The Banker's Gambit: A Japanese Ruling on Breach of Trust and the Business Judgment Rule

A major corporate client is on the verge of collapse. If they fail, the bank faces catastrophic losses on its existing loans. The bank's top executives, faced with an impossible choice, decide to double down. They approve a series of massive new loans to the failing client, hoping to keep it afloat long enough to engineer a workout and minimize the bank's ultimate losses. Is this a difficult but rational business decision, or is it a criminal breach of trust against the bank and its depositors? When does a bad loan become a crime?

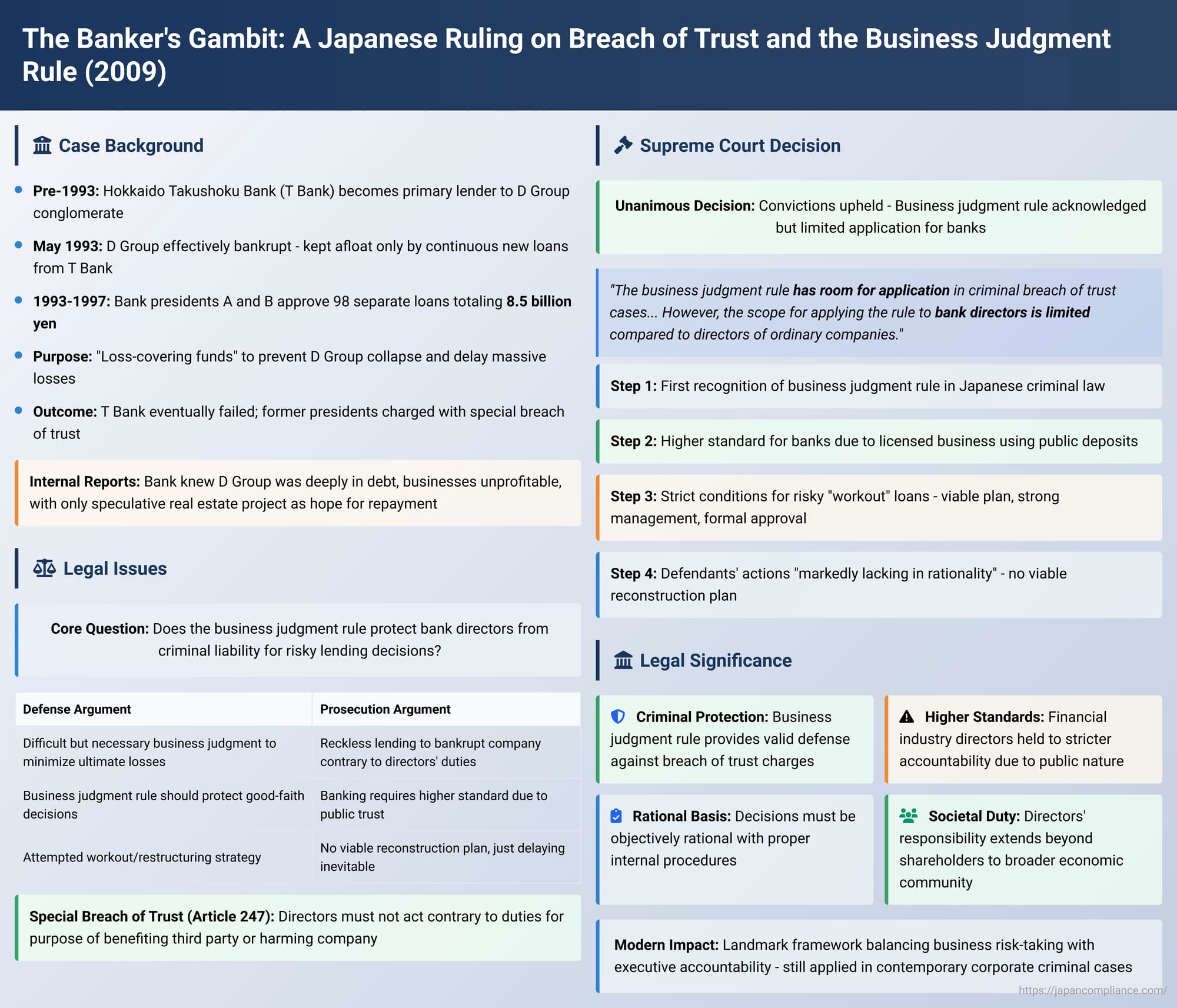

This high-stakes scenario, which tests the very limits of executive responsibility, was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on November 9, 2009. The case, arising from the collapse of the Hokkaido Takushoku Bank (T Bank), one of Japan's most infamous corporate failures, saw the Court grapple with the application of the "business judgment rule" in a criminal context for the first time. The ruling provides a crucial framework for understanding the duties and criminal liability of corporate directors in Japan.

