The "Competitor" Defense: When Can Companies Deny Shareholders Access to Books? A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Judgment Date: January 15, 2009

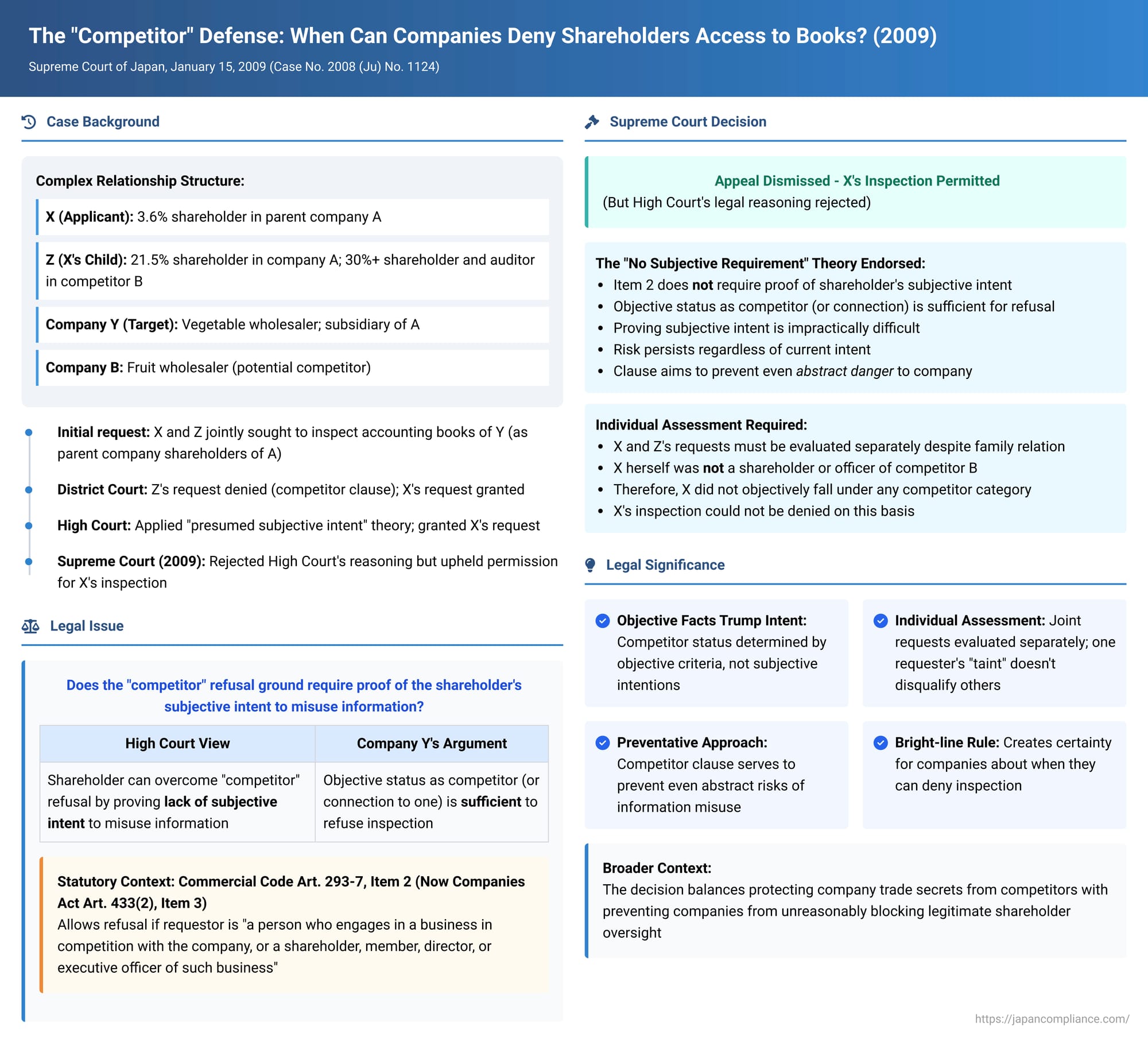

Shareholder access to corporate accounting records is a fundamental right, essential for ensuring transparency and enabling shareholders to protect their interests. However, this right is not absolute. Japanese corporate law provides specific grounds upon which a company can refuse such inspection requests. One of the most debated grounds involves shareholders who are, or are connected with, a competitor of the company. A key Supreme Court of Japan decision, dated January 15, 2009, provided crucial clarification on how this "competitor" clause should be interpreted, particularly regarding the relevance of the shareholder's subjective intent.

Facts of the Case: A Family Affair in the Wholesale Market

The case involved a company, Y, which operated a fruit and vegetable wholesale business primarily dealing in vegetables within the Nagoya City Central Wholesale Market (Northern Market). All of Y's issued shares were held by its parent company, A, which was also engaged in the fruit and vegetable brokerage business, similarly focusing on vegetables in the same market. Neither Y nor A had plans to handle fruits in the foreseeable future.

