The Art of the Dine-and-Dash: A Japanese Ruling on the Anatomy of Fraud

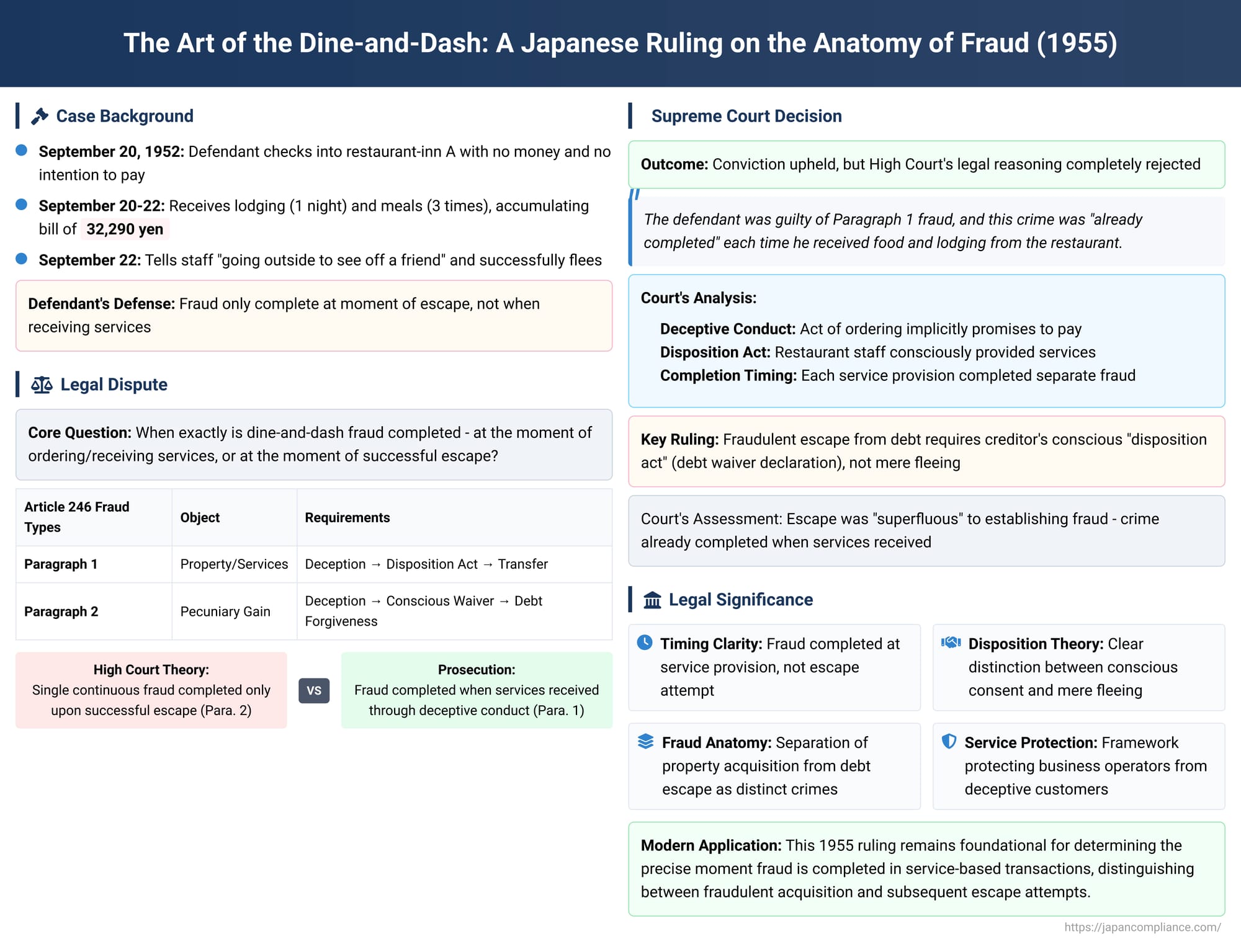

A person walks into a fine restaurant with no money and no intention of paying. They enjoy a lavish meal over several days, running up a large bill. When the time comes to settle the account, they tell the staff they are just stepping outside to see a friend off, and then they disappear into the night. We call this a "dine-and-dash," and it feels like a classic case of fraud. But legally, when exactly was the crime committed? Was it when the food was ordered? When it was consumed? Or only at the moment of the final, successful escape?

This fundamental question, which dissects the anatomy of the crime of fraud, was the subject of a foundational ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan on July 7, 1955. The Court's decision clarified the precise moment a "dine-and-dash" becomes a completed crime, distinguishing between the fraud of obtaining services and the separate (and more difficult to prove) fraud of escaping a debt.

The Facts: The Restaurant Stay and the Getaway Lie

The defendant, with no money and no intention to pay, checked into a restaurant-inn, identified as "restaurant A," on September 20, 1952. Over the next two days, he received one night's lodging and three meals, accumulating a bill of 32,290 yen. On September 22, he put his escape plan into action. He told the staff he was going outside to see off a friend who was leaving by car. Once at the front of the restaurant, he fled.

