The Decisive Blow: Japan's Supreme Court on Causation When a Fatal Injury is Already Inflicted

Case Number: 1988 (A) No. 1124

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Date of Decision: November 20, 1990

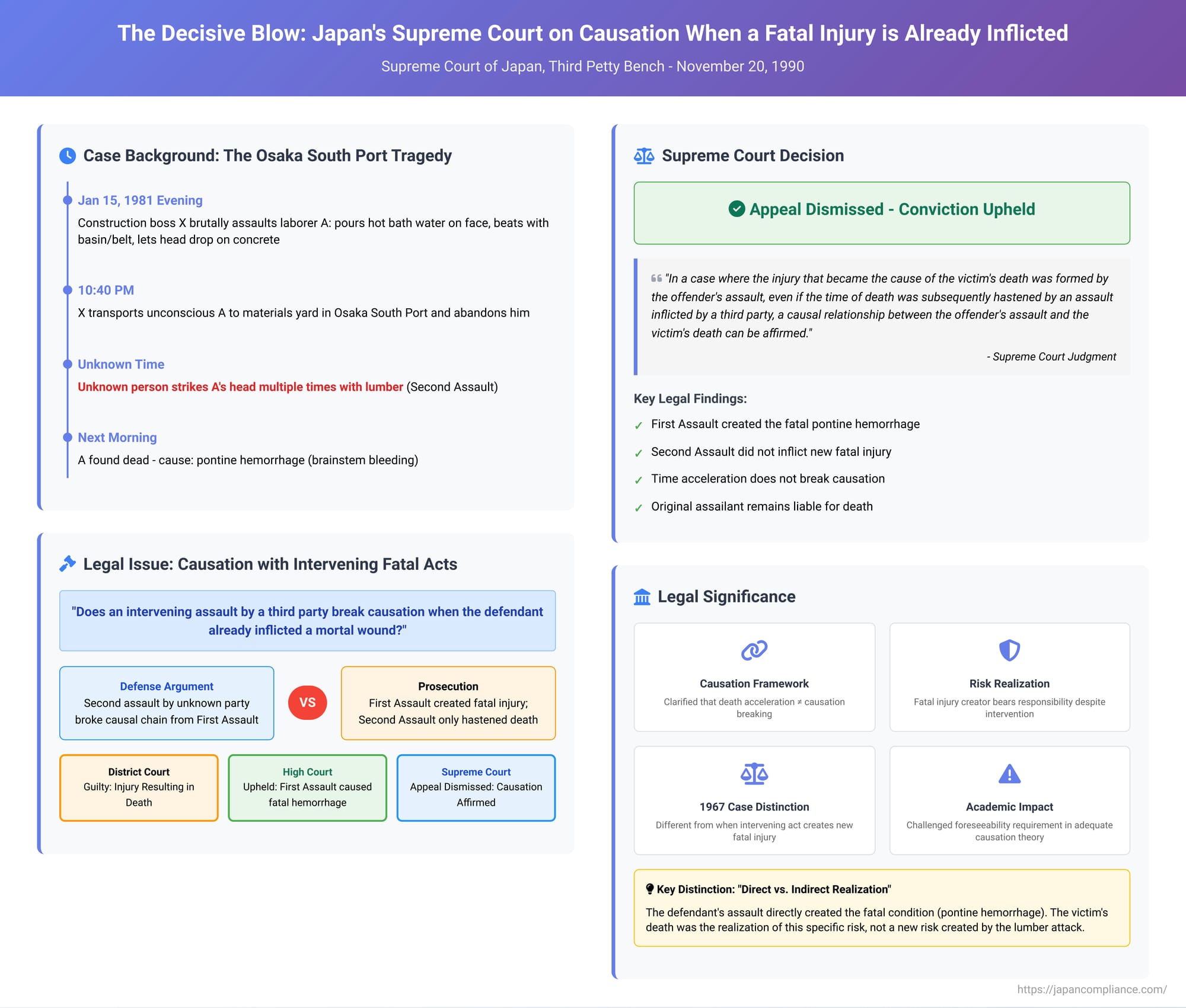

In the complex realm of criminal causation, courts are often faced with scenarios where multiple factors contribute to a victim's death. Following the landmark 1967 Supreme Court decision that dealt with a bizarre intervening act, Japanese law continued to evolve. The 1990 decision, often referred to as the "Osaka South Port Case," presents a different, yet equally compelling, factual matrix: What happens when a defendant inflicts a mortal wound upon a victim, and a second, separate assault by an unknown third party occurs before the victim succumbs? This case provides a crucial clarification on the law of intervening acts, distinguishing between an act that creates a new path to death and one that merely accelerates a death already in progress.

