The Duty to Transfer: Japan's Supreme Court on Recognizing Limits and Protecting Patient Chances

Date of Judgment: November 11, 2003 (Heisei 15)

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, 2002 (Ju) No. 1257

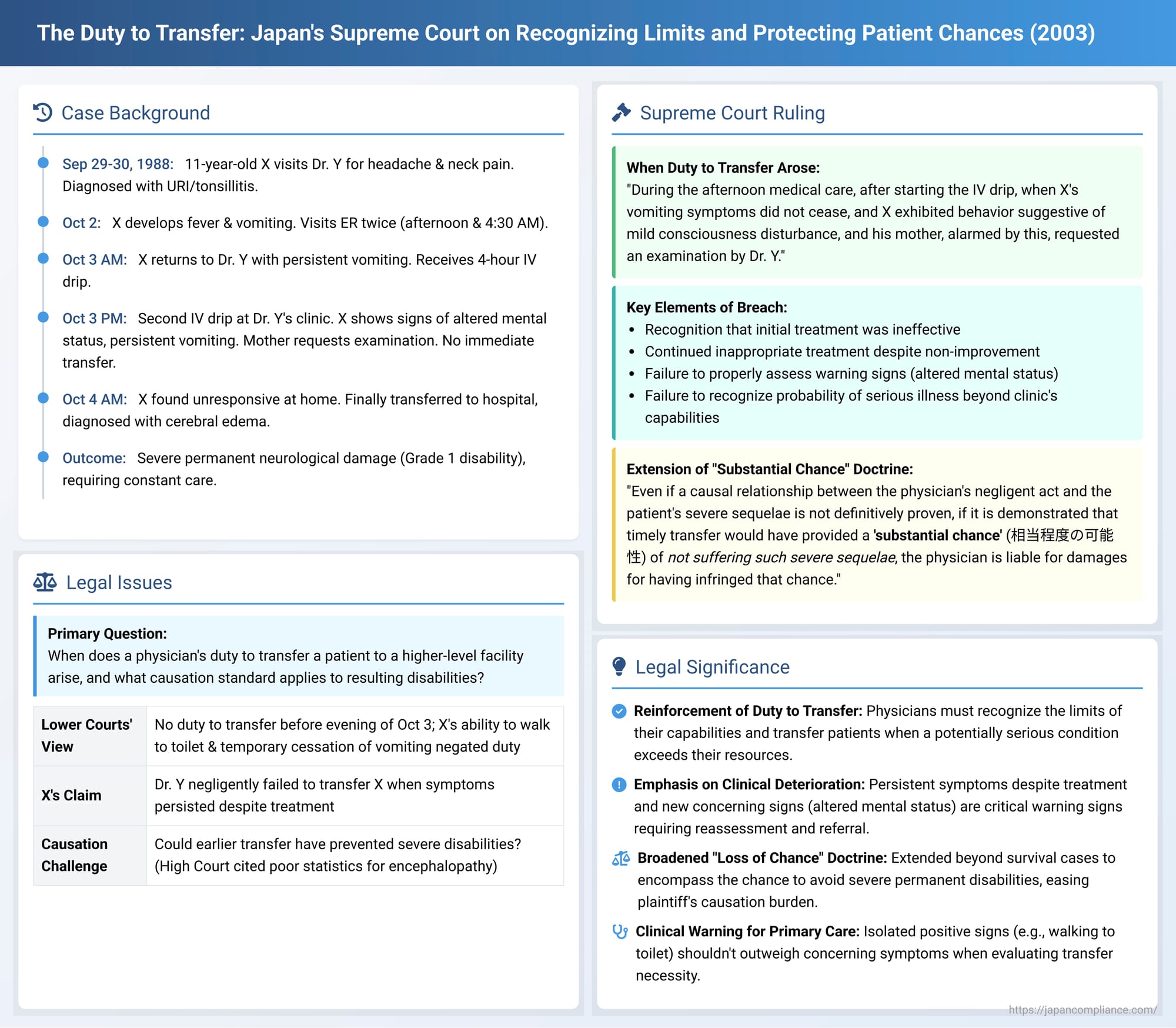

In a significant ruling on November 11, 2003, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed a physician's critical responsibility to recognize the limitations of their own practice and to ensure timely transfer of a patient to a more advanced medical facility when faced with a deteriorating condition that might indicate a serious, unmanageable illness. This case not only reinforced the duty to transfer but also notably applied the "loss of a substantial chance" doctrine to situations involving the potential avoidance of severe, permanent disabilities, extending its reach beyond cases of mortality.

Factual Background: A Child's Worsening Condition and Delayed Recognition

The case involved X, an 11 or 12-year-old elementary school student (6th grade) in 1988 (Showa 63), who had been a regular patient at a clinic operated by Dr. Y, a general practitioner, for about two and a half years.

