The Definition of a "Criminal": Japan's Landmark Case on the Crime of Harboring

Imagine a friend appears at your door in a panic. They tell you they are wanted by the police for a serious crime, but they swear they are innocent. You, believing them or simply out of loyalty, decide to hide them in your home. By doing so, have you committed the crime of "Harboring a Criminal"? Does the legal definition of a "criminal" require the person to have been tried and convicted, or does it also include someone who is merely a suspect under investigation?

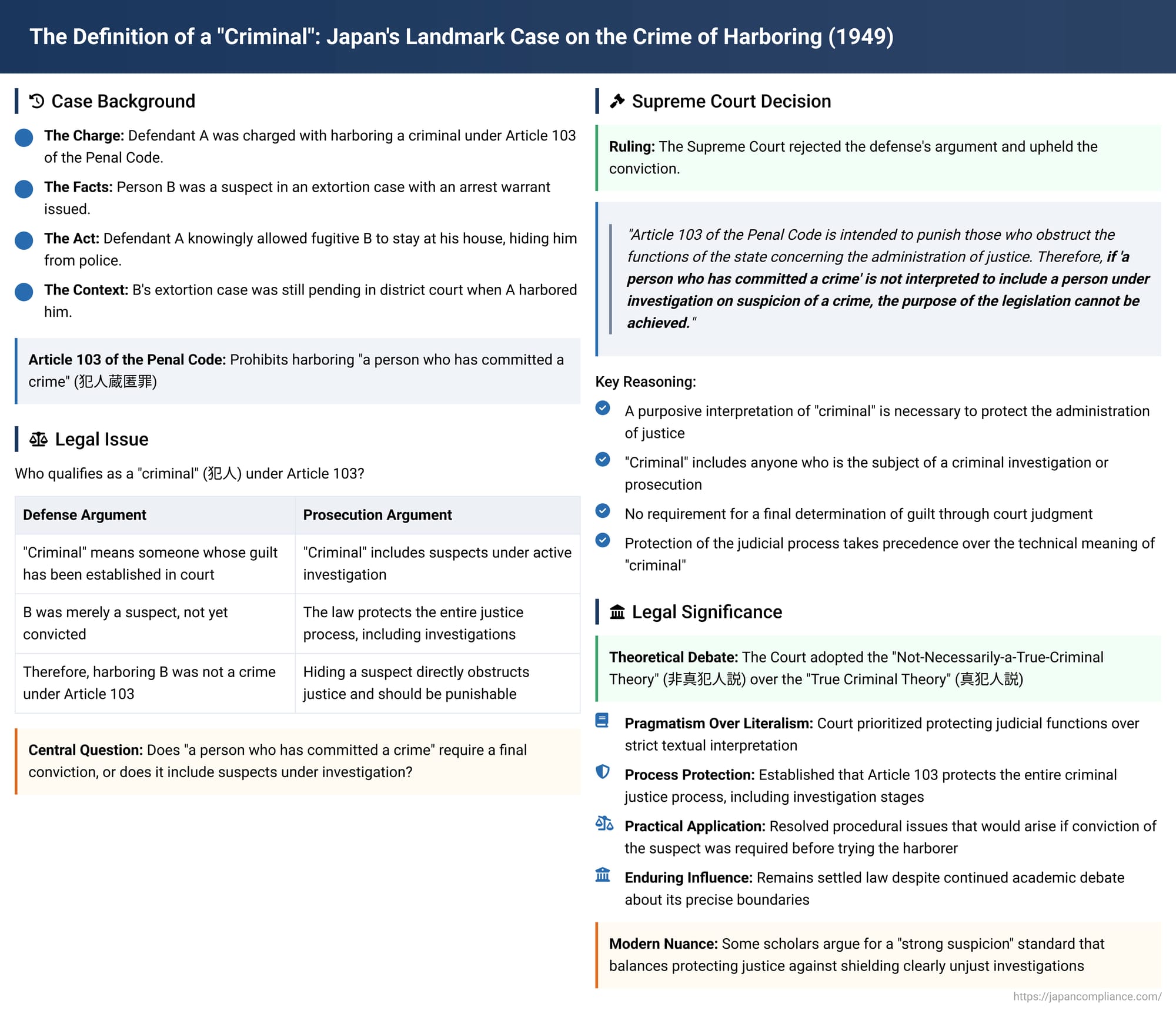

This fundamental question—about who qualifies as a "criminal" for the purposes of obstruction of justice—was the subject of a foundational decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on August 9, 1949. The ruling, issued in the early years of Japan's post-war legal system, provided a clear, pragmatic, and enduring answer that prioritized the protection of the state's judicial process.

