The Bribe That Was Embezzled: A Japanese Ruling on Property, Crime, and "Illegal Cause"

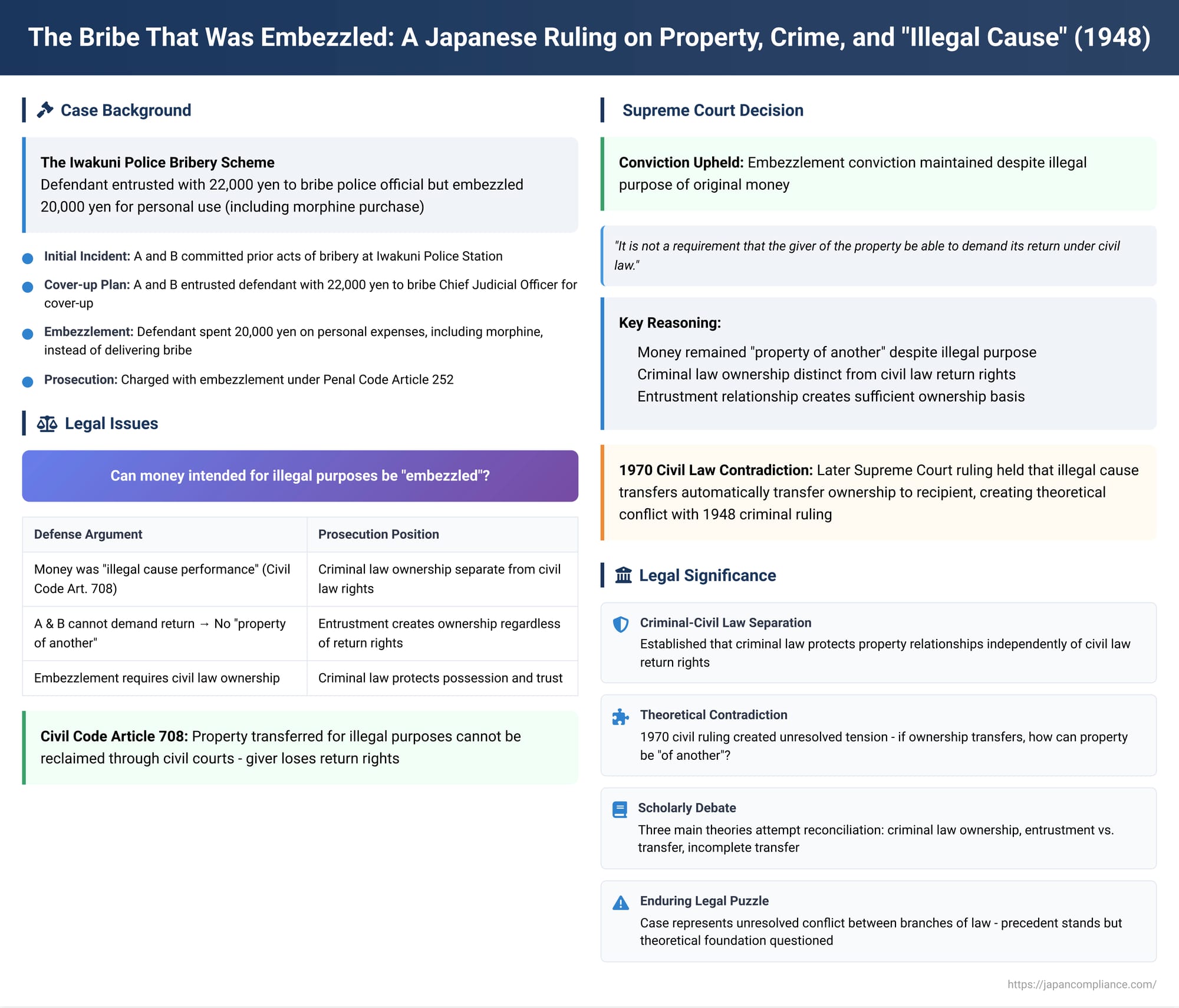

Imagine a person gives an intermediary a sum of money with a clear, but illegal, instruction: use this cash to bribe a public official. The intermediary, however, instead of delivering the bribe, pockets the money and spends it on themselves. Can this person be convicted of the crime of embezzlement? The question creates a fascinating legal paradox. If the money was intended for an illegal purpose, does the original owner have any right to it that the criminal law should protect?

This complex problem, which lies at the intersection of civil and criminal law, was the subject of a foundational decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on June 5, 1948. The Court's ruling, while establishing a precedent that has stood for decades, has been the subject of intense scholarly debate ever since a subsequent civil law decision appeared to undermine its very foundation. The case provides a deep insight into the legal concept of ownership and the limits of criminal law in policing illicit transactions.

The Civil Law Doctrine: "Performance for an Illegal Cause"

To understand the case, one must first understand a key principle of Japanese civil law found in Article 708 of the Civil Code: the doctrine of "performance for an illegal cause" (fuhō gen'in kyūfu). This doctrine states that a person who gives property to another for a purpose that is illegal or contrary to public policy cannot later sue in a civil court to demand its return.

