The Deceived Boss: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Forgery by 'Indirect Perpetration'

In any large organization, be it a corporation or a government agency, work flows through a hierarchy. A subordinate prepares a report, a manager reviews it, and a director signs off on it, lending their official authority to the document. This system relies on a foundation of trust. But what happens when that trust is broken? If a subordinate intentionally fills a report with false information, knowing their unsuspecting boss will sign it and turn it into an official document, who has committed the crime of "making a false document"? Can the subordinate, who lacks final signing authority, be held liable? Or does the law allow a guilty mind to escape punishment by hiding behind an innocent hand?

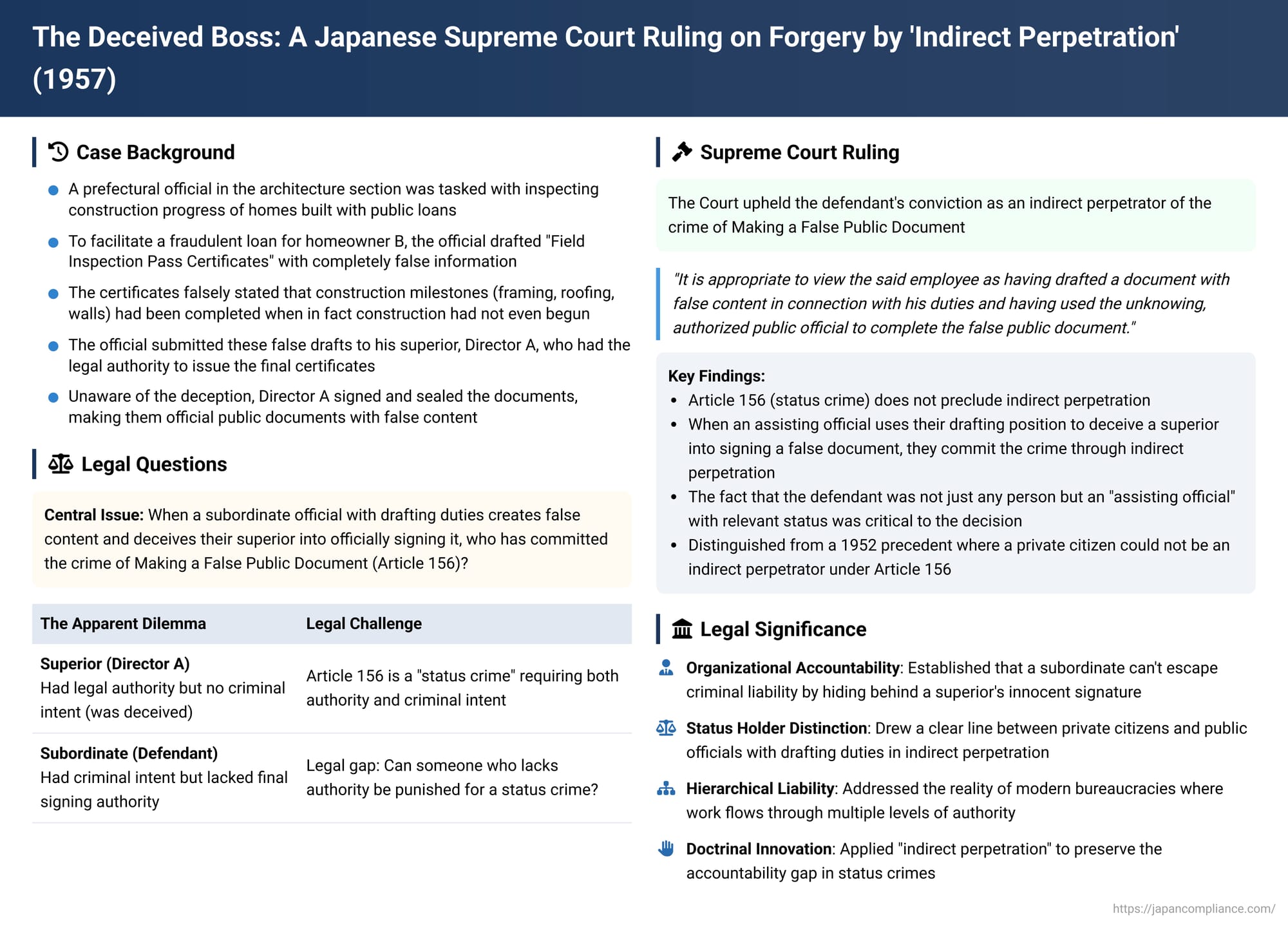

This fundamental question of accountability in a bureaucracy was addressed in a pivotal decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on October 4, 1957. The case, involving a deceptive public official and his unwitting superior, established how the legal doctrine of "indirect perpetration" applies to the crime of making a false public document, setting a precedent that remains vital for understanding organizational liability.