The defendant was charged with and convicted of fraud under Article 246 of the Penal Code. The lower courts, particularly the High Court, reasoned that the defendant's entire course of conduct—from the initial order to the final escape—should be viewed as a single, continuous criminal act. The High Court held that the crime of fraud was only truly completed at the moment of the successful escape, when the defendant had deceived the staff and managed to evade payment of the bill.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Correction: Two Types of Fraud, One Crime Committed

The defendant appealed, and while the Supreme Court upheld his conviction, it did so by completely rejecting the lower court's legal reasoning. The Court used the case to draw a sharp and crucial distinction between the two different types of fraud defined in Article 246 of the Penal Code.

- Paragraph 1 Fraud: Defrauding a person to obtain property or services.

- Paragraph 2 Fraud: Defrauding a person to obtain a pecuniary gain, such as the cancellation of a debt.

The High Court had incorrectly conflated these, treating the defendant's act as a Paragraph 2 fraud for "escaping payment" that was completed upon his escape.

Clarification 1: Fraudulently Escaping a Debt Requires a "Disposition Act."

The Supreme Court first clarified the law for Paragraph 2 fraud. It ruled that to be guilty of fraudulently escaping a debt, it is "not enough to simply flee and factually not pay". The perpetrator must deceive the creditor into performing a conscious "disposition act" (shobun kōi), such as making a "declaration of waiver of the debt" (saimu menjo no ishi hyōji). Because the restaurant owner never made such a declaration, the defendant's act of fleeing did not constitute a completed Paragraph 2 fraud. The High Court's reasoning was, in the Supreme Court's words, "improper" (shittō).

Clarification 2: The Fraud Was Already Complete When the Services Were Received.

The Supreme Court then explained when the actual crime had been committed. It ruled that the defendant was guilty of Paragraph 1 fraud, and that this crime was "already completed" each time he received food and lodging from the restaurant.

- The "Deceptive Act": The deception was not an explicit verbal lie, but a "deception by conduct" (suidan-teki gimō). The very act of ordering food or booking a room at a commercial establishment is an implicit representation—a promise—that one intends to pay. By ordering with no intention to pay, the defendant's conduct was fraudulent from the very beginning.

- The "Property" Obtained: The property the defendant fraudulently obtained was the food, beverages, and the service of lodging.

- The Moment of Completion: Each time the restaurant staff, deceived by the defendant's conduct, provided him with these goods and services, a separate act of fraud was completed.

The Court concluded that the lower court's mention of the final escape was legally "superfluous" (muyō) to establishing the crime, because the crime of fraud had already been completed long before the defendant fled.

Analysis: The "Disposition Act" and the Line Between Theft and Fraud

The Supreme Court's emphasis on the "disposition act" is fundamental to the structure of Japanese property crime law. It is the key element that distinguishes fraud from theft. In theft, a perpetrator takes property against the victim's will. In fraud, the victim is tricked into consenting to the transfer of their property. This act of consent, however flawed, is the "disposition act."

What constitutes a disposition act is a matter of intense legal debate. The most extreme theories are:

- "Disposition Intent Required": This theory requires a fully conscious, intentional act of disposition by the victim.

- "Disposition Intent Not Required": This theory argues any external transfer of property is sufficient. The commentary on this case criticizes this view for blurring the line with theft. It offers the example of an unmanned roadside vegetable stand with a sign that says, "Please put money in the box." A person who takes vegetables without paying is guilty of theft, not fraud, because the vendor has not performed a "disposition act" by simply putting the vegetables on display; they have merely created an opportunity for a legitimate transaction or a theft.

The prevailing view in Japan is an intermediate one: the "Relaxed Disposition Intent" theory. This view does not require that the victim fully understand all aspects of the transaction, but it does require that they consciously perform an act that they know will transfer control of the property to the perpetrator.

In the "dine-and-dash" scenario, the restaurant owner consciously provides the food and lodging, fulfilling the requirement for a disposition act for Paragraph 1 fraud. However, as the Supreme Court ruled, when the patron flees, the owner performs no conscious act to waive the debt, so there is no disposition act for Paragraph 2 fraud.

Conclusion: Pinpointing the Precise Moment of the Crime

The 1955 Supreme Court decision provides a clear and enduring anatomy of the crime of fraud in the classic "dine-and-dash" scenario. Its legacy is twofold:

- It clarifies that the crime of fraud for obtaining goods or services is completed at the moment the victim provides them, based on the perpetrator's deceptive conduct (such as the implicit promise to pay when ordering).

- It establishes that fraudulently escaping a debt requires more than just running away; it requires deceiving the creditor into making a conscious disposition, such as a declaration that the debt is forgiven.

This ruling offers a precise, logical framework that correctly identifies the moment the victim's property rights are violated. It ensures that the crime is properly defined by the fraudulent acquisition of goods and services, rather than being conflated with the perpetrator's subsequent actions to escape the consequences.