The Elusive Quarry: Interpreting "Capture" in Japanese Wildlife Protection Law – The Case of W

Date of Judgment: February 8, 1996

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Case Number: 1995 (A) No. 437

I. Introduction: The Arrow that Missed and the Question of "Capture"

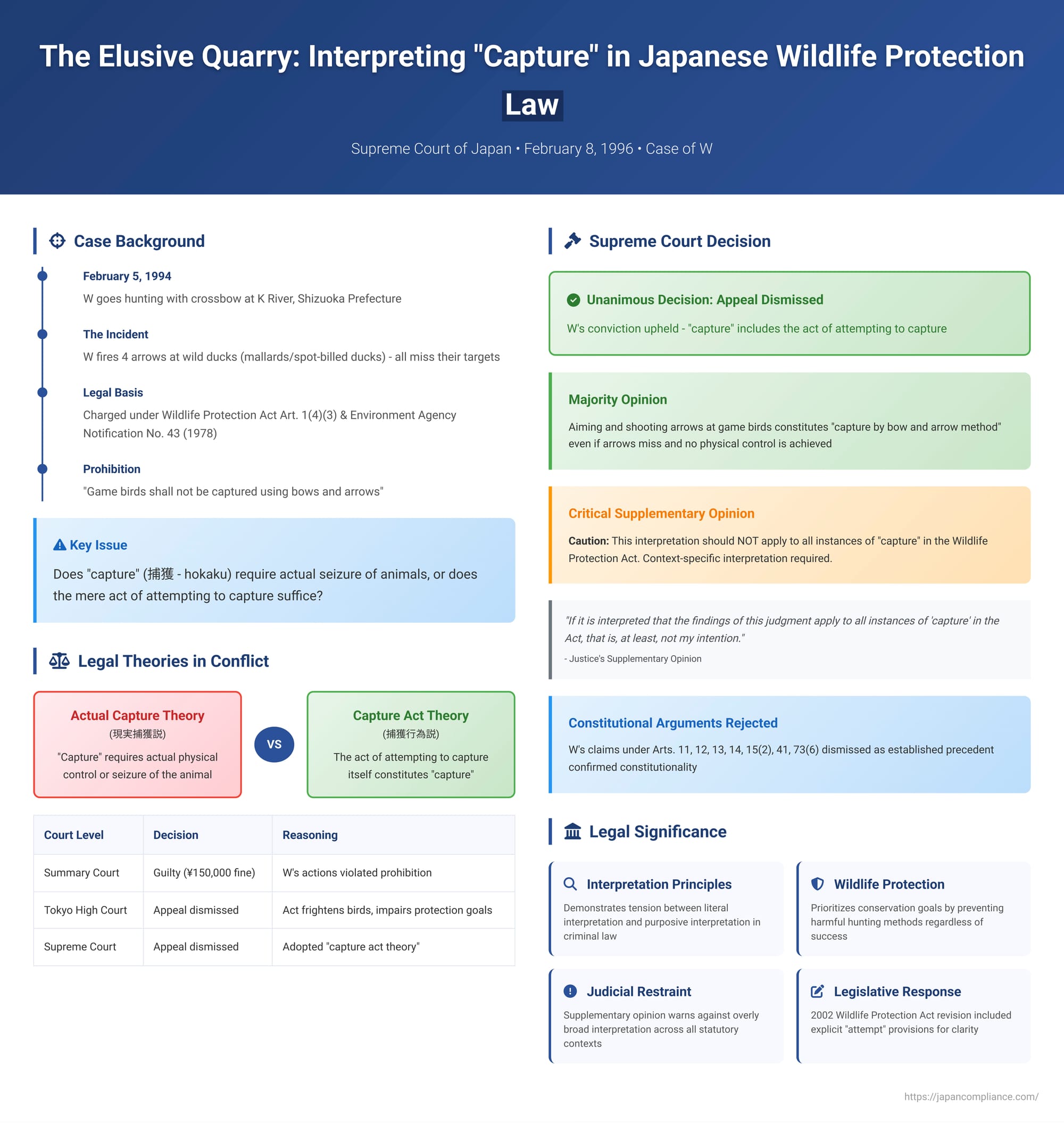

On February 8, 1996, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment in a case that, on its surface, concerned a frustrated hunter and a few missed shots. However, the case of W delved into profound questions at the heart of Japanese penal law: how statutory language should be interpreted, the limits of judicial interpretation, and the crucial balance between achieving a law's protective aims and upholding the principle that no one should be punished for an act not clearly defined as a crime. The central issue revolved around the meaning of "capture" (捕獲 - hokaku) under Japan's then-operative wildlife protection legislation. Did it necessitate the actual taking of an animal, or could the mere act of attempting to do so, even if unsuccessful, suffice to constitute the prohibited act?

