The Borrower as Co-Conspirator: A Japanese Ruling on Liability in Improper Lending

In a typical loan transaction, the lender and the borrower are on opposite sides of the table, each pursuing their own company's best interests. If a bank's executives, in a foolish and disloyal act, approve a reckless loan to a company, they may be guilty of the crime of "breach of trust" against their own bank. But what about the borrower? If the company that receives the loan knows the lending decision is improper, can its executives be held criminally liable as co-conspirators in the lender's crime?

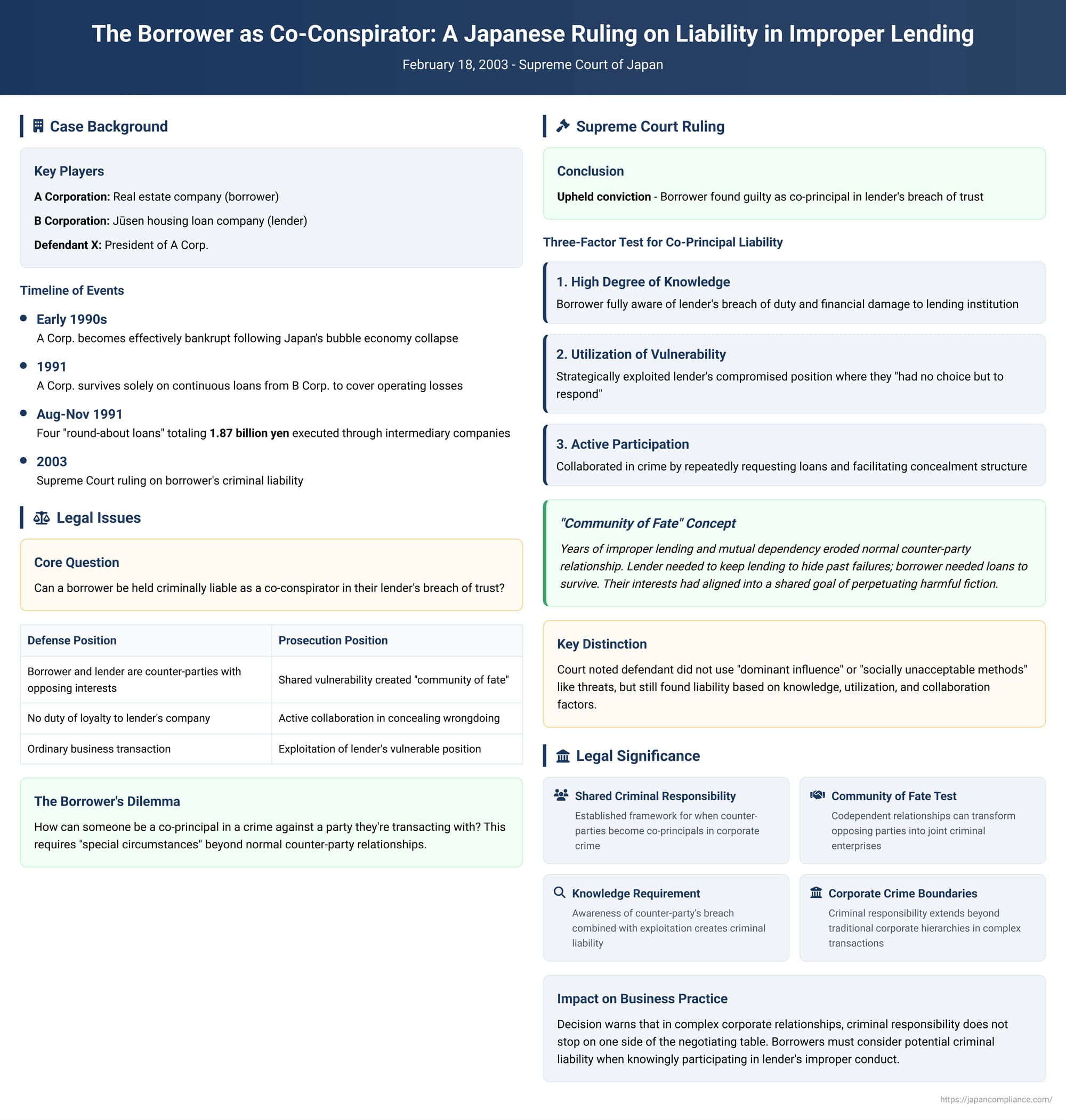

This question, which probes the complex boundaries of corporate crime and complicity, was the subject of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on February 18, 2003. The case, arising from the bad-loan crisis that plagued Japan's "bubble economy," established a crucial test for when a borrower crosses the line from a mere counter-party to a co-principal in their lender's breach of trust. The Court found that when a codependent relationship transforms the two parties into a "community of fate," shared criminal responsibility is possible.

