The Chloroquine Tragedy in Japan: Supreme Court Addresses State Liability for Drug-Induced Retinopathy

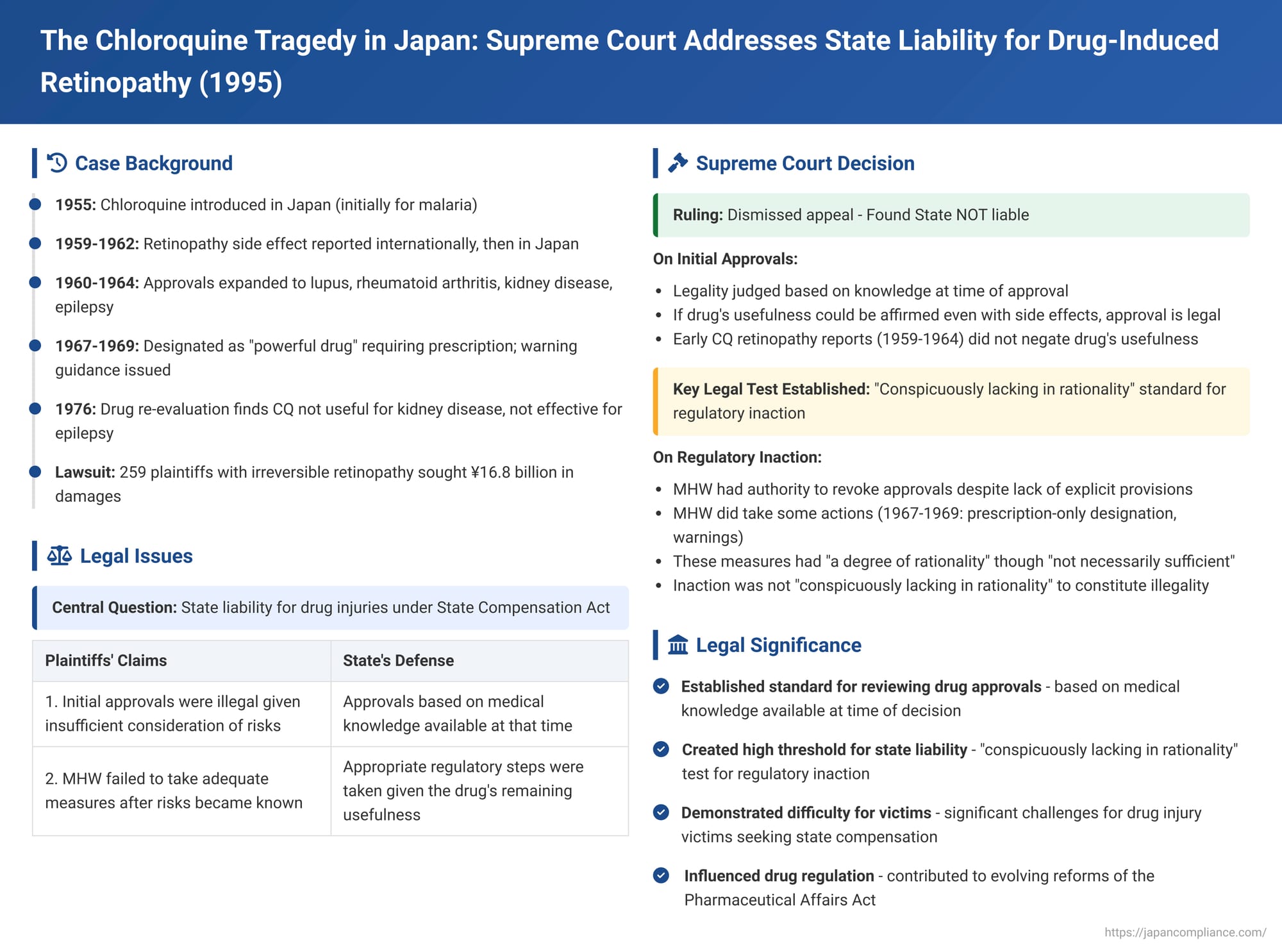

The devastating side effects of medications can lead to widespread human suffering and complex legal battles. One such significant case in Japan involved the drug Chloroquine (CQ), which, while used to treat conditions like malaria and rheumatoid arthritis, was found to cause an irreversible eye disease known as Chloroquine retinopathy. On June 23, 1995, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment (Heisei 1 (O) No. 1260) in a state compensation lawsuit brought by numerous victims, addressing the government's responsibility for the harm caused.

