The Corporate Savior or the Self-Serving Executive? A Japanese Ruling on Embezzlement in a Takeover Battle

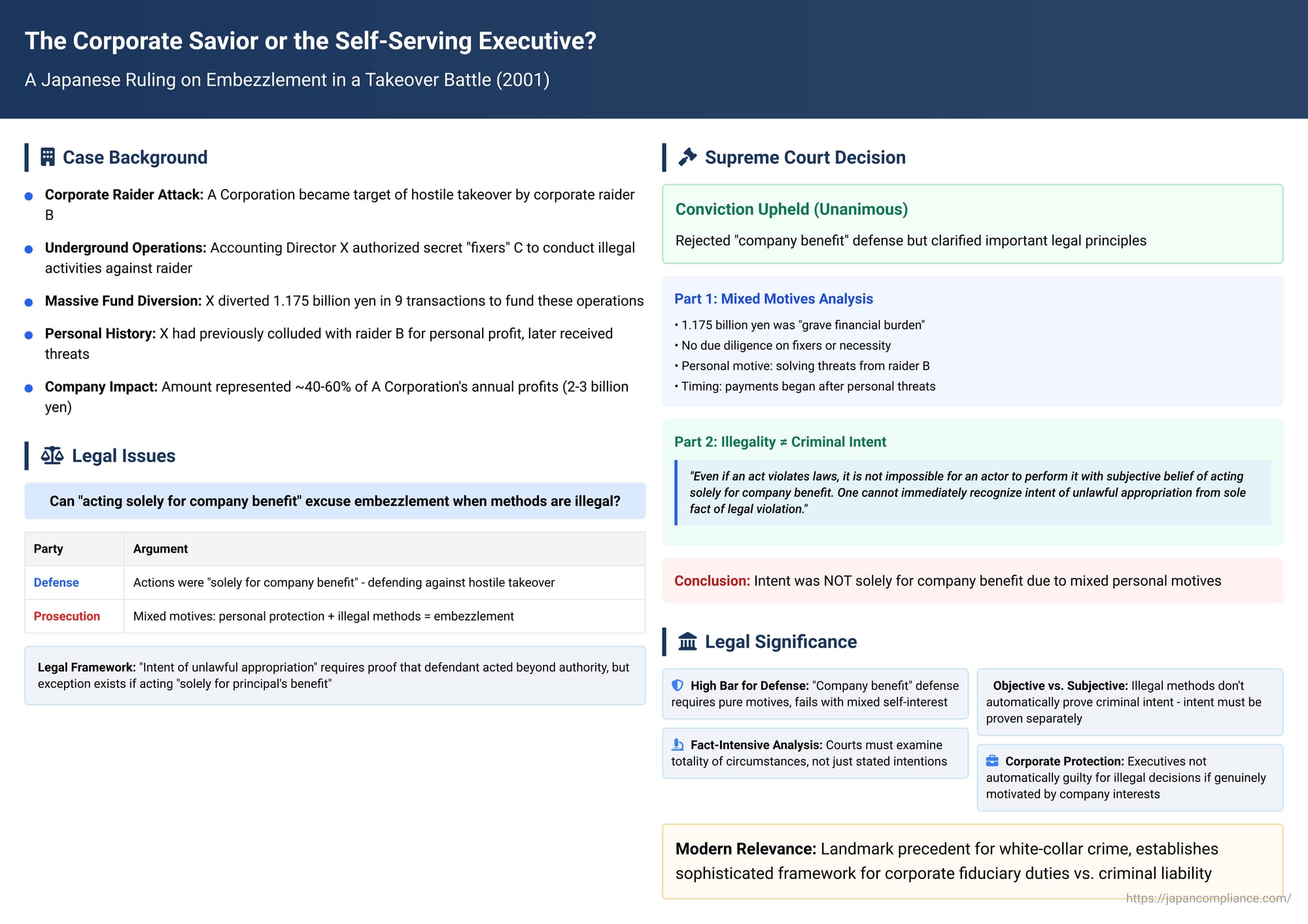

Imagine a company is under attack from a hostile takeover. A senior executive, believing they are acting to save the company, authorizes the use of corporate funds for a series of legally questionable "black ops" to thwart the takeover artist. When later charged with embezzlement, the executive argues that they were not acting for personal gain, but "solely for the benefit of the company." Is this a valid defense, especially if the methods used were themselves illegal?

This high-stakes corporate drama was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on November 5, 2001. The case, involving one of Japan's most famous corporate raids, forced the Court to provide a sophisticated and nuanced analysis of the crime of embezzlement. It clarified the limits of the "for the company's benefit" defense and established a crucial distinction between the objective illegality of an act and the subjective intent of the actor.

The Legal Doctrine: The "Intent of Unlawful Appropriation" and its Exception

The crime of embezzlement in Japan requires more than a simple misuse of entrusted property. In addition to the act itself, the law requires a specific state of mind known as the "intent of unlawful appropriation" (fuhō ryōtoku no ishi). In a foundational 1949 decision, the Supreme Court defined this as "the intent of a person who possesses the property of another to, in breach of the duties of their entrustment, dispose of that property as if they were the owner, despite having no authority to do so ".

