The Doctor's Duty: A 1912 Japanese Apex Court Ruling on Examining Physician Negligence and Life Insurance Disclosure

Judgment Date: May 15, 1912

Court: Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation), Second Civil Department

Case Name: Claim for Insurance Money

Case Number: Meiji 45 (O) No. 46 of 1912

Introduction: The Delicate Balance of Disclosure in Life Insurance

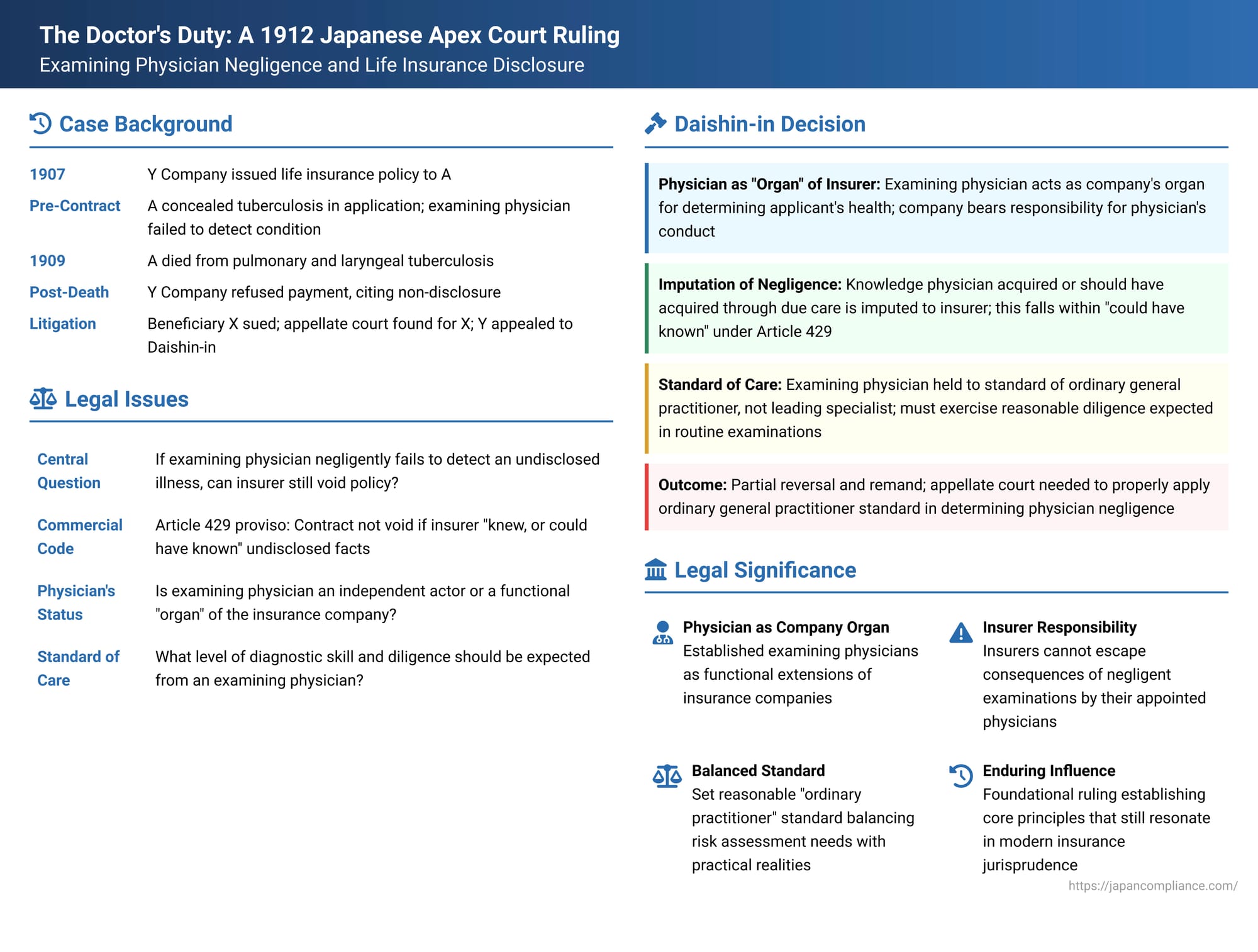

The foundation of any life insurance contract rests upon the principle of utmost good faith, particularly concerning the applicant's duty to disclose material facts about their health and medical history. This information is vital for the insurer to accurately assess the risk it is undertaking and to determine the appropriate terms and premium for the policy. A failure by the applicant to disclose such "material facts" (重要ナル事実 - jūyō naru jijitsu) could, under the insurance laws of the early 20th century in Japan, render the insurance contract void.

