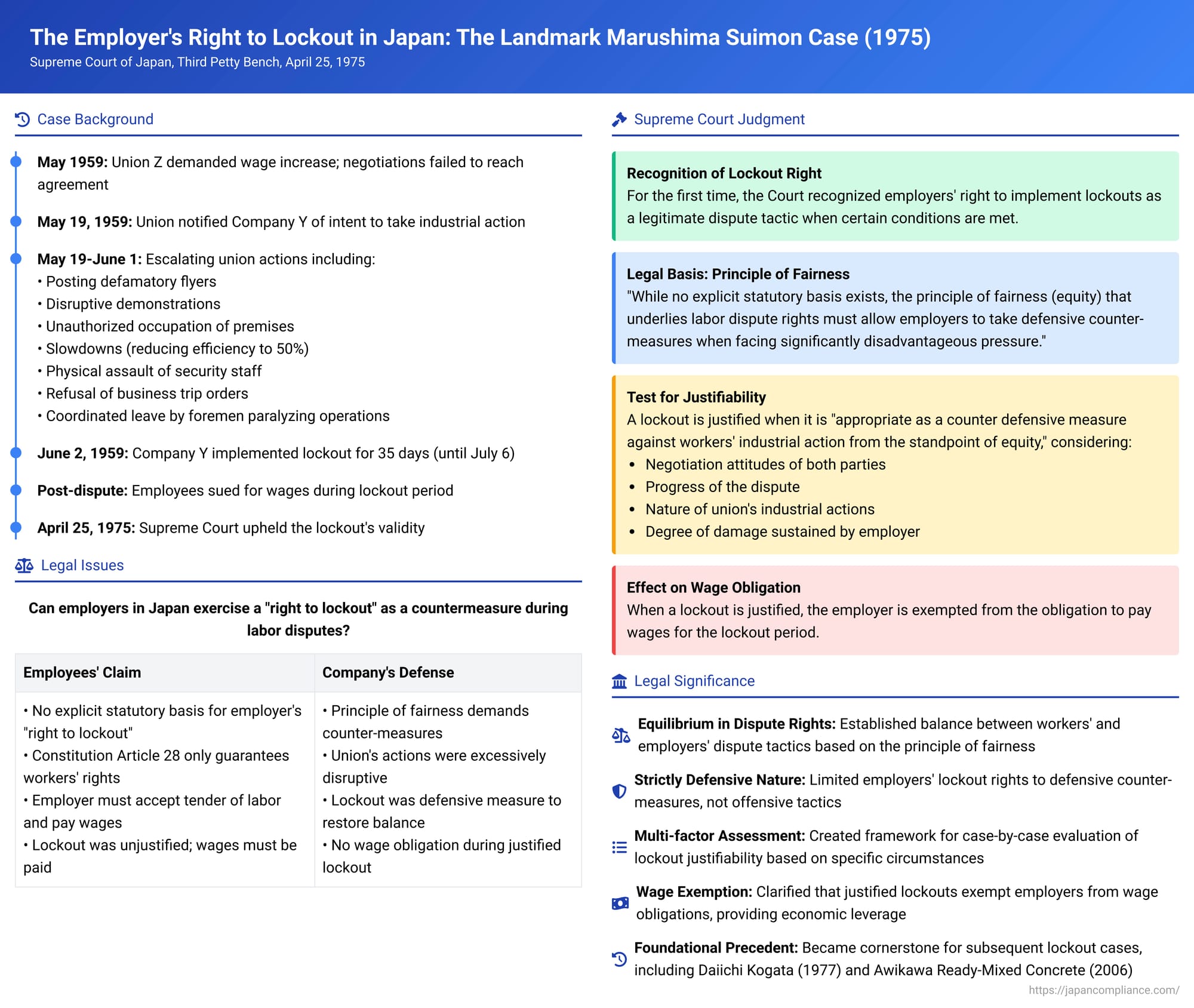

On April 25, 1975, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a seminal judgment in the case commonly known as the Marushima Suimon Seisakusho (Sluice Gate Manufacturing) case. This ruling was groundbreaking as it was the first time the nation's highest court explicitly recognized an employer's right to engage in a lockout as a legitimate countermeasure during a labor dispute, provided certain conditions of justifiability were met. The case meticulously laid out the legal basis and the requirements for such an employer's dispute act.