Chloroquine in Japan: Approvals, Use, and Emerging Dangers

Chloroquine, a drug developed in the 1930s, was introduced in Japan in 1955. Initially approved for malaria, its use was later expanded to treat lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and subsequently, even kidney disease and epilepsy.

However, a severe and irreversible side effect, Chloroquine retinopathy, began to be reported internationally in 1959. The first Japanese case was reported in 1962, and by 1965, information from major foreign medical literature and multiple domestic case reports were available. Despite these emerging concerns, the drug's overall usefulness was not initially negated, though it was recognized as a rare side effect associated with long-term use that required careful monitoring.

In response to increasing reports of CQ retinopathy, the Minister of Health and Welfare (MHW) took some regulatory steps. In 1967, CQ was designated as a "powerful drug" and a "drug requiring physician's instruction" (essentially a prescription drug). In 1969, through administrative guidance, the MHW instructed manufacturers to include warnings about long-term use in package inserts. It wasn't until a 1976 drug re-evaluation report that CQ was officially deemed not useful for kidney disease (due to side effects outweighing benefits) and not effective for epilepsy.

The lawsuit involved 259 plaintiffs, including patients who had taken CQ between 1959 and 1975 for various conditions (kidney disease, epilepsy, lupus, or rheumatoid arthritis) and subsequently developed Chloroquine retinopathy, as well as their heirs. They sued the Japanese State, six pharmaceutical companies, and several doctors and medical institutions, seeking approximately 16.8 billion yen in damages. (The claims against the pharmaceutical companies were eventually settled out of court after the High Court ruling).

The core of the claim against the State, under Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act, was twofold:

- That the MHW's initial manufacturing approvals and pharmacopoeia listings for CQ preparations, particularly for indications like kidney disease and epilepsy, were illegal given the (allegedly) insufficient consideration of its risks.

- That after these approvals, the MHW illegally failed to take adequate and timely measures (such as revoking approvals or issuing stronger warnings sooner) to prevent the widespread occurrence of CQ retinopathy. This is known as "failure to exercise regulatory authority" or regulatory inaction.

The Tokyo District Court had found the State liable for inaction but not for the initial approvals. The Tokyo High Court, however, denied State liability on both counts. The plaintiffs appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment (June 23, 1995): State Not Liable

The Supreme Court dismissed the plaintiffs' appeal, upholding the High Court's decision that found the State not liable.

On the Legality of Initial Approvals:

The Court laid down a standard for assessing the legality of drug approvals:

"In cases where the Minister of Health and Welfare lists a specific pharmaceutical product in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia or grants approval for its manufacture, if, under the medical and pharmaceutical knowledge at that time, the usefulness of the said pharmaceutical product can be affirmed even when considering its side effects, then the Minister's act of listing in the Pharmacopoeia, etc., should not receive an evaluation of illegality under Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act."

Applying this to Chloroquine, the Court noted that during the period of its key approvals and indication expansions (1960-1964), reports concerning CQ retinopathy were only beginning to emerge internationally and domestically. The content of these early reports, according to the Court, pointed to the risk of irreversible retinal damage from long-term use and the need for regular eye examinations, but did not negate the overall usefulness of CQ. With only a small number of cases reported in Japan during this initial period (seven by 1964), the Court concluded: "Under the medical and pharmaceutical knowledge at that time based on these documents and case reports, there was no illegality in the said acts by the Minister of Health and Welfare in affirming the usefulness of Chloroquine preparations for the aforementioned respective diseases, including kidney disease and epilepsy."

(The PDF commentary critiques this finding, particularly for kidney disease and epilepsy, arguing that the severity of the side effect, lack of international precedent for these uses, and emerging domestic cases should have led to a different risk-benefit assessment by the MHW even at that early stage. )

On Regulatory Inaction (Failure to Act Post-Approval):

The Supreme Court then addressed the claim that the MHW had illegally failed to take appropriate action after CQ was on the market and more information about its side effects became known.

- MHW's Power to Act Post-Approval: The Court affirmed that even under the 1960 Pharmaceutical Affairs Act (which lacked explicit provisions for revoking approvals for safety reasons, unlike later revisions), the MHW did possess the authority to remove a drug from the Japanese Pharmacopoeia or revoke its manufacturing approval. This power was derived from the overall purpose of the Act and the MHW's initial authority regarding drug safety and approval.