The applicant, X, was a shareholder in the parent company A, holding approximately 3.6% of its total voting rights. X's child, Z, held a more substantial stake in A, accounting for about 21.5% of the voting rights. Z also had a significant connection to another company, B. Z held over 30% of B's shares and served as its auditor. Company B was also a fruit and vegetable wholesaler, but it operated in the Nagoya City Central Wholesale Market (Main Market) and dealt exclusively in fruits, with no current or future plans to handle vegetables. Importantly, X, the applicant, held no shares in B and was not an officer of B.

X and Z, as shareholders of the parent company A, initially jointly applied to the court for permission to inspect and copy the accounting books of A's subsidiary, Y. This request was made under the provisions of the then-applicable Commercial Code (Article 293-8, Paragraph 1, which corresponds to Article 433, Paragraph 3 of the current Companies Act) allowing parent company shareholders to inspect subsidiary records under certain conditions, including obtaining court permission.

The court of first instance handled X's and Z's requests separately. Z's application was dismissed, with the court finding that a ground for refusal existed under the former Commercial Code Article 293-7, Item 2 (the "competitor clause," now Companies Act Article 433, Paragraph 2, Item 3). This decision concerning Z became final. However, the court found no such grounds for refusal concerning X and granted X permission to inspect Y's books within a certain scope.

Company Y appealed this decision to permit X's inspection. The High Court (the lower appellate court) took a different approach. It reasoned:

- Given that X and Z were mother and child, had initiated the proceedings together using the same legal representation, their requests were deemed substantially unified. Therefore, if a ground for refusal existed for Z, it should also apply to X.

- The High Court then interpreted the competitor clause. It opined that if the objective fact of the requesting shareholder being a shareholder of a competing company (as listed in the statute) is established, this generally constitutes a ground for refusal. However, it held that if the shareholder could prove they had no subjective intent to use the information obtained from the inspection for their own competitive activities or to allow other competitors to use it, then the refusal ground would not apply, and inspection could be permitted.

Applying this "presumed subjective intent" theory, the High Court found that A (and its subsidiary Y) and B were not in a competitive relationship concerning their current or near-future product lines (vegetables for A/Y, fruits for B). Consequently, Z could not possibly use Y's trade secrets about vegetables for B's fruit business. This, the High Court concluded, demonstrated Z's lack of subjective malicious intent. Based on this, it ruled that no refusal ground applied to Z, and therefore, none applied to X either. It partially upheld the permission for X to inspect.

Company Y further appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court, seeking permission to appeal.

The Supreme Court's Decisive Interpretation

The Supreme Court, in its decision dated January 15, 2009, ultimately dismissed Y's appeal, meaning the High Court's conclusion to permit X's inspection stood. However, the Supreme Court arrived at this conclusion through a starkly different legal reasoning, particularly concerning the interpretation of the competitor refusal clause.

The Court squarely addressed the question: For the competitor clause (then Commercial Code Art. 293-7 Item 2) to apply, is it necessary for the company to prove the shareholder has a subjective intent to misuse the information, or for the shareholder to prove the absence of such intent?

The Supreme Court held that the High Court's reasoning was incorrect. It stated:

- No Subjective Intent Required for Refusal: The competitor clause (Item 2) is distinct from other refusal clauses (like Item 1 of the same Article, which explicitly mentions subjective elements like "for the purpose of harming the company's business operations or the common interests of the shareholders"). Item 2, by its wording, does not require the existence of a subjective intent on the part of the shareholder to use the information for their competitive business.

- Rationale for Excluding Subjective Intent: The Supreme Court provided several reasons for this interpretation:

- Proving subjective intent is generally difficult.

- Even if a shareholder lacks such intent at the time of the request, the inherent risk of the information being used for competitive purposes in the future cannot be denied as long as the competitive relationship (which the clause presupposes) exists.

- The purpose of this clause is to proactively prevent even the abstract danger of harm to the company. It achieves this by allowing the company to uniformly refuse inspection requests from shareholders who meet certain objective criteria (e.g., being a competitor themselves, or a shareholder/director of a competitor), irrespective of their specific, subjective intentions.

Therefore, the Supreme Court endorsed what legal scholars call the "no subjective requirement theory." For a company to invoke this ground of refusal, it is sufficient to establish the objective fact that the requesting shareholder falls into one of the categories listed (e.g., is a person who engages in a business that is in competition with the company, or is a member, shareholder, director, or executive officer of such a competing business). The shareholder's actual intent to misuse the information is not a necessary element. Consequently, a shareholder cannot overcome this refusal ground simply by attempting to prove their good intentions or lack of intent to misuse the information.

