The Case of the Counterfeit Coupon: A Deep Dive into Japan's "Mistake of Law" Doctrine

Decision of the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan, July 16, 1987.

Case No. (A) 457 of 1985: Violation of the Currency and Securities Imitation Control Act

Introduction

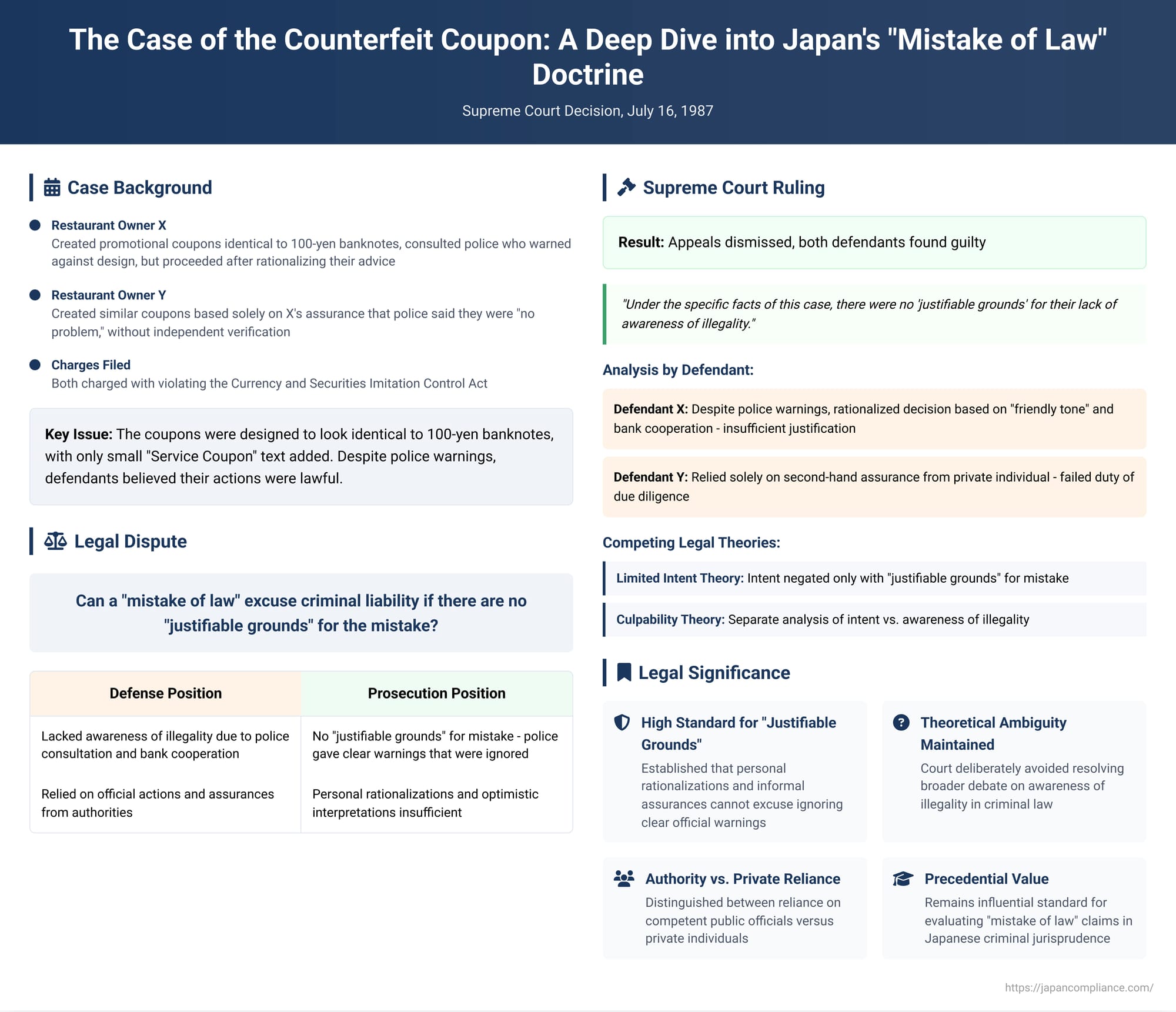

In the landscape of Japanese criminal law, few concepts are as debated and nuanced as the "awareness of illegality" (ihōsei no ishiki). The principle questions whether a person can be held criminally liable if they genuinely believed their actions were lawful. A pivotal case that brought this issue to the forefront is a 1987 Supreme Court decision involving two restaurant owners who created promotional coupons designed to look remarkably like 100-yen banknotes.

This case, while seemingly straightforward, peels back the layers of Japanese legal theory on criminal intent (kōi) and culpability (sekinin). It provides a fascinating look into how the Japanese courts evaluate a defendant's state of mind and the circumstances under which a "mistake of law" might—or might not—excuse a criminal act. The court’s detailed examination of the defendants' interactions with police and their own justifications offers a compelling narrative on the boundaries of good faith and negligence in the eyes of the law.

The Factual Background

The case centered around two individuals, referred to here as X and Y.

Defendant X's Actions

X was the operator of a restaurant and, in an effort to promote his business, conceived of a novel promotional tool: a "service coupon." He commissioned a printing company to produce coupons that, on their face, were identical in size, design, and general color scheme to the 100-yen banknote issued by the Bank of Japan. The only textual additions were the words "Service Coupon" printed in small red letters in two locations on the top and bottom. The reverse side of the coupon was dedicated to advertising for his restaurant.

Before proceeding, the printing company itself raised a concern, suggesting that producing a coupon so closely resembling one side of a genuine banknote might be problematic. This prompted X to seek advice. He visited a local police station to consult with a police officer he knew. This officer and the head of the crime prevention section were present for the consultation.

During the meeting, the police officers showed X the relevant statute, the Currency and Securities Imitation Control Act, and explicitly warned him that creating items that could be confused with real currency was a violation of the law. They advised him on how to avoid illegality: he could, for instance, make the coupons significantly larger than a real banknote or clearly print words like "Sample" or "Service Coupon" in a way that would leave no room for confusion.

