The Critical Moment: Japanese Supreme Court on Securing Priority in Multi-Creditor Attachments and Third-Party Deposits

Date of Supreme Court Decision: March 30, 1993

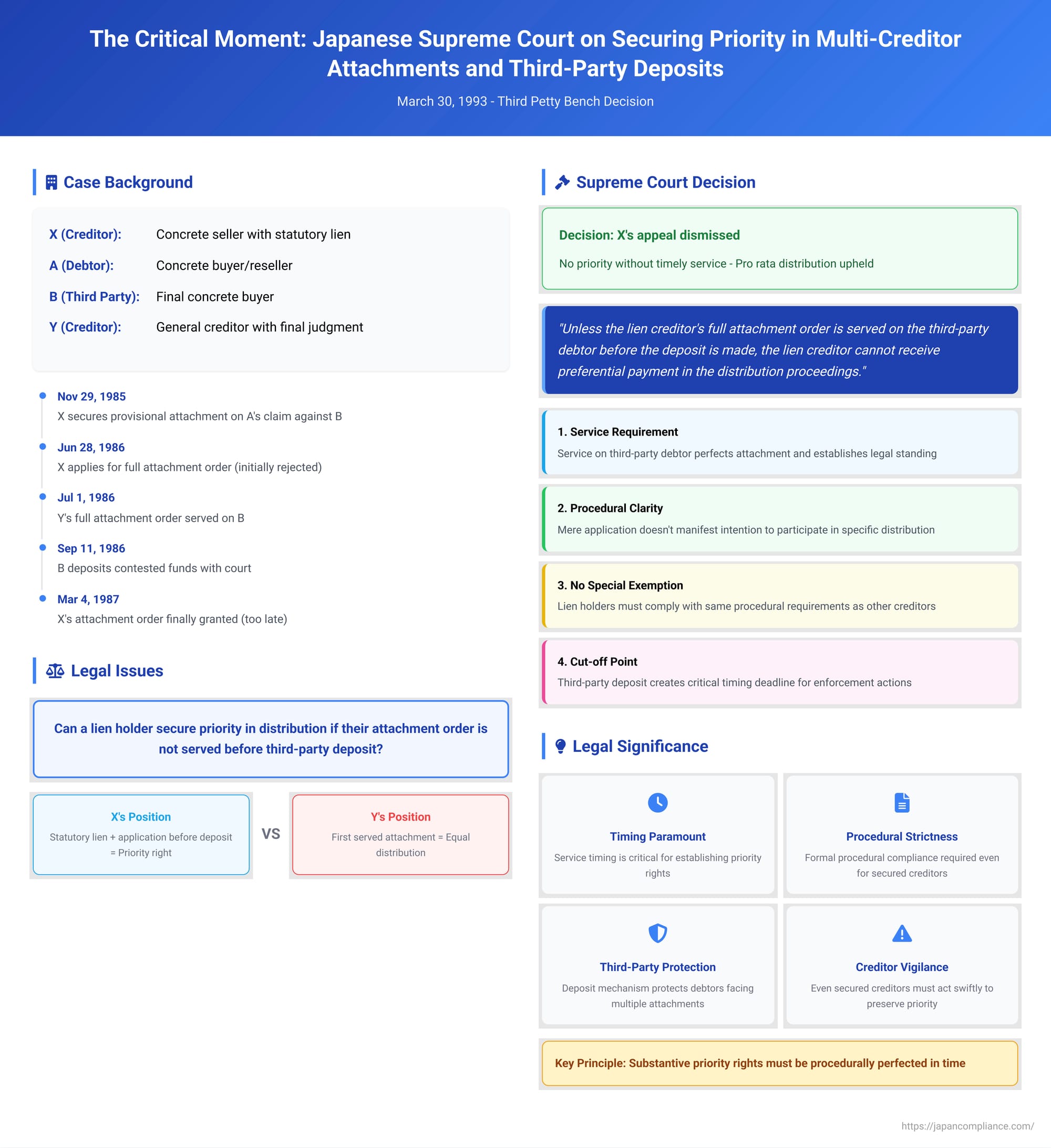

In the complex arena of debt recovery, particularly when multiple creditors pursue the same asset of a debtor, the timing and nature of legal actions can be paramount in determining who gets paid and in what order. A crucial decision by the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan, issued on March 30, 1993 (Showa 63 (O) No. 1453), addressed a highly specific but critical scenario: Can a creditor holding a statutory lien, who has taken preliminary steps to secure a claim and later applies for a full attachment order before a third-party debtor deposits the contested funds, assert priority in the distribution if their full attachment order is not formally served on that third-party debtor prior to the deposit? This ruling sheds light on the strict procedural requirements for establishing priority in Japanese civil execution proceedings.