The Facts: The "Jūsen" Crisis and the Endless Loans

The case involved A Corporation, a real estate company, and its primary lender, B Corporation, a major jūsen (housing loan corporation). The defendant, X, was the president of A Corp.

By the early 1990s, following the collapse of Japan's bubble economy, A Corp. was in a dire financial state. It was effectively bankrupt, unable to secure financing from any institution other than B Corp., and was surviving solely on a continuous stream of new loans from B Corp. that were used to cover its operating losses.

The executives at the lender, B Corp., led by their president, Z, were fully aware of this situation. They knew A Corp. was insolvent and that any new loans were almost certain to be unrecoverable. However, they were trapped. If they cut off funding, A Corp. would immediately collapse, forcing B Corp. to realize its own massive, unrecoverable loans and exposing the executives to legal responsibility for their past reckless lending.

To protect themselves and postpone the inevitable, Z and his team continued to prop up A Corp. To hide the true extent of their exposure, they funneled the money through a series of "round-about loans" (ukai yūshi), using related companies as intermediaries. Between August and November of 1991, they executed four such loans totaling 1.87 billion yen.

The defendant, X, as the president of the borrowing company, was intimately involved. The Court found that:

- He had a "high degree of knowledge" that his company was insolvent and that the loans from B Corp. constituted a breach of the B Corp. executives' duties to their own company.

- He knew the B Corp. executives were acting out of a desire for "self-preservation" and were in a situation where they "had no choice but to respond" to his loan requests.

- Despite this, he made no fundamental changes to his own failing business and instead "repeatedly requested" new funds, "utilizing" the lender's vulnerable position.

- He actively "collaborated" in the scheme by helping to facilitate the round-about loan procedures.

Based on this, the lower courts found X guilty as a co-principal in the special breach of trust committed by the B Corp. executives.

The Legal Framework: The Borrower's Dilemma

The defendant's appeal raised a fundamental legal problem. The crime of breach of trust is a crime committed by a fiduciary (like a director) against their own principal (their company). In a loan transaction, the lender and borrower are typically "counter-parties" with opposing interests. The borrower's duty is to their own shareholders, not the lender's. How, then, can a borrower be a co-principal in a crime committed against the lender's company? This seems to defy the ordinary logic of joint criminal enterprise. For a borrower to be a co-principal, the law requires "special circumstances" that elevate them from a mere counter-party to a central actor in the lender's crime.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Forging a "Community of Fate"

The Supreme Court upheld the borrower's conviction as a co-principal. It acknowledged that a borrower would not normally be liable for their lender's breach of trust. However, the Court laid out a multi-factor test to identify the "special circumstances" that can create joint criminal liability.

The Court found that while the defendant did not exercise "dominant influence" or use "socially unacceptable methods" like threats to pressure the lenders, he was still a co-principal because of the combination of the following factors:

- A High Degree of Knowledge: He was fully aware of the lender's breach of duty and the financial damage it was causing to the lending institution.

- Utilization of Vulnerability: He knowingly and strategically "utilized" the fact that the lenders were in a compromised position where they "had no choice but to respond" to his loan requests to save themselves.

- Active Participation: He was not a passive recipient of funds. He "collaborated" in the crime by repeatedly requesting the loans and facilitating the "round-about" financing structure designed to conceal the wrongdoing.

The commentary on this case explains the underlying logic of the Court's decision. In a normal transaction, the parties have opposing interests. But in this case, the years of improper lending and mutual dependency had eroded this relationship. The lender needed to keep lending to hide its past failures, and the borrower needed the loans to survive. Their interests had aligned, and they had become a "community of fate" (unmei kyōdōtai).

In this pathological situation, the borrower is no longer a true counter-party. They are an essential partner in the shared goal of perpetuating a fiction that causes harm to the lender's company. This shared goal and active participation provides the factual basis for finding the borrower to be a co-principal in the crime.

Conclusion: Shared Responsibility in Corporate Crime

The 2003 Supreme Court decision is a vital ruling for understanding corporate criminal liability in Japan. It provides a crucial framework for assessing the responsibility of borrowers in cases involving improper or corrupt lending.

The ruling's core principle is that while lenders and borrowers are typically opposing parties, a codependent "community of fate" can be forged through a cycle of reckless decisions and shared vulnerability. When a borrower has full knowledge of their lender's breach of trust, knowingly exploits the lender's compromised position, and actively collaborates in the illegal transaction, they cross the line from a mere counter-party to a co-principal in the crime. The decision sends a clear and powerful message that in complex corporate crimes, criminal responsibility does not stop on one side of the negotiating table.