The Domino Effect: How a Non-Existent Director Election Can Topple Subsequent Appointments in Japanese Corporate Law

Case: Action for Confirmation of Status, etc.

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of April 17, 1990

Case Number: (O) No. 1529 of 1985

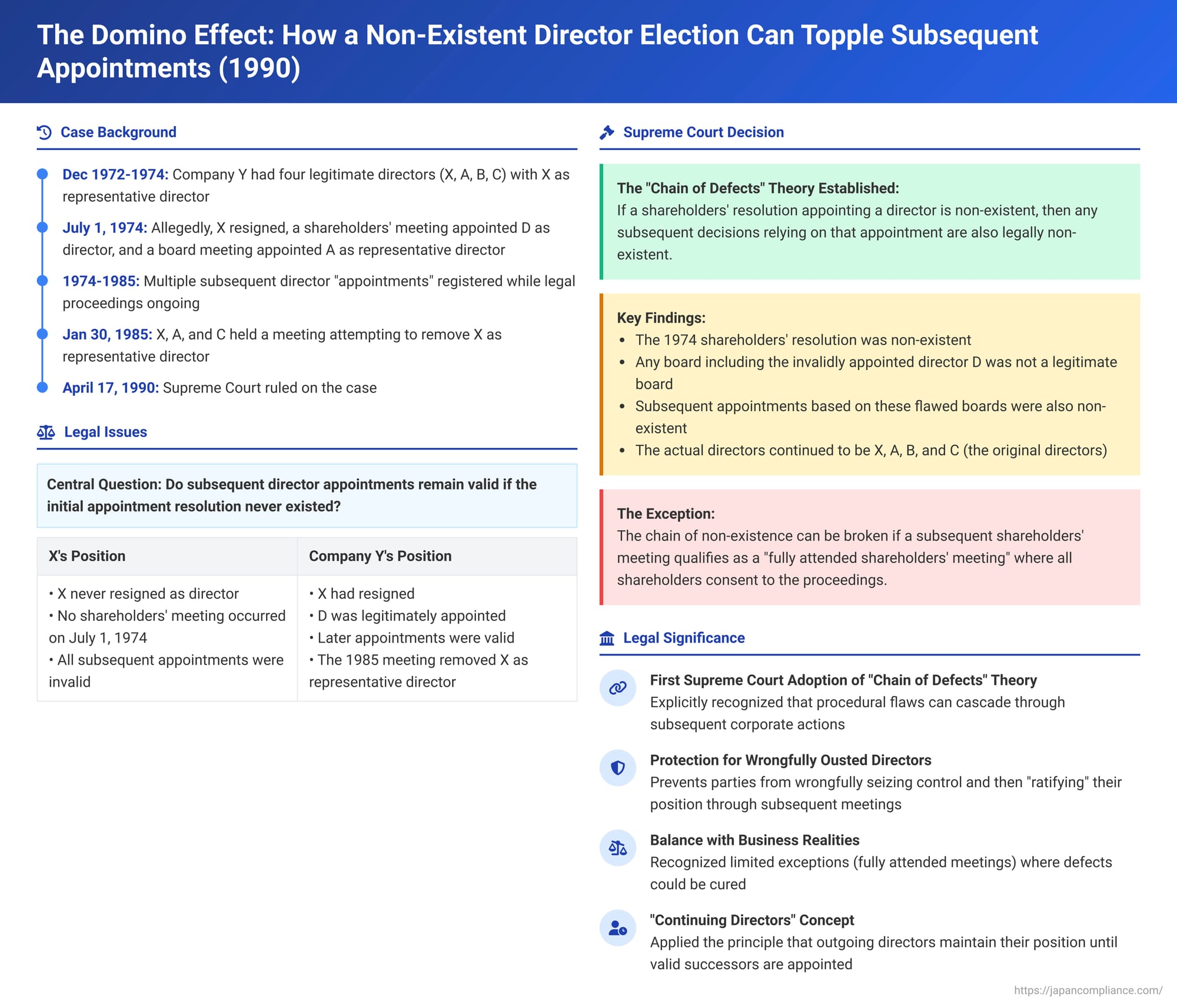

In the often-turbulent world of closely-held corporations, disputes over control can lead to complex legal battles. A critical question that can arise is: what happens if a resolution appointing a director is found to have never actually existed? Can subsequent director appointments, made by a board relying on that initial flawed "appointment," stand? A pivotal Japanese Supreme Court decision on April 17, 1990, addressed this head-on, establishing and applying the "chain of defects" (kashi rensa) theory, demonstrating how an initial void in corporate governance can cascade through subsequent actions.

The Spark of the Dispute: A Contested Directorship in Company Y

The case revolved around Company Y, a company whose issued shares (4,000 in total) were split equally between X and her husband, A. This equal split unfortunately fostered a control dispute.

As of June 30, 1974, the legitimate directors of Company Y were X, A, B, and C. X was also the representative director. Their two-year terms, having commenced on December 25, 1972, were due to expire on December 25, 1974.

The trouble began with events purported to have occurred on July 1, 1974:

- A letter of resignation from X as a director was allegedly created.

- Minutes of a supposed extraordinary shareholders' meeting were drafted, stating that D was appointed as X's replacement director.

- Minutes of a supposed board of directors' meeting were also created, claiming A was appointed as the new representative director.

- These changes were subsequently registered in Company Y's commercial登記簿 (company registry).

X vehemently denied these events. She asserted that she had never resigned and that neither the shareholders' meeting nor the board meeting on July 1, 1974, had actually taken place. The resolutions recorded were, in her view, entirely non-existent. Consequently, X filed a lawsuit against Company Y seeking:

- Confirmation of her status as a director and representative director of Company Y.

- Confirmation that A did not hold the status of representative director.

- Confirmation of the non-existence of the shareholders' resolution supposedly appointing D as a director.

The court of first instance (Nagoya District Court, judgment dated September 25, 1981) ruled entirely in X's favor, validating her claims. Company Y appealed this decision.

Escalating Actions and a Controversial Board Meeting

