The Betrayal of Collateral: A Japanese Ruling on Breach of Trust in Secured Transactions

Imagine a borrower secures a loan from a bank by promising a first mortgage on a valuable piece of real estate. The paperwork is signed, and the bank is ready to register its claim. Before it can, however, the borrower secretly goes to a second lender, takes out another loan, and grants them a first mortgage on the same property, which the second lender immediately registers. The first bank's valuable top-priority claim is now relegated to a riskier second position. Has the borrower merely committed a civil breach of contract, or have they committed the serious white-collar crime of "breach of trust"?

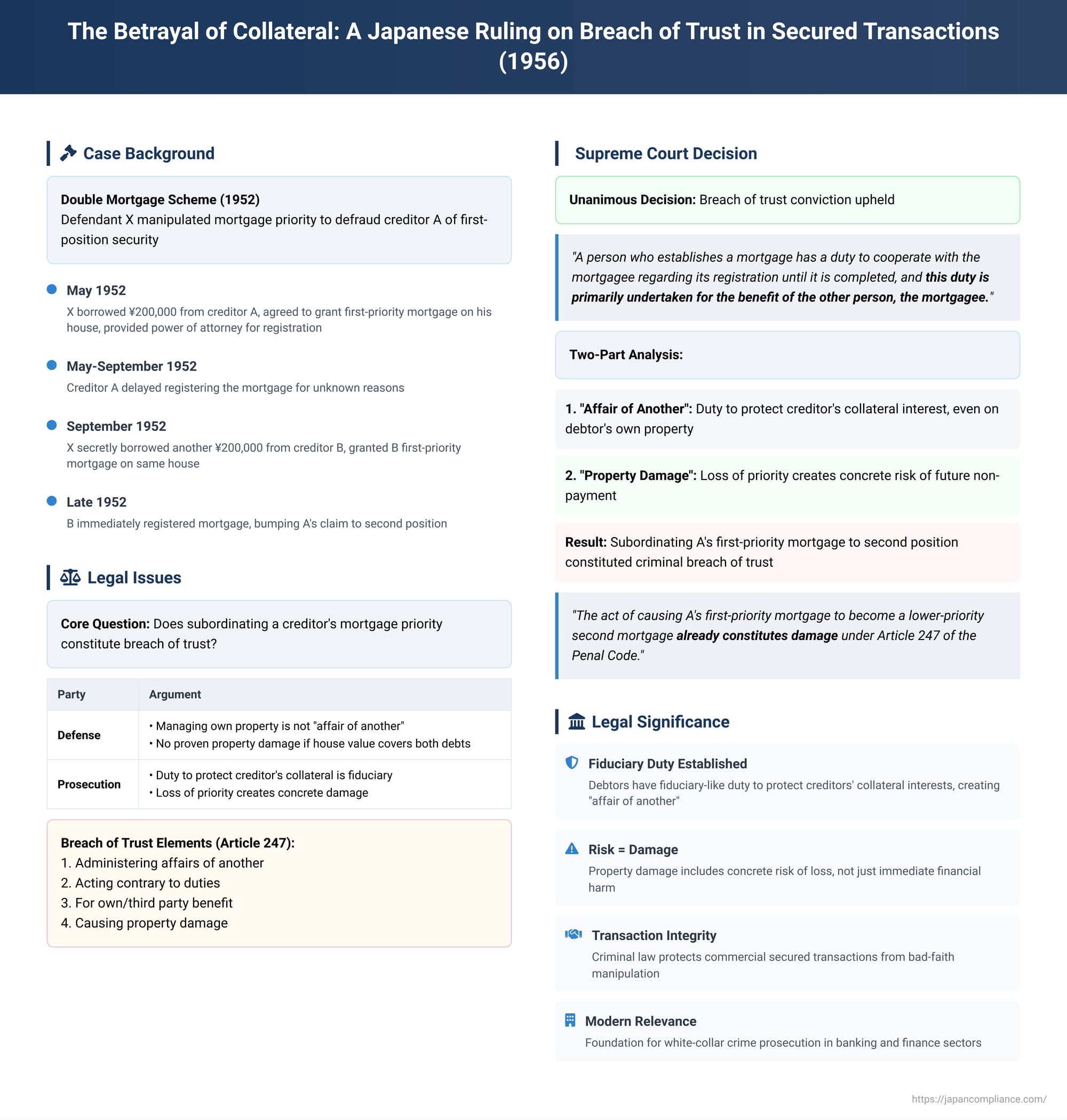

This question, which explores the criminal law's role in protecting the integrity of secured transactions, was the subject of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on December 7, 1956. The Court's ruling established that a debtor's duty to protect a creditor's collateral is an "affair of another," and that diminishing the priority of that collateral is, in itself, a criminal act of breach of trust.

