The Anonymous Crowd as a Single Victim: How Japan's Supreme Court Redefined Fraud

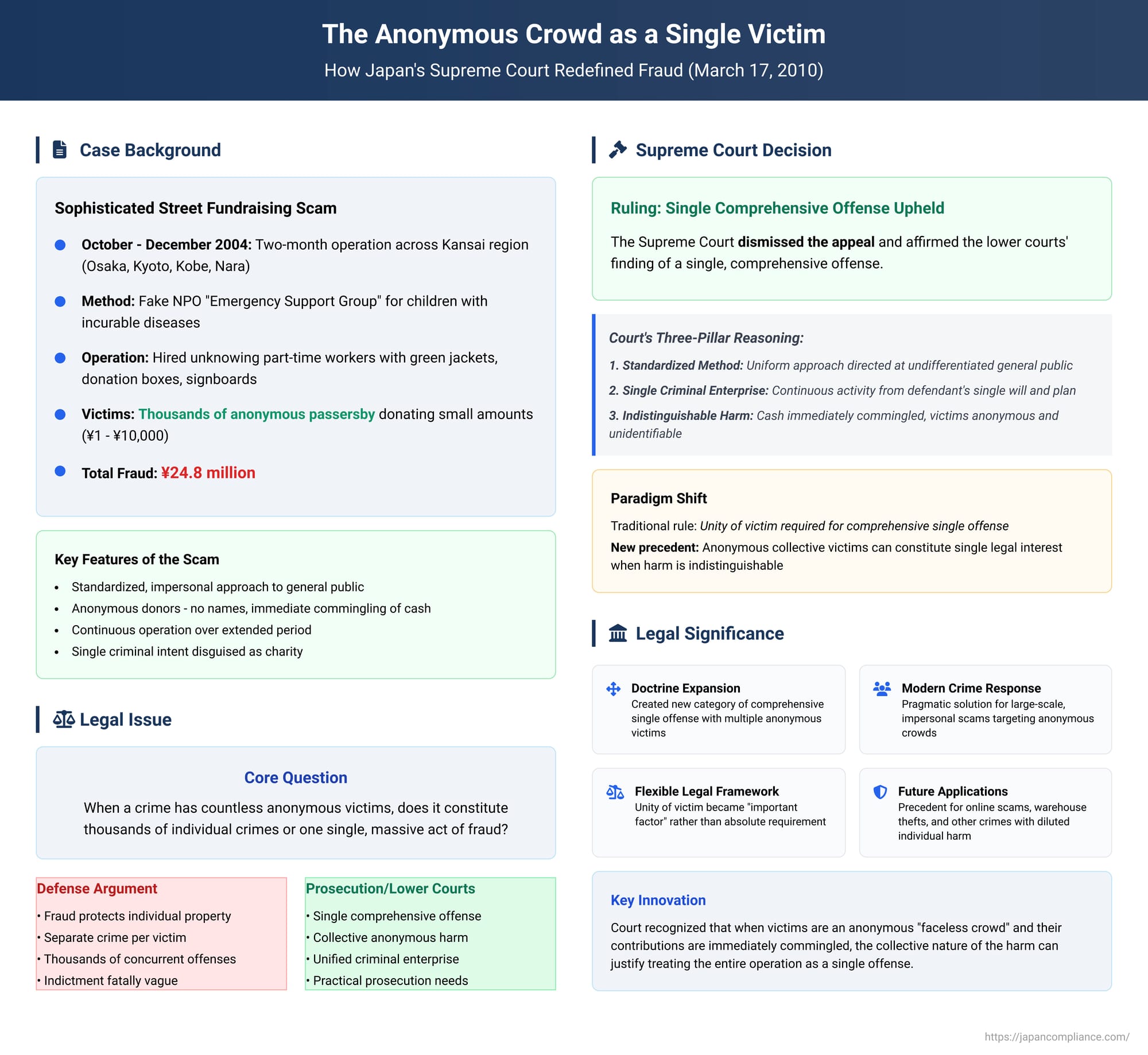

On March 17, 2010, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark decision that fundamentally reshaped the understanding of fraud in the modern era. The case involved a large-scale street fundraising scam where thousands of anonymous passersby were duped into donating small amounts of money. This raised a critical legal question: when a crime has countless, unidentifiable victims, does it constitute thousands of individual crimes, or can it be treated as one single, massive act of fraud?

