Asahi Litigation (1967): Supreme Court on Japan’s Constitutional Right to Welfare

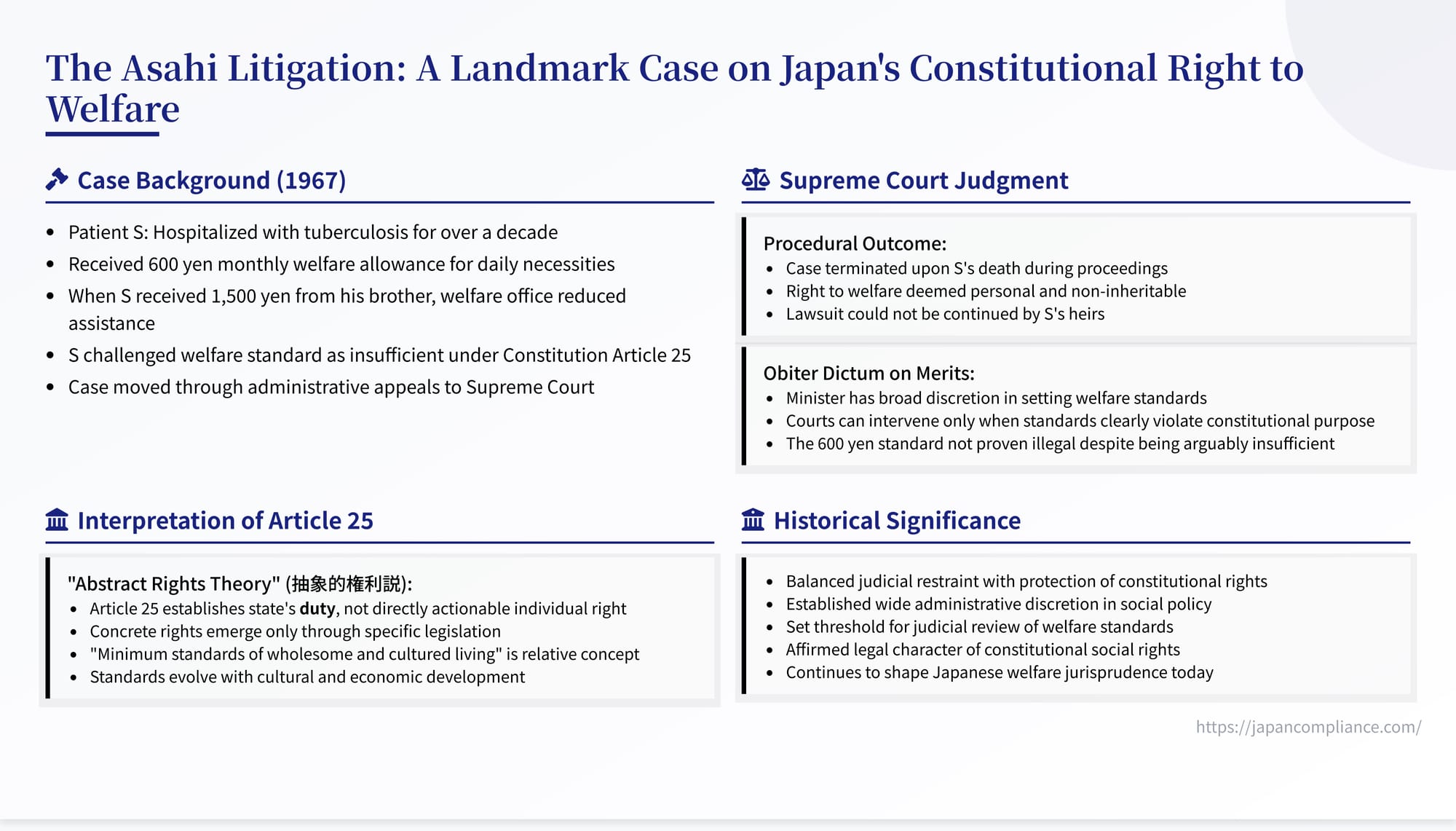

TL;DR: The 1967 Asahi Litigation confirmed that Article 25 provides only an abstract constitutional right, upheld broad ministerial discretion over welfare standards, and ruled such entitlements are strictly personal and non-inheritable.

Table of Contents

- Background of the Case

- The Supreme Court’s Judgment: Procedural Termination

- Dissenting Views on Inheritability

- The Court’s Opinion on the Merits (Obiter Dictum)

- Significance of the Asahi Litigation

The 1967 decision by the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan in the Asahi Litigation (formally, the Case Concerning the Request for Revocation of a Decision on an Appeal Regarding Protection under the Public Assistance Act, Showa 39 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 14) remains a cornerstone in Japanese constitutional law, particularly concerning the interpretation and enforceability of social rights. This case grappled with fundamental questions about the nature of the "right to maintain the minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living" guaranteed by Article 25 of the Constitution, the scope of governmental discretion in setting welfare standards, and the procedural aspects of challenging those standards.

