The Employee's Right to Say "Stop": Supreme Court Clarifies Check-Off Agreement Limits in Esso Sekiyu Case

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of March 25, 1993 (Case No. 1991 (O) No. 928: Claim for Damages)

Appellant (Employer): Y Company

Appellees (Employees): X (and others)

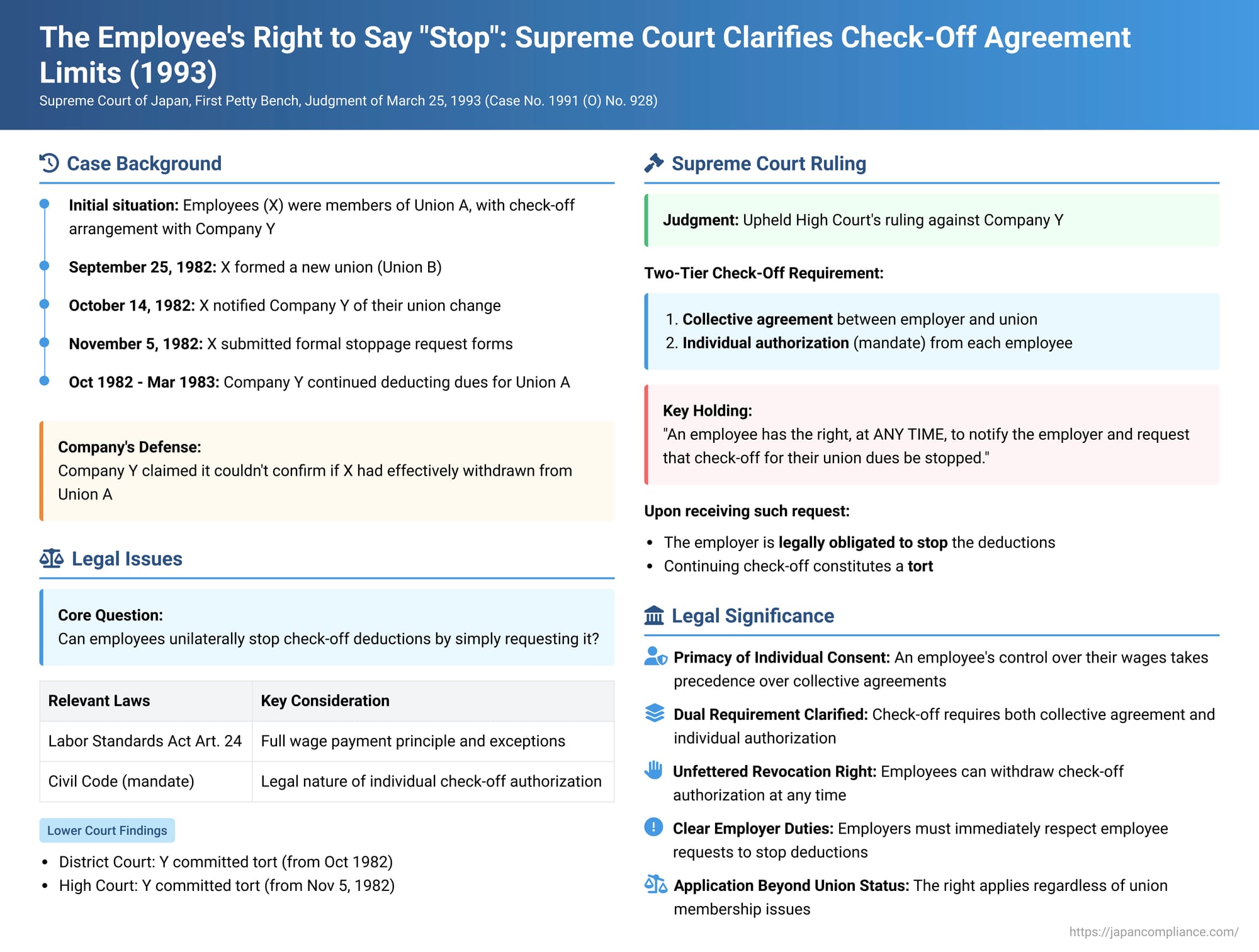

The check-off system, whereby an employer deducts union dues directly from employees' wages and remits them to the labor union, is a widespread practice in Japan, valued by unions for its efficiency in dues collection. However, the legal underpinnings of this practice, particularly the rights of individual employees to stop such deductions, were significantly clarified by the Japanese Supreme Court in its judgment on March 25, 1993, in the Esso Sekiyu (Esso Oil) case. This decision emphasized the primacy of individual employee consent for wage deductions, even when a collective check-off agreement exists between the employer and a union.

