The 1976 Malapportionment Ruling: Japan's Supreme Court Confronts Unequal Votes and the Limits of Judicial Remedy

Date of Judgment: April 14, 1976

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

Introduction

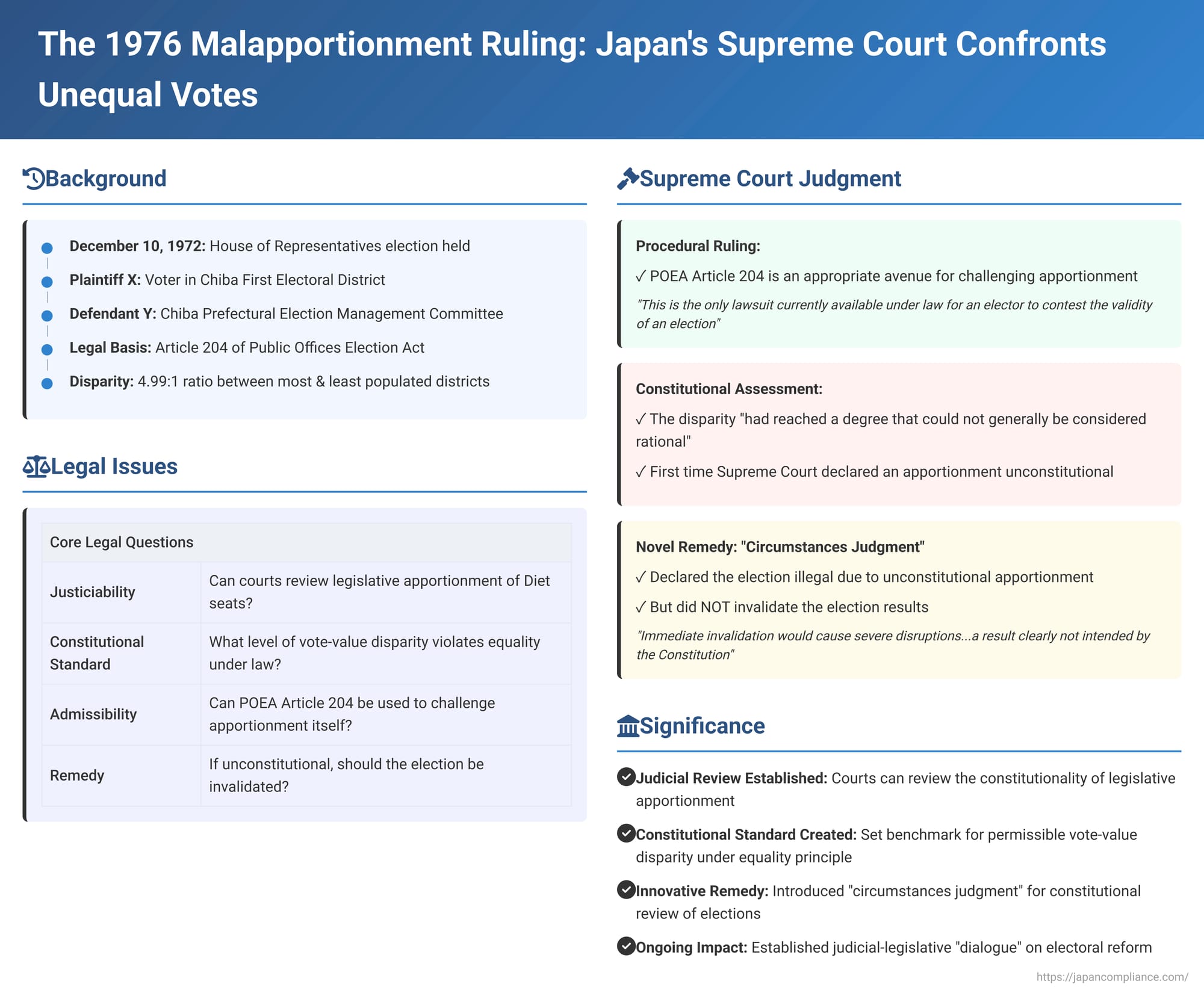

On April 14, 1976, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a seminal decision that reverberated through the nation's legal and political landscape. The case, commonly known as the 1976 Malapportionment Ruling, addressed the constitutionality of Japan's then-existing system for apportioning seats in the House of Representatives. It grappled with profound questions: How much disparity in the value of individual votes is constitutionally permissible? What legal avenues are available to citizens to challenge a fundamentally unfair apportionment? And, if an apportionment scheme is found unconstitutional, what is the appropriate judicial remedy, especially concerning an election already held under that scheme? This landmark decision marked the first time Japan's highest court declared a legislative seat apportionment unconstitutional due to vote-value inequality. In doing so, it also pioneered the use of a "circumstances judgment" in this specific context, attempting to balance constitutional demands with pragmatic concerns about governmental stability.

I. Background: The Disputed Election and Claims of Inequality

The legal challenge arose from perceived unfairness in Japan's electoral system.

The Election in Question:

The lawsuit specifically concerned the general election for Japan's House of Representatives (the lower house of the National Diet) that was held on December 10, 1972.

The Plaintiff:

The plaintiff, X, was an elector (a registered voter) in the Chiba Prefecture First Electoral District. This status as an elector was crucial to X's standing to bring the suit.

The Defendant:

The defendant, Y, was the Chiba Prefectural Election Management Committee, the body responsible for administering elections in that prefecture.

The Legal Basis of the Suit:

X filed the lawsuit under the provisions of Article 204 of Japan's Public Offices Election Act (POEA). This article provides a legal mechanism for electors and candidates to challenge the validity of an election or the success of a particular candidate.

X's Core Arguments for Invalidating the Election:

The plaintiff's case was built on two principal contentions:

- Unconstitutional Apportionment: X argued that the existing apportionment of seats for the House of Representatives, as stipulated in Schedule 1 and other related provisions of the POEA, was fundamentally unconstitutional. The core of this argument was that the apportionment scheme led to significant disparities in the number of voters per Diet member across different electoral districts. This, X contended, violated Article 14 of the Constitution of Japan, which guarantees equality under the law, by treating citizens in different electoral districts unequally without any rational or justifiable basis, thereby diluting the weight of votes in more populous districts compared to less populous ones.

- Invalidity of the Election: Flowing from the first point, X argued that because the December 1972 election was conducted under these unconstitutional apportionment provisions, the election itself was invalid and should be nullified by the court, at least in the Chiba First Electoral District.

II. The Path Through Lower Courts and Y's Counterarguments

The defendant electoral committee mounted a robust defense, challenging both the justiciability of the claim and its merits.