The Vicious Assault and the Mysterious Intervener: Facts of the Case

The defendant, X, was a construction business owner. On January 15, 1981, at his work camp in Mie Prefecture, he became enraged with the conduct of one of his laborers, A. What followed was a brutal and sustained assault (hereinafter the "First Assault"). X poured hot bath water on A's face, repeatedly beat him on the head with a plastic washbasin and a leather belt until he collapsed onto a concrete floor. While A was unconscious, X grabbed him by the hair, lifted his head, and let it drop back onto the concrete floor. He also doused the unconscious A with cold water from a pond.

Following this savage attack, X transported the still-unconscious A by car to a materials yard in the South Port (Nankō) district of Osaka. At approximately 10:40 PM, he abandoned A there and left the scene.

The victim, A, was later found dead in the early morning of the next day. The investigation, however, revealed another layer to the tragedy. While A was lying face down but still alive in the materials yard, an unknown person had struck him on the top of the head several times with a piece of lumber (hereinafter the "Second Assault").

The prosecutor initially argued that X had committed both assaults, but a confession by X regarding the Second Assault was later deemed inadmissible due to doubts about its voluntariness. The courts, therefore, proceeded on the factual basis that the Second Assault was committed by an unknown third party.

The medical evidence was paramount. The cause of A's death was determined to be an intracerebral hemorrhage, specifically a pontine hemorrhage (bleeding in the brainstem). The lower courts concluded that the First Assault by X had either directly caused this fatal hemorrhage or had critically exacerbated a minor, pre-existing hemorrhage to a fatal degree. The Second Assault by the unknown third party, by contrast, was found not to have caused the fatal brain injury itself. At most, it was determined to have worsened the existing bleeding and "hastened the time of death somewhat."

The Lower Courts' Findings: Pinpointing the Fatal Injury

The legal battle centered on which act, or actor, was legally responsible for the death.

The first instance court (Osaka District Court, decision dated June 19, 1985) found that the fatal hemorrhage was caused by the First Assault. It found insufficient evidence to conclude that the Second Assault had a significant impact on the already fatal bleeding. Finding reasonable doubt that X himself had committed the Second Assault, the court convicted X of injury resulting in death (shōgai chishi) based on his actions in the First Assault.

The appellate court (Osaka High Court, decision dated September 6, 1988) upheld this conviction. It sharpened the factual analysis, concluding that the First Assault by X had already created an injury sufficient to be the cause of death. The court found that the Second Assault by the third party did not inflict a new fatal injury but merely "had the effect of somewhat hastening the time of death" that was already underway due to the initial brain hemorrhage. Therefore, the High Court held that the First Assault had a direct causal relationship with the death, while the Second Assault did not, as it was not involved in creating the fatal condition itself.

The defendant's counsel appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the intervening Second Assault by a third party broke the chain of causation from his own actions.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal and upheld the conviction. In a concise and powerful statement, it laid down a clear legal principle that would guide future cases involving intervening acts. The Court held:

"In a case where the injury that became the cause of the victim's death was formed by the offender's assault, even if the time of death was subsequently hastened by an assault inflicted by a third party, a causal relationship between the offender's assault and the victim's death can be affirmed."

The Supreme Court found the High Court's judgment, which was based on this logic, to be legitimate. The ruling established a clear distinction: if an offender's act creates the mortal wound, that offender is legally responsible for the death, regardless of a subsequent, non-fatal intervention by another party that merely accelerates the dying process.