However, the process of obtaining life insurance often involves a medical examination conducted by a physician appointed or commissioned by the insurance company. This raises critical questions: What is the legal status of this examining physician (診査医 - shinsai)? If an applicant conceals a pre-existing medical condition, but the insurer's own examining physician, through a lack of ordinary care, fails to discover that condition during the examination, can the insurer still void the policy for non-disclosure? Or is the physician's negligence in failing to detect the condition imputed to the insurance company, effectively meaning the insurer "could have known" the undisclosed facts and thus lost its right to void the contract? Furthermore, what is the appropriate standard of care to which such an examining physician should be held? These fundamental questions were addressed by the Daishin-in, Japan's highest court at the time, in a landmark decision in 1912.

The Facts: Undisclosed Tuberculosis and a Denied Life Insurance Claim

The case involved a life insurance policy issued by Y Life Insurance Company on October 20, Meiji 40 (1907), insuring the life of Mr. A. The beneficiary of the policy was Mr. X (the plaintiff in the subsequent lawsuit). It is unclear from the judgment summary who the original policyholder was, but the focus is on Mr. A as the insured life.

Tragically, on January 21, Meiji 42 (1909), Mr. A died. His cause of death was identified as pulmonary and laryngeal tuberculosis ("the subject illness"). When Mr. X, as the beneficiary, made a claim for the insurance proceeds, Y Life Insurance Company refused payment. The insurer asserted that the insurance contract was void from its inception because, at the time the policy was applied for, Mr. A had failed to disclose that he was suffering from the subject illness. This non-disclosure, Y Company argued, constituted a breach of the duty of disclosure regarding material facts, as stipulated by Article 429 of Japan's (then-applicable, pre-1911 amendment) Commercial Code. Under that version of the law, such a breach rendered the insurance contract void.

The Core Legal Issues Before the Daishin-in

The case presented several critical legal questions for the Daishin-in to resolve:

- Status and Responsibility of the Insurer's Examining Physician: What is the legal relationship between an examining physician and the insurance company that appoints or commissions them? Is the physician an independent actor, or do they function in some capacity as a representative or "organ" of the insurer for the purpose of assessing the applicant's health?

- Imputation of Physician's Knowledge or Negligence: If an examining physician, through their own negligence or lack of due care, fails to discover a pre-existing medical condition that an applicant has not disclosed, can this negligence be imputed to the insurance company? Specifically, does this mean the insurer falls under the proviso of the then-Commercial Code Article 429, which stated that the contract would not be void if the insurer knew, or could have known (知ルコトヲ得ヘカリシ - shiru koto o u-bekarishi), the undisclosed material facts?

- Standard of Care for an Examining Physician: What level of medical skill and diligence is an insurer's examining physician expected to exercise during a pre-insurance medical assessment? Are they held to the standard of a top specialist, or to a more general standard of medical practice?

The Lower Court's Ruling

The Tokyo Court of Appeal (the "original judgment" from which the appeal to the Daishin-in was made) had found in favor of Mr. X, the beneficiary. While it acknowledged that Mr. A had indeed breached his duty of disclosure by not revealing his tuberculosis, the appellate court held that the insurance contract was nonetheless valid. Its reasoning was that Y Company's examining physician could have discovered the illness during the medical examination. Therefore, the appellate court concluded, the insurer (Y Company) was in a position where it "could have known" the undisclosed facts, thereby triggering the statutory proviso that prevented the contract from being voided. Y Life Insurance Company appealed this decision to the Daishin-in, arguing, among other points, that an examining physician's ability to potentially discover a condition did not automatically mean the insurer itself "could have known" it in a legal sense, and that the illness in question was not necessarily something the physician should have been expected to find.

The Daishin-in's Decision (May 15, 1912): Physician as Insurer's "Organ"; Negligence Imputable, but Standard of Care is Key

The Daishin-in, in its 1912 judgment, partially reversed the appellate court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. While it agreed with some fundamental principles regarding the physician's role, it found potential flaws in how the standard of care might have been applied or how the facts were assessed by the lower court.