- Initial Visits (September 29-30, 1988): On September 29, X visited Dr. Y complaining of headache and anterior neck pain. Dr. Y diagnosed an upper respiratory tract infection and right cervical lymphadenitis, prescribing antibiotics, analgesics, and antipyretics. X’s condition did not improve. On September 30, X returned to Dr. Y, who added tonsillitis to the diagnosis, doubled the dosage of antibiotics and analgesics, and instructed X to return on October 3.

- Deterioration and Emergency Room Visit (October 2): From October 2, X developed a fever and complained of nausea. As Dr. Y's clinic was closed (Sunday), X's mother, A, took him to the emergency room of B General Hospital in the afternoon. X received a prescription for an analgesic.

- Escalation (October 2 night - October 3 morning): By 11:30 PM on October 2, X experienced profuse vomiting. Around 4:30 AM on October 3, A took X back to B General Hospital's emergency room. The doctor there diagnosed enteritis, also noting a suspicion of appendicitis, and advised X to consult Dr. Y.

- Third Visit to Dr. Y (October 3, morning): Around 8:30 AM, A took X to Dr. Y's clinic. Dr. Y, after hearing about the visits to B General Hospital, noted X had a 38°C fever and signs of dehydration. He diagnosed acute gastroenteritis and dehydration. X received a 700cc intravenous (IV) drip over approximately four hours in an upstairs treatment room at the clinic. X had to be carried upstairs by his mother. Throughout the IV infusion, X continued to vomit, and his symptoms did not improve. Dr. Y sent X home with instructions to return in the afternoon if the vomiting persisted.

- Fourth Visit to Dr. Y (October 3, afternoon/evening): As X continued to vomit after returning home, A brought him back to Dr. Y's clinic around 4:00 PM. X was again carried upstairs by his mother and received another 700cc IV drip over approximately four hours, until around 8:30 PM.

- During this second IV drip, X's vomiting of yellowish gastric fluid continued. He also made unusual statements, such as saying the first IV bag was the second, and forcefully demanded that the IV be removed. These behaviors suggested a potential alteration in his mental status.

- Alarmed by X's statements and behavior, A requested through a nurse that Dr. Y examine X. Dr. Y, who was busy with outpatient consultations on the first floor, did not immediately attend to X.

- When Dr. Y did examine X (during a break in the IV), he noted dehydration and mild tenderness in the upper left abdomen.

- Around 7:30 PM, X, needing to use the toilet while his mother was briefly absent, managed to move the IV stand and walk to the toilet himself. He reportedly thanked a staff member who handed him a towel.

- After the IV drip finished around 8:30 PM, X was brought downstairs by his mother. During Dr. Y's examination, X was unable to sit on a chair and had to lie down on the examination couch. His temperature had slightly decreased from 37.3°C (before the afternoon IV) to 37.0°C, and his vomiting had temporarily stopped.

- Around 9:00 PM, X was sent home, carried by his mother. Dr. Y, however, considered X's condition potentially serious if the vomiting were to resume. Anticipating the possibility of hospitalization the next day, he prepared a referral letter to a hospital.

- Rapid Decline and Eventual Transfer (October 3 night - October 4): After returning home, X's vomiting resumed, and his fever rose to 38°C. Around 11:00 PM, he complained of distress to his mother. By the early morning of October 4, X was unresponsive to his mother's calls. Dr. Y, concerned about X's condition, telephoned X's home around 8:30 AM, learned of X's state, and instructed A to bring X to the clinic immediately.

- X arrived at Dr. Y's clinic before 9:00 AM, unconscious and unresponsive. Dr. Y recognized the need for emergency hospitalization and decided on C General Hospital, an institution capable of performing detailed examinations and providing inpatient treatment. He gave the previously prepared referral letter to A.

- X was taken to C General Hospital by a family acquaintance. After a wait at reception, he was admitted around 11:00 AM. At admission, he was in a somnolent state, unresponsive, with cold extremities and generalized rigidity.

- Doctors at C General Hospital immediately performed a CT scan, which revealed cerebral edema (brain swelling). Considering X's overall symptoms, they strongly suspected acute encephalopathy, potentially including Reye's syndrome. Treatment to reduce brain pressure (e.g., glycerol, dexamethasone) was initiated immediately.

- Outcome: Despite these efforts, X never regained consciousness. In February 1989, he was diagnosed with acute encephalopathy of unknown cause. The condition left him with severe permanent neurogenic motor dysfunction. He was certified as Grade 1 physically disabled, requiring constant care for all activities of daily living. By May 2001, his mental developmental age was assessed to be around two years old, and he had no language ability. Guardianship proceedings were initiated.

