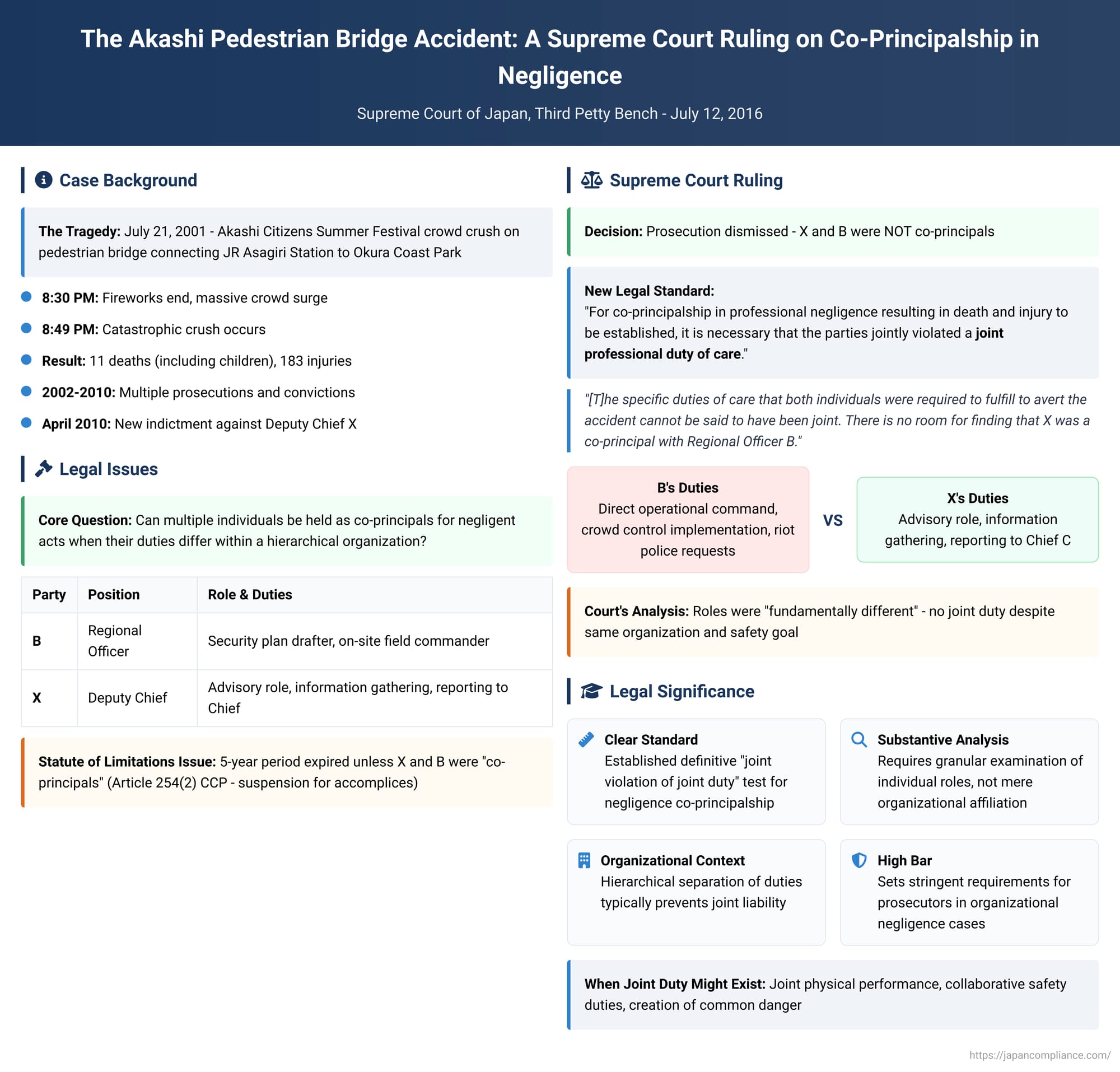

The Akashi Pedestrian Bridge Accident: A Supreme Court Ruling on Co-Principalship in Negligence

Decision of the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan, July 12, 2016

(Case No. 2014 (A) No. 747: Case of Professional Negligence Resulting in Death and Injury)

Introduction

On July 12, 2016, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant decision concerning the legal concept of "co-principalship in negligence." The case stemmed from the tragic Akashi pedestrian bridge accident in 2001, a crowd crush disaster that resulted in numerous deaths and injuries. This ruling addressed a critical question at the intersection of criminal law and organizational responsibility: when can multiple individuals within a hierarchical organization be held jointly responsible as co-principals for a negligent act? The Court’s decision clarified the requirements for establishing co-principalship in negligence, particularly in the context of a statute of limitations defense, providing a definitive standard for a long-debated area of Japanese criminal law.