Legal Analysis: From "Foreseeability" to the "Realization of Risk"

This 1990 decision is best understood in dialogue with the 1967 "U.S. Serviceman" case and in the context of the evolution of Japanese causation theory.

1. A Critical Distinction from the 1967 "Serviceman Case"

The 1967 case established that a highly unforeseeable intervening act that independently causes the fatal injury can break the chain of causation. In that case, it was uncertain whether the defendant's initial impact or the passenger's subsequent, bizarre act of pulling the victim from the car roof caused the fatal head injury. Given the uncertainty, the court had to assume the latter, unforeseeable event was the cause, thus severing the causal link.

The 1990 Osaka South Port case presents the inverse scenario. Here, there was no such uncertainty about the origin of the fatal wound. The courts found as a matter of fact that the defendant's First Assault had already created the mortal injury (the pontine hemorrhage). The third party's Second Assault did not create a new, independent fatal injury. This factual distinction is the entire basis for the different legal outcomes.

- 1967 Case: Intervening act may have been the independent cause of the fatal injury -> Causation broken.

- 1990 Case: Defendant's act was the cause of the fatal injury; intervening act was not -> Causation affirmed.

2. The "Crisis" for Foreseeability and Adequate Causation

This ruling was seen by legal scholars as creating a "crisis" for the traditional "adequate causation theory," which heavily relied on the foreseeability of the causal chain. In this case, the Supreme Court affirmed causation without any discussion of whether the Second Assault by a third party was a "foreseeable" event.

This omission was significant. It suggested that when a defendant's contribution to the result is so overwhelming—i.e., when the defendant has already inflicted what amounts to a mortal wound—the foreseeability of subsequent, minor contributing events becomes irrelevant. The defendant has already set a fatal course in motion, and he cannot escape liability because someone else gives the victim a final, non-lethal push along that predetermined path.

3. The Modern Framework: "Realization of Risk" (Kiken no Genjitsuka)

The decision is best understood through the modern jurisprudential lens of "realization of risk." This theory analyzes causation by asking whether the harmful result is a concrete manifestation of the specific danger created by the defendant's act.

Under this framework, Japanese courts and scholars have developed several models for analyzing intervening act cases:

- Direct Realization: The defendant's act directly creates the fatal condition, and the subsequent death is a direct, albeit sometimes accelerated, materialization of that risk. The intervening act does not create a new, independent risk.

- Indirect Realization: The defendant's act creates a situation that then "induces" or leads to the intervening act, which in turn causes the result. For example, leaving a victim injured on a dark road, where it is foreseeable they might be hit by another car.

The 1990 Osaka South Port case is a textbook example of Direct Realization.

- The risk created by X's First Assault was the risk of death from a severe brain hemorrhage.

- The victim's death was the exact materialization of that risk.

- The Second Assault did not create a new fatal risk. It operated within the causal process already initiated and made fatal by the defendant. The death was still the "realization" of the danger from the pontine hemorrhage, not a danger from being hit with a piece of lumber.

This provides a coherent way to distinguish it from the 1967 case, where the passenger's act created a new and different risk (falling from a moving car) that was not a direct unfolding of the initial collision risk.

4. A Lingering Question: Causation and the Second Assailant

The case leaves a fascinating theoretical question unresolved. The lower courts ruled that the Second Assault, which "hastened the time of death," had no causal relationship to the death. From a purely "but-for" perspective, this is questionable: but for the second assault, the victim would have died later. The denial of causation suggests that to be legally relevant, a contribution to a result must be more significant than merely altering the timing of an already inevitable outcome. While the Supreme Court did not comment on this specific point, it remains a topic of academic debate in Japanese criminal law.

Conclusion

The 1990 Osaka South Port decision profoundly clarified the law of intervening causation in Japan. It established the vital principle that an offender who inflicts a mortal wound cannot escape liability for the resulting death simply because a third party later intervenes and accelerates the dying process.

By distinguishing this scenario from cases where an intervening act is the independent source of the fatal harm, the Supreme Court provided a more nuanced and practical framework for assigning criminal responsibility. The ruling solidifies a core tenet of causation: he who creates the decisive, fatal risk is responsible for its ultimate, tragic realization.