Background of the Case

The appellant, S, had been hospitalized for over a decade at the National Okayama Sanatorium due to tuberculosis. As a single patient requiring long-term care, he received public assistance under Japan's Public Assistance Act (生活保護法, Seikatsu Hogo Hō). This included medical assistance provided in kind (covering treatment and meals) and a monthly livelihood assistance allowance of 600 yen for daily necessities, which was the maximum amount permissible under the standards set by the Minister of Health and Welfare (the appellee, Y) at the time.

Circumstances changed when S began receiving monthly financial support of 1,500 yen from his elder brother, K. Citing the principle of supplementary protection under the Public Assistance Act (which requires exhausting private resources before public aid is granted), the Director of the Tsuyama City Social Welfare Office made a decision in July 1956 to modify S's assistance. The office terminated the 600 yen monthly livelihood assistance. Furthermore, it determined that after deducting the 600 yen (deemed necessary for daily expenses) from the 1,500 yen received from K, the remaining 900 yen should be applied towards S's medical expenses, requiring him to bear a portion of the costs previously covered entirely by medical assistance.

S contested this decision. He first filed an administrative appeal with the Governor of Okayama Prefecture, which was dismissed. He then appealed to the Minister of Health and Welfare (Y), who also rejected the appeal. Consequently, S initiated a lawsuit against Minister Y, seeking the revocation of the Minister's decision to dismiss his appeal.

S's core argument was that the livelihood assistance standard of 600 yen per month was itself illegal. He contended that this amount was insufficient to maintain the "minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living" guaranteed by Article 25 of the Constitution and stipulated as the goal of the Public Assistance Act. He argued the standard failed to meet the actual needs of a hospitalized patient like himself.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Procedural Termination

Before the Supreme Court could fully address the substantive arguments regarding the welfare standard's legality, a crucial procedural event occurred: S passed away on February 14, 1964, while the appeal was pending (the appeal itself was filed on November 20, 1963).

The Court, examining its jurisdiction ex officio, first had to determine whether the lawsuit could be continued by S's heirs, identified as K. Asahi and K. Asahi. The Court's conclusion was definitive: the lawsuit terminated upon S's death and could not be inherited.

The majority opinion reasoned as follows:

- Nature of the Right to Public Assistance: The right to receive public assistance under the Act is not merely a reflection of state benevolence or a side effect of social policy. It is a legal right, which can be termed the "right to receive protection" (保護受給権, hogo jukyūken).

- Personal and Non-Transferable: However, this right is strictly personal (一身専属の権利, isshin senzoku no kenri). It is granted to the specific individual to maintain their own minimum standard of living. As such, it cannot be transferred to others (referencing Article 59 of the Act, which prohibits transferring the right) and cannot be subject to inheritance.

- Right to Claim Arrears: Even the right to claim assistance payments that were already due but unpaid during the recipient's lifetime extinguishes upon death. This applies not only to medical assistance (provided in kind) but also to livelihood assistance (provided in cash). The purpose of these benefits is intrinsically tied to meeting the living recipient's immediate needs for a minimum standard of living; diverting them to other purposes (like inheritance) is impermissible under the Act's intent. Therefore, claims for arrears also cannot be inherited.

- Unjust Enrichment Claims: Any claim for unjust enrichment (不当利得返還請求権, futō ritoku henkan seikyūken) that might arise (e.g., arguing the state was unjustly enriched by applying K's support payment towards medical costs due to an illegally low livelihood standard) is predicated on the existence of the right to receive protection. Since the underlying right is personal and non-inheritable, any dependent unjust enrichment claim is also non-inheritable.

Based on this reasoning, the Court declared the lawsuit concluded upon S's death, with no possibility for his heirs to take over the litigation. The court costs incurred during the intermediate disputes were assigned to the heirs.

Dissenting Views on Inheritability

Several justices disagreed with the majority's conclusion on the procedural issue of inheritability.

Justice Tanaka, in his dissenting opinion, argued that while the right to receive protection itself was personal, the key issue for inheritance in this specific case was different. The lawsuit challenged the decision that effectively required S to use 900 yen of his brother's support for medical costs. If this decision (and the underlying low standard) were deemed illegal and revoked, S (or his estate) would have a claim against the state for unjust enrichment – specifically, for the amount corresponding to the difference between the actual 600 yen standard and a legally appropriate standard, up to the 900 yen applied to medical costs. Justice Tanaka viewed this potential claim for unjust enrichment, essentially a claim for the return of money S should have been free to use, as distinct from the personal right to receive ongoing assistance. He argued such a monetary claim was inheritable. Since exercising this claim required the prior step of revoking the Minister's decision, the heirs had a legitimate legal interest in continuing the revocation lawsuit, aligning with Article 9 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act which recognizes standing even after a decision's effect has lapsed if there's a legal interest to be recovered by revocation. He advocated for interpreting standing requirements broadly to allow judicial review on the merits.

