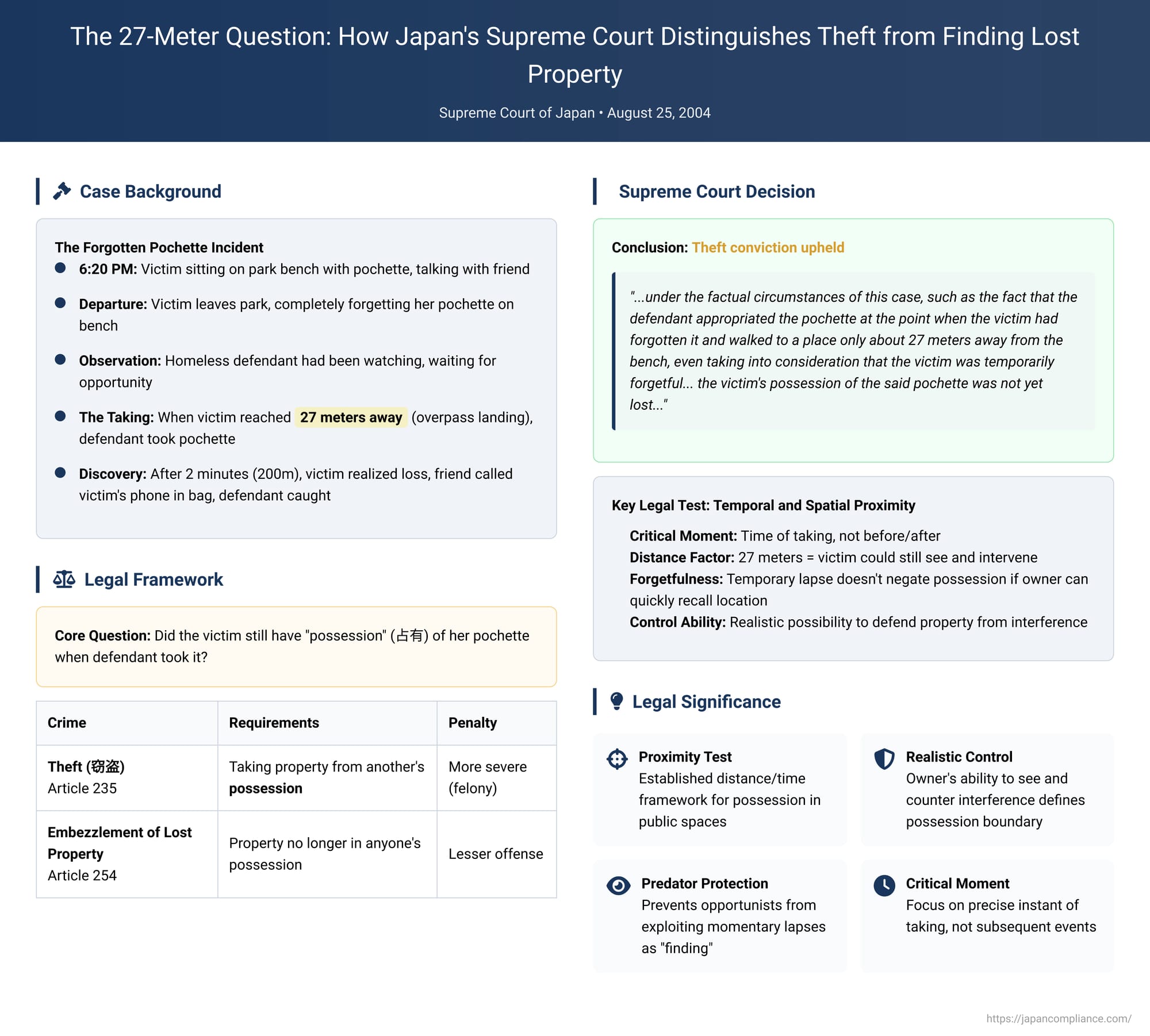

The 27-Meter Question: How Japan's Supreme Court Distinguishes Theft from Finding Lost Property

Imagine you are sitting on a park bench, deep in conversation with a friend. When you get up to leave, you inadvertently leave your bag behind. A person who was watching you waits for you to get a short distance away and then snatches it. Are they a thief who has stolen your property, or have they simply found a "lost" item? This fine line is a critical distinction in criminal law, separating the serious felony of theft from the lesser offense of embezzlement of lost property.

This very scenario was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on August 25, 2004. The case, involving a forgotten pochette in a public park, forced the Court to clarify the precise moment an owner loses legal "possession" of their property. In its ruling, the Court established a clear and practical framework centered on the concepts of time, distance, and the owner's ability to realistically control their belongings, even when momentarily forgotten.

