The Definition of "Employee" in Japanese Labor Law: Insights from a Landmark Supreme Court Ruling

Judgment Date: November 28, 1996

Case Name: Claim for Revocation of Administrative Disposition Denying Medical Compensation Benefits, etc. (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench)

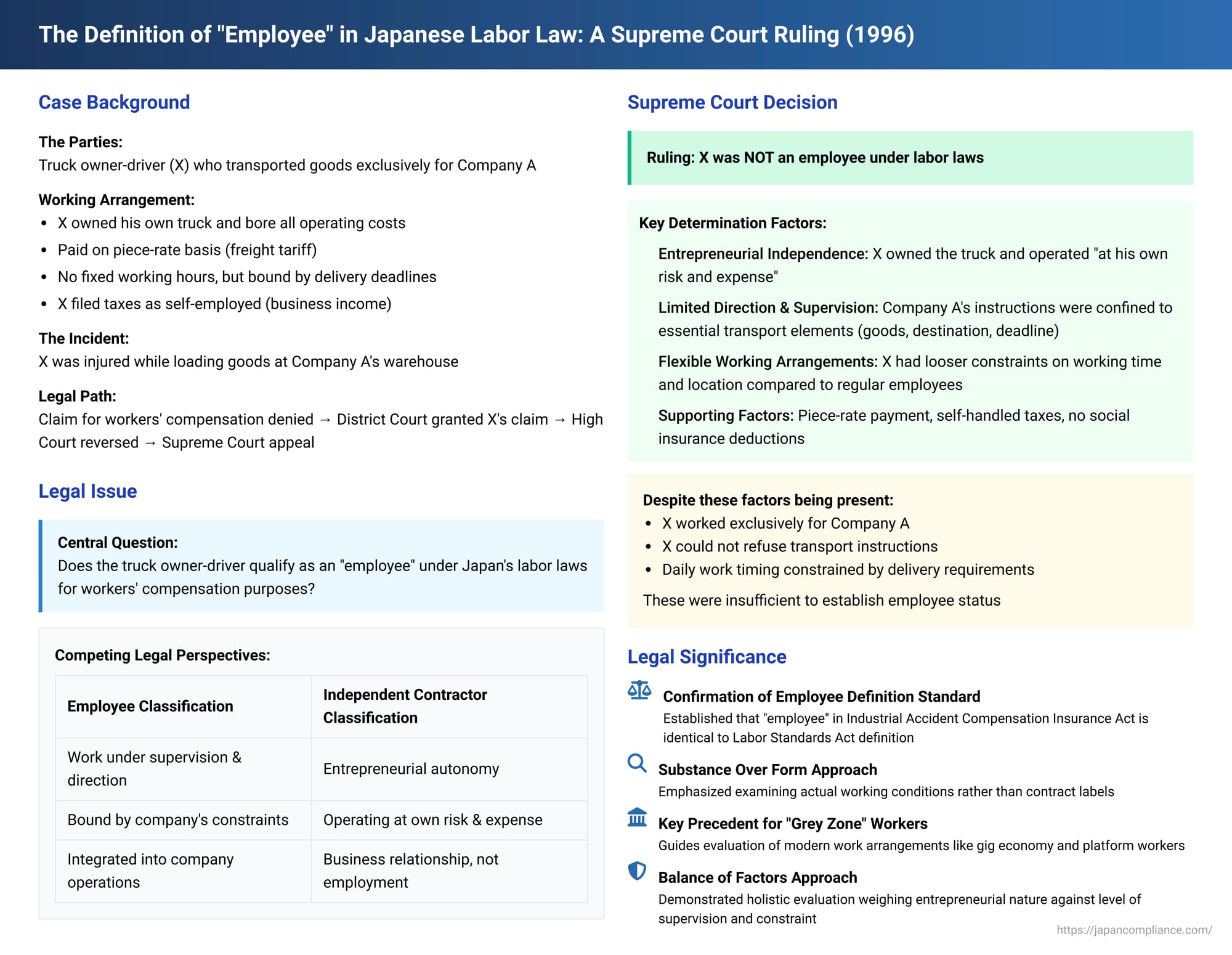

This blog post delves into a significant Japanese Supreme Court judgment issued on November 28, 1996. The case revolved around whether an individual truck driver, working under specific contractual and operational conditions, qualified as an "employee" under Japan's labor laws, particularly for the purposes of receiving benefits under the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act. The ruling provides crucial insights into the criteria used by Japanese courts to distinguish between employees and independent contractors.