In a groundbreaking ruling, the Court concluded that the entire two-month operation was a "comprehensive single offense" (hōkatsu-ichizai). This decision marked a significant departure from traditional legal principles, which had long held that a separate crime is committed against each individual victim. By recognizing the collective and anonymous nature of the harm, the Court created a new precedent for prosecuting complex, large-scale frauds targeting the public at large.

The Anatomy of a Sophisticated Scam

The case centered on a defendant who orchestrated a fraudulent fundraising operation under the guise of a noble cause. The scheme was elaborate and well-organized:

- The Pretense: The defendant planned to defraud the public by pretending to collect money for a non-profit organization (NPO) that supported children with incurable diseases.

- The Operation: For approximately two months, from late October to late December 2004, the operation was active on the streets of major cities in the Kansai region, including Osaka, Kyoto, Kobe, and Nara.

- The Method: The defendant hired numerous part-time workers who were unaware of the scam's true nature. These workers were deployed to busy public areas, equipped with green jackets, donation boxes, and large signboards bearing slogans like "Let's Save Young Lives!" and the name of a fictitious NPO, the "Emergency Support Group." They were instructed to shout appeals for donations, such as, "Please help us save children with incurable diseases."

- The Deception: The defendant's real intention, which was concealed from both the workers and the public, was to use the vast majority of the collected funds for his own personal expenses after deducting costs and personnel fees.

- The Result: Believing their money would go to sick children, a multitude of anonymous passersby donated cash in amounts ranging from a single yen coin to a 10,000 yen bill. The total amount defrauded was approximately 24.8 million yen.

Both the trial court and the first appellate court found that this entire series of acts constituted a single, comprehensive offense of fraud.

The Defense's Challenge: A Crime Against Individuals

The defense appealed to the Supreme Court, mounting a challenge based on the foundational principles of criminal law. Their argument was twofold:

- Fraud is a Crime Against Individual Property: The defense argued that the crime of fraud protects the property of individuals. Therefore, a legally distinct crime is committed against each person who is deceived into donating money.

- The Offenses Should Be Concurrent: Consequently, the defendant's actions should not be treated as a single offense, but as thousands of separate crimes that are "concurrent" (heigō-zai).

This line of reasoning was not merely theoretical. If successful, it would have had profound procedural implications. If the case involved thousands of separate crimes, the indictment would need to specify the details of each one—the victim, the date, the time, the place, and the amount. Since the prosecution could not possibly identify the vast majority of the anonymous donors, the defense argued that the indictment was fatally vague and should be dismissed. This position was supported by prior high court precedents which had held that in fraud cases with multiple victims, each act of deception constitutes a separate offense.

The Supreme Court's Decision: A Single Fraud Against the Collective

The Supreme Court rejected the defense's appeal, affirming the lower courts' finding of a single, comprehensive offense. The Court acknowledged that the precedents cited by the defense were different in nature and laid out a novel legal logic tailored to the unique characteristics of this street fundraising scam.

The Court’s reasoning rested on three key pillars:

- A Standardized, Impersonal Method: The Court noted that this was not a scheme that targeted victims individually. Instead, it was an operation that deployed a "standardized and uniform approach" directed at the general, undifferentiated public. The same deceptive message was broadcast continuously, day after day, in various locations.

- A Single, Continuous Criminal Enterprise: The entire two-month campaign was recognized as a continuous activity stemming from the "defendant's single will and plan." It was not a series of independent decisions to commit fraud but one overarching criminal venture.