The Facts of the Case: The Forgotten Pochette

On the evening of the incident, the victim was sitting on a park bench with her pochette (a small handbag) beside her, talking with a friend. At around 6:20 PM, she left the park with her friend, heading toward the nearby train station, but she completely forgot her pochette, leaving it on the bench.

The defendant, who was homeless and had been looking for an opportunity to commit a theft by snatching a bag, had been observing the victim. He watched as she and her friend walked away from the bench and up onto a pedestrian overpass. When the victim had reached the landing of the overpass stairs, a distance of approximately 27 meters from the bench, the defendant saw his chance. Checking that no one else was around, he took the pochette and went into a public restroom in the park to rifle through its contents.

Meanwhile, the victim continued walking. After about two minutes, having covered a distance of roughly 200 meters to the station's ticket gate, she suddenly realized she had left her pochette behind. She immediately ran back to the bench, only to find the bag gone. In a moment of quick thinking, her friend used her own cell phone to call the victim's phone, which was inside the stolen pochette. The phone began to ring from inside the public restroom, and the startled defendant emerged. He was confronted by the victim, admitted to the crime, and was handed over to the police.

The Legal Crossroads: Theft vs. Embezzlement of Lost Property

The defendant was charged with theft. However, the core legal question was whether his act truly constituted theft or the lesser crime of embezzlement of lost property. The distinction is fundamental:

- Theft (settō - Article 235 of the Penal Code): This crime requires the "theft" (setshu) of property from another person's possession. It involves violating an existing state of control.

- Embezzlement of Lost Property (sen'yū ridatsubutsu ōryō - Article 254): This crime applies to property that is no longer in anyone's possession—items that have been truly lost or abandoned.

The entire case therefore hinged on the legal definition of "possession" (sen'yū) in criminal law. Did the victim still have possession of her pochette when the defendant took it, even though she had forgotten it and was walking away?

The Supreme Court's Crucial Clarification: The Moment of the Taking

The Supreme Court upheld the defendant's conviction for theft, affirming the lower court's conclusion. However, it subtly but importantly refined the legal reasoning. The key to the Court's decision was its focus on the precise moment in time when the criminal act occurred.

The lower High Court had considered the entire sequence of events, including the short time and distance before the victim recovered the bag. The Supreme Court, however, pinpointed the legally relevant moment: the instant the defendant appropriated the pochette. At that specific point, the victim was only 27 meters away. This clarification is the ruling's most significant contribution; the question is not what happens after the fact, but whether possession existed at the moment the crime was committed.

The Court stated:

"...under the factual circumstances of this case, such as the fact that the defendant appropriated the pochette at the point when the victim had forgotten it and walked to a place only about 27 meters away from the bench, even taking into consideration that the victim was temporarily forgetful of the pochette and was leaving the scene, the victim's possession of the said pochette was not yet lost..."

The Litmus Test: Temporal and Spatial Proximity

The Court's decision establishes "temporal and spatial proximity" as the primary test for determining whether possession is maintained over an item left in a public place. But why does this physical closeness matter in a legal sense?

Legal analysis explains that proximity is a proxy for the owner's "realistic possibility of control". An even more advanced view, which helps to clarify the principle, frames it in terms of the owner's "ability to counter an infringement on possession". If an owner is close enough to see a potential theft and intervene to protect their property, they are still exercising a form of control, and thus, possession has not been lost.

In this case, 27 meters was deemed a distance from which the victim could have seen the defendant's act and challenged him. This potential to defend her property is the substantive reason why her possession was considered to be continuous. This principle has been applied in subsequent cases; for instance, a 2017 High Court decision denied a theft conviction where the distance was 90 meters and the owner could no longer see the location, as their ability to counter any infringement was gone.

What About Forgetfulness?

The Supreme Court explicitly took the victim's forgetfulness into account but found it did not negate her possession. The commentary on the case explains that the owner's awareness of the item's location, even if temporarily lapsed, is a secondary factor supporting the "ability to counter". Because the victim knew exactly where she had left the pochette, she was able to immediately recall its location and run back to protect it once she realized it was missing. This ability to quickly regain awareness and take action reinforces the idea that her control was not fully severed. Had she left it somewhere and had no idea where it could be, her claim to possession would be far weaker.

Conclusion: A Framework for Defining Possession

The 2004 Supreme Court decision provides a clear and practical framework for drawing the line between a temporarily forgotten item and a legally "lost" one. It teaches three key principles:

- The critical moment for assessing possession is the time of the taking, not what happens before or after.

- In a public space, the primary test for possession is the temporal and spatial proximity between the owner and the object at that critical moment.

- The underlying reason this test works is that proximity serves as an indicator of the owner's ability to realistically control or defend the property from interference.

This ruling ensures that the law correctly identifies those who prey on a person's momentary lapse of attention as thieves, not as mere finders of lost property. It affirms that possession is not just about physical touch, but about the continuing, realistic sphere of control a person has over their belongings.