Justices Matsuda and Iwata (joined by Justice Kusaka) also dissented on similar grounds. They emphasized that the potential claim was for unjust enrichment resulting from the state allegedly avoiding its medical aid obligations by imposing an improper co-payment derived from an illegally low livelihood standard. This conditional monetary claim, they argued, was separate from the personal right to assistance and thus inheritable, giving the heirs the necessary legal interest to continue the suit seeking revocation of the Minister's decision.

Despite these dissents, the majority view prevailed, and the case was formally terminated without a ruling on the merits based on S's appeal arguments.

The Court's Opinion on the Merits (Obiter Dictum)

Although the case was concluded procedurally, the Court, recognizing the public importance of the issues raised, provided an extensive "supplementary opinion" (obiter dictum) outlining its views on the substantive questions concerning Article 25 and the legality of the welfare standard. This part of the judgment has become highly influential.

1. Nature of Article 25:

- The Court reaffirmed the stance from a 1948 Grand Bench decision: Article 25, Paragraph 1 ("All people shall have the right to maintain the minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living.") primarily declares the state's duty to conduct national affairs such that all citizens can achieve this standard. It does not directly grant individual citizens a concrete, actionable right against the state.

- Concrete rights to assistance are conferred only through specific legislation enacted to realize the Constitution's purpose, such as the Public Assistance Act.

- Therefore, the right granted by the Act is the right to receive protection in accordance with the standards established by the Minister of Health and Welfare. It is not a right to demand a level of assistance objectively determined to meet a minimum standard independent of the Minister's established criteria.

2. Ministerial Discretion and Judicial Review:

- The Court acknowledged that the "minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living" is an abstract and relative concept. Its specific content evolves with cultural and economic development and depends on numerous uncertain factors.

- Consequently, determining what constitutes this minimum standard is, in the first instance, entrusted to the broad discretion (合目的的な裁量, gōmokutekitekina sairyō) of the Minister of Health and Welfare.

- The Minister's judgment in setting the standard is generally considered a matter of appropriateness or policy (当不当, tōfutō), subject to political accountability, rather than a question of legality (違法, ihō) immediately open to judicial challenge.

- However, this discretion is not unlimited. Judicial review becomes possible if the Minister's determination clearly contravenes the purpose of the Constitution and the Public Assistance Act. This could occur if the Minister sets a standard that is markedly low while disregarding actual living conditions, thereby exceeding the limits of delegated discretion or abusing that discretion (裁量権の限界をこえた場合または裁量権を濫用した場合, sairyōken no genkai o koeta baai mata wa sairyōken o ran'yō shita baai).

- The Court noted the lower court's terminology referring to the standard-setting as "bound discretion" (覊束裁量行為, kisoku sairyō kōi) while still acknowledging the Minister's technical discretion wasn't necessarily contradictory, as even bound acts can involve some level of judgment.

- Crucially, the Court found that considering "extra-livelihood factors" (生活外的要素, seikatsu gaiteki yōso) – such as the overall national income, government finances, general living standards, disparities between urban and rural areas, the living conditions of low-income populations not receiving assistance, public sentiment about relative living standards, and budgetary allocation constraints – falls within the scope of the Minister's discretion when setting the standards. As long as these considerations do not violate the fundamental purpose of the law, they raise questions of policy appropriateness, not legality.

3. Assessment of the 600 Yen Standard:

- The standard in question was established in July 1953, based on the "Market Basket" method (calculating theoretical living costs by pricing a basket of necessary goods and services).

- The Court recognized that the Public Assistance Act requires assistance to be sufficient for a minimum wholesome and cultured standard (Article 3) and tailored to actual needs (Article 9), while also stipulating it must not exceed this minimum level (Article 8, Paragraph 2).

- For hospitalized patients like S, the Court stressed the need to consider the specific constraints of long-term institutionalization and medical treatment objectives.

- While acknowledging that the amount of funds for daily necessities (seikatsu fujo for nichiyōhinhi) can impact treatment outcomes and that insufficiency can have significant negative effects, the Court drew distinctions between different types of assistance. Costs aimed solely at promoting treatment effects, compensating for perceived deficiencies in the medical or nursing systems, or easing post-discharge life could not automatically be categorized as daily necessities covered by the livelihood assistance standard. Such needs might potentially be addressed through medical assistance (iryō fujo, which included meals) or other provisions like vocational assistance (seigyō fujo).