The Legal Framework: The Crime of Breach of Trust (Hainin)

The crime of breach of trust (hainin-zai), defined in Article 247 of the Japanese Penal Code, is a cornerstone of Japanese white-collar criminal law. It is designed to punish disloyalty by those in positions of trust. The key elements of the crime are:

- The perpetrator must be "a person who administers the affairs of another."

- They must act contrary to their duties in that role.

- They must do so for the purpose of benefiting themselves or a third party.

- They must cause "property damage" to the person whose affairs they are administering (the principal).

The 1956 case put the first and fourth elements under intense scrutiny.

The Facts: The Double Mortgage

The case involved a straightforward act of "double-mortgaging." In May 1952, the defendant, X, borrowed 200,000 yen from a creditor, A. To secure the loan, X agreed to grant A a first-priority mortgage on a house he owned. He provided A with all the necessary documents, including a power of attorney, to complete the mortgage registration.

For reasons that are not specified, A did not immediately file the registration documents. Several months later, in September 1952, X, knowing that A's mortgage was still unregistered, went to a second creditor, B, and borrowed another 200,000 yen. To secure this new loan, he granted a first-priority mortgage on the very same house to B. B promptly completed the registration. When A later attempted to register his mortgage, he discovered that his claim was now in second position, subordinate to B's.

The defendant was charged with breach of trust against the first creditor, A. His defense raised two powerful legal arguments:

- His duty to register the mortgage was part of his own contractual obligation—his own affair, not the "affair of another."

- A had not suffered any proven "property damage," because the court had not determined if the value of the house was insufficient to cover both debts. If the house was valuable enough, A would still be paid, and there would be no loss.

The Supreme Court's Ruling, Part 1: The "Affair of Another"

The first and most significant hurdle was whether a debtor, in managing collateral on their own property, could be considered to be "administering the affairs of another." The Supreme Court's answer was a decisive yes.

The Court held:

"It goes without saying that a person who establishes a mortgage has a duty to cooperate with the mortgagee regarding its registration until it is completed, and it must be said that this duty is primarily undertaken for the benefit of the other person, the mortgagee."

This was a pivotal interpretation. The Court reasoned that while the duty arises from the defendant's own contract, its substance is about protecting the property interest of the creditor. Once a creditor has a substantive right to the security, the duty to preserve the value and priority of that collateral is no longer a purely personal affair of the debtor. The debtor, by holding title to the property and being in a unique position to affect the creditor's rights, takes on a fiduciary-like role. In this capacity, they are administering the "affair" of preserving the creditor's asset.

This theory has become foundational in Japanese law. It establishes that the "affair of another" requirement is met when one party has a duty to manage or preserve a specific property interest that has been substantially acquired by another, even if legal title to the underlying asset has not yet formally transferred.

The Supreme Court's Ruling, Part 2: The Meaning of "Property Damage"

The Court then turned to the defendant's second argument: that there was no proof of actual financial loss. The Court rejected this argument just as forcefully, establishing that the risk of loss is sufficient damage for the crime of breach of trust.

The Court stated:

"The priority order of mortgages is a matter concerning the financial interests of which mortgage will be paid in preference from the value of the said mortgaged property. Therefore, the act of causing A's first-priority mortgage to become a lower-priority second mortgage already constitutes damage under Article 247 of the Penal Code."

With this, the Court made it clear that "property damage" in the context of breach of trust does not require a proven, immediate, out-of-pocket loss. The creation of a concrete danger to the value or recovery of an asset is sufficient. The right to be first in line for repayment from collateral is a valuable property interest in itself. Destroying that priority creates a tangible risk of non-payment in the future, especially given that real estate values can fluctuate. This risk is the "damage" the law seeks to punish.

Conclusion: Protecting Trust in Transactions

The Supreme Court's 1956 decision on the double-mortgage scheme is a cornerstone of Japanese white-collar criminal law. It clarifies crucial elements of the crime of breach of trust and extends its protections to the vital commercial area of secured transactions.

The ruling establishes two enduring principles:

- A debtor who grants a security interest in their property, such as a mortgage, takes on a fiduciary-like duty to the creditor to protect the value and priority of that interest. This duty is considered an "affair of another" under the breach of trust statute.

- The act of diminishing a creditor's security, such as subordinating a first-priority mortgage to a second one, constitutes "property damage" in itself, regardless of the current market value of the collateral. The creation of a concrete risk of future loss is sufficient to establish the crime.

This decision serves as a powerful deterrent against bad-faith dealings in lending and finance, affirming that the criminal law protects not just tangible assets, but also the intangible but critically important property interest represented by a creditor's priority status. It underscores the principle that a position of trust, once created, cannot be disloyally abused to another's detriment without facing criminal consequences.