X, through his legal representatives, sued Dr. Y, claiming that the failure to transfer him to a comprehensive medical institution in a timely manner constituted negligence and resulted in his severe permanent disabilities. He sought approximately 68 million yen in damages.

Lower Court Proceedings: Focus on Foreseeability

First Instance (Kobe District Court) and High Court (Osaka High Court):

Both the District Court and the High Court dismissed X's claim. Their reasoning largely centered on the perceived lack of clear indicators that would have compelled Dr. Y to suspect acute encephalopathy earlier. They highlighted the facts that X had walked to the toilet by himself during the afternoon IV on October 3 and that his vomiting had temporarily ceased after the IV infusion concluded. Based on these observations, the lower courts found that Dr. Y did not have a duty to suspect acute encephalopathy or to transfer X to a higher-level facility before the evening of October 3.

The Supreme Court's Decision (November 11, 2003)

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment regarding X's claim against Dr. Y and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Court found that the lower courts had erred in their assessment of both Dr. Y's duty to transfer and the issue of causation.

1. Dr. Y's Duty to Transfer (転送義務 - tensō gimu):

The Supreme Court meticulously reviewed the timeline of X's illness and Dr. Y's interventions, concluding that Dr. Y had indeed breached his duty to transfer X in a timely manner:

- Recognition of Ineffective Initial Treatment: The Court stated that by the time Dr. Y commenced the afternoon IV drip on October 3 (the fourth visit), he should have been capable of recognizing that his initial diagnoses (upper respiratory infection, tonsillitis) and the treatments based on them (antibiotics, doubled medication, morning IV drip) had been ineffective. This was evident from X's lack of any symptomatic improvement and, particularly, the persistent vomiting that had continued since the previous night despite these interventions.

- Inadequate Reassessment and Continued Inappropriate Treatment: Despite the clear signs that the ongoing treatment was not working, Dr. Y proceeded with an identical IV drip in the afternoon, administered in an upstairs treatment room where continuous, close monitoring of X's condition was inherently more difficult.

- Emergence of Clear Warning Signs: During this afternoon IV session, the situation escalated. X's vomiting not only persisted but he also began to exhibit behaviors (confused statements about the IV bag, agitated demands for the IV to be removed) that were strongly suggestive of a mild consciousness disturbance. This, coupled with his mother's expressed anxiety and her request for Dr. Y to examine X, should have been critical warning signs.

- Recognizable Probability of Serious, Urgent Illness: The Supreme Court concluded that at this juncture—when X continued to vomit despite the afternoon IV and displayed signs of altered mental status—Dr. Y should have been able to recognize a high probability that X was suffering from some form of serious and urgent illness. Even if a specific diagnosis (like acute encephalopathy) could not be made with certainty at his clinic, it should have been clear that X's condition was beyond the diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities of his facility.

- Nature of Potential Illnesses (Including Acute Encephalopathy): The Court noted that the category of "serious and urgent illness" compatible with X's symptoms would include conditions like acute encephalopathy. Such conditions are known to have generally poor prognoses, with outcomes heavily dependent on the timeliness and appropriateness of treatment, especially concerning the management of complications like cerebral edema.

- The Point at Which Duty to Transfer Arose: Based on these considerations, the Supreme Court pinpointed the moment Dr. Y's duty to transfer X crystallized: "During the [afternoon] medical care, after starting the IV drip, when X's vomiting symptoms did not cease, and X exhibited behavior suggestive of mild consciousness disturbance, and his mother, alarmed by this, requested an examination by Dr. Y." At that specific point, Dr. Y had an obligation to immediately diagnose X and then transfer him to a medical institution equipped for advanced diagnostics (like CT scans) and inpatient treatment capable of managing severe, urgent conditions including acute encephalopathy.

- Negligence in Failing to Transfer: Dr. Y's failure to take these steps at that critical time constituted negligence. The fact that X later walked to the toilet or that his vomiting briefly stopped after the IV did not negate the duty that had already arisen based on the earlier, more alarming signs.

2. Causation and the "Loss of a Substantial Chance" (相当程度の可能性 - sōtō teido no kanōsei):

The Supreme Court then addressed the issue of causation, applying and extending its "loss of a substantial chance" doctrine:

- Extension of the "Loss of Chance" Doctrine: The Court referenced one of its prior landmark decisions (Supreme Court, September 22, 2000, which dealt with loss of a chance of survival) and explicitly extended this principle to cases involving severe, permanent sequelae, as in X's situation.