Background of the Dispute

The case involved an individual, X, who owned his truck and transported products for Company A, a manufacturer and seller of goods such as cardboard. Company A, seeking to reduce costs and avoid liability for traffic accidents, had opted not to maintain its own transportation department. Instead, it outsourced these services. Initially, A contracted with corporate transport businesses. However, to exert more direct control over transport operations and respond to fluctuating demand, A began entering into exclusive contracts with individual owner-drivers like X.

X and Company A had an oral agreement for continuous transportation services. During these discussions, A’s representative informed X that owner-drivers were not considered employees of A. Furthermore, A stated it would not be responsible for traffic accidents occurring during transport, advising X to secure not only compulsory motor vehicle liability insurance but also voluntary automobile insurance. X was also told he would be liable for any damage to transported goods. X acknowledged these terms. Beyond this, there were no specific agreements regarding the contract's duration, working days, holidays, or the number of deliveries.

Key Facts Regarding X's Work Arrangement

The Supreme Court and lower courts meticulously examined the factual circumstances of X's engagement with Company A:

- Nature of Instructions: Company A's instructions to X were generally limited to the type of goods to be transported, the destination, and the delivery deadline. A did not dictate the driving route, departure times, or specific driving methods. Once a delivery was completed, X was not assigned other tasks until receiving instructions for the next transport job.

- Working Hours and Autonomy: Unlike Company A's regular employees, X did not have fixed starting and ending times. After completing the day's deliveries and receiving instructions for the next day's first delivery, X could load his truck and return home. He was permitted to proceed directly to the first delivery location the following day without first reporting to A's premises.

- Remuneration Structure: X was paid on a piece-rate basis. His earnings were determined by a freight tariff that considered the truck's load capacity and the transport distance.

- Assumption of Expenses: X bore all operational costs associated with his truck. This included the purchase price of the vehicle, fuel, maintenance and repair costs, and highway tolls incurred during deliveries.

- Taxation and Social Security: Company A did not withhold income tax from X's remuneration, nor did it deduct social insurance or employment insurance premiums. X filed his own annual income tax returns, declaring his earnings as business income.

The Injury and Subsequent Legal Proceedings

X sustained an injury when he slipped and fell while loading goods onto his truck at Company A's warehouse. He subsequently filed a claim with Y, the Director of the local Labor Standards Inspection Office, for medical compensation benefits and temporary disability compensation benefits under the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act.

Y denied X’s claim, reasoning that X did not meet the definition of an "employee" under the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act. In response, X initiated a lawsuit seeking the revocation of this administrative decision.

Lower Court Rulings:

- The Court of First Instance (Yokohama District Court): This court found in favor of X. It determined that the degree of temporal constraint X experienced was not significantly different from that of A's regular employees. Moreover, it found that the content of X's work was unilaterally determined by A's instructions. Based on these factors, the court concluded that X's work constituted the provision of labor under a relationship of subordination to Company A, thus qualifying him as an employee under the Act.

- The Court of Second Instance (Tokyo High Court): This court overturned the first instance decision, ruling against X. The High Court opined that in borderline cases where the determination of employee status is particularly challenging, the intentions of the contracting parties should be respected as much as possible, provided there are no illegalities or circumstances indicating that the arrangement does not reflect the true intentions of the worker. Applying this reasoning, the High Court concluded that X was not an employee under the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act. X subsequently appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, on November 28, 1996, dismissed X's appeal.

Equivalence of "Employee" Definition: The Court first affirmed the High Court's stance that the definition of an "employee" for the purposes of the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act is identical to the definition of an "employee" under the Labor Standards Act. This was a significant point, as it was the first time the Supreme Court explicitly endorsed this long-held interpretation by lower courts and legal scholars.

Reasoning for Denying Employee Status: The Supreme Court’s core reasoning for concluding that X was not an employee hinged on several factors derived from the established facts:

- Entrepreneurial Risk and Calculation: X owned the truck, a primary piece of operational equipment, and conducted the transport business "at his own risk and expense." This indicated a degree of entrepreneurial independence.

- Limited Scope of Direction and Supervision: Company A’s instructions were confined to elements naturally essential for accomplishing the transport task (i.e., specifying the goods, destination, and delivery time). The Court found that A did not exercise "specific direction and supervision" over the detailed execution of X's work.

- Looser Temporal and Spatial Constraints: The degree of constraint regarding X's working time and location was "far looser" compared to that of A's regular employees. X had considerable flexibility in managing his daily schedule outside the core delivery requirements.

- Overall Assessment of Subordination: Based on the above, the Court concluded that the evidence was insufficient to establish that X provided labor under Company A's substantial direction and supervision.