I. The Examining Physician as an "Organ" of the Insurance Company

The Daishin-in first laid down a crucial principle regarding the status of the examining physician:

- It stated that life insurance companies, engaging in a business that has such a significant bearing on the physical well-being of individuals, have an inherent duty arising from the very nature of their business. This duty is to establish and utilize necessary means to ascertain an applicant's health status to determine whether it is appropriate to conclude an insurance contract.

- The examining physician, whether a direct employee of the insurance company or an independent medical professional commissioned by the insurer for the purpose of conducting pre-insurance medical assessments, acts in this process as an "organ of the insurer" (保険者ノ機関 - hokensha no kikan).

- The Court reasoned that the physician's role is to supplement the insurer's own lack of specialized medical knowledge and to enable the insurer to obtain the necessary understanding of an applicant's health condition for the purpose of making an informed underwriting decision. In this capacity, the examining physician effectively functions as an instrument or arm of the insurer for knowing the applicant's health.

- From this characterization, the Daishin-in drew a critical legal consequence: any negligence committed by the examining physician in the course of conducting the health diagnosis or examination has its legal effect against the insurance company itself. Matters that the physician knew, or through the exercise of due care could have known, are to be treated in law as matters that the insurer (the principal) itself knew or could have known. The insurance company, having chosen to utilize the physician for this essential underwriting function, must bear responsibility for the physician's professional conduct in carrying out that function.

- Therefore, the Court concluded, even if Y Life Insurance Company itself (e.g., its administrative or underwriting departments) did not have direct knowledge of Mr. A's pre-existing tuberculosis, if its appointed examining physician knew of the condition, or negligently failed to discover a condition that they should have discovered with due care, Y Company could not escape responsibility for that knowledge or negligent lack of knowledge.

II. The Scope of "Facts the Insurer Could Have Known" Under the Commercial Code Proviso

The Daishin-in then addressed the interpretation of the proviso in the former Commercial Code Article 429. This proviso stated that an insurance contract would not be void due to non-disclosure of material facts if the insurer "knew, or could have known them" (其事実ヲ知リ又ハ之ヲ知ルコトヲ得ヘカリシトキ - sono jijitsu o shiri matawa kore o shiru koto o u-bekarishi toki).

- The Court interpreted the phrase "could have known them" to refer to situations where the insurer, despite the applicant's concealment or misstatement of facts, had the opportunity to discover the true state of affairs but failed to do so due to a lack of reasonable care on its part. In other words, it pointed to negligence on the part of the insurer (including its examining physician acting as its organ) in not discovering the undisclosed facts.

- The Daishin-in explicitly stated that the scope of "facts the insurer could have known" is not limited to only those facts that are generally prominent in trade or matters that an insurer should ordinarily foresee in the general course of its business.

- It held that this category includes facts that pertain specifically to the insured person's own body and health status. Although such personal health facts might not be foreseeable by the general public, the insurer, at the time of considering an application for life insurance, is required to take the necessary and appropriate care to learn about them. If the insurer (through its physician) fails to exercise this requisite duty of care and, as a result, does not discover material health facts that should have been uncovered, then those facts fall within the scope of what the insurer "could have known."

- Since a life insurer has a duty to employ or commission examining physicians for this very purpose of ascertaining an applicant's health, and since (as established in Part I) the insurer is responsible for its physician's negligence in conducting these examinations, the Court concluded: if an applicant conceals a pre-existing medical condition, but the insurer's examining physician could have discovered that condition through the exercise of due care but failed to do so because of their own insufficient attention or skill, then this constitutes a "fact the insurer could have known" under the meaning of the statutory proviso. In such a scenario, the proviso would apply, and the insurer would be precluded from voiding the contract based on that non-disclosure.

- The Daishin-in thus found that the lower appellate court was correct, in principle, to consider whether Y Company's examining physician could have discovered Mr. A's tuberculosis as the relevant standard for determining whether the proviso to Article 429 applied.

III. The Standard of Care Expected of an Insurer's Examining Physician

Having established that the examining physician's negligence could be imputed to the insurer and could prevent the insurer from voiding the policy, the Daishin-in then turned to define the level of care that is expected from such a physician:

- The Court stated that it would be contrary to ordinary commercial understanding and practice to demand of an insurer's examining physician the extraordinary level of diagnostic skill, attention, and access to advanced facilities that might be expected of a renowned medical specialist or a leading expert in a particular field of medicine.