Over the years, however, the courts have carved out a narrow exception to this rule. If a trustee, such as a corporate executive, can prove that they disposed of the property "solely for the benefit of the principal" (i.e., the company), they are deemed to lack the criminal intent of unlawful appropriation, and the charge of embezzlement fails. This case tested the limits of that very defense.

The Facts: A Corporate War and a Secret Slush Fund

The case centered on A Corporation and its accounting director, defendant X. A Corporation became the target of a hostile takeover attempt by a well-known corporate raider, B. In response, X and his subordinate, Y, decided to fight back using covert means. They conspired to hire "fixers," C, to conduct "underground operations" against the raider. These operations allegedly included pressuring B's financial backers to cut off his funding and distributing defamatory documents to damage his credit.

To fund these illicit activities, X and Y diverted massive sums of money from company A's accounts. In a series of nine transactions, they gave a total of 1.175 billion yen in cash to the fixers.

Complicating matters was X's own personal history. Before the takeover battle escalated, X had secretly colluded with the raider B in a previous scheme, personally profiting from the relationship. When X later sided with his company, B began threatening him, calling him a traitor. The first payment from company A's funds to the fixers occurred immediately after X received the first of these threats from B.

The Journey Through the Courts: From Acquittal to Conviction

The defendants' journey through the legal system was a roller-coaster, highlighting the complexity of the issue.

- The District Court (Acquittal): The trial court acquitted the defendants of embezzlement. It found that their actions, while problematic, were motivated by a desire to defend the company from a hostile takeover and were therefore undertaken "solely for the benefit of the principal".

- The High Court (Conviction): The appellate court overturned the acquittal and convicted the defendants. It provided two main reasons:

- Mixed Motives: X's intent was not solely for the company's benefit. He also had a powerful personal motive: to use the company's money to hire fixers who would neutralize the threats B was making against him personally.

- Illegality of the Act: The High Court also argued that the acts themselves—funding illegal activities like defamation and extortion, and planning a stock buyback that violated the Commercial Code—were things the company itself could not legally do. Therefore, an employee performing such acts could not, by definition, be acting for the company's benefit.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: A Two-Part Masterclass in Intent

The Supreme Court upheld the embezzlement conviction, but in a nuanced ruling, it embraced one of the High Court's arguments while explicitly rejecting the other.

Part 1: Rejecting the "Solely for the Company" Defense

The Supreme Court agreed with the High Court's "mixed motives" analysis. It conducted a holistic review of the facts and found that X's claim to have acted solely for the company's benefit was not credible. The Court considered several factors:

- The Immense Financial Burden: The 1.175 billion yen payout was a "grave financial burden" for A Corporation, whose annual profits were only around 2 to 3 billion yen.

- The Lack of Due Diligence: Despite the enormous sums and the highly risky nature of the "underground operations," there was no evidence that X had properly investigated the fixers or confirmed that the funds were necessary and being used effectively. He also failed to report the details of these massive expenditures to the company president.

- The Personal Motive: The Court gave significant weight to X's personal history with the raider B and the fact that the payments began immediately after B started threatening him. This indicated that X's intent was, at least in part, to use company funds to solve his personal problems and conceal his own past misconduct.

Considering these factors together, the Court concluded that the defendants' intent "was not solely for the benefit of A Corporation" and therefore, they possessed the necessary intent of unlawful appropriation.

Part 2: Rejecting the "Illegality Equals Guilt" Argument

In the most legally significant part of its decision, the Supreme Court disagreed with and rejected the High Court's second line of reasoning. The High Court had argued that because the executive's actions were illegal, they could not, by definition, be for the company's benefit. The Supreme Court declared this to be an error in legal interpretation.

The Court laid down a landmark principle separating the objective nature of an act from the subjective intent of the actor:

"The objective nature of the act and the subjective state of mind of the actor are, in principle, separate matters. Even if an act violates the Commercial Code or other laws, it is not impossible for an actor to perform it with the subjective belief that they are acting solely for the benefit of the company. Therefore, one cannot immediately recognize the actor's intent of unlawful appropriation from the sole fact that the act violates the Commercial Code or other laws."

The illegality of an act can be strong circumstantial evidence that the actor's motives might not be pure, but it is not, on its own, conclusive proof of the intent required for embezzlement.

Conclusion: A Nuanced Approach to Corporate Crime

The 2001 Supreme Court decision in this famous corporate case provides a sophisticated, fact-intensive framework for assessing embezzlement by corporate fiduciaries. It affirms that the "solely for the benefit of the company" defense, while a valid legal principle, is a high bar to clear and will fail if prosecutors can demonstrate that the executive had significant, self-serving motives.

At the same time, the ruling offers a crucial protection for corporate decision-makers by clarifying that the mere illegality of an action does not automatically make it a criminal embezzlement. The Court rightly separated the objective wrongfulness of an act from the subjective intent of the actor, ensuring that the focus in an embezzlement trial remains on proving that the defendant intended to usurp the rights of an owner, not just that they broke other laws. This decision remains a vital lesson in corporate governance and a cornerstone of Japanese white-collar criminal law.