- The Court also stated that the adequacy of the standard for daily necessities should be assessed holistically, considering potential interchangeability between specific budget items and the distinction between regularly recurring needs (covered by the general standard) and temporary or exceptional needs (potentially covered by special standards or one-time payments/loans, the availability and implementation of which were also within ministerial discretion).

- Based on the facts established by the lower court regarding the standard-setting process in 1953 and the circumstances at that time, the Supreme Court concluded that it could not definitively state that the Minister's judgment – deeming 600 yen sufficient for the minimum daily necessities of an inpatient – was illegal due to exceeding or abusing discretionary power.

- The Court did implicitly acknowledge, referencing the lower court's findings and supplementary opinions, that due to rapid economic growth between 1953 and 1956 (the time of the challenged decision), the 600 yen standard might have become insufficient to fully meet the minimum needs by then. However, it suggested that some lag between changing economic conditions and the revision of standards is inevitable given the complexities of research and calculation involved. Unless the discrepancy becomes so significant as to fundamentally undermine the purpose of the Constitution and the Act, such a delay within a reasonable period for revision might be legally tolerated.

4. Concurring/Dissenting Views on the Merits:

- Justice Okuno, in a supplementary opinion, while agreeing with the procedural termination, expressed disagreement with the majority's obiter view on the nature of the right. He argued that Article 25 does envision an objective minimum standard, not merely one determined by the Minister. Therefore, the Minister's standard-setting is an act of law enforcement aimed at realizing this objective standard, and an erroneous judgment would constitute illegality subject to judicial review. However, he conceded that a standard, once properly set, doesn't become instantly illegal just because subsequent economic changes create a minor gap, provided the gap isn't egregious and occurs within a reasonable timeframe for revision. On the facts, he reluctantly concurred with the lower court's finding that the 600 yen standard, while perhaps low, wasn't demonstrably illegal in 1956.

- Justice Tanaka, after arguing for inheritability, addressed the merits. He largely agreed with the majority's (and Justice Okuno's) interpretation of Article 25 as establishing an abstract right realized through legislation, and the Minister's broad discretion limited by potential abuse. He acknowledged the 600 yen was likely too low by 1956 but agreed that the standard-setting process itself wasn't irrational (using the Market Basket method) and that considering "extra-livelihood factors" was permissible. He also drew the same distinctions between livelihood and medical assistance (e.g., regarding supplementary food costs). Ultimately, he concluded that while the standard was regrettably low and should have been addressed politically, the deficiency wasn't severe enough to be deemed unconstitutional or illegal from a judicial standpoint at the time of the challenge, considering the inherent delays in standard revision. He ended with a strong call for the government to reflect on the case and ensure more timely and appropriate welfare administration.

Significance of the Asahi Litigation

The Asahi decision, despite terminating the specific lawsuit, profoundly shaped the understanding of social rights under the Japanese Constitution.

- "Abstract Rights Theory": It established what is often called the "Abstract Rights Theory" (抽象的権利説, chūshōteki kenrisetsu) regarding Article 25. While not granting directly enforceable concrete claims, the provision is more than mere political guidance; it has legal normative force, obligating the legislature and administration to act and setting legal boundaries. Concrete rights emerge through legislation like the Public Assistance Act.

- Ministerial Discretion and Judicial Restraint: The ruling confirmed the wide discretion granted to administrative bodies (specifically the Minister of Health and Welfare) in formulating social policy and setting standards, particularly where complex socio-economic factors are involved. Courts should generally defer to this discretion.

- Limits on Discretion: Simultaneously, it crucially opened the door for judicial review in cases where administrative discretion is clearly abused or deviates fundamentally from constitutional and statutory mandates. This established a threshold (albeit a high one) for challenging the legality of welfare standards.

- Personal Nature of Welfare Rights: The holding on the non-inheritability of the right to receive protection underscored the personal, need-based nature of welfare benefits under the Japanese system.

The Asahi Litigation thus struck a balance: upholding the principle of judicial restraint in complex social policy matters while affirming the legal character of constitutional social rights and retaining a role for courts in policing the boundaries of administrative power. Its legacy continues to inform debates about the scope of social rights, governmental obligations, and the role of the judiciary in welfare issues in Japan.

- Sustainable Pensions vs. Recipient Rights: Japan’s Supreme Court Addresses Pension Cuts (2023)

- The Horiki Litigation: Legislative Discretion and Social Security Benefits in Japan (1982)

- Defining the Boundaries: Public Assistance and Undocumented Foreign Residents in Japan (2001)

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare — Outline of the Public Assistance System

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/care-welfare/social-welfare/index.html