Factual Background

The Disaster

The incident occurred on the evening of July 21, 2001, in Akashi City, Hyogo Prefecture. A massive crowd had gathered for the 32nd annual Akashi Citizen Summer Festival, which featured a fireworks display. A pedestrian bridge, connecting the nearest Japan Railways station (Asagiri Station) to the event site at Okura Coast Park, became a fatal bottleneck. As the fireworks ended around 8:30 PM, a surge of people leaving the park collided with another group of attendees heading from the station towards the park. The immense crowd pressure on the bridge led to a catastrophic crush. By approximately 8:49 PM, people had fallen and were trampled, resulting in the deaths of 11 individuals, including several children, and injuring 183 others. The cause of death for most victims was compressive asphyxia.

Initial Prosecutions and the Statute of Limitations

In the aftermath, several individuals were prosecuted for professional negligence resulting in death and injury. These included officials from the Akashi City government, a senior manager from a private security company, and a police officer, B, who served as a regional officer for the Akashi Police Station. Their convictions were finalized, treating each as a sole principal whose independent negligence contributed to the disaster—a concept known as "concurrent negligence."

Years later, a new indictment was brought against another individual: X, who was the Deputy Chief of the Akashi Police Station at the time of the accident. This prosecution, initiated on April 20, 2010, was based on a resolution by the Committee for the Inquest of Prosecution, a citizen panel that can compel prosecution even if public prosecutors decline to press charges.

However, this new case faced a significant hurdle: the statute of limitations. For the crime of professional negligence resulting in death and injury, the statute of limitations is five years. The clock started running from the date the final injury occurred, meaning the period would have expired long before X was indicted in 2010.

To overcome this, the court-appointed attorneys acting as prosecutors invoked Article 254, Paragraph 2 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. This provision states that the statute of limitations is suspended for an accomplice (kyōhan, a term encompassing co-principals and other parties to a crime) when a public prosecution is instituted against another accomplice in the same case. The prosecutors argued that X and B, the previously convicted regional officer, were co-principals in the negligent act. Therefore, the prosecution of B in 2002 had suspended the statute of limitations for X. The entire case hinged on whether X and B could legally be considered "co-principals in negligence."

The Core Legal Issue: Defining Co-Principalship in Negligence

In Japanese criminal law, co-principalship, as defined in Article 60 of the Penal Code, applies to "two or more persons who act jointly in the commission of a crime." For intentional crimes, this "joint action" is typically established through evidence of a common criminal intent or conspiracy, followed by a division of labor in executing the crime.

The concept becomes far more complex when applied to crimes of negligence. Negligent offenses, by their nature, lack criminal intent. Individuals do not conspire to be careless. Instead, liability arises from a failure to exercise a legally required "duty of care" to prevent a foreseeable harm. For decades, Japanese legal scholars and courts debated whether and how the doctrine of co-principalship could apply to such offenses.

In this case, the prosecutors advanced the theory that X and B were co-principals. They argued that both men shared a common duty to prevent the crowd disaster and that their collective failures—both in the planning stages and on the day of the event—constituted a joint commission of the crime. The indictment specifically pointed to two phases of negligence:

- The Planning Phase: Failing to formulate an adequate security plan prior to the festival.

- The Incident Response Phase: Failing to implement proper crowd control measures, such as restricting access to the bridge, as the hazardous situation unfolded on the day of the festival.

The Rulings of the Lower Courts

The case was first heard at the Kobe District Court. The court found that X did not have the requisite foreseeability of the tragic outcome and, consequently, did not breach a specific duty of care. It therefore denied the existence of co-principalship and dismissed the prosecution against X, ruling that the statute of limitations had expired.

The prosecutors appealed to the Osaka High Court. While the High Court partially disagreed with the District Court's assessment of foreseeability, it ultimately reached the same conclusion. It found no evidence of a breach of a duty of care attributable to X that would make him a co-principal with B. It upheld the dismissal. The prosecutors then made a final appeal to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court, in its decision on July 12, 2016, addressed the matter ex officio (by its own authority), setting aside the technical grounds of the appeal to rule on the core substantive issue: the requirements for co-principalship in negligence.

The Establishment of a New Legal Standard

First, the Court acknowledged that co-principalship in negligence can, in principle, exist. This in itself was a significant affirmation. It then proceeded to establish a clear and definitive test for its application. The Court held:

"For co-principalship in a crime of professional negligence resulting in death and injury to be established, it is necessary that the parties jointly violated a joint professional duty of care."

This "joint violation of a joint duty" formula became the central pillar of the Court's analysis. The question was no longer simply whether multiple people were negligent, but whether their duties were so intertwined as to be considered "joint" and whether their violations of those duties were also "joint."

Analysis of the Roles and Duties of X and B

The Supreme Court meticulously analyzed the official roles and actual conduct of X (the Deputy Chief) and B (the Regional Officer) within the Akashi Police Station's command structure.

The Command Structure:

- C, the Chief of Police: Held ultimate authority and final decision-making power over the security plan for the summer festival. On the day of the accident, he was the Commander of the on-site police headquarters, overseeing all aspects of security.

- B, the Regional Officer: Was the head of the department responsible for crowd control. He was appointed by Chief C as the primary person in charge of drafting the security plan. On the day of the event, he was the field commander at the local security headquarters set up near the bridge. He had the authority to command officers on the ground and could directly request the deployment of riot police, either through Chief C or on his own initiative in an emergency.