II. The Incident: A Crossbow, Ducks, and an Unsuccessful Hunt

The facts of the case were straightforward. On the afternoon of February 5, 1994, W ventured to the K River riverbed in Shizuoka Prefecture. He was equipped with a crossbow and arrows, his intention being to hunt wild ducks (either mallards or spot-billed ducks, both considered game birds) for his own consumption. W fired four arrows at the ducks. However, his aim was off; none of the arrows struck their targets. The ducks, unharmed, flew away, and W failed to secure any. This seemingly simple sequence of events would lead W through the Japanese judicial system, up to its highest court.

III. The Legal Gauntlet: Navigating Japan's Wildlife Protection Law

W was prosecuted for violating the "Law for the Protection of Birds and Beasts and for Hunting" (鳥獣保護及狩猟ニ関スル法律 - Chōjū Hogo Oyobi Shuryō ni Kansuru Hōritsu), often referred to as the Old Wildlife Protection Act as it was significantly revised in 2002. The specific provision under scrutiny was Article 1, Section 4, Paragraph 3. This article empowered the Director-General of the Environment Agency (now Ministry of the Environment) to prohibit or restrict the capture of game birds by designating the type of bird, area, period, or hunting method, if deemed necessary for the protection and breeding of said game birds.

Acting under this authority, the Environment Agency had issued Notification No. 43 in 1978. Item 3, sub-item 'ri' (リ) of this notification stipulated that "game birds shall not be captured using the following hunting methods: ... (ri) methods using bows and arrows." The prosecution argued that W's actions – shooting arrows from a crossbow at game birds – constituted "capture" by a prohibited method, thereby violating the Act. The potential penalty was imprisonment for up to six months or a fine of up to 300,000 yen, as per Article 22, Item 2 of the Old Wildlife Protection Act.

IV. Lower Court Battles: Defining "Capture" Broadly

The Numazu Summary Court, the court of first instance, found W guilty on September 30, 1994, imposing a fine of 150,000 yen. W appealed this decision.

The Tokyo High Court heard the appeal and, on April 13, 1995, dismissed it, upholding the guilty verdict. The High Court's reasoning was significant. It opined that "the act of aiming and shooting arrows with a crossbow at game birds, even if it does not kill or injure them, frightens not only the targeted birds but also other birds in the vicinity." Therefore, such an act "substantially impairs the protection and breeding of game birds, which is the purpose of the delegation under Article 1, Section 4, Paragraph 3 of the Wildlife Protection Act and the objective of Notification No. 43." Consequently, the High Court concluded that W's actions did indeed fall under the definition of "capture" prohibited by the regulation. W, maintaining his innocence or at least that his actions did not legally constitute "capture," appealed to the Supreme Court.

V. The Supreme Court's Verdict: Upholding a Wider Interpretation

The Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, issued its judgment on February 8, 1996, dismissing W's final appeal.

The Court addressed W's constitutional arguments first. W had contended that Article 1, Section 4, Paragraph 3 of the Old Wildlife Protection Act and the enabling Environment Agency Notification No. 43, Item 3 (ri) were unconstitutional, citing violations of Articles 11 (eternal and inviolate fundamental human rights), 12 (duty to maintain freedoms and rights), 13 (respect for individuals, pursuit of happiness), 14 (equality under the law), 15 Paragraph 2 (right to dismiss public officials), 41 (Diet as the sole law-making organ), and 73 Item 6 (Cabinet's power to enact cabinet orders, with delegation rules) of the Constitution of Japan. The Supreme Court summarily dismissed these claims, stating that it was clear from established precedents that the provisions in question were not unconstitutional. The remaining grounds of appeal, including those framed as constitutional violations, were deemed by the Court to be, in substance, mere assertions of statutory misinterpretation or factual errors, which are not permissible grounds for a final appeal under Article 405 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

