The Criminal Cost of a Threat: A Japanese Ruling on Extortion and the 'Implied' Deal

Imagine a patron at a bar who, upon being presented with the bill, refuses to pay. Instead of sneaking out, they become aggressive, making threats and intimidating the staff. The frightened employees back down, abandoning their immediate demand for payment, and the patron walks out without paying. Have they committed the crime of extortion? They didn't physically take any money, and the staff never explicitly forgave the debt. So where is the crime?

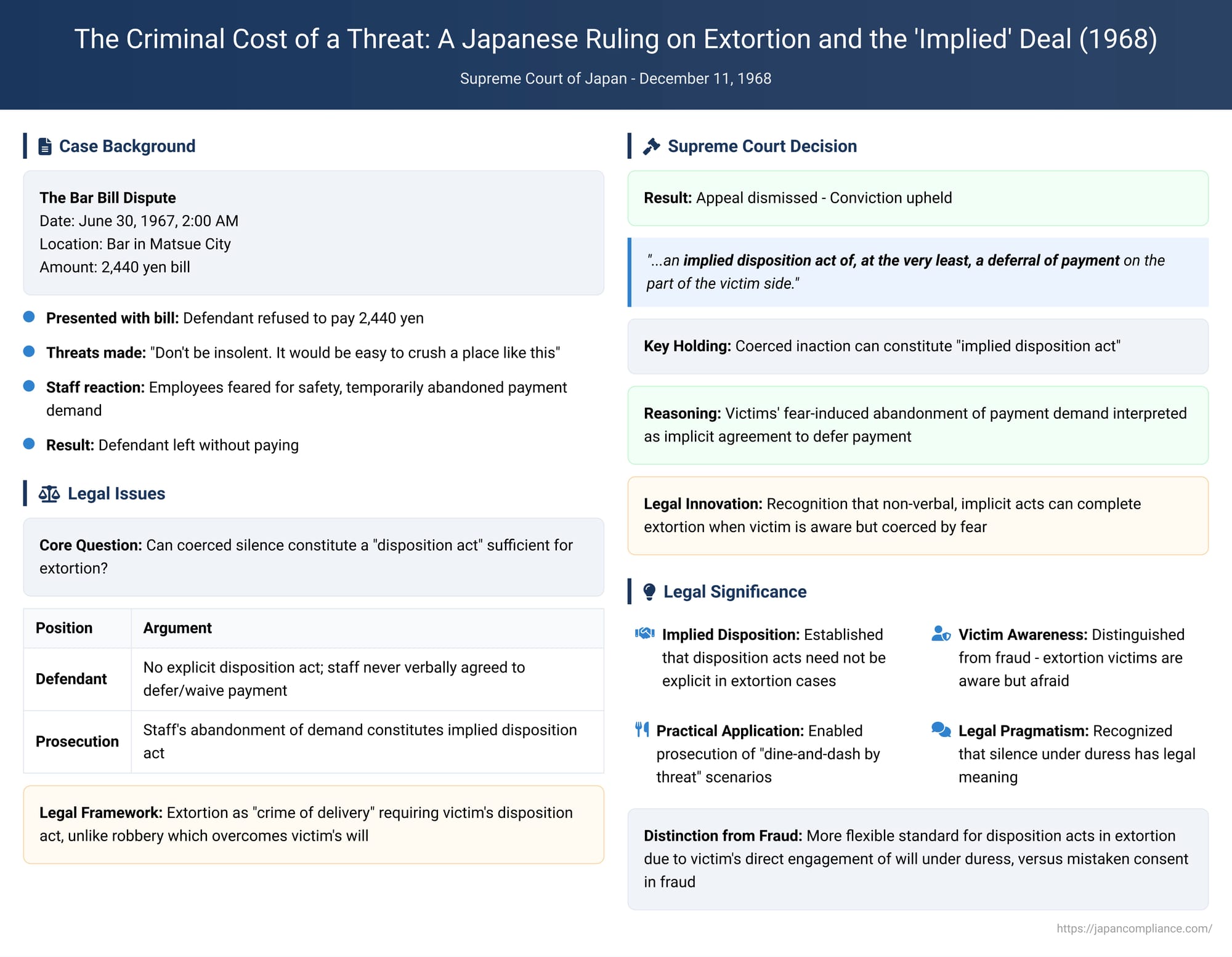

This question, which explores the anatomy of extortion, was the subject of a foundational decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on December 11, 1968. The Court's ruling established that a victim's coerced silence can be interpreted as an "implied disposition act," sufficient to complete the crime. The decision provides a crucial framework for understanding how threats can be used to illegally obtain a "pecuniary gain," such as the temporary evasion of a debt.

