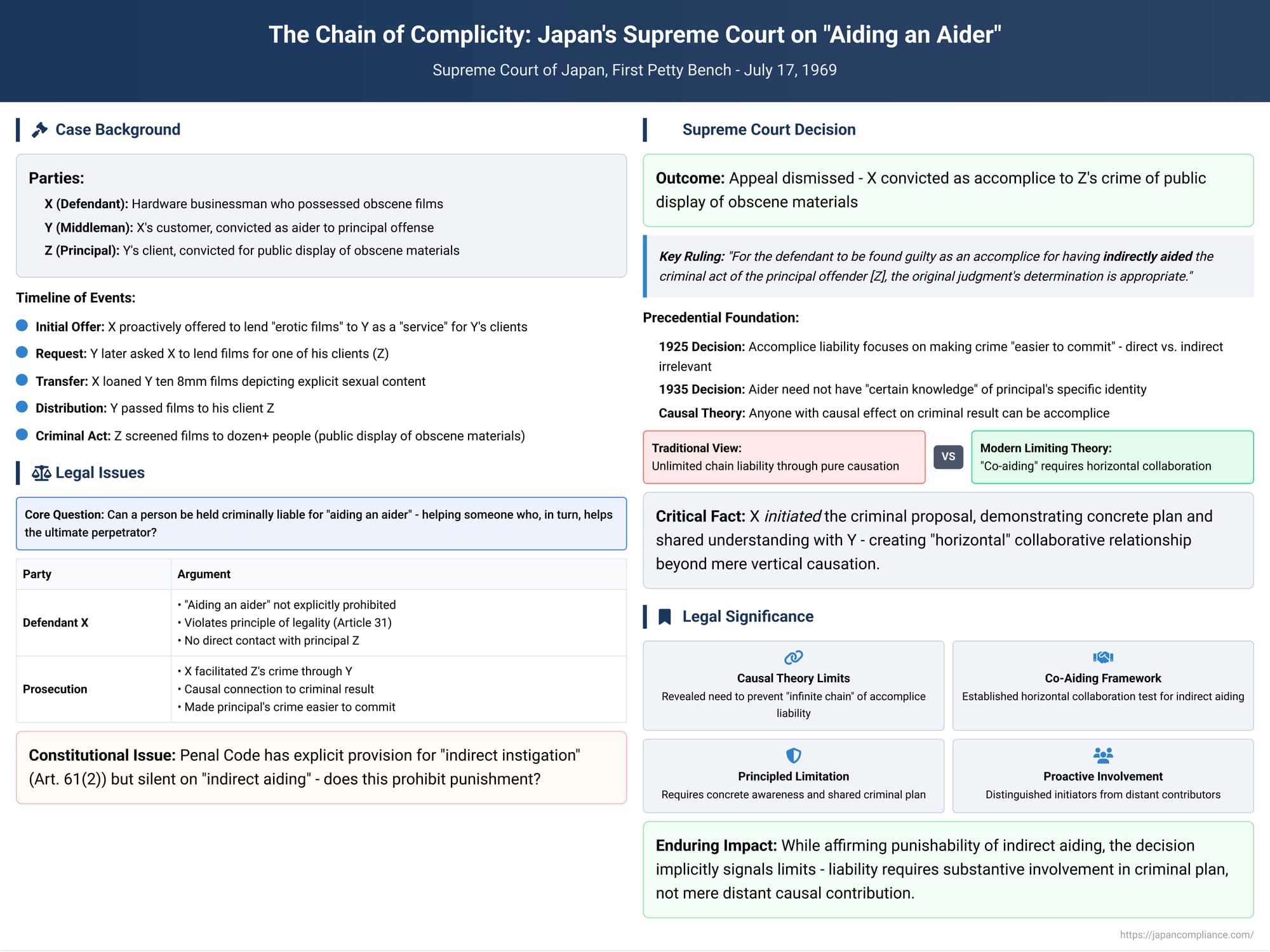

The Chain of Complicity: Japan's Supreme Court on "Aiding an Aider"

Decision Date: July 17, 1969

Case Number: 1968 (A) No. 1889

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

Accomplice liability is a cornerstone of criminal law, ensuring that those who assist in a crime are also held accountable. But how far does this chain of responsibility extend? Is an individual criminally liable for helping someone who, in turn, helps the ultimate perpetrator of a crime? This question of "indirect aiding and abetting"—or, more colloquially, "aiding an aider"—was the subject of a foundational ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan on July 17, 1969.

The case involved the lending of obscene films through a middleman. While the facts may seem dated, the legal principles articulated by the Court continue to shape the understanding of complicity in Japanese law. The decision affirmed that an individual can be convicted for indirectly facilitating a crime, even without direct contact with the principal offender, but the underlying reasoning reveals a nuanced approach that seeks to prevent an unlimited and unjust expansion of criminal liability.

Factual Summary

The case concerned three individuals involved in the distribution and display of obscene materials. For clarity, we will refer to them as X, Y, and Z.

- The Parties:

- Defendant X was a businessman engaged in the manufacture and sale of architectural hardware.

- Y was a customer of X. He was ultimately convicted as an aider in the principal offense.

- Z was a client of Y. He was convicted as the principal offender for the crime of public display of obscene drawings (under Article 175 of the Penal Code).

- The Sequence of Events:

- The chain of events began with an offer from X to his customer, Y. X mentioned to Y that he possessed "erotic films" and offered to lend them at any time if Y wanted to use them as a "service" for his own clients.