- The insurer's general duty, in conducting its business and assessing risks, is to take "ordinary general care" that is appropriate to the current state of medical science and practice at the time. It is not required to provide or utilize every conceivable advanced diagnostic facility or the highest level of specialized expertise for every single insurance applicant.

- Consequently, the examining physician appointed or commissioned by the insurer also need not be a top-tier specialist in all fields. They must, however, possess the skill, competence, and diligence of an ordinary general medical practitioner who is reasonably capable of conducting routine health examinations for patients.

- Therefore, whether an insurer's examining physician was negligent in failing to discover a pre-existing condition during a pre-insurance medical assessment should be judged by the standard of whether they, through a lack of reasonable attention or skill, overlooked symptoms or conditions that an ordinary general practitioner, exercising the level of care customary in such examinations, would normally be expected to discover. The physician (and, by imputation, the insurer) cannot be held to a standard of care higher than this.

Application to Mr. A's Case and the Reason for Remand

In applying these principles to the specific appeal before it:

- The Daishin-in noted that Y Life Insurance Company (the appellant insurer) had argued that the lower appellate court had, in effect, held its examining physician to an unfairly high standard of care, thereby too readily concluding that the physician "could have known" about Mr. A's tuberculosis simply because the condition existed.

- The Daishin-in agreed with the legal principle that the standard of care applicable to the examining physician is that of an ordinary general practitioner.

- However, upon reviewing the lower court's judgment, the Daishin-in found that while the lower court had referred to expert testimony (from a Dr. S F) and had concluded that Y Company's examining physician, with the exercise of "due care," could have discovered Mr. A's tubercular condition, the lower court's judgment did not make it sufficiently clear precisely how it had applied this standard of an ordinary general practitioner's care. It was not entirely evident from the lower court's reasoning whether its finding that the physician "could have known" was based on a proper application of this standard or whether it had implicitly (and incorrectly) demanded a higher level of diagnostic acumen.

- The Daishin-in also found that the lower court's reasoning concerning other alleged non-disclosures by Mr. A (specifically, a history of bronchitis and otitis media, which were raised in the insurer's appeal arguments in the full judgment text) was flawed. The lower court had too readily dismissed these as non-material simply because their "cause was unclear" or because they were not the direct cause of Mr. A's ultimate death. The Daishin-in reiterated its broader definition of materiality – that materiality depends on whether the condition itself, regardless of its immediate cause or its role in the final cause of death, would affect an insurer's assessment of the life risk. It stated that conditions like bronchitis, unless proven to be utterly trivial, are generally presumed to be material, and the burden of proving their non-materiality would fall on the party asserting it (i.e., the claimant).

Due to these perceived deficiencies in the lower appellate court's reasoning, particularly concerning the clear application of the correct standard of care for the examining physician in relation to the discovery of the tuberculosis, and its overly narrow interpretation of materiality for other disclosed/undisclosed conditions, the Daishin-in concluded that the lower court's judgment could not be upheld in its entirety. It therefore reversed the part of the original judgment concerning the insurer's liability and remanded the case to the Tokyo Court of Appeal for a new trial and judgment, instructing it to apply the legal principles as clarified by the Daishin-in.

Analysis and Broader Implications of this Very Early Ruling

This 1912 Daishin-in decision, despite being rendered over a century ago, stands as a foundational judgment in Japanese life insurance law. It was one of the earliest attempts by Japan's highest court to grapple with the complex issues surrounding the duty of disclosure, the role and responsibilities of medical examiners appointed by insurers, and the legal consequences of negligence in the pre-contractual medical assessment process.

1. Establishing the Examining Physician as an "Organ" of the Insurer with Imputed Knowledge/Negligence:

A key and lasting contribution of this judgment was its characterization of the examining physician, when conducting a medical assessment for an insurer, as effectively acting as an "organ" of that insurer. This legal construction had profound implications: it meant that the physician's actions, their knowledge, and, most significantly for this case, their negligence in performing the examination, could be legally imputed to the insurance company. This principle was crucial for establishing a basis for insurer responsibility in the underwriting process that was conducted through these medical professionals.

2. Defining "Could Have Known" in the Context of Insurer Negligence in Disclosure Cases:

The ruling provided an important early interpretation of the statutory proviso in the (then-existing) Commercial Code that prevented an insurer from voiding a policy for non-disclosure if the insurer "knew, or could have known" of the undisclosed material facts. The Daishin-in firmly linked the "could have known" part of this proviso to a failure by the insurer (including its examining physician acting as its organ) to exercise necessary and reasonable care in discovering facts relevant to the risk. In essence, if the insurer was negligent in not discovering the undisclosed material facts, it "could have known" them and would lose its right to void the policy.