For example, if someone gives another person money to commit a crime, and the person fails to do so, the original giver cannot use the court system to get their money back. The law essentially refuses to assist parties with "unclean hands." This raises a critical question for criminal law: if the civil law will not protect such property, should the criminal law?

The Facts of the Case: The Embezzled Bribe

The defendant in the case was entrusted with 22,000 yen by two individuals, A and B. The money was given for a specific and illegal purpose: to bribe A and B's superior, the Chief Judicial Officer of the Iwakuni Police Station, in order to cover up their own prior acts of bribery.

The defendant was instructed to hold the money and use it for the bribe. Instead of delivering the bribe, however, he spent 20,000 yen of it on his own personal expenses, including purchasing morphine.

He was charged with and convicted of embezzlement. On appeal, his defense lawyer presented a powerful argument based on civil law. He contended that the money was a "performance for an illegal cause." Therefore, under Civil Code Article 708, the givers, A and B, had no legal right to demand its return. Since they had no right to get the money back, the defendant was effectively in a position to dispose of it freely, and his spending it on himself could not constitute the crime of embezzlement.

The 1948 Supreme Court's Ruling: Criminal Law Stands Separate

The Supreme Court rejected the defendant's argument and upheld the embezzlement conviction. The Court's reasoning drew a sharp line between the requirements of civil law and criminal law.

The Court held that the crime of embezzlement, under Article 252 of the Penal Code, requires that the object be "property of another" that is in the offender's possession. It then stated its core principle:

"...it is not a requirement that the giver of the property be able to demand its return under civil law."

The Court reasoned that since the defendant received the money for the specific purpose of bribing someone else, "it cannot be said that the money... is the defendant's property." It remained the "property of another," and therefore, spending it for his own purposes constituted embezzlement, regardless of whether A and B could have successfully sued him. The Court's decision was based on the premise that even if the right to demand return was lost, the underlying ownership of the money remained with the givers.

The Plot Twist: The 1970 Civil Law Revolution

For nearly two decades, the 1948 ruling stood as clear law. However, in 1970, the Supreme Court issued a landmark decision in a civil case that created a direct theoretical conflict. The 1970 civil ruling established that when property is transferred for an illegal cause, ownership itself actually transfers to the recipient. This transfer is a "reflexive effect" of the giver's inability to demand the property back.

This created a major problem for the 1948 criminal ruling. If ownership of the bribe money legally transferred to the defendant the moment he received it, then the money was no longer the "property of another." If it was his own property, it would be theoretically impossible for him to embezzle it. The 1970 civil decision seemed to completely invalidate the legal reasoning of the 1948 criminal decision.

Reconciling the Irreconcilable: Scholarly Theories

This contradiction has led to decades of scholarly debate, with legal experts proposing various theories to explain how the conclusion of the 1948 case (that embezzling a bribe is a crime) can still be justified.

- The "Criminal Law Ownership" Theory: This view argues that ownership in criminal law can be defined differently from ownership in civil law. Even if civil law says ownership has transferred, criminal law can still treat the property as belonging to "another" for the purpose of preventing crime. However, most scholars criticize this theory for creating an incoherent legal system.

- The "Entrustment vs. Final Transfer" Theory: This popular theory argues that the "illegal cause" doctrine only applies to a "final transfer" (kyūfu) of property. It claims that when A and B gave the money to the defendant, it was merely an "entrustment" (itaku) to an intermediary. The intended "final transfer" was to the police official. Since the entrustment was not the final transfer, ownership did not yet pass to the defendant. While clever, this theory is difficult to square with other cases where courts have treated entrustment for illegal purposes as a final transfer.

- The "Incomplete Transfer" Theory: This theory focuses on when the "illegal cause" transfer is completed. It argues that the transfer is not just the handing of money to the intermediary, but the entire act of bribery. Since the money never reached the police official, the illegal act was never completed. Therefore, Civil Code Article 708 was never triggered, ownership never passed to the defendant, and he could be guilty of embezzlement. A major critique of this view is that it might actually encourage bribery, as it implies a giver could demand their money back at any point before the bribe is paid, creating a "safety valve" for failed bribery attempts.

Conclusion: An Enduring Puzzle in Japanese Law

The 1948 Supreme Court decision on embezzling bribe money remains the leading criminal law precedent on the books. However, it exists in a state of unresolved theoretical tension with the 1970 civil law ruling on ownership.

While legal scholars have devised ingenious theories to reconcile the two, the dominant view today is that the 1948 ruling, while perhaps reaching a just result, is no longer theoretically sound. Many argue that if a similar case were to reach the Supreme Court today, the Court would be forced to confront the 1970 civil law precedent, which could lead to the conclusion that embezzling funds given for an illegal cause is not a crime. The case stands as a fascinating example of how different branches of law can evolve in ways that create profound and enduring legal puzzles.