The Facts: The Phony Construction Report

The case centered on a public official working in the architecture section of a prefectural regional office in Miyagi Prefecture.

- The Defendant's Role: His official duties included reviewing building plans and inspecting the construction progress of homes being built with loans from the public Housing Loan Corporation. A key part of his job was to draft the official documents related to these inspections.

- The Scheme: To facilitate a fraudulent loan for a homeowner named B, the defendant drafted a series of "Field Inspection Pass Certificates." He filled these reports with completely false information, stating that key construction milestones—such as the erection of the house frame, roofing, and application of rough walls—had been completed. In reality, construction on the house had not even begun.

- The Act of Deception: The defendant then submitted these false draft documents to his superior, the regional office director, A. Director A was the official with the legal authority to create and issue the final certificates. Unaware of the true facts, the director was deceived into believing the reports were accurate and, based on this false information, affixed his name and official seal to the documents. This act transformed the defendant's false drafts into official, but fraudulent, public documents.

The Legal Puzzle: A Crime Without a Guilty Author?

This scenario created a legal puzzle.

- The Crime: The crime in question was Making a False Public Document (Article 156 of the Penal Code). This crime involves an official creating a document with false content. It is a "status crime" (mibun-han), meaning it can only be directly committed by a public official who possesses the specific authority to create the document in question.

- The Dilemma:

- The superior, Director A, had the legal authority to create the document, but he lacked the criminal intent, as he was an innocent party who had been deceived.

- The subordinate, the defendant, had the criminal intent, but he lacked the final authority to create the document himself.

- The Apparent Loophole: This appears to create a situation where a crime has clearly been committed, but neither individual seems to fit the traditional definition of the perpetrator. This is where the legal doctrine of indirect perpetration (kansetsu seihan) becomes crucial. This doctrine allows for a person who uses another, innocent individual as a "tool" to commit a crime to be held liable as the principal offender.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: The Assistant as Indirect Perpetrator

The Supreme Court upheld the defendant's conviction, explicitly affirming that he was guilty as an indirect perpetrator of Making a False Public Document. The Court reasoned:

- While Article 156 is a status crime requiring an authorized public official as the perpetrator, this does not preclude indirect perpetration.

- When an official who assists a superior and is in charge of drafting documents uses their position to create a false draft, and then submits it to their unsuspecting superior, causing the superior to mistakenly sign and seal it, this constitutes indirect perpetration of the crime.

- In such a case, the Court stated, "it is appropriate to view the said employee as having drafted a document with false content in connection with his duties and having used the unknowing, authorized public official to complete the false public document."

Analysis: Navigating a Maze of Law and Precedent

The Court's 1957 decision was significant because it had to navigate a complex and seemingly contradictory legal landscape.

- The Problem of Article 157: Another statute, Article 157, specifically punishes private citizens who, by making false declarations, cause an official to make a false entry in certain important documents (like passports or notarial deeds). This has led to the argument that the legislature intended for Article 157 to be the only available charge for this kind of indirect act, thereby precluding a general application of indirect perpetration to Article 156.

- Conflicting Supreme Court Precedents:

- In a 1952 decision, the Supreme Court had ruled that a private citizen who deceived an official could not be an indirect perpetrator under Article 156, and could only be charged under Article 157 if the specific document type matched. This seemed to close the door on the doctrine for this crime.

- The 1957 Court skillfully distinguished its case from the 1952 precedent. It explicitly noted that the prior case concerned a perpetrator who was "not a public official" and was therefore "not applicable to the present case."

- The "Assisting Official" as a Status Holder: The key to understanding the decision lies in recognizing the defendant's unique position. He was not a mere private citizen. He was a public official whose specific job duties included drafting the very documents in question. He held a relevant "status" as an "assisting official" (hojo kōmuin). Therefore, the case is not about a non-status holder committing a status crime—a scenario that most Japanese legal scholars argue is impossible. Rather, it is about one public official (the subordinate with drafting authority) using another (the superior with signing authority) as an innocent instrument.

Conclusion

The 1957 ruling on the deceived boss provides a vital and enduring framework for assigning criminal responsibility within hierarchical organizations. It established the crucial principle that a subordinate official who is the true intellectual author of a fraudulent document cannot escape liability by laundering their criminal intent through the innocent signature of a superior. The decision draws a clear line:

- A private citizen who deceives an official is generally not liable for Making a False Public Document under the general statute (Art. 156).

- An assisting public official, whose duties include drafting the document in question, is liable as an indirect perpetrator if they knowingly create a false document and deceive their superior into finalizing it.

This ensures accountability is placed where it belongs—with the individual who possessed the guilty mind and abused their official position to corrupt the integrity of public records.