The Factual Backdrop: A Union Switch and Continued Deductions

The dispute arose within Y Company. The plaintiffs, X (a group of employees), were initially members of A Union, which had a check-off agreement with Y Company. Due to internal policy disagreements, X and other employees became significantly opposed to A Union's leadership.

This dissatisfaction culminated in a shift of allegiance:

- On September 25, 1982, X and their colleagues formed a new labor union, B Union.

- By October 14, 1982, all members of the X group had joined B Union and had formally notified Y Company of this change.

Following their move to B Union, the employees sought to redirect their union dues:

- On October 12, 1982, B Union sent a written request to Y Company to change the designated bank account for the transfer of its members' union dues.

- Subsequently, on November 5, 1982, B Union submitted another document to Y Company. This communication included individual "union dues deduction stoppage request forms" prepared and signed by each of the X employees who had joined B Union.

Despite these notifications and requests, Y Company continued to deduct amounts equivalent to A Union's dues from X's monthly wages from October 25, 1982, through March 25, 1983, as well as from a bonus paid in November 1982. These deducted amounts were then paid over to A Union. Y Company's stated reason for continuing the check-off for A Union was its inability to definitively confirm that X had, in fact, effectively withdrawn their membership from A Union.

Believing these continued deductions to be unlawful, X filed a lawsuit against Y Company, seeking damages on the grounds that the check-off constituted a tortious act.

Lower Court Rulings

The First Instance court (Osaka District Court, October 19, 1989) found in favor of X. It determined that X had effectively ceased to be members of A Union by October 14, 1982, and that Y Company was in a position to be aware of this. Consequently, the court held that the check-offs from October 1982 onwards were unlawful and constituted a tort, granting X's claim for damages related to these deductions.

The High Court (Osaka High Court, February 26, 1991) also ruled that Y Company had committed a tort by continuing the deductions. However, it pinpointed November 5, 1982—the date X submitted their individual deduction stoppage requests—as the legally significant moment when X's intention to revoke the check-off authorization was clearly manifested to Y Company. Thus, the High Court awarded damages for the deductions made from November 1982 onwards. Y Company appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Stance on Check-Off

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Company's appeal, upholding the High Court's finding of liability. In its reasoning, the Supreme Court laid down clear and authoritative principles regarding the legal nature and operation of check-off agreements:

1. Check-Off Agreements and the Labor Standards Act (LSA) Article 24:

The Court first addressed the effect of check-off agreements in relation to Article 24, Paragraph 1 of the Labor Standards Act. This article establishes the "full wage payment principle," mandating that employers pay employees their full wages directly, in currency, etc. However, the proviso to this article allows for exceptions, including deductions made based on a written agreement with a labor union representing a majority of employees at the workplace (or with a representative of the majority if no such union exists).

The Supreme Court clarified:

- A check-off agreement that fulfills the requirements of the LSA Article 24 proviso primarily serves to make the employer's check-off an exception to the full wage payment principle. This means the employer is shielded from penalties (under LSA Article 120, Item 1) that would otherwise apply for making unauthorized deductions from wages.

- Crucially, even if such a check-off agreement is formalized as a collective labor agreement, it does not, in itself, automatically grant the employer the legal authority or power to make check-off deductions from an individual employee's wages.

- Furthermore, such a collective agreement does not inherently impose an obligation on individual union members to passively accept or tolerate such deductions from their pay.

2. The Indispensable Role of Individual Employee Authorization (Mandate):

This was the linchpin of the Supreme Court's decision. The Court unequivocally stated that for an employer to validly conduct check-off, two distinct layers of consent are necessary:

a. The collective check-off agreement between the employer and the labor union.

b. Beyond this collective agreement, the employer must also obtain individual authorization (a mandate or inin) from each specific union member. This individual authorization empowers the employer to deduct the union dues from that member's wages and remit them to the union on their behalf.