- X, the Deputy Chief: His role was to assist Chief C in managing the overall affairs of the police station. For the security plan, his involvement was based on instructions from Chief C, consisting of providing advice to officers working under B and attending meetings. On the day of the event, he was the Deputy Commander at the main police headquarters (located at the station, not on-site). His duty was to gather information, report to Chief C, and offer recommendations, thereby assisting the Chief in exercising his command authority properly.

Divergent Duties of Care:

Based on this factual record, the Supreme Court found that the roles of B and X were "fundamentally different." This fundamental difference led to a divergence in their specific duties of care to prevent the accident.

- B's Duties: As the primary planner and on-site commander, B's duty of care was direct and operational. In the planning phase, it was to properly create the security plan. On the day of the accident, as the situation deteriorated around 8:00 PM, his duty was to command his subordinate officers to implement crowd control measures, such as restricting entry to the bridge, and to request the deployment of riot police.

- X's Duties: As the Deputy Chief assisting the Chief, X's duty of care was auxiliary and advisory. Throughout both the planning and response phases, his primary obligation was to provide advice and recommendations to Chief C, ensuring that the Chief's supervision of B and other officers was exercised appropriately. He gathered information from the station and reported it, but his ability to perceive the on-site situation was limited to radio communications and a single CCTV monitor.

Conclusion: No "Joint Duty," No Co-Principalship

Because their roles and responsibilities were fundamentally different, the Court concluded that their specific duties of care could not be considered "joint."

"[T]he specific duties of care that both individuals were required to fulfill to avert the accident cannot be said to have been joint. There is no room for finding that X was a co-principal with Regional Officer B in the crime of professional negligence resulting in death and injury."

The Court reasoned that while both men worked for the same organization and towards the same general goal of public safety, their obligations were distinct. B had a duty of direct action and command. X had a duty of counsel and support to a higher authority. A joint duty could not be forged from these separate responsibilities.

Consequently, X and B were not co-principals. The prosecution of B did not suspend the statute of limitations for X. Because the five-year period had expired by the time X was indicted, the Supreme Court affirmed the lower courts' dismissal of the prosecution.

Analysis and Implications

The Supreme Court's 2016 decision has had a profound impact on Japanese criminal law, particularly in cases of organizational negligence.

A Clear Standard for a Vexing Problem

The ruling’s primary significance lies in its clear articulation of the "joint violation of a joint duty" standard. For decades, the application of co-principalship to negligence was ambiguous. This decision provided a concrete and stringent test, moving away from vague notions of "common carelessness" and demanding a specific, shared obligation as a prerequisite for joint liability.

Emphasis on Substantive Roles over Formal Association

The decision underscores that mere affiliation with the same organization or project is insufficient to establish a joint duty. The courts must conduct a granular analysis of each individual's concrete roles, authority, and specific obligations within the organizational structure. In a hierarchy, a subordinate with direct operational duties (like B) and a superior with advisory or support duties (like X) are unlikely to share a "joint" duty, even if they are both working to prevent the same harm.

When Might a "Joint Duty" Exist?

While the Court denied a joint duty in this case, its reasoning helps illuminate when one might be found. Drawing from the logic of this decision and prior lower court cases, co-principalship in negligence would more likely be affirmed in situations such as:

- Joint Performance of a Physical Act: Two individuals jointly and physically perform a dangerous act, such as two unqualified persons collaborating to operate a ship that runs aground.

- Creation and Abandonment of a Common Danger: Two workers each use a blowtorch and both leave their torches unextinguished, collectively creating a fire hazard that leads to a fire.

- Collaborative and Indivisible Safety Duties: Two railway crossing guards whose duties require them to actively coordinate to monitor an approaching train and warn traffic, and their failure to collaborate leads to a fatal accident.

In contrast, where duties are performed independently or are hierarchically separated (e.g., a subordinate's failure to act and a supervisor's failure to oversee), establishing a "joint" duty becomes significantly more difficult.

The Lens of Organizational Negligence

This case is a classic example of "organizational negligence." The Akashi police department as a whole clearly failed in its duty to ensure public safety. However, criminal liability is personal. The challenge is to attribute that organizational failure to specific individuals. This ruling demonstrates a cautious approach, refusing to assign joint criminal responsibility without a clear and specific basis. It insists on a rigorous examination of individual roles before two or more people can be bound together as co-principals in a crime they did not intend to commit.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision in the Akashi pedestrian bridge accident case marked the end of a long legal battle over accountability for a national tragedy. Legally, it stands as a landmark ruling that brought much-needed clarity to the concept of co-principalship in negligence. By establishing the "joint violation of a joint duty" test, the Court created a high bar for prosecutors seeking to hold multiple parties jointly liable for a negligent outcome. The judgment serves as a powerful reminder that in matters of organizational responsibility, criminal liability must be tethered to the specific, concrete duties of each individual actor, not just their shared proximity to a disastrous event.