The Drunken Hand and the Sober Mind: Japan's Foundational Ruling on Self-Induced Intoxication

Decision Date: January 17, 1951

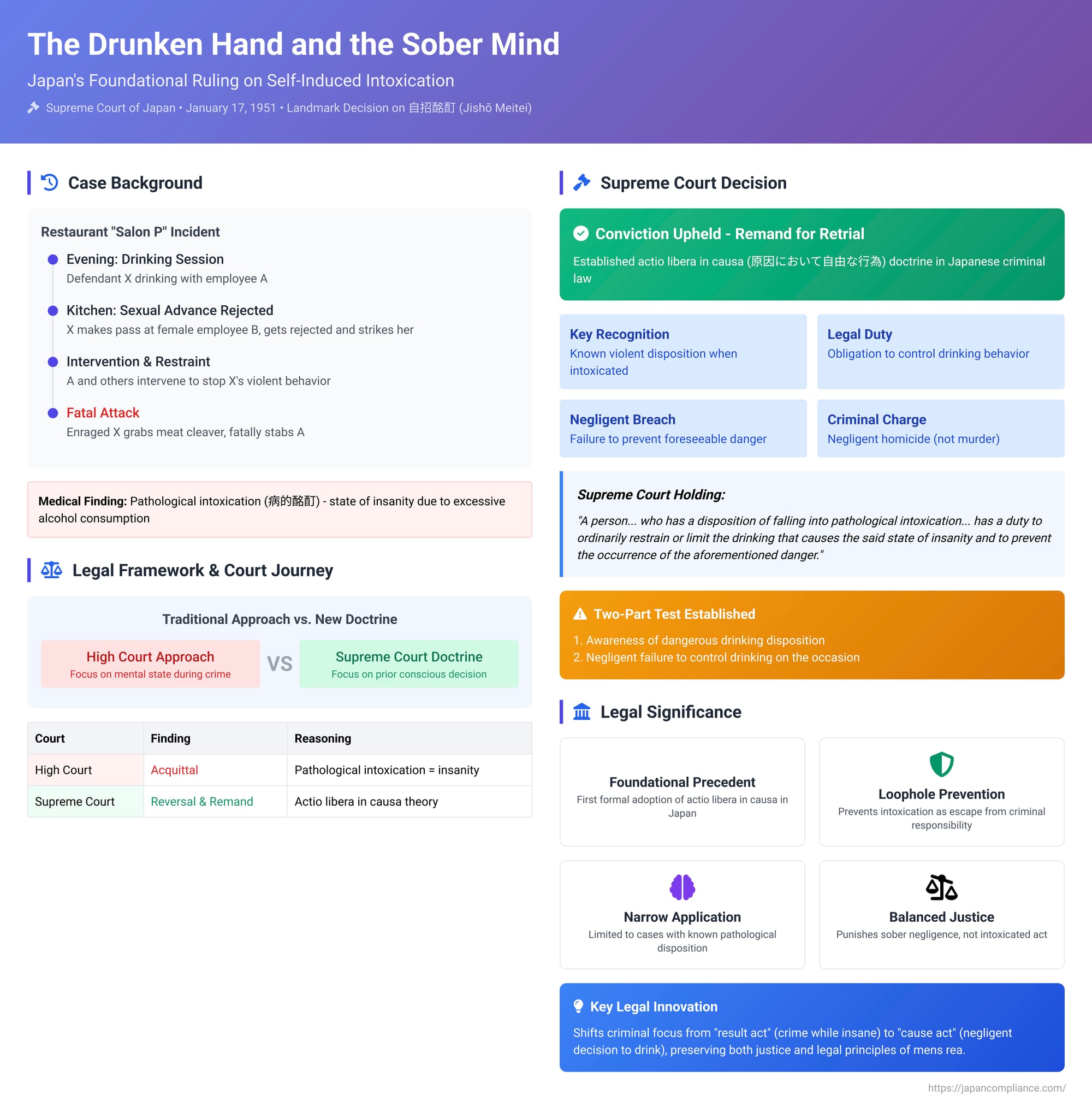

Criminal law grapples with few questions as ancient and as difficult as the intoxicated offender. What legal responsibility does a person bear for a crime committed while so drunk that they lose all sense of right and wrong, or all ability to control their actions? Can a state of voluntary intoxication provide a defense against a charge of murder? On January 17, 1951, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a landmark decision that answered this question by formally introducing a powerful legal doctrine into Japanese jurisprudence: actio libera in causa, or "action free in its cause." The ruling established that a person cannot use a state of self-induced insanity as a shield, creating a framework to trace criminal responsibility back to the sober, conscious decision to drink.

The Factual Background: A Drunken Rage in a Restaurant Kitchen

The incident took place in a restaurant called "Salon P". The defendant, X, had been drinking with a male employee of the establishment, A. Later, in the restaurant's kitchen, X made a pass at a female employee, B. When B rejected his advances, X struck her. His companion, A, and others who were present intervened to restrain X.