However, X's interpretation of this encounter was colored by several factors. He perceived the officers' tone as friendly and their advice as suggestive rather than a strict, categorical prohibition. He felt they were not issuing a direct order. This impression was compounded when a deputy manager at his bank, upon hearing X's plan to distribute the coupons, readily agreed to his request to wrap the stacks of coupons in the bank's official paper bands (obi).

X rationalized his decision to proceed with the original design. He reasoned that the 100-yen banknote was no longer in common circulation at the time (its issuance had been suspended years earlier, in 1974). He also believed that since the reverse side clearly contained advertising, looking at the coupon as a whole would dispel any confusion with real currency. While he did heed the printing company's subsequent advice to add the small "Service Coupon" text, he ultimately dismissed the police officers' more substantial recommendations. He optimistically concluded that he was unlikely to be punished for creating the coupons and went ahead with the first printing.

After receiving the first batch of coupons, X had them wrapped in the bank's official bands. He then took a bundle of about 100 coupons to the same police station and presented them to the officers he had consulted. He received no particular warning or admonition. On the contrary, the officer he knew found them novel and even began distributing them to others in the room. This reaction greatly reassured X. Feeling confident that his actions were permissible, he proceeded to commission a second, similar batch of coupons. For this second batch, he made minor changes, replacing the serial number with his restaurant's phone number and changing the "Bank of Japan Note" text to "[Restaurant Name] Note."

X's main purpose in bringing the coupons to the police station was not to seek a final, formal approval of their legality but rather as a promotional activity to encourage the officers to visit his establishment.

Defendant Y's Actions

Defendant Y, who was involved in the management of another restaurant, saw the coupons X had created and decided he wanted to produce similar ones for his own business. He approached X, who gave him his blessing. Y then commissioned the same printing company to create coupons with the same design. He similarly replaced the serial number and bank name with his restaurant's phone number and name, respectively.