- Standard for Illegal Inaction: The Court established a high threshold for when such inaction becomes legally culpable: "Even if damage due to the side effects of a pharmaceutical product occurs, the fact that the Minister of Health and Welfare did not exercise the aforementioned respective powers to prevent the occurrence of damage due to the side effects of the said pharmaceutical product is not immediately evaluated as illegal under Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act. Rather, it is when, under the medical and pharmaceutical knowledge at that point in time regarding the said pharmaceutical product including its side effects, and in light of the aforementioned purpose of the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act and the nature of the powers vested in the Minister of Health and Welfare, etc., the non-exercise of said powers deviates from the permissible limits and is found to be conspicuously lacking in rationality (ichijirushiku gōrisei o kaku), that such non-exercise becomes illegal under the said paragraph in relation to those who suffered damage from the side effects."

- Application to Chloroquine: The Court found that, based on the medical and pharmaceutical knowledge available at the time, the usefulness of Chloroquine had not been negated to the extent that would make the MHW's failure to revoke its approval or remove it from the pharmacopoeia "conspicuously lacking in rationality." It pointed to the fact that even after CQ retinopathy became known, CQ was still considered useful for lupus and rheumatoid arthritis internationally and, until the 1976 re-evaluation, for kidney disease and epilepsy in Japanese clinical practice, albeit with recognized risks.

Furthermore, the Court noted that the MHW had taken certain regulatory actions from 1967 onwards, such as designating CQ as a powerful drug and a prescription-only drug, and issuing administrative guidance for warnings to be included in package inserts. While acknowledging that these measures, in hindsight and particularly after the 1976 re-evaluation, "cannot be said to have been necessarily sufficient in their content and timing," the Court found that "under the medical and pharmaceutical knowledge at that time, the said measures taken by the Minister of Health and Welfare can be evaluated as having a degree of rationality in their purpose and means."

Therefore, the MHW's failure to take further action beyond these measures was not deemed "conspicuously lacking in rationality" to the point of being illegal under the State Compensation Act.

(The PDF commentary strongly criticizes this application of the standard, arguing that given the known severity of CQ retinopathy, the limited efficacy for certain conditions like kidney disease and epilepsy, and the ineffectiveness of the initial regulatory steps, the failure to act more decisively, such as by revoking approvals for problematic indications much earlier than 1976, did conspicuously lack rationality. )

Key Legal Principles Established or Affirmed

The Chloroquine Retinopathy judgment is a landmark case in Japanese administrative and pharmaceutical law for several reasons:

- Standard for Reviewing Drug Approvals: It affirmed that the legality of an initial drug approval decision by the MHW is to be judged based on the scientific and medical knowledge available at the time of that decision. The core test is whether the drug's usefulness could be affirmed, even considering its known side effects, under the then-prevailing knowledge.

- State's Duty Regarding Post-Market Drug Safety and the "Conspicuously Lacking in Rationality" Test: The decision established a significant precedent for state liability concerning regulatory inaction for drugs already on the market. It confirmed that the MHW has powers (including implicit ones like revocation under older laws) to address post-approval safety issues. However, a failure to exercise these powers only becomes illegal state action if it is "conspicuously lacking in rationality." This high threshold has become a leading standard in assessing state liability for regulatory negligence in Japan.

The Aftermath and Broader Implications for Drug Safety

The Chloroquine case was one of Japan's major "drug injury" (yakugai) lawsuits, profoundly impacting victims and highlighting systemic issues in drug safety oversight.

- It underscored the critical importance of robust post-marketing surveillance systems and the need for timely, decisive regulatory action when new drug risks emerge or when the risk-benefit balance for existing drugs changes.

- The "conspicuously lacking in rationality" standard, while providing a basis for potential state liability, has often been criticized by plaintiffs and some legal scholars as setting an excessively high bar, making it very difficult to hold regulatory authorities accountable for failures in oversight.

- The case also played a role in the broader evolution of Japan's Pharmaceutical Affairs Act, with subsequent revisions aiming to strengthen safety measures, clarify ministerial powers, and improve the drug approval and post-marketing surveillance processes.

Conclusion

In the Chloroquine Retinopathy State Compensation Claim Case, the Supreme Court of Japan ultimately found the State not liable for the widespread harm caused by the drug. The Court's decision emphasized that the legality of initial drug approvals must be assessed based on the scientific knowledge available at that time, and that subsequent failure by regulatory authorities to act against a marketed drug only incurs state liability if such inaction is deemed "conspicuously lacking in rationality." While this judgment provided important legal standards, particularly for regulatory inaction, it also highlighted the significant challenges faced by victims of pharmaceutical side effects in seeking compensation from the state, and it continues to be a focal point for discussions on drug safety and regulatory accountability in Japan.