Case Reference: 1969 (O) No. 1256 (Wage Claim Case)

Appellants (Original Plaintiffs): Mr. X et al. (Motoharu Okada and 12 others, representing union members)

Appellee (Original Defendant): Company Y (Marushima Suimon Seisakusho Co., Ltd.)

Judgment of the Supreme Court: The appeal is dismissed. The appellants shall bear the court costs.

Factual Background: An Escalating Labor Dispute

The case arose from a period of intense labor strife between Company Y, a manufacturer of sluice gates, and its employees, Mr. X et al., who were members of Union Z.

- Breakdown of Negotiations: In early May 1959, Union Z demanded a wage increase. Despite several rounds of collective bargaining with Company Y, no agreement was reached.

- Commencement of Industrial Action: On May 19, 1959, the union notified Company Y of its intent to engage in industrial action. The union's actions progressively intensified:

- Members posted flyers slandering Company Y and its officers on factory and office walls during lunch breaks and before work.

- They conducted disruptive demonstrations inside the office, shouting and hindering the duties of company executives.

- Broadcasts were made using portable loudspeakers, defaming the company and its officers.

- Approximately 20 union members remained on company premises without permission after work hours, refusing requests to leave.

- From around May 22, a slowdown (sabotage or taigyō) began, and by May 27, operational efficiency had reportedly dropped to about half of normal levels.

- Company Y's attempts to reinforce supervision were met with obstruction by union members. In one incident, a security staff member accompanying an executive was physically assaulted and injured.

- Nine union members refused business trip orders.

- On June 1, a coordinated leave by seven out of eight foremen and deputy foremen (who were union members) paralyzed the work process, making normal operations impossible.

- The Lockout: Believing that the union's actions had severely reduced operational efficiency, made normal business conduct difficult, and posed a threat to the company's management, Company Y notified the union members of a lockout on June 2, 1959. This lockout continued for 35 days until it was lifted on July 6.

- Wage Claims: After the dispute ended, Mr. X et al. sued Company Y for wages for the period of the lockout, arguing that the company's refusal to allow them to work was unjustified.

Procedural History

- The District Court (Osaka District Court, judgment May 16, 1964) ruled in favor of the employees, ordering Company Y to pay the wages.

- The High Court (Osaka High Court, judgment September 19, 1969) overturned the District Court's decision, ruling against the employees and dismissing their wage claims.

Mr. X et al. then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed the employees' appeal, upholding the High Court's decision to deny wages. The core of its reasoning involved recognizing a conditional right for employers to engage in defensive lockouts.

I. Legal Basis for Employer's Right to Dispute (Lockout)

The Court began by acknowledging that Article 28 of the Constitution and various labor laws explicitly guarantee the right to dispute (including the right to strike) to workers to help equalize their bargaining power with employers. These laws do not contain corresponding provisions for an employer's right to dispute.

However, the Court reasoned that simply concluding from this that employers have no right to dispute whatsoever, and are limited to actions permissible under general civil law, would not be appropriate. The Court's logic was as follows:

- The fundamental purpose of recognizing the right to dispute is to free such actions from the constraints of general civil law, thereby promoting and ensuring equality between labor and management. This is ultimately based on the principle of fairness (equity).

- While employers are generally in a position of strength and thus do not typically require a "right to dispute" in the same vein as workers, there can be situations in specific labor disputes where workers' actions disrupt this balance of power, placing the employer under significantly disadvantageous pressure.

- In such cases, based on the principle of fairness, the employer should be permitted to take counter defensive measures to prevent such pressure and restore the balance of power between the parties. To this extent, an employer's dispute act can be recognized as justifiable.

II. Justifiability of a Lockout

The Court then applied this framework to lockouts specifically:

- A lockout, defined as the collective refusal to accept the tender of labor from workers (i.e., a workplace closure), is one form of employer's dispute act.

- Its justifiability – whether an employer can refuse to accept labor, free from the constraints of general civil law – must be determined by considering various specific circumstances of the particular labor dispute. These include:

- The negotiation attitudes of both labor and management.

- The progress of the dispute.

- The nature of the union's industrial actions.

- The degree of damage or impact sustained by the employer due to the union's actions.

- Based on these factors, if the lockout is deemed "appropriate as a counter defensive measure against the workers' industrial action from the standpoint of equity," then it is considered a justifiable dispute act.

- In such a case of a justifiable lockout, the employer is exempted from the obligation to pay wages to the targeted employees for the duration of the lockout under their individual employment contracts.