Application to the Applicant X: An Individual Assessment

Having established this strict interpretation, the Supreme Court then turned to X's specific situation:

- The Court noted that both X and Z individually met the statutory shareholding requirement in the parent company A (over 3% of voting rights) to qualify to request inspection of the subsidiary Y's books.

- Therefore, the existence of the objective facts constituting a refusal ground under Item 2 had to be assessed separately and individually for X and for Z.

- The mere fact that X and Z were mother and child and had applied for inspection jointly did not mean that a refusal ground applicable to one would automatically apply to the other.

Critically, the record showed that X herself was not a shareholder of B (the company in which Z was heavily involved and which was the potential competitor to Y) and was not an officer of B.

Based on this, the Supreme Court concluded that, without even needing to determine whether B was actually a competitor of Y or A, X did not objectively fall under any of the categories of persons for whom the competitor refusal clause (Art. 293-7 Item 2) would apply. She was not a competitor herself, nor was she a shareholder or officer of the alleged competitor B.

Thus, since X did not meet the objective criteria of the refusal clause, her request could not be denied on this basis. While the Supreme Court disagreed with the High Court's legal reasoning (particularly its adoption of the "presumed subjective intent" theory), it found that the High Court's ultimate conclusion to permit X's inspection was correct.

Analysis and Broader Implications

This Supreme Court decision has significant implications for how the "competitor" ground for refusing shareholder book inspection is understood and applied:

- Primacy of Objective Facts Over Subjective Intent: The ruling establishes a clear, bright-line rule for the competitor clause: objective status trumps subjective intent. If a shareholder objectively falls into a category defined by the statute (e.g., is a director of a competing company), the company can refuse inspection under this specific clause, and the shareholder's claims of benign intent will not overcome this. This provides a degree of certainty for companies.

- Individual Assessment in Joint Shareholder Requests: The Court's insistence on assessing X and Z individually is noteworthy. It signifies that in joint requests, the "taint" of one shareholder potentially falling under a refusal ground does not automatically disqualify other co-requesting shareholders if they, in their own right, meet the eligibility criteria and are not subject to any refusal grounds. This is a pro-shareholder aspect of the ruling, ensuring that an individual's rights are not curtailed solely due to their association with another requester. Legal commentary notes that some prior academic views suggested that if one joint requester had a refusal ground, the entire request could be jeopardized. This decision charts a different course.

- Reinforcement of the "No Subjective Requirement" Theory: The decision was a significant endorsement of the "no subjective requirement theory," which was the majority view among scholars under the old Commercial Code. The Court's reasoning – difficulty in proving intent, ongoing future risk despite present intentions, and the preventative nature of the clause – aligns with the traditional justifications for this theory.

- The Spectrum of Refusal Grounds: It's important to remember that the "competitor" clause is just one of several grounds for refusal (now listed in Companies Act Art. 433(2)). Other grounds, such as a request made to harm the company's operations or the common interests of shareholders (Art. 433(2) Items 1 and 2), do involve an assessment of the shareholder's purpose or intent. This ruling is specific to the competitor clause (Art. 433(2) Item 3), which, as the Court emphasized, is textually different.

- Context of Parent-Subsidiary Inspections: This case specifically dealt with a parent company shareholder seeking to inspect a wholly-owned subsidiary's books. Such requests require court permission (Companies Act Art. 433(3)), and the court cannot grant permission if any of the standard refusal grounds are present (Art. 433(4)). The Supreme Court's clarification thus directly impacts the criteria courts will use in these non-litigious permission proceedings.

- Evolving Definition of "Competitor"?: The commentary accompanying the case touches upon whether the definition of "persons engaged in a substantially competitive business" under the newer Companies Act might be interpreted more flexibly or substantially than the somewhat formalistic list in the old Commercial Code. If the focus shifts to a more nuanced assessment of actual competitive impact, the rationale for the "no subjective requirement theory" might become even stronger, as the objective assessment of "competition" itself would be more refined, reducing the need to delve into subjective intent. This Supreme Court decision, while under the old Code, sets a strong precedent for focusing on objective criteria for this specific refusal ground.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's January 15, 2009, decision provides a definitive statement on a contentious aspect of shareholder inspection rights. For the specific ground of refusal based on a shareholder's connection to a competitor, the Court has made it clear that the objective facts of that connection are paramount. A shareholder's subjective good intentions or lack of intent to misuse information will not override an objectively established status as a competitor or an affiliate of a competitor under this particular statutory provision. While ensuring that companies have a tool to protect themselves from potential harm through information leakage to competitors, the decision also upholds the principle that each shareholder's request, even when made jointly, should be assessed on its individual merits against these objective criteria.