- At a later date, Y accepted the offer, asking X to lend him the films so he could provide them to one of his clients. Y did not mention the client's specific name, Z, at the time of the request.

- X then loaned Y ten 8mm film reels that explicitly depicted scenes of sexual intercourse.

- Y, acting as an intermediary, passed the films to his client, Z.

- Z subsequently screened the films for a group of more than a dozen people, thereby committing the principal offense of public display of obscene material.

The lower courts convicted X for aiding and abetting Z's crime. The first-instance court controversially described X's act as "directly aiding" Z, despite the lack of direct contact. The appellate court found this description improper but deemed the error immaterial to the verdict and upheld the conviction. X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Question: "Aiding an Aider" and the Principle of Legality

The core of X's defense on appeal was a direct challenge to the legal basis of his conviction. His argument centered on two key points:

- Aiding an Aider: X's actions directly facilitated the crime of Y (who was himself an aider). He did not directly facilitate the crime of Z (the principal offender). The defense argued this constituted "aiding an aider" (hōjo no hōjo), a form of complicity not explicitly defined or prohibited by the Penal Code.

- Principle of Legality: The defense contended that punishing an act not explicitly outlawed by statute violates the principle of legality (zaikei hōtei shugi), a fundamental concept enshrined in Article 31 of the Japanese Constitution. The Penal Code contains a specific provision for "indirect instigation" (instigating an instigator) in Article 61(2), but it is silent on "indirect aiding". The defense argued this silence should be interpreted as a deliberate choice by the legislature not to criminalize such conduct.

The Supreme Court's Decision and Precedent

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal and affirmed X's conviction. In its characteristically brief reasoning, the Court stated:

"...regarding the present case, in which the defendant, knowing that [Y] or his client would have an unspecified number of people view them, loaned the obscene films in question to said [Y], and the films were then loaned from [Y] to his client [Z], whereupon [Z] projected them for a dozen or so people to view and publicly displayed them; for the defendant to be found guilty as an accomplice for having indirectly aided the criminal act of the principal offender [Z], the original judgment's determination is appropriate."

This conclusion, while decisive, was not novel. The Court was acting on a line of precedent that had long accepted the punishability of indirect aiding.

- Taisho 14 (1925) Decision: An earlier top court ruling had established that the reason for punishing accomplices is that they make the principal's crime easier to commit. Therefore, it is irrelevant "whether the act of aiding is direct or indirect" in relation to the principal's act.

- Showa 10 (1935) Decision: Another key precedent, citing the 1925 ruling, added that in cases of indirect aiding, it is "not necessary for the aider to have certain knowledge of by what person the principal offense will be carried out." The core issue is the facilitation of the crime, not the aider's knowledge of the principal's specific identity.

Deeper Dive: Competing Theories and Limiting Liability

The precedents firmly establish that indirect aiding is punishable, but they leave open a critical theoretical question: where does liability end?

The traditional theory underpinning these rulings is the Causal Theory of Complicity (inga-teki kyōhan-ron). This view posits that anyone who has a causal effect on the final criminal result can be held liable as an accomplice. From this perspective, X's liability is straightforward: by providing the films, he set in motion a chain of events that causally led to Z's public screening.

However, this theory has a significant flaw: it could lead to an "infinite chain" of liability. If X is liable for aiding Y, would someone who aided X also be liable? This potential for an endless expansion of punishment (shobatsu no hidaika, or "bloating of punishment") is considered inappropriate and contrary to the purpose of accomplice law.

More modern legal theory seeks to reasonably limit the scope of accomplice liability. Rather than focusing solely on cause-and-effect, it looks for a more substantial connection. One influential concept for achieving this is "Co-Aiding" (kyōdō hōjo), which is sometimes referred to as joint perpetration of the act of aiding (hōjo-han no kyōdō seihan).

This model analyzes the relationships between the parties:

- A "vertical" (tate) relationship describes the linear chain: X aids Y, who in turn aids Z.

- A "horizontal" (yoko) relationship exists when the indirect aider (X) and the direct aider (Y) are essentially on the same level, working in concert to help the principal (Z).

For an indirect aider to be held liable under this more restrictive view, there must be evidence of this horizontal, collaborative relationship. The key test is whether the indirect aider had a sufficiently precise awareness of the concrete circumstances and plan of the principal crime. This requires more than just a vague notion that something illegal might happen; it demands a shared understanding of the criminal project.

The Enduring Significance of the 1969 Decision

Viewed through this modern analytical lens, the 1969 Supreme Court decision takes on a deeper significance. While the ruling broadly affirms the punishability of indirect aiding, the specific facts of the case provide a basis for a more limited and principled interpretation.

The crucial fact, noted by the lower courts, is that X himself initiated the criminal proposal. He was the one who first told Y he had films and suggested Y could use them to "service" clients. This proactive offer demonstrates that X had a concrete and specific plan in mind for how the films would be used, even if he did not know the ultimate user's name.

This element of proactive planning and shared understanding creates the "horizontal" link between X and Y. They were not merely two separate links in a causal chain; they were, in substance, "co-aiders" working toward the same criminal goal: the public display of the films. It was this substantive collaboration that justified holding X liable as Z's accomplice.

Therefore, the decision's true importance lies not in opening the door to limitless liability, but in implicitly signaling where the line should be drawn. It teaches that indirect aiding is punishable when the indirect aider is not a distant, detached contributor but is substantively involved in the criminal plan. The ruling correctly avoids the flawed logic that "a friend of a friend is always a friend," preventing an endless chain of complicity while holding those who are knowingly and purposefully involved in a criminal enterprise accountable.