III. Application to the Facts of the Marushima Suimon Case

The Supreme Court reviewed the High Court's findings regarding the union's conduct leading up to the lockout:

- The union's industrial actions were "considerably fierce, accompanied by acts of violence."

- The slowdown (sabotage) gradually worsened.

- The dispute escalated to include refusals of business trip orders and a partial strike in the form of a coordinated mass leave by foremen and deputy foremen.

- This series of actions by the union created a risk of hindering Company Y's operations and jeopardizing its business.

- Consequently, Company Y implemented the lockout "to cope with such a situation, by temporarily closing the workplace in opposition to the union's industrial action."

The Supreme Court concluded that, under these specific circumstances, Company Y's lockout was "appropriate as a counter defensive measure against the workers' industrial action from the standpoint of equity." Therefore, the lockout was justifiable, and the High Court's decision denying the employees' wage claims was correct.

Analysis and Significance of the Ruling

The Marushima Suimon case is a landmark decision in Japanese labor law for several reasons:

- Establishment of the Employer's Right to Lockout:

This was the first Supreme Court ruling to definitively acknowledge that employers in Japan have a right to implement a lockout as a legitimate form of industrial dispute, provided specific conditions are met. Prior to this, legal opinion was divided. The "civil law approach" denied any special right to lockout, treating employer actions under general contract law principles (like default in acceptance or risk allocation). The "labor law approach," which this judgment adopted, recognized the lockout as an employer's dispute tactic, and if justifiable, it would exempt the employer from wage obligations. - Legal Basis in the "Principle of Fairness":

Instead of finding an explicit statutory basis for the employer's right to dispute (which doesn't exist in Japanese law), the Court ingeniously grounded it in the "principle of fairness (equity)." This principle underpins the workers' right to dispute, and the Court extended it to employers in limited, defensive scenarios to restore a disrupted balance of power. - Strictly Defensive Nature:

The Court emphasized that a justifiable lockout must be a "counter defensive measure." It is not an offensive tool for employers to unilaterally impose their will but a reactive measure to significantly disruptive industrial action by workers. This ensures that the employer's power is not unduly expanded. - Conditions for Justifiability:

The judgment laid out crucial conditions for a lockout to be deemed justifiable:- It must be a response to workers' industrial action.

- The employer must be facing "significantly disadvantageous pressure" due to the workers' actions, disrupting the balance of power.

- The lockout must be a necessary means to "prevent such pressure and restore the balance of power."

Essentially, the lockout's "appropriateness as a defensive measure from the standpoint of equity against the workers' dispute acts" is the overarching test.

- Factors Determining "Appropriateness":

The Court identified several factors to consider when assessing appropriateness: "the negotiation attitudes of both labor and management, the progress of the dispute, the nature of the union's industrial actions, and the degree of damage or impact sustained by the employer." While these criteria are somewhat abstract and have been criticized for potentially lacking predictability, they reflect the need for a case-by-case analysis sensitive to the dynamic nature of labor disputes. - Exemption from Wage Payment:

A critical consequence of a justifiable lockout, as affirmed by this judgment, is that the employer is relieved of the obligation to pay wages to the locked-out employees for the duration of the lockout. This is a significant tool for employers, particularly when facing tactics like slowdowns or partial strikes where traditional wage cuts for non-performance are complex but operational damage is severe. - Influence on Subsequent Case Law:

The framework established in Marushima Suimon has been consistently applied in subsequent Supreme Court decisions concerning lockouts. Later cases have further refined these principles. For instance, the Daiichi Kogata Hired Car case (Supreme Court, 1977) clarified that "appropriateness" is not only a requirement for initiating a lockout but also for its continuation. The Awikawa Ready-Mixed Concrete Industry case (Supreme Court, 2006) provided a concrete example of "negotiation attitudes," deeming it unreasonable for workers to make demands contrary to a prior agreement shortly after switching unions and initiating a dispute.

Conclusion

The Marushima Suimon Seisakusho case stands as a cornerstone of Japanese labor law regarding employers' rights during industrial disputes. By recognizing a conditional, defensive right to lockout grounded in the principle of fairness, the Supreme Court provided a legal framework for employers to counteract excessively disruptive industrial action by workers. While the right is carefully circumscribed and requires a rigorous assessment of its justifiability based on the specific circumstances of each dispute, this judgment acknowledged the need for employers to have legitimate means to protect their operational interests and restore equilibrium when the balance of power is severely tilted against them.