The Legal Framework: The Anatomy of Extortion

The crime of extortion, under Article 249 of the Japanese Penal Code, involves using threats or violence to coerce a person into delivering property or providing a pecuniary gain. Like fraud, it is considered a "crime of delivery" (kōfu-zai). This means it is distinct from robbery, where property is taken by force that overwhelms the victim's will. In extortion and fraud, the victim is coerced or deceived into making a "disposition act" (shobun kōi)—a conscious (though flawed) decision to transfer the property or benefit.

The requirement of a "disposition act" is a key, if unwritten, element of the crime. The central legal puzzle in this case was whether the staff's coerced inaction—their "temporary abandonment" of the demand for payment—could legally qualify as such an act.

The Facts: The Bar Bill and the Bully

On June 30, 1967, at around 2:00 AM, the defendant, after drinking at a bar in Matsue City, was presented with a bill for 2,440 yen. He refused to pay and became confrontational with the employees.

He made a series of threats, saying things like, "Are you trying to dirty my face with a demand like that? You talk too much. Don't be insolent. It would be easy to crush a place like this". This intimidating behavior caused the employees to fear for their safety and, as a result, they "temporarily abandoned their demand" for the payment.

The defendant was charged with and convicted of 2nd-paragraph extortion—extortion for a pecuniary gain (the gain being the evasion of the 2,440 yen debt). He appealed, arguing that since the employees never performed a concrete disposition act, such as verbally agreeing to defer or waive the payment, a key element of the crime was missing. He cited a 1955 Supreme Court decision on fraud , which had set a very high bar for what constitutes a disposition act in cases of debt evasion.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: An "Implied" Deferral of Payment

The Supreme Court rejected the defendant's appeal and upheld the conviction. In a concise but powerful parenthetical statement, the Court affirmed the High Court's reasoning, creating a landmark precedent.

The Court held that because the defendant "directed the threatening words... at the victims and intimidated them, thereby causing the victim side to abandon their demand," it was appropriate to recognize the existence of:

"...an implied disposition act of, at the very least, a deferral of payment on the part of the victim side."

This was a groundbreaking interpretation. The Court ruled that the victims' coerced inaction was not legally meaningless. Instead, it could be interpreted as an implicit, non-verbal action: an agreement to defer the payment to a later time. This "implied disposition act" was sufficient to complete the crime of extortion.

Analysis: Why is the Standard for Extortion Different from Fraud?

The Court's decision seems, at first glance, to conflict with its own stricter stance in fraud cases, like the 1955 "fake apple shipment" case (khk57). In that case, the Court found that merely tricking a creditor into "returning home with peace of mind" was not a sufficient disposition act. Why is the standard for extortion seemingly more relaxed?

The answer lies in the fundamental difference between the two crimes, particularly the victim's state of mind.

- In fraud, the victim is mistaken. They may not be fully aware of the nature or value of the right they are giving up. Because their consent is based on a misunderstanding, the law requires a clearer, more concrete disposition act to ensure the crime is not defined too broadly and to distinguish it clearly from theft.

- In extortion, the victim is afraid. They are not mistaken; they are fully aware that they are surrendering property or a right because they have been intimidated. Since their will is directly engaged—albeit under duress—the law can be more flexible in identifying the disposition act. A coerced agreement, even an unspoken one, is still a form of disposition.

The commentary on this case notes that in the real world, victims of extortion often find themselves in a situation where they are "aware that property or a pecuniary benefit is being transferred, but are forced to acquiesce due to fear". The Supreme Court's recognition of an "implied disposition act" is a pragmatic acknowledgment of this reality.

Conclusion: The Power of an Implied Act

The 1968 Supreme Court decision provided a practical and enduring solution to the problem of prosecuting "dine-and-dash by threat" and similar crimes. It established that, in the context of extortion, a victim's disposition act need not be a formal, explicit statement.

The ruling's core principle is that when a perpetrator uses threats to cause a creditor to abandon an immediate and legitimate demand for payment, that coerced inaction can be legally interpreted as an "implied disposition act"—specifically, an agreement to defer payment. This decision ensures that the law looks beyond formal declarations to the substantive reality of a situation, recognizing that a demand abandoned out of fear is a pecuniary benefit criminally gained by the perpetrator. It affirms that even silence, when compelled by a threat, can have a profound legal meaning.