Turning to the core issue of interpreting "capture," the Supreme Court affirmed the Tokyo High Court's judgment as "just." It stated: "Regarding the act of aiming and shooting arrows with a crossbow at game birds (mallards or spot-billed ducks) for the purpose of consumption, the original judgment, which found that this constitutes capture by the method of using bows and arrows prohibited by Notification No. 43, Item 3 (ri) under Article 1, Section 4, Paragraph 3 of the Wildlife Protection Act, even if the arrows missed, the birds were not brought under one's physical control, and no injury or death occurred, is proper."

In reaching this conclusion, the Supreme Court referenced two of its own prior decisions:

- Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Decision of February 3, 1978 (Case 1977 (A) No. 740; Keishu Vol. 32, No. 1, p. 23). This case concerned Article 15 of the Act (restrictions on capture means).

- Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Decision of July 31, 1979 (Case 1979 (A) No. 365; Keishu Vol. 33, No. 5, p. 494). This case concerned Article 11 of the Act (prohibition of capture in certain places, restrictions on shooting).

These references indicated that the Supreme Court had previously adopted a broader interpretation of "capture" in the context of other restrictive provisions within the same Wildlife Protection Act, leaning towards what is often termed the "capture act theory" (捕獲行為説 - hokaku kōi setsu)—that the act of attempting to capture itself can be sufficient—rather than a strict "actual capture theory" (現実捕獲説 - genjitsu hokaku setsu) which would require the animal to be actually taken or killed.

VI. A Deeper Dive: The Supplementary Opinion's Cautionary Note

Adding significant nuance to the judgment, one Justice appended a supplementary opinion. While concurring with the majority's decision that W's actions constituted the prohibited "capture" in this specific instance, the Justice elaborated on the complexities surrounding the interpretation of "capture" (hokaku) within the Wildlife Protection Act.

The supplementary opinion began by acknowledging that the meaning of "capture" had been a contentious issue, with lower court precedents diverging. The root of this divergence, the Justice suggested, lay in the fact that "capture" could not be interpreted uniformly across all provisions of the Act.

Linguistically, the term "capture" is generally understood to mean "to seize, to capture alive, to take possession of." Under this common understanding, an attempt to capture that fails (an "attempted capture" or 未遂 - misui) would not be included. Therefore, to interpret "capture" as inherently including the mere act of attempting to capture, regardless of success, presents difficulties from a purely literal standpoint (文理上困難 - bunrijō konnan).

However, the Justice pointed out that some provisions within the Wildlife Protection Act would become irrational or fail to meet their legislative intent and purpose if "capture" were not interpreted to include the "act of capturing" (捕獲行為 - hokakukōi). The Supreme Court precedents cited by the majority concerning Articles 11 and 15 of the Act were examples of this. In those cases, the Court, focusing on the danger posed by the prohibited hunting methods themselves, had held that "capture" encompassed the act of attempting to capture, whether or not the animal was actually brought under control.

The Justice reasoned that the regulation in W's case – Environment Agency Notification No. 43, Item 3, prohibiting certain hunting methods like using bows and arrows – similarly aimed to generally ban specific hunting methods that posed a high risk of negative impact on the protection of game birds. Given this regulatory purpose, it was appropriate to interpret "capture" in this context as prohibiting the act of using such methods itself.

Crucially, the supplementary opinion then issued a strong caution. The Justice clarified that this purposive interpretation, while appropriate for the specific provision in W's case and for Articles 11 and 15 as decided previously, should not be automatically applied to every instance of the word "capture" throughout the Wildlife Protection Act. The opinion stated: "If it is interpreted that the findings of this judgment apply to all instances of 'capture' in the Act, that is, at least, not my intention."