- The Indistinguishable Nature of the Harm and Victims: This was the most innovative part of the ruling. The Court highlighted the inherent nature of anonymous street fundraising. Donors typically drop small amounts of cash into a donation box and walk away without giving their names. The moment the money enters the box, it "is immediately commingled with the cash contributed by other victims and loses its identifiability." The defendant did not receive the money from each victim separately; it was collected as an undifferentiated mass.

Considering these unique features, the Court concluded that it was appropriate to "evaluate the entire operation as a single entity and interpret it as a comprehensive single offense." As a result, the indictment was deemed sufficiently specific by identifying the victims as "the numerous persons who responded to the fundraising," and by stating the method, period, locations, and total amount of the fraud.

Analysis and Legal Significance: A Paradigm Shift

This 2010 decision is widely regarded as a watershed moment in Japanese criminal law, as it boldly carved out a new exception to a long-standing rule.

A Departure from Traditional Doctrine

Traditionally, the doctrine of a "comprehensive single offense" was applied to a series of criminal acts under strict conditions. One of the most crucial prerequisites was the "unity of the protected legal interest"—meaning, fundamentally, that there was a single victim. This principle held that if different victims were harmed, their legal interests were distinct, and thus a separate crime was committed against each.

Previous Supreme Court rulings that had recognized a comprehensive single offense in cases of repeated acts did so only when the victim was the same person. Examples include a doctor repeatedly administering illegal drugs to the same patient, or a person subjecting the same victim to a continuous series of assaults in a domestic violence context. In cases of fraud with multiple victims, the established view in both case law and academic theory was that separate crimes were committed and should be treated as concurrent offenses. This decision directly challenged and overcame that barrier.

The Creation of a New Category of "Single Offense"

The Supreme Court effectively created a new category of comprehensive single offense—one that can exist even with a multitude of victims. The Court achieved this by shifting the analytical focus. Instead of making the unity of the victim an absolute requirement, it treated it as one factor among many, and found that other elements could be strong enough to justify a single-offense classification. The key justifications were the structural features of the crime itself: the impersonal method, the singular intent, and, most importantly, the anonymous and collective nature of the victims and their financial contributions.

This conclusion has been widely supported by legal scholars, who have pointed to several underlying rationales:

- Anonymity and Lack of Individuality: The victims in this case were an anonymous, "faceless" crowd. The individual character of their legal interest was seen as extremely diluted.

- Triviality of Individual Harm: While the total amount was large, the loss for each individual donor was relatively small, further diminishing the legal significance of each separate act.

- A Pragmatic Response to Modern Crime: To insist on identifying each victim would make prosecuting such large-scale, impersonal scams practically impossible, creating an unacceptable gap in the law.

Conversely, some critics have argued that this decision stretches the definition of fraud too far, effectively creating a new crime of "collective fraud risk" that is not specified in the Penal Code, potentially violating the principle of legality (nulla poena sine lege).

The Insight from the Supplemental Opinions

The depth of the Court's reasoning is further revealed in the supplemental opinions issued by two of the justices. One justice, in particular, offered a crucial theoretical key: that the "unity of the protected legal interest" should not be considered an absolute "requirement" for a comprehensive single offense, but rather an "important factor" in the overall evaluation. This flexible approach allows courts to look at the totality of the circumstances. In a case like this, where the criminal method is unique and the victims are inherently anonymous and their harm commingled, the lack of a single victim can be outweighed by other unifying factors.

Future Implications

The ruling in the street fundraising scam case serves as a vital precedent for other types of property crimes where the individuality of the victims or the stolen property is weak or non-existent. It could be applied to cases like the theft of goods belonging to multiple owners from a single warehouse, or complex online scams that defraud thousands of users of small amounts of money.

A more distant but significant debate is whether this logic could ever extend beyond property crimes to offenses against strictly personal legal interests, such as defamation. For now, the decision stands as a powerful example of judicial adaptation, ensuring that the law remains effective against evolving forms of criminal enterprise that seek to exploit the anonymity of the crowd.