The Facts: Hiding the Fugitive

The facts of the case were straightforward.

- A man, B, was a suspect in an extortion case. An arrest warrant had been issued for him, and he was on the run from the authorities.

- The defendant, A, knowing that B was a fugitive, allowed B to stay at his house for a period of time, thereby hiding him from the police.

The defendant was charged with the crime of Harboring a Criminal under Article 103 of the Penal Code. His defense was a direct challenge to the meaning of the statute. He argued that the law punishes the harboring of "a person who has committed a crime," and since B's extortion case was still pending in a district court, his guilt had not been definitively established. Therefore, the defense contended, B was not yet legally "a person who has committed a crime," and the charge of harboring could not stand.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Protecting the Process of Justice

The Supreme Court swiftly rejected this argument and upheld the conviction. The Court's reasoning was brief but powerful, focusing on the purpose of the law itself. It stated:

"Article 103 of the Penal Code is intended to punish those who obstruct the functions of the state concerning the administration of justice. Therefore, if 'a person who has committed a crime' is not interpreted to include a person under investigation on suspicion of a crime, the purpose of the legislation cannot be achieved."

This decision established that for the purpose of this crime, the term "criminal" is not limited to a person whose guilt has been proven by a final court judgment. It broadly includes anyone who is the subject of a criminal investigation or prosecution.

Analysis: A Fierce Theoretical Debate—"True Criminal" vs. "Suspect"

The Supreme Court's 1949 ruling placed it firmly on one side of a major and long-standing theoretical debate in Japanese criminal law concerning the definition of a "criminal" in this context.

- The "True Criminal" Theory (Shin-hannin setsu): This theory, which is the prevailing view in Japanese legal academia, argues that the statutory text "a person who has committed a crime" should be read literally. It contends that the person being harbored must be actually guilty of the underlying offense. The arguments for this view include its adherence to the plain language of the law and the idea that harboring a person who is ultimately proven innocent is a less blameworthy act.

- The "Not-Necessarily-a-True-Criminal" Theory (Hi-shin-hannin setsu): This theory, which the Supreme Court has consistently adopted, argues that the person being harbored need only be someone under suspicion or formal investigation. The arguments for this view are largely pragmatic and purposive:

- Protecting the Investigation: The primary purpose of the law is to protect the entire criminal justice process, including the crucial early stages of investigation and apprehension. Hiding a suspect directly obstructs this process, regardless of their ultimate guilt.

- Procedural Impracticality: Requiring a final conviction for the suspect before trying the harborer would be unworkable, leading to extreme delays. If the suspect successfully escapes forever, proving their guilt in the harborer's trial would become nearly impossible.

- Avoiding Inconsistent Verdicts: While not an insurmountable obstacle (a harborer's conviction could be overturned on retrial), having one court find a suspect guilty (in the harborer's trial) only for another court to find them innocent later creates legal chaos.

While the courts have consistently followed the "Not-Necessarily-a-True-Criminal" theory, there is a fascinating wrinkle in the case law. For cases where the harboring occurs before a formal police investigation has even begun, the Supreme Court appears to require proof that the person harbored was, in fact, a "true criminal." This suggests the Court's primary focus is on protecting the active process of justice once it is underway.

A More Nuanced Approach: Protecting Just Proceedings

The author of the commentary suggests a modified version of the Court's theory. While agreeing that the law protects the justice process, they argue that this protection should not be absolute. This view draws a parallel to the crime of Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty, where the public official's act must be "lawful" to be protected. Similarly, the state's criminal justice functions should only be protected when they are being exercised legitimately.

If it is obvious that the person being pursued is innocent and the state's suspicion is baseless, harboring that person should not be a crime. This leads to a refined standard where "a person who has committed a crime" is interpreted to mean a person under "strong suspicion" of having committed a crime, a standard similar to the probable cause required for a lawful arrest.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1949 decision remains a cornerstone of Japanese criminal justice law. It pragmatically defined "criminal" in the context of harboring offenses to include suspects under active investigation, prioritizing the protection of the state's ability to investigate and prosecute crime. This ruling ensures that individuals cannot undermine the entire justice process by hiding suspects and then arguing about their guilt or innocence later. While the decision is settled law, it continues to fuel a healthy academic debate about its precise boundaries, with modern scholars arguing that its protection should not extend to shielding a clearly unjust or baseless investigation. The case thus serves as a powerful illustration of the fundamental balance between protecting the state's power to pursue justice and ensuring that this power is exercised legitimately.