Enraged at being stopped, X grabbed a meat cleaver that was lying nearby and, in a sudden outburst, stabbed A. The wound was fatal, and A died immediately from massive blood loss. X was charged with murder.

The Lower Court's Ruling: An Acquittal Based on "Pathological Intoxication"

At the appellate level, the Sapporo High Court heard evidence from a psychiatric expert. Based on this evaluation, the court found that the defendant had an underlying predisposition to mental illness. It concluded that, due to his excessive consumption of alcohol on the day of the crime, he had fallen into a state of "pathological intoxication" (byōteki meitei). At the moment he stabbed A, the court ruled, he was in a state of "insanity" (shinshin sōshitsu)—lacking the mental capacity to be held criminally responsible for his actions. On this basis, the High Court acquitted X of the murder charge.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Intervention: Introducing Actio Libera in Causa

The prosecutor appealed the acquittal to the Supreme Court. The appeal argued that the lower court had erred by failing to consider the defendant's culpability for the act of getting drunk in the first place. The prosecutor asserted that the defendant had a known "violent drunken disposition" (kyōbō na sakeguse) and that he was aware of this trait. This prior knowledge, the prosecutor argued, created a duty for him to control his drinking, a duty he had negligently breached.

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench agreed with the prosecutor's logic. It overturned the acquittal and sent the case back to the lower court for retrial, and in doing so, it established the legal framework for actio libera in causa in Japan.

The New Legal Principle:

The Court declared that a person who knows they have a dangerous predisposition cannot escape liability for crimes committed after voluntarily losing control. It stated:

"A person such as X in this case, who has a disposition of falling into a pathological intoxication when drinking a large amount of alcohol and thereby has a risk of causing criminal harm to others in a state of insanity, has a duty to ordinarily restrain or limit the drinking that causes the said state of insanity and to prevent the occurrence of the aforementioned danger."

A Two-Part Test for Culpability:

The Court then laid out a clear, two-part test for finding criminal liability in such cases. The lower court was instructed to determine:

- Whether the defendant was aware of his own disposition to become dangerously violent when he drank to excess.

- Whether the fatal stabbing occurred as a result of his negligent failure to uphold his duty to control his drinking on that specific occasion.

If both conditions were met, the Supreme Court held, the defendant "cannot escape responsibility for negligent homicide."

A Deeper Dive: The Doctrine of "Action Free in its Cause" in Japanese Law

This 1951 decision is foundational because it provided a solution to a potential loophole in the law. Without this doctrine, a person could, in theory, negligently or even intentionally become intoxicated to the point of legal insanity and then be acquitted for any crime they commit in that state. Actio libera in causa (or, in Japanese, gen'in ni oite jiyū na kōi) closes this loophole by shifting the focus of legal blame from the "result act" (the crime committed while incapacitated) to the earlier "cause act" (the free and voluntary act of becoming incapacitated).

The "Cause Act" as the Crime:

The dominant understanding of this doctrine in Japan is that the legally culpable act is the cause act. The defendant is not punished for the stabbing he committed while insane, but for the negligent act of drinking to excess, knowing the potential for a violent outcome. The insane act is treated merely as a link in the causal chain that connects the negligent drinking to the final result of death.

Why Negligent Homicide and Not Murder?

A crucial aspect of the Supreme Court's ruling is its conclusion that the appropriate charge would be negligent homicide (kashitsu chishi), not murder. This is because, in cases like this where the intent to kill arises only after the defendant has lost their mental capacity, the law can only hold them responsible for the mental state they possessed at the time of the cause act. When X began drinking, he had no intention of killing A. Therefore, he cannot be convicted of an intentional crime like murder. However, if he knew that his drinking created a foreseeable risk that he might violently harm or kill someone, his act of drinking was negligent with respect to that risk. This logic has been consistently applied in subsequent Japanese cases involving crimes committed under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

A Narrow and Exceptional Doctrine:

It is important to note how narrowly the Supreme Court tailored this doctrine. The test requires not just that a person got drunk and committed a crime, but that they have a specific "disposition" to fall into a state of pathological intoxication and cause harm, and that they are aware of this specific, dangerous predisposition. This is a very high bar. The ruling does not mean that anyone who gets into a bar fight while drunk can be charged with negligent homicide under this theory. The doctrine is reserved for exceptional cases where a defendant has a known, almost medical, condition that makes their intoxication uniquely and foreseeably dangerous.

Conclusion: Punishing the Cause, Not Just the Act

The Supreme Court's 1951 ruling is a cornerstone of Japanese criminal law, providing a clear and logical framework for assigning responsibility for crimes committed during a state of self-induced incapacity. By establishing the doctrine of actio libera in causa, the Court ensured that the insanity defense could not be used as a shield by those who voluntarily and culpably relinquish control of their actions.

The decision masterfully balances two competing legal principles. On the one hand, it prevents offenders from escaping justice. On the other, by limiting the potential charge to a crime of negligence rather than intent, it upholds the fundamental principle of culpability—that a person can only be held responsible for the mental state they possessed at the time they were acting as a free and conscious agent. It punishes the sober mind for its negligent choices, not the drunken hand for the acts it can no longer control.