- The Principle: "Even if a causal relationship between the physician's negligent act (failure to transfer) and the patient's subsequent severe sequelae is not definitively proven, if it is demonstrated that timely transfer to an appropriate medical institution for proper examination and treatment would have provided a 'substantial chance' (相当程度の可能性 - sōtō teido no kanōsei) of the patient not suffering such severe sequelae, the physician is liable for damages for having infringed that chance."

- Application to X's Case: Dr. Y was found negligent for failing to transfer X in a timely manner. X undisputedly suffered severe, permanent neurological damage. The crucial question, therefore, became whether a timely transfer to a facility like C General Hospital, and the administration of appropriate examinations and treatments there, would have offered X a "substantial chance" of a better outcome (i.e., avoiding the devastating level of disability he ultimately endured).

- Critique of the High Court's Statistical Analysis: The Supreme Court found the High Court's interpretation of the prognostic statistics for acute encephalopathy to be flawed. The High Court had focused on the generally poor overall outcomes (e.g., only a 22.2% complete recovery rate in one study) to conclude that a substantial chance of preventing X's sequelae could not be established. The Supreme Court countered this by pointing out that:

- The determination of a "substantial chance" should be made by considering X's specific clinical condition at the time the transfer should have occurred, and then evaluating the potential impact of timely and appropriate treatment at a higher-level facility.

- The very same statistics cited by the High Court also indicated that a significant proportion of encephalopathy survivors did not end up with the most severe forms of neurological damage. For example, one statistic showed that while 63% of survivors had some CNS sequelae, 37% did not. Another showed that the 77.8% who did not achieve complete recovery would include patients with milder sequelae, not just those as severely affected as X.

- Therefore, these statistics, rather than negating a substantial chance, could actually support the argument that such a chance existed for X to have a less severe outcome had he been transferred and treated earlier.

The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court had erred in its interpretation and application of the law concerning both the duty to transfer and the assessment of a "substantial chance" of avoiding severe sequelae. The case was remanded for the High Court to re-examine these issues, particularly the likelihood of a better outcome for X with timely transfer and appropriate advanced medical care.

Analysis and Implications: Strengthening Patient Protection

The Supreme Court's decision in this 2003 case carries several important implications for medical practice and malpractice law in Japan:

- Reinforcement of the Duty to Transfer: This ruling powerfully reinforces the obligation of physicians, particularly those in primary care or smaller clinic settings, to recognize the limits of their diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities. When a patient's condition is not improving as expected, or when symptoms suggest a potentially serious or complex illness beyond the facility's scope, a timely transfer to a higher-level or specialized medical institution is a critical component of the duty of care.

- Emphasis on Early Recognition of Non-Improvement and Deterioration: The case underscores that physicians must engage in continuous, critical reassessment of their working diagnoses and treatment plans. A failure to respond to initial treatment, or a worsening of symptoms, should trigger a heightened level of vigilance and a readiness to consider alternative diagnoses and management strategies, including referral.

- Broader Application of the "Loss of a Substantial Chance" Doctrine: A very significant aspect of this judgment is its application of the "loss of a substantial chance" doctrine to cases involving the avoidance of severe permanent disabilities, not just the chance of survival. This broadens the scope for patients to obtain compensation when medical negligence deprives them of a realistic opportunity for a better quality of life, even if direct causation of the exact level of harm is difficult to prove with absolute certainty.

- Holistic Assessment of Symptoms Required: The Supreme Court's approach indicates that physicians should not be unduly reassured by isolated positive signs (like X walking to the toilet) if the overall clinical picture, including persistent core symptoms (like intractable vomiting) and new concerning signs (like altered mental status), points towards a serious underlying problem.

- Clear Guidance for Primary Care Physicians: This decision provides important legal guidance for general practitioners and physicians in smaller clinics regarding the threshold for referral. It implies that even without a definitive diagnosis, a strong suspicion of a serious condition that requires resources unavailable at the current facility warrants prompt transfer.

- Facilitating Proof in Complex Cases: The "substantial chance" doctrine can ease the burden of proof for plaintiffs in complex medical cases. While it doesn't eliminate the need for evidence, it allows for recovery when it can be shown that a physician's negligence closed a window of opportunity for a significantly better outcome, even if that better outcome wasn't guaranteed.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's November 11, 2003, judgment significantly advances patient rights in Japan by clarifying the scope of a physician's duty to transfer and by extending the "loss of a substantial chance" doctrine to encompass the possibility of avoiding severe long-term disabilities. It sends a clear message that medical professionals must be vigilant in monitoring patient progress, quick to recognize when their own resources are insufficient, and proactive in facilitating access to higher levels of care when necessary. This ruling underscores the legal system's commitment to ensuring that patients are not deprived of meaningful opportunities for better health outcomes due to failures in timely and appropriate medical referrals.