Before doing so, Y had a conversation with X. X told him that the police had said the coupons were "no problem," despite their resemblance to the 100-yen note. X added that a significant amount of time had passed since he had distributed them to the police and no issues had arisen. He also mentioned that the bank had wrapped them for him. Given that the 100-yen note was rarely seen in public, Y did not feel any particular anxiety. He proceeded with creating the coupons without conducting any independent investigation or inquiry into their legality. He relied entirely on X's story and assurances.

The Rulings of the Courts

The District Court and the High Court both found X and Y guilty of violating the Currency and Securities Imitation Control Act. The core of their reasoning was that while the defendants may have lacked an awareness of the illegality of their actions, their mistake was not based on "justifiable grounds" (sōtō no riyū).

The defendants appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

On July 16, 1987, the Supreme Court upheld the lower courts' decisions and dismissed the appeals. The Court's reasoning was precise and carefully worded. It acknowledged the defendants' claim that they lacked an awareness of illegality. However, it concluded that under the specific facts of this case, there were no "justifiable grounds" for their lack of awareness.

Critically, the Supreme Court stated that its conclusion made it unnecessary to delve into and decide upon the broader legal principle of whether a crime is negated if the lack of awareness of illegality is, in fact, based on justifiable grounds. In other words, the Court found that even if it were to adopt the more lenient legal theory favored by the defendants, the facts of their case were simply not strong enough to support an acquittal. It held that the guilty verdict of the lower courts was correct regardless of which overarching legal doctrine was applied.

Legal Analysis: Unpacking the Doctrine of "Mistake of Law"

This case serves as a masterclass in the Japanese legal debate over "mistake of law." To understand the Supreme Court's delicate maneuvering, one must first appreciate the competing legal theories that have vied for dominance in Japanese jurisprudence.

The Central Issue: Awareness of Illegality (Ihōsei no Ishiki)

In Japanese criminal law, for most crimes, conviction requires proof of kōi, or intent. At its most basic, this means the defendant must have recognized the facts constituting the crime. The more complex question is whether kōi also requires an "awareness of illegality"—a recognition that the act is legally prohibited. If a defendant truly believes their act is lawful, can they be found guilty?

This question has given rise to several distinct schools of thought:

- The Theory of Irrelevance: The traditional, historical position of the Supreme Court was that a defendant's subjective awareness of illegality is irrelevant to whether a crime was committed. As long as the defendant intended to commit the act itself, their ignorance of its illegality was no defense. This view, however, has been widely criticized by legal scholars for being too harsh and potentially violating the principle of culpability, which holds that a person should not be punished unless they are blameworthy.

- The Strict Intent Theory (Genkaku Koi Setsu): At the other end of the spectrum, this theory argues that a genuine awareness of illegality is a necessary component of criminal intent (kōi). If this awareness is missing, for whatever reason, intent is negated, and no crime is committed. Critics argue this standard is too lenient and could lead to acquittals for individuals who were merely negligent in learning the law.

- The Limited Intent Theory (Seigen Koi Setsu): A more moderate position, this theory holds that for intent to be established, it is sufficient that the defendant had the possibility of recognizing the act's illegality, even if they didn't have actual, concrete awareness. This theory softens the Strict Intent Theory by preventing defendants from easily escaping liability by claiming ignorance when they should have known better. Many lower court decisions in Japan have implicitly or explicitly adopted this view, stating that intent is negated only when there are "justifiable grounds" for the mistake of law.

- The Culpability Theory (Sekinin Setsu): This is the predominant view among legal scholars today. It separates intent from the awareness of illegality. Under this theory, intent relates only to the facts of the act. The awareness of illegality (or its possibility) is treated as a separate element of culpability. If a person acts without the possibility of recognizing their act's illegality, they are not considered blameworthy, and their culpability is negated, leading to an acquittal. While the outcome is often the same as the Limited Intent Theory (acquittal only if the mistake is unavoidable), the conceptual framework is different.