If this individual authorization from a particular member is absent, the employer has no legal right to make check-off deductions from that member's wages, regardless of the existence of a broader collective agreement with the union.

3. The Unfettered Right of an Employee to Revoke Individual Authorization:

Flowing directly from the necessity of individual authorization, the Supreme Court affirmed an employee's right to withdraw that authorization:

- Even if check-off has already commenced for an employee based on their prior authorization, that employee retains the right, at any time, to notify the employer and request that the check-off for their union dues be stopped.

- Upon receiving such a request from an individual employee to cease deductions, the employer is legally obligated to stop making check-off deductions for that specific employee.

This right to revoke is an individual right and is not contingent on the employee's membership status in the union that is party to the check-off agreement, nor is it contingent on the terms of the collective check-off agreement itself. This directly addressed Y Company's defense that it was unsure if X had properly left A Union. The act of X requesting Y Company to stop the deductions was sufficient to terminate Y Company's authority to make those deductions from X's wages for A Union.

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found no error in the High Court's judgment, which had held Y Company liable for continuing the check-off after X's members had clearly requested a halt.

Significance and Implications of the Esso Judgment

The Esso Sekiyu Supreme Court decision has several far-reaching implications for labor relations and the administration of union dues in Japan:

- Primacy of Individual Consent over Wages: The judgment strongly underscores the principle that an individual employee's explicit consent is paramount for any deductions from their wages, including those for union dues. A collective agreement, while important for other labor relations matters, cannot unilaterally override an individual's control over their earned wages in this context.

- Clarification of the Dual Requirement for Check-Off: It definitively established the two-tiered legal basis for check-off: a collective agreement (often with a majority union, to comply with LSA Article 24) and specific individual authorization from each concerned employee. The PDF commentary notes that this frames check-off heavily on the individual authorization aspect.

- Empowerment of Individual Employees: The ruling empowers individual employees by affirming their right to control whether their union dues are deducted via check-off. They can initiate it, and more importantly, they can stop it at their discretion by notifying the employer.

- Impact on Union Dues Collection: While check-off provides a convenient and reliable method for unions to collect dues, this judgment means that unions cannot solely depend on a collective agreement with the employer to guarantee dues collection through payroll deduction if individual members choose to revoke their consent.

- Clear Guidance for Employers: The decision provides unambiguous guidance for employers: they have a legal duty to cease check-off for an individual employee upon receiving a clear request from that employee to do so. Continuing deductions in the face of such a request can lead to legal liability for damages, as seen in this case. An employer's uncertainty about an employee's formal membership status in a particular union is not a valid defense for ignoring a direct request to stop deductions.

- Relationship with LSA Article 24 (Full Wage Payment Principle): The PDF commentary discusses the judgment's grounding in the context of LSA Article 24. Earlier cases, like the S C H case, had already established that a check-off agreement (typically with a majority union) is necessary for the employer to legally make deductions without violating the full wage principle. The Esso judgment builds upon this by clarifying the employee's individual rights within that system, establishing that the LSA Article 24-compliant collective agreement is a necessary but not sufficient condition for deducting from a specific employee. Individual consent is the other vital component.

- Consistent Supreme Court Stance: The Supreme Court has reaffirmed this position in subsequent rulings, such as the N J (T/S) case and the N J (K P) case.

Scholarly Perspectives

It's worth noting, as pointed out in the provided PDF commentary, that while the Supreme Court's position is clear, it is not without academic debate. Many labor law scholars in Japan argue for a perspective that accords greater weight to the collective agreement (specifically, a labor contract with "normative effect" under the Labor Union Act) in binding union members to check-off arrangements for as long as they remain members of the signatory union. These views often emphasize the collective aspects of labor relations and the role of check-off in ensuring union stability. The Esso judgment, by contrast, leans more towards an individual rights-based interpretation of the check-off mechanism.

Conclusion

The Esso Sekiyu Supreme Court judgment of 1993 is a landmark decision in Japanese labor law. It champions the individual employee's right to control deductions from their wages, specifically concerning union dues collected via check-off. By requiring both a collective agreement and, crucially, ongoing individual employee authorization, and by affirming the employee's right to revoke that authorization at any time, the Court placed significant limitations on the otherwise automatic operation of check-off systems. This ruling continues to provide essential guidance for employers, employees, and unions in navigating the legalities of union dues collection in Japan.