The Facts: The Bank and the Bankrupt Conglomerate

The defendants, A and B, were successive presidents of T Bank. For years, the bank had been the primary lender to a rapidly expanding conglomerate known as the D Group, run by defendant C. While the D Group appeared successful on the surface, its financial situation was dire. By at least May 1993, the group was effectively bankrupt, kept afloat only by a continuous IV drip of new loans from T Bank to cover its massive operating losses.

The bank's own internal reports made the situation clear. The D Group was deeply in debt, its businesses were unprofitable, and its only hope for repayment was a highly speculative and legally fraught real estate project that had little chance of success.

Despite knowing this, defendants A and B, during their respective tenures as president, continued to approve a staggering series of additional loans to the D Group. Over a period of several years, they authorized 98 separate loans totaling over 8.5 billion yen. These loans were essentially unsecured and served primarily as "loss-covering funds" to keep the D Group from collapsing and forcing the bank to realize its massive losses.

When the bank finally failed, the former presidents were charged with special breach of trust. Their defense was that they were not acting disloyally. They argued that their actions were a difficult but necessary business judgment, aimed at minimizing the bank's ultimate losses by preventing an immediate and disorderly bankruptcy of a major client.

The Legal Framework: Breach of Trust and the Business Judgment Rule

The defendants were charged under Japan's special breach of trust statute (tokubetsu hainin-zai), which applies specifically to corporate directors. The crime has several key elements:

- A director must be administering the affairs of the company.

- They must act contrary to their duties.

- They must do so for the purpose of benefiting themselves or a third party, or of harming the company.

- They must cause "property damage" to the company.

The central question was whether the defendants' decision to continue lending to a bankrupt company was an act "contrary to their duties." The defense argued that their actions should be protected by the "business judgment rule" (keiei handan no gensoku). This legal principle, originating in U.S. corporate law, holds that courts should not second-guess the business decisions of corporate directors with the benefit of hindsight. As long as a decision is made in good faith and with due care, directors should not be held liable even if the decision turns out badly.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: A Higher Duty for Bankers

The Supreme Court upheld the convictions, but its reasoning was a masterclass in legal nuance. It provided a definitive framework for how the business judgment rule applies in criminal cases.

Step 1: Acknowledging the Business Judgment Rule

In a landmark statement, the Court declared for the first time that the business judgment rule "has room for application" in criminal breach of trust cases. This was a major victory for the business community, as it provides a potential shield for directors against criminal charges arising from good-faith decisions that fail.

Step 2: A Stricter Standard for Banks

The Court immediately followed this with a crucial qualification. It held that the scope for applying the rule to bank directors is "limited" compared to directors of ordinary companies. The Court gave several reasons for this higher standard: banking is a licensed business that uses the public's deposits as capital; bank directors are expected to be financial experts; and the failure of a bank can cause "widespread and grave confusion for society in general."

Step 3: The Test for Risky "Workout" Loans

The Court acknowledged that there are exceptional circumstances where lending to a failing company might be a rational business decision, such as part of an official workout or restructuring. However, it laid out a strict set of conditions that must be met for such a risky loan to be justified:

- The decision must be based on an "objectively viable reconstruction or workout plan."

- The bank itself must have a "strong management constitution" sufficient to execute such a plan.

- The decision must be made through a formal process, including the creation of a "clear internal plan" and its "formal approval."

Step 4: Application to the Facts

The Supreme Court found that the defendants' actions failed this test completely. The D Group was hopelessly bankrupt with no realistic prospect of recovery. The speculative real estate project was not an "objectively viable reconstruction plan." The defendants had not drafted or followed any "clear internal plan"; they had simply continued to pour money into the failing group to postpone the inevitable.

The Court therefore concluded that their lending decisions were "markedly lacking in rationality" and a clear breach of their fundamental duty as bank directors to protect the bank's assets.

Conclusion: Defining the Boundaries of Executive Responsibility

The 2009 Supreme Court decision in this case is arguably the most important modern ruling on the criminal liability of corporate directors in Japan. It offers a sophisticated framework for balancing the need to allow executives to take business risks against the duty to hold them accountable for disloyalty and recklessness.

The ruling establishes two clear and vital principles:

- The business judgment rule is a valid concept in Japanese criminal law, offering a potential defense for directors against charges of breach of trust.

- However, this protection is not absolute. Directors, especially those in the financial industry, are held to a higher standard of care due to the public nature of their business. A risky decision will only be protected if it is based on an objectively rational plan and proper internal procedures.

The decision serves as a powerful warning to corporate leaders. While the law respects the need for business judgment, it will not protect decisions that are reckless, procedurally improper, or, as the Court found here, "markedly lacking in rationality." It affirms that the duty of a director is not just to their company's shareholders, but also to the broader economic community that relies on their prudent and faithful stewardship.