For provisions where "capture" cannot reasonably be interpreted to include the mere act of attempting capture, if there is a societal need to penalize such attempts, the solution lies in legislative action – specifically, amending the law to create explicit "attempt" offenses. The Justice warned against unduly expanding interpretation (不当に拡張解釈すること - futōni kakuchō kaishaku suru koto) driven by the perceived need for regulation, emphasizing that such a practice must be strictly avoided. This concluding remark underscored a deep respect for the principle of legality and the distinct roles of the judiciary (to interpret laws) and the legislature (to make laws). The Justice added this note because some administrative interpretations and academic theories seemed to suggest that "capture" in the Act always included the "act of capture."

VII. Interpreting Penal Law in Japan: A Balancing Act

W's case serves as an excellent illustration of the intricate process of statutory interpretation in Japanese criminal law, a domain governed by the overarching principle of legality (罪刑法定主義 - Zaikyōhōteishugi). This principle, often expressed by the Latin maxims nullum crimen sine lege (no crime without law) and nulla poena sine lege (no punishment without law), dictates that conduct cannot be treated as criminal unless it is clearly proscribed by law, and punishment cannot be imposed unless provided for by law. It serves as a cornerstone of individual liberty, protecting citizens from arbitrary state power.

Within this framework, Japanese courts employ several methods of interpretation:

- Literal Interpretation (文理解釈 - Bunri Kaishaku): This is the starting point, focusing on the ordinary, everyday meaning of the words used in the statute. In W's case, the ordinary meaning of "capture" (hokaku) would generally imply actual success in taking an animal.

- Logical Interpretation (論理解釈 - Ronri Kaishaku): This involves applying logical reasoning to understand the statute, including drawing inferences from its structure and language.

- Systematic Interpretation (体系的解釈 - Taikeiteki Kaishaku): This method requires interpreting a provision by considering its place within the entire statute, its relationship to other provisions in the same law, and its coherence with the broader legal system. The Supreme Court's reference to its interpretation of "capture" in Articles 11 and 15 of the same Act reflects a systematic approach.

- Purposive or Teleological Interpretation (目的論的解釈 - Mokutekironteki Kaishaku): This approach seeks to understand the provision by considering the underlying purpose or objective (telos) the legislature intended to achieve with the law. In W's case, the purpose was the protection and breeding of game birds. The courts leaned heavily on this to justify a broader reading of "capture."

A critical distinction in Japanese penal law interpretation is between permissible extensive interpretation (拡張解釈 - kakuchō kaishaku) and prohibited analogical interpretation (類推解釈 - ruisui kaishaku).

- Extensive interpretation involves stretching the meaning of statutory terms to cover situations that are not explicitly mentioned but can be considered to fall within the "possible meaning of the words" (可能な語義の範囲内 - kanōna gogi no han'inai) when viewed in light of the law's purpose.

- Analogical interpretation, on the other hand, applies a law to a situation that is not covered by its text, even under a broad reading, simply because that situation is similar to one that is covered. This is forbidden in criminal law because it violates the principle of legality – one cannot be punished for an act that the law does not actually proscribe.

The central debate in cases like W's often boils down to whether the court's interpretation is a permissible extensive one or an impermissible analogical one.

The concept of the "protected legal interest" (保護法益 - hogo hōeki) also plays a significant role. This refers to the specific interest or value that a particular criminal provision aims to protect (e.g., life, property, public safety, or, in this case, wildlife populations). Identifying the protected legal interest helps guide the interpretation of the elements of an offense. However, as the supplementary opinion implicitly warns, an overzealous focus on protecting the hogo hōeki should not lead to interpretations that disregard the clear meaning of the statutory text or the rights of the accused. There must be a "feedback loop" or "reciprocal gaze" (視線の往復 - shisen no ōfuku) between literal/logical interpretation and purposive/systematic interpretation.

In W's case, the critical question was whether defining an unsuccessful attempt to shoot a duck as "capture" was a justifiable extensive interpretation, driven by the purpose of wildlife protection, or if it constituted an analogical leap, especially given that "capture" in common parlance implies success.

VIII. The "Capture" Conundrum: Actual Seizure vs. The Act Itself

The heart of the legal dispute was the ambiguity of "capture" (hokaku). As discussed, two main theories existed:

- Actual Capture Theory (現実捕獲説 - genjitsu hokaku setsu): This theory posits that "capture" requires the animal to be actually brought under the hunter's physical control, either by killing it or by otherwise securing it. Under this view, W's actions, which resulted in no ducks being hit or retrieved, would not constitute capture.