- Supporting Factors (Remuneration and Tax Treatment): The method of remuneration (piece-rate based on output) and the handling of public taxes and social contributions (X managing his own taxes and no deductions by A) further supported the conclusion that X was not an employee under the Labor Standards Act.

The Supreme Court also considered other facts that had been established by the High Court, such as:

- X worked exclusively for Company A.

- X did not have the freedom to refuse transport instructions from A's transport coordinator.

- X's daily start and end times were, in practice, dictated by the nature and timing of the instructions received from A's coordinator.

- The freight tariff paid to X was reportedly 15% lower than the standard rates published by a relevant trucking association.

Despite these elements, which might suggest some level of dependency or control, the Supreme Court maintained that they were not weighty enough to classify X as an employee under the Labor Standards Act, and consequently, he was not an employee for the purposes of the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act. The Supreme Court thus upheld the conclusion reached by the High Court, although, as will be discussed, its underlying reasoning on certain points differed.

Analysis and Broader Implications of the Judgment

This Supreme Court decision carries significant weight in Japanese labor law, offering clarity on the multifaceted assessment of "employee" status.

1. Scope of "Employee" Definition:

The explicit confirmation by the Supreme Court that the term "employee" in the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act aligns with its definition in the Labor Standards Act is foundational. This principle extends the relevance of the Court's reasoning in this case to a wide array of other Japanese labor statutes that adopt or refer to the Labor Standards Act's definition of an employee, such as the Minimum Wages Act and the Industrial Safety and Health Act. Furthermore, the Labor Contracts Act, enacted later, also contains a definition of "employee" that is fundamentally similar (though it omits the requirement that the counterparty be a "business"). Therefore, the criteria discussed in this judgment remain pivotal for determining the applicability of numerous individual labor relationship laws in Japan.

2. Core Criteria for Determining Employee Status:

The Labor Standards Act (Article 9) defines an "employee" as one who is "used" in a "business or office" and is "paid wages." Judicial precedent has consistently interpreted this to mean assessing:

* Whether the work is performed under the direction and supervision of the employer (指揮監督下の労働 - shiki kantoku-ka no rōdō).

* Whether the remuneration received is in exchange for labor (労務の対価としての報酬 - rōmu no taika toshite no hōshū).

This determination is made based on the actual conditions of work, irrespective of the formal title or classification of the contract (e.g., employment contract, independent contractor agreement, quasi-mandate contract).

Legal scholarship and prior court rulings, notably summarized in a 1985 report by the Labor Standards Act Study Group (a private advisory body to the then Minister of Labor), have identified several key factors for this assessment:

- Primary Factors:

- (a) Freedom to Accept or Refuse Work/Instructions: The extent to which the individual can choose whether to accept or decline specific work assignments or instructions.

- (b) Subjection to Direction and Supervision in Work Performance: The degree to which the employer controls how the work is performed, including specific methods and processes.

- (c) Constraints Regarding Work Location and Hours: Whether the individual is bound by fixed working times and locations set by the employer.

- (d) Substitutability of Labor: Whether the individual is permitted to have someone else perform their duties.

- (e) Nature of Remuneration as Consideration for Labor: How remuneration is calculated and paid, and whether it primarily reflects payment for labor provided rather than for achieving a specific outcome.

- Supplementary Factors (especially in borderline cases):

- (f) Entrepreneurial Nature (事業者性 - jigyōsha-sei): The extent to which the individual bears business risks, invests their own capital, and operates like an independent business entity.

- (g) Exclusivity of Service (専属性 - senzoku-sei): Whether the individual works exclusively or primarily for one principal.

- (h) Parties' Perceptions and Formalities: How the parties themselves view the relationship, as evidenced by contract terms, tax treatment, and social security contributions (though these are not solely determinative).

While the Supreme Court in this specific case did not lay out a comprehensive abstract test, its analysis, particularly its focus on whether X "provided labor under A's direction and supervision," aligns closely with these established factors.

3. The Supreme Court's Application of Criteria in This Case:

- Distinguishing Necessary Instructions from Substantive Supervision: The Court appeared to downplay the significance of instructions that are inherently necessary for the nature of the outsourced work. For instance, in a transport task, specifying the cargo, destination, and delivery time is essential for the job's completion, regardless of whether it's an employee or an independent contractor performing it. The Court implicitly distinguished these from the more pervasive and detailed control over the manner of work performance that typifies an employment relationship. De facto constraints arising from such necessary instructions were also not given overriding weight.