3. Setting a Standard of Care for Insurer's Examining Physicians:

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of this case in practical terms is its articulation of the standard of care expected from an insurer's examining physician. The Daishin-in established that this standard is that of an ordinary general medical practitioner. Examining physicians are not expected to possess the extraordinary skills or diagnostic capabilities of leading specialists in every conceivable medical field, nor are insurers required to provide the most advanced diagnostic facilities for every routine pre-insurance examination. However, the physician must exercise the level of attention, skill, and competence that a typical general practitioner would be expected to apply when conducting a health examination for similar purposes. If they fail to detect a condition that an ordinary general practitioner, exercising such reasonable care, should normally have discovered, that failure can constitute negligence, and this negligence can be imputed to the insurance company.

4. Attempting to Balance the Insurer's Need for Information with Practical Realities and Fairness:

The judgment reflects an early attempt by Japan's highest court to strike a fair balance. While it strongly upheld the fundamental importance of the insured's duty to make full and truthful disclosure of material facts, it also recognized that the insurer, particularly when it undertakes a medical examination through its own appointed physician, also bears a responsibility to conduct that examination with a reasonable degree of care. It implicitly acknowledged that insurers cannot entirely shift the burden of risk assessment onto the applicant if their own risk assessment processes (including the medical examination) are negligently performed. The standard of an "ordinary general practitioner" was an attempt to set a realistic and achievable benchmark for this duty of care.

5. Historical Significance and the Continuing Evolution of Insurance Law in Japan:

This 1912 decision was rendered under a very early version of Japan's Commercial Code. It's important to note that the specific statutory provision regarding the consequence of non-disclosure (Article 429 of the Commercial Code) was itself amended in 1911 (with effect from 1912, around the time this case would have been progressing). The pre-1911 version often led to the contract being deemed "void" for non-disclosure, while the 1911 amendment changed this to a right for the insurer to "rescind" the contract (a subtle but legally significant difference).

Legal commentary, such as the PDF provided with this case, often places this 1912 Daishin-in judgment in the context of other related Daishin-in decisions from that era (e.g., a 1907 case that also recognized the examining physician's authority to receive disclosures, and a slightly later 1916 case, which was the subject of the user's file h59.pdf, that further solidified the examining physician's role as an "organ of the company" with significant authority in the disclosure process). Together, these early cases helped to shape the foundational understanding of the roles and responsibilities of the various parties involved in the life insurance application and underwriting process in Japan.

While Japan's current comprehensive Insurance Act of 2008 has significantly modernized and codified many aspects of insurance law, including disclosure duties and the consequences of their breach, the fundamental principles explored in these early Daishin-in cases – such as the imputation of an agent's (like a physician's) knowledge or negligence to their principal (the insurer), and the establishment of appropriate professional standards of care – continue to be relevant concepts in legal analysis and provide valuable historical context for understanding the evolution of Japanese insurance jurisprudence.

Conclusion

The Daishin-in's 1912 decision in this life insurance case was a pioneering judgment in Japanese law. It addressed the critical role and responsibilities of an insurance company's examining physician within the context of an applicant's fundamental duty of disclosure.

The Court established that such an examining physician acts as an "organ" of the insurance company. Consequently, any negligence on the part of the physician during the pre-insurance medical examination – specifically, a failure to discover a pre-existing medical condition that an ordinary general practitioner, exercising a reasonable degree of care, would normally have detected – can be legally imputed to the insurance company.

If such imputed negligence leads to a situation where the insurer "could have known" about material facts that the applicant failed to disclose, then the insurer (under the legal framework applicable at that time) would lose its right to declare the policy void on the grounds of that non-disclosure.

The judgment set the standard of care for these insurer-appointed examining physicians as that of a competent, ordinary general practitioner, rather than that of a top-level specialist. This decision sought to strike a balance, upholding the importance of the insured's disclosure duty while also placing a clear responsibility on insurers to ensure that their own risk assessment processes, including medical examinations, are conducted with a reasonable and appropriate level of professional diligence. While specific statutory provisions have evolved considerably since 1912, this early Daishin-in ruling laid important groundwork for understanding the insurer's responsibilities in the underwriting process and the legal consequences of errors made by those acting on its behalf to assess the risk to human life.