The Factual Timeline: A Race Against Time and Competing Claims

The case involved a series of transactions and ensuing legal actions:

- The Underlying Transaction and Lien: X sold ready-mixed concrete to A. A, in turn, resold this concrete to B. For the unpaid price of the concrete it sold to A, X possessed a statutory seller's lien (動産売買の先取特権 - dōsan baibai no sakidori tokken) over the concrete and, by extension, a right of subrogation (物上代位権 - butsujō daiiken) against A's claim for the resale price from B.

- X's Initial Protective Step: On November 29, 1985, X secured a provisional attachment order (仮差押命令 - kari sashiosae meirei) against A’s claim for the resale price from B. This order was served on B, the third-party debtor, effectively freezing the claim to prevent A from collecting it or B from paying it to A.

- Y's Competing Action: Meanwhile, Y, another creditor of A holding a final judgment against A, took action. On June 30, 1986, Y obtained a full attachment order (債権差押命令 - saiken sashiosae meirei) against A's claim for the resale price from B. This order was served on B on July 1, 1986.

- X's Attempt at Full Enforcement: Prior to Y’s attachment order being served but after Y had initiated its action, on June 28, 1986, X applied to the execution court for its own full attachment order and an assignment order (差押・転付命令 - sashiosae/tempu meirei) against A's claim on B. This application was explicitly an exercise of X's subrogation rights under its statutory lien. However, X's application was initially rejected by the execution court.

- The Third-Party Debtor's Deposit: With X holding a provisional attachment and Y holding a full attachment against the same debt owed by B to A, B found itself in a bind. Consequently, on September 11, 1986, B deposited the amount of the resale price with the court, as permitted under Article 156, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Execution Act, and notified the court of the circumstances. This deposit effectively shifted the dispute from B to the distribution of the deposited funds among A's creditors.

- X's Full Attachment Order Finally Granted: Much later, on March 4, 1987, X's appeal against the initial rejection of its application for an attachment and assignment order was successful, and the appellate court granted the order. However, this was long after B had deposited the funds.

- The Distribution Dispute: The execution court, tasked with distributing the deposited funds, prepared a distribution statement (配当表 - haitōhyō) proposing to divide the money pro rata between X and Y based on their respective claim amounts, treating them as creditors of equal standing. X objected, insisting that its statutory lien and right of subrogation entitled it to priority. X then filed a lawsuit to challenge this pro rata distribution.

The Tokyo District Court (first instance) ruled in favor of X, recognizing its priority. However, the Tokyo High Court (second instance) reversed this decision, denying X's claim for priority. X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Adjudication: Service, Not Just Application, is Key for Priority in This Context

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of March 30, 1993, dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the Tokyo High Court's decision that denied X priority. The crux of the Supreme Court's reasoning was that the mere application for an attachment order, even if made by a lien holder exercising subrogation rights and even if filed before the third-party debtor deposits the funds, is insufficient to secure priority in a distribution triggered by another creditor's perfected attachment unless the lien holder's own attachment order is served on the third-party debtor before the deposit is made.

The Court's detailed reasoning was as follows:

- The Scenario Defined: The Court considered a situation where a statutory lien creditor (X) has made a provisional attachment on the target claim. Subsequently, another creditor (Y) effects a full attachment on the same claim, prompting the third-party debtor (B) to deposit the funds with the court under the Civil Execution Act. The lien creditor (X), before this deposit, applies for its own full attachment order as an exercise of subrogation. The question is whether X can claim priority in the distribution of the deposited funds if its full attachment order is not served on B before B makes the deposit.

- The Core Holding – No Priority Without Timely Service: The Supreme Court held that, under these circumstances, unless the lien creditor’s (X's) own full attachment order is served on the third-party debtor (B) before B deposits the funds, the lien creditor cannot receive preferential payment in the distribution proceedings arising from the other creditor's (Y's) attachment.

- Reasoning – Lack of Procedural Clarity for Participation:

- The Court emphasized that merely applying for an attachment order does not, in itself, make the applicant's intention to seek a share (let alone a prioritized share) in a specific, different attachment case (i.e., Y's attachment case) procedurally clear or manifest.

- To be entitled to participate in a distribution under Article 165 of the Civil Execution Act (which governs who can receive payment from the proceeds of an executed claim), a creditor must generally fall into one of two categories by the statutory deadline for demanding distribution (often linked to the third-party debtor's deposit or payment):

- Be an "attaching creditor" whose attachment order has been duly served on the third-party debtor and is effective with respect to the claim being executed.