The Supreme Court’s Position: A Deliberate Ambiguity

Prior to this 1987 decision, there were signs that the Supreme Court was moving away from its traditional, rigid "Theory of Irrelevance." In several high-profile cases in the 1970s and early 1980s, the Court had taken the time to explicitly find that the defendants did have an awareness of illegality, a step that would have been unnecessary if such awareness were truly irrelevant. This led to widespread anticipation that the Court was waiting for the right case to formally change its precedent.

The coupon case seemed like it could be that opportunity. However, the Court chose to sidestep the issue. By focusing narrowly on the absence of "justifiable grounds," it reached a conclusion that was consistent with both the Limited Intent Theory and the Culpability Theory, without having to officially adopt either one. The Court essentially said: "We don't need to decide today which theory is correct, because under any plausible modern theory, these defendants lose."

This strategic reservation is significant. It signals that the Court recognized the shortcomings of the old doctrine and was open to re-evaluation, but it was not yet prepared to commit to a specific new framework.

What Constitutes "Justifiable Grounds" (Sōtō no Riyū)?

The crux of the decision, then, is the Court's analysis of "justifiable grounds." This term refers to a situation where it would be unreasonable to blame the actor for not knowing their conduct was illegal. The Court's findings for each defendant are illuminating.

- Analysis of Defendant X: X's defense was perhaps the more compelling of the two, yet the Court found it lacking. The key factor was that he had received direct, specific, and accurate advice from a competent public authority—the police—and had chosen to disregard it. His justifications for doing so were deemed insufficient.The Court did acknowledge the events after the first printing, where the police accepted the coupons without protest. Some commentators have argued that this positive reinforcement from the police could have established justifiable grounds for X's second act of printing. They might have reasonably, if mistakenly, concluded that their design had been tacitly approved. However, the Court ultimately did not accept this, likely viewing the entire course of conduct as stemming from the initial, unjustified decision to ignore the police's advice.

- The "Friendly Tone" of the Police: The Court was unmoved by the claim that the officers' manner was not "assertive." Legal advice from law enforcement does not need to be delivered as a threat to be valid.

- The Bank's Cooperation: The bank's willingness to wrap the coupons was irrelevant to their legality under the Currency Imitation Control Act. A bank's customer service gesture does not constitute a legal opinion.

- Personal Rationalization: X's own beliefs about the 100-yen note's circulation or the effect of the advertising on the back were simply his own optimistic interpretations. They could not override the explicit guidance he had received.

- Analysis of Defendant Y: Y's case was far weaker. His mistake of law was based almost entirely on the second-hand assurances of X, a private citizen. The Court found that he had a duty to conduct his own due diligence. He could have easily consulted the police or another authority himself. Relying on the word of a business acquaintance, even one who claimed to have checked with the authorities, was deemed negligent. This illustrates a clear principle: while reliance on a definitive statement from a competent public official can sometimes create "justifiable grounds," reliance on a private individual almost never will.

Conclusion

The 1987 "counterfeit coupon" decision remains a landmark ruling in Japanese criminal law. It provides a detailed and practical application of the "mistake of law" doctrine, demonstrating the high bar a defendant must clear to successfully argue that their ignorance of the law should be excused.

The Court’s analysis of "justifiable grounds" sends a clear message: subjective optimism, personal rationalizations, and reliance on the informal actions or opinions of others are not sufficient to excuse an illegal act, especially when clear, authoritative advice has been given and ignored. While the Supreme Court deliberately left the larger theoretical debate on awareness of illegality unresolved—a debate that continues to this day—its practical holding in this case established a durable and influential standard for how such claims are to be evaluated in practice. It underscores the principle that while the law may, in very narrow circumstances, forgive an honest and unavoidable mistake, it will not excuse a mistake born of convenience, optimism, or a failure to take legal obligations seriously.