- Capture Act Theory (捕獲行為説 - hokaku kōi setsu): This theory argues that the act of attempting to capture, using the means and methods associated with capture, is sufficient to meet the definition, regardless of the outcome. The lower courts and the Supreme Court majority effectively adopted this stance for the specific regulation W was charged under.

The supplementary opinion highlighted a key problem: the term "capture" might not have a consistent meaning even within the same Wildlife Protection Act. For instance, a provision dealing with the illegal sale of captured animals (e.g., Article 20 of the Old Act) would almost certainly refer to animals actually captured (supporting the actual capture theory). Conversely, provisions prohibiting dangerous hunting methods or hunting in protected areas might logically be interpreted to cover the act of hunting itself, regardless of success, to prevent the inherent risks and disturbances those acts create (supporting the capture act theory for those specific contexts).

The everyday Japanese meaning of "捕獲" (hokaku) leans towards "to catch," "to capture alive," or "to seize." An unsuccessful attempt is typically described as "attempted capture" (捕獲未遂 - hokaku misui). At the time of W's actions and judgment, the Old Wildlife Protection Act did not have a general provision criminalizing "attempted capture" for the specific offense W was charged with (i.e., violating a hunting method restriction under Article 1, Section 4, Paragraph 3). The absence of such an "attempt" provision often creates pressure on courts. If judges believe the conduct is blameworthy and falls within the spirit of the law's prohibition, they might be inclined to interpret the "completed" offense more broadly to cover the attempt. However, this is precisely where the danger of crossing into analogical interpretation arises.

IX. Legislative Evolution: The Aftermath and Clarity

The legal discussions and interpretative challenges exemplified by W's case and similar rulings did not occur in a vacuum. They often signal areas where the law may lack clarity or require updating to meet contemporary needs and understandings of justice.

In 2002, the Old Wildlife Protection Act underwent a comprehensive revision, resulting in the current "Law for the Protection and Management of Birds and Beasts and the Optimization of Hunting" (鳥獣の保護及び管理並びに狩猟の適正化に関する法律 - Chōjū no Hogo Oyobi Kanri Narabini Shuryō no Tekiseika ni Kansuru Hōritsu). Significantly, this new, overhauled legislation introduced specific provisions criminalizing "attempt" (未遂 - misui) for certain offenses. For example, Article 83, Paragraph 2 and Article 84, Paragraph 2 of the revised law deal with attempts.

The creation of explicit "attempt" provisions can be seen, in part, as a legislative response to the kinds of interpretative difficulties highlighted in W's case. By explicitly criminalizing attempts for certain acts, the legislature provides a clearer legal basis for prosecution and punishment, reducing the need for courts to stretch the definition of a completed offense to cover preparatory or unsuccessful actions. This aligns better with the principle of legality, ensuring that citizens have clearer notice of what conduct is prohibited.

X. Concluding Thoughts: Law, Language, and Legislative Intent

The 1996 Supreme Court decision in the case of W, involving missed crossbow shots at wild ducks, thus transcends its peculiar facts. It offers a window into the meticulous, often challenging, process of judicial interpretation of penal statutes in Japan. The judgment, especially when read alongside the insightful supplementary opinion, underscores the tension between ensuring that laws effectively protect their intended interests (like wildlife conservation) and the paramount importance of upholding the principle of legality.

The case demonstrates that while purposive interpretation is a valid and necessary tool for understanding and applying the law, it must operate within the bounds of the possible meaning of the statutory language. When the perceived need for regulation extends beyond what the text can reasonably bear, the onus shifts to the legislature to amend the law or enact new provisions. The subsequent evolution of the Wildlife Protection Act, with the introduction of specific clauses for "attempted" offenses, reflects this ongoing dialogue between the judiciary and the legislature in refining the legal framework.

Ultimately, W's case is a reminder that the clarity and precision of statutory language are vital for legal certainty, ensuring that individuals can understand what conduct is criminal and that the state's power to punish is exercised within clearly defined legal boundaries. It highlights the delicate balance that courts must strike in a system that values both the spirit of the law and the letter of the law.