- Be a "creditor who has demanded distribution" (配当要求をした債権者 - haitō yōkyū o shita saikensha) by formally filing such a demand with the execution court handling the case.

- A creditor who has only applied for their own attachment order, and whose order has not yet been served on the third-party debtor by the relevant cut-off time in the other creditor's proceedings, meets neither of these criteria.

- No Special Procedural Exemption for Lien Holders: The Supreme Court found no compelling reason to create a special rule or interpret the existing rules differently simply because the creditor who applied for the attachment order was doing so as an exercise of a statutory lien holder's right of subrogation. The substantive priority afforded by the lien does not excuse the creditor from complying with the procedural requirements for participating in a specific execution and distribution process initiated by another creditor.

Essentially, X’s failure to have its full attachment order (not just the earlier provisional one) served on B before B’s deposit meant that X had not procedurally perfected its claim for priority within the context of Y's successful attachment that led to the deposit.

Implications and Analysis of the Decision

This Supreme Court ruling carries significant weight in understanding the procedural intricacies of Japanese civil execution law, especially for secured creditors:

- The Paramountcy of Service: The decision underscores that the service of an attachment order on the third-party debtor is a critical procedural step. It is generally this service that perfects the attachment and formally establishes the creditor's legal standing concerning that specific claim against the third-party debtor, making it effective erga omnes (against all).

- "Application for Attachment" vs. "Demand for Distribution": A key point of contention, discussed in legal scholarship surrounding this case, was whether an application for one's own attachment order could be construed as implicitly including a "demand for distribution" in any competing attachment cases initiated by others. The argument, often phrased as "the greater includes the lesser," suggests that someone seeking to seize the entire claim for themselves (via their own attachment) inherently also seeks at least a share if a collective distribution occurs. The Supreme Court, however, sided with a stricter interpretation, aligning with a view that procedural acts must be explicit. An application to start one's own attachment proceeding doesn't automatically translate into a formal demand to join another's pre-existing proceeding for distribution purposes. The intention to participate in a specific, ongoing execution must be clearly and formally manifested.

- Rationale for the Stricter Procedural View: The commentary around this case highlights several reasons supporting the Court's stance, focusing on procedural stability and fairness:

- Procedural Certainty: Execution courts might not always be aware of all mere applications for attachment pending against the same debt, especially if filed at different times or if the third-party debtor has not yet made a complete declaration of the debt's status. If mere applications were sufficient to grant participation rights, it could create uncertainty and instability in distribution proceedings, as new claimants could emerge late in the process.

- Clarity for All Parties: Formal demands for distribution or perfected attachments provide clear notice to the court and other participating creditors. Relying on unperfected applications could leave other creditors unaware of all potential claims on the funds.

- Creditor's Choice and Risk: If a creditor, like X, chooses the path of obtaining its own full attachment order (perhaps aiming for an assignment order that would give it the entire claim directly, rather than just a share in a distribution), it accepts the procedural timeline and risks associated with that choice. If that order is not perfected in time (i.e., served before a critical event like a deposit triggered by another creditor's actions), the consequences follow.

- The Lien Holder's Procedural Burden: This case serves as a stark reminder that while a statutory lien provides substantive priority, the lien holder must diligently navigate the procedural landscape of civil execution to realize that priority. Delays in obtaining and serving their own attachment orders, even if due to initial court rejections that are later overturned, can be detrimental if another creditor successfully forces a deposit by the third-party debtor in the interim. X's earlier provisional attachment served to protect the asset from dissipation by A or premature payment by B, but it was not, in itself, sufficient to grant X priority in the distribution of funds arising from Y's subsequent perfected full attachment without X also perfecting its own full attachment or making a timely demand for distribution.

- The "Cut-Off" Point: The third-party debtor's deposit, made under lawful circumstances due to competing attachments, acts as a critical cut-off point. For a creditor to assert a claim against those deposited funds, their own enforcement actions (like a full attachment) must typically be effective (i.e., served on the third-party debtor) before this deposit crystallizes the fund for distribution.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's March 30, 1993, decision emphasizes the critical importance of adhering to formal procedural requirements in Japanese civil execution law, even for creditors who possess strong substantive priority rights like those derived from a statutory lien. The ruling makes it clear that for a lien holder to secure priority in a distribution of funds deposited by a third-party debtor due to a competing creditor's attachment, the lien holder's own full attachment order must be served on that third-party debtor before the deposit is made. A mere prior application for such an order, or even a prior provisional attachment, will not suffice to jump the queue if another creditor perfects their claim and triggers the deposit first. This decision underscores the need for vigilance and prompt, procedurally correct action by all creditors, including secured ones, in the often-complex race to recover debts.