- The Interplay of Entrepreneurial Nature, Supervision, and Constraints: A key takeaway is the Court's emphasis on the "entrepreneurial nature" of X's work. Because X owned his truck and operated "at his own risk and expense" (a strong indicator of (f) entrepreneurial nature), and because the Court found the levels of (b) specific direction and supervision and (c) temporal/spatial constraints to be weak, it concluded that X could not be deemed to be providing labor under A's direction and supervision. The presence of other factors, such as (g) X's exclusive engagement with Company A, was insufficient to override this assessment. This suggests that where entrepreneurial characteristics are strong, a significant degree of direction, supervision, or binding constraint is necessary to establish employee status.

- Stance on the Role of "Party Intention": The High Court had suggested that in ambiguous, borderline cases, the expressed intentions of the parties should be a primary consideration. The Supreme Court, while upholding the High Court's conclusion, did not explicitly adopt this part of its reasoning. Legal commentators have noted that this subtle divergence is important. Relying heavily on party intention in determining the application of the Labor Standards Act can be problematic, especially given potential imbalances in information and bargaining power between individuals and companies. The Labor Standards Act contains mandatory protective provisions, and allowing their application to be easily dictated by the "intent" expressed in a contract, which may not reflect the true underlying relationship or the worker's genuine free will, could undermine the Act's purpose.

4. Further Nuances and Considerations Arising from the Judgment:

- Consistency with Flexible Employment Forms: The emphasis on strong direction/supervision or constraints for affirming employee status, especially when entrepreneurial elements exist, must be carefully balanced. Japanese labor law recognizes certain flexible employment arrangements for employees, such as the discretionary labor system (裁量労働制 - sairyo rōdō sei) for specialized or creative roles, and the highly skilled professional system (高度プロフェッショナル制度 - kōdo purofesshonaru seido). Employees under these systems can have relatively lenient direct supervision and fewer constraints on working hours while still being considered employees. Any framework for assessing employee status needs to be coherent with these existing categories.

- Substantive Evaluation of "Entrepreneurial Nature": The assessment of entrepreneurial nature should not be superficial. It's not merely about who formally bears certain costs (like X paying for his truck and fuel). A more substantive inquiry should examine whether the individual genuinely had the autonomy, discretion, and opportunity to increase their income through their own skill, judgment, and business acumen. This is crucial to prevent companies from easily circumventing labor law protections simply by shifting operational costs and risks onto individuals through contractual arrangements, as might have been Company A's motivation.

- Potential for Affirming Employee Status in Other Contexts: The judgment does not close the door on affirming employee status in situations where the entrepreneurial nature is less pronounced or where constraints are not as weak. If an individual's entrepreneurial character is not strong, and even if the constraints on work location and hours are not exceptionally rigid, the presence of a certain degree of direction and supervision, coupled with supplementary factors like exclusivity, could still potentially lead to a finding of employee status.

Legal Protection for Individuals Not Classified as Employees

When an individual is not recognized as an "employee," the protections afforded by the Labor Standards Act and many other individual labor relationship laws do not directly apply. However, this does not necessarily mean a complete absence of legal recourse or protection:

- Analogical Application of Civil Law Norms: Principles from civil law, including those underpinning the Labor Contracts Act, might be applied by analogy to provide some protection in disputes involving worker-like individuals, especially concerning contractual fairness or good faith. There is ongoing academic debate about whether such analogical application can extend to the more stringent, sometimes penal, provisions of the Labor Standards Act.

- Special Enrollment in Industrial Accident Insurance: Recognizing that some non-employees work in conditions similar to employees and face comparable risks, Japan has a "special enrollment system" (特別加入制度 - tokubetsu kanyū seido) within the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act. This system allows certain categories of non-employees (e.g., specific types of sole proprietors, including some transport owner-drivers) to voluntarily enroll and receive protections similar to those afforded to employees. The scope of this special enrollment system was expanded in 2021.

- Evolving Discussions on "Employment-Like" Work: In recent years, there has been a notable increase in individuals engaged in "employment-like working arrangements" (雇用類似の働き方 - koyō ruiji no hatarakikata). This trend is fueled by economic shifts towards service industries, the rise of the gig economy, advancements in information and communication technology, and increased outsourcing by companies. These workers often fall into a grey area, not clearly fitting the traditional definitions of either "employee" or "independent business operator." Consequently, there are active discussions and studies in Japan, including those by governmental bodies like the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, exploring how to ensure appropriate legal protections for this growing segment of the workforce.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in the case involving X and Company A remains a pivotal reference point for understanding the criteria for "employee" status under Japanese labor law. It underscores a holistic approach, weighing various factors related to the substance of the working relationship, with particular attention paid to the balance between the employing entity's direction and supervision and the individual's entrepreneurial autonomy and risk-bearing. The principles elucidated in this case continue to inform legal analyses as work styles evolve and the lines between traditional employment and independent work become increasingly nuanced.