While the legal proceedings were ongoing, the faction represented by A continued to operate Company Y as if their version of events was legitimate. Further director "appointments" were registered in 1978 and 1981. Then, on January 31, 1984, new registrations indicated that A, C (one of the original directors), and D (the director whose 1974 appointment X contested) had assumed office as directors, with A as the representative director.

A crucial event occurred while the appeal was pending before the High Court. A and C, ostensibly acting as directors, requested X to convene a board of directors' meeting. Their stated purpose was to address the directorship situation in light of X's ongoing lawsuit – specifically, if X's claims about her continued directorship were upheld, they intended to remove her as representative director and appoint a new one.

X complied and sent out convocation notices for a board meeting to A and C. However, no notice was sent to B, who was one of the original four directors from 1974. On January 30, 1985, X, A, and C gathered for this board meeting. In the meeting, X was excluded from voting on a motion concerning her status as a "specially interested person." A resolution was then passed to remove X as the representative director and to appoint A in her place. Company Y argued before the High Court that this 1985 board resolution rendered X's claim for confirmation of her representative director status moot.

The appellate court (Nagoya High Court, judgment dated September 11, 1985) dismissed Company Y's appeal. Regarding the January 30, 1985 board meeting, the High Court reasoned that, based on the company registry at that time, the directors of Company Y were A, C, and D. Therefore, a meeting attended by X, A, and C could not be considered a legitimate board meeting of Company Y, and consequently, the resolutions passed at this meeting were non-existent. Company Y further appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Intervention: Unraveling the Chain

The Supreme Court delivered a nuanced judgment:

- X's Director Status: The Court upheld the High Court's decision confirming X's status as a director. The appeal by Company Y on this point was dismissed. The reasoning was that X had never resigned. Her original term as director expired on December 25, 1974. As the company would then have fewer than the prescribed number of directors, X, along with the other legitimately appointed directors (A, B, and C), continued to hold the rights and obligations of directors pursuant to Article 258, Paragraph 1 of the former Commercial Code (a provision similar to Article 346, Paragraph 1 of the current Companies Act) until new directors were validly appointed. X also continued to hold the rights and duties of a representative director under the same principle.

- X's Representative Director Status / A's RD Status: The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's decision on these points and remanded this part of the case back to the Nagoya High Court for further hearing.

- Other Claims: The appeal concerning other claims was dismissed due to lack of grounds.

The Supreme Court's Reasoning: The "Chain of Defects" Theory

The Supreme Court's core reasoning revolved around the "chain of defects" (kashi rensa) originating from the non-existent 1974 resolution:

- Non-Existence of the Initial "Appointment": The Court affirmed the lower courts' findings that the purported shareholders' meeting resolution of July 1, 1974, to appoint D as a director was, in fact, non-existent. No such meeting or resolution had actually occurred.

- The Domino Effect: The Court then laid out the critical "chain of defects" principle:

- If a shareholders' resolution purporting to appoint a director is non-existent, then any board of directors purportedly constituted by including such a non-appointed individual cannot be considered a legitimate board.

- Consequently, any representative director "appointed" by such an improperly constituted and illegitimate board is not validly appointed. (The Court also noted that, in this case, the 1974 board resolution appointing A as RD was itself found to be non-existent by the lower courts. )

- A board of directors and/or a representative director that is not legitimately constituted or appointed does not possess the legal authority to convene a shareholders' meeting.

- Therefore, any resolution passed at a shareholders' meeting that was convened based on a decision by such an unauthorized board, or by such an unauthorized representative director, to appoint new directors, is itself legally non-existent.

- The Exception to Break the Chain: This chain of non-existence can be broken. The Court acknowledged an exception: if a subsequent director appointment resolution is made at a shareholders' meeting that qualifies as a de facto fully attended shareholders' meeting (zen'in shusseki sōkai)—where all shareholders are present and consent to the proceedings, effectively curing any convocation defects—then such a resolution could be valid. This refers to a principle established in a previous Supreme Court case (December 20, 1985).

- Application to Company Y's Subsequent "Appointments": In X's case, Company Y had not argued or provided evidence that any of the subsequent director "appointments" (in 1978, 1981, or 1984) occurred at such a fully attended shareholders' meeting that could cure the original defect. Therefore, the chain of non-existence continued, rendering these interim "appointments" legally non-existent.

- The Legitimate Directors in 1985: As a result of this unbroken chain of defects, the Supreme Court concluded that, as of January 30, 1985 (the date of the contested board meeting), the individuals who continued to hold the rights and duties as directors of Company Y (under Article 258, Paragraph 1 of the former Commercial Code) were the original four from 1974: X, A, B, and C.

- Validity of the January 30, 1985 Board Meeting: This finding led to a crucial reassessment of the 1985 board meeting. This meeting was attended by X, A, and C – three of the four legitimate directors. The resolution passed at this meeting (to remove X as representative director and appoint A) could potentially be valid, despite the failure to notify the fourth legitimate director, B.

The Court referred to another precedent (a Supreme Court judgment of December 2, 1969), which established that a board resolution might still be valid even if a director was not notified, provided that "special circumstances" exist. Such circumstances would be where the unnotified director's attendance and participation would not have changed the outcome of the resolution.

Because the High Court had incorrectly determined the legitimate directors in 1985 and thus wrongly concluded the 1985 board meeting was simply not a board meeting of Company Y, it had failed to examine whether such "special circumstances" existed regarding the non-notification of B. This was the reason for remanding the issue of X's and A's representative director status back to the High Court for further deliberation on the validity of the 1985 board resolution.

Analysis and Implications: Solidifying the "Chain of Defects"

The 1990 Supreme Court judgment is a landmark decision for several reasons:

- First Supreme Court Adoption of "Chain of Defects": It was the first clear instance of the Japanese Supreme Court explicitly adopting and applying the "chain of defects" theory (kashi rensa setsu) to director appointment resolutions. This theory posits that an initial severe defect, like the non-existence of a resolution, can systematically invalidate subsequent actions that depend on the flawed first step.

- Types of "Non-Existence": The concept of a "non-existent resolution" can cover two scenarios:

- Physical Non-Existence: Where no meeting was actually held, or no resolution was made, despite fraudulent records suggesting otherwise. The 1974 resolution appointing D in this case appears to fall into this category.

- Legal Non-Existence (or Nullity Due to Grave Defects): Where a meeting of sorts might have occurred, but the defects in its convocation or procedure are so egregious that the law does not recognize it as a valid resolution.

- Scope of the Doctrine: The judgment specifically addressed the impact of a non-existent director appointment resolution on subsequent director appointment resolutions. The commentary associated with this case suggests its direct reach might be limited to this context. For other types of corporate actions taken by improperly appointed directors that affect third parties, other legal doctrines like de facto director liability or principles of apparent authority might come into play to ensure commercial stability and protect those who relied on the company's outward representations.

- Resolving Conflicting Lower Court Precedents: Prior to this ruling, lower courts in Japan had been divided. Some had applied a similar chain of defects logic, while others had resisted it, often citing concerns for legal stability and arguing that later, procedurally correct resolutions should stand on their own. This Supreme Court decision provided much-needed clarity.

- Protecting Wrongfully Ousted Shareholders/Directors: A key rationale behind supporting the chain of defects theory, particularly in internal corporate disputes within closely-held companies, is the protection of individuals like X who might be unjustly stripped of their positions through fraudulent or grossly improper means. Without this doctrine, a party could wrongfully seize control, and then use that control to "ratify" their position through subsequent, albeit defectively convened, meetings, leaving the ousted party with little recourse if the litigation drags on.

- The Role of "Continuing Directors": The Court’s application of Article 258, Paragraph 1 of the former Commercial Code (now Article 346, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act) was crucial. This provision ensures that when directors' terms expire and new ones are not yet validly appointed (or if the number of directors falls below the statutory minimum), the outgoing directors continue to hold their rights and responsibilities. This provided a baseline of legitimate directors (X, A, B, and C) for Company Y, preventing a complete governance vacuum once the subsequent "appointments" were deemed non-existent.

- "Special Circumstances" for Excusing Board Notice Defects: The remand concerning the 1985 board meeting highlights another important nuance: defects in board meeting procedures (like failure to notify a director) are not always fatal. If it can be convincingly shown that the absent director's participation would not have altered the resolution's outcome, the resolution may stand. The factors considered include the absent director's likely stance on the issue and their overall influence on the board.

- Academic Discourse: Before this judgment, many legal scholars were hesitant about the broad application of a chain of defects theory due to its potential to destabilize corporate affairs. They proposed alternative theories to limit its impact, such as using principles of estoppel based on false entries in the commercial register, denying the retroactive effect of resolution annulments, or broadly applying the de facto director doctrine. However, particularly for internal disputes within smaller, closed companies where third-party reliance is less of an issue, the chain of defects theory gained more acceptance as a tool for achieving substantive justice, a trend supported by this ruling.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's April 17, 1990, decision profoundly impacted Japanese corporate law by formally endorsing the "chain of defects" theory in the context of non-existent director appointment resolutions. It establishes that a fundamentally flawed or non-existent initial step in appointing corporate leadership can indeed topple a series of subsequent appointments that rely upon it. While this principle is critical for rectifying internal corporate wrongs and protecting the rights of legitimate shareholders and directors, the Court also acknowledged that the chain is not unbreakable—a de facto fully attended shareholders' meeting can cure prior convocation defects. Furthermore, even when the correct set of directors is identified, defects in their own subsequent board meetings must be assessed for their actual impact on resolutions. This judgment provides a framework that seeks to balance the need for legitimate corporate governance with mechanisms to prevent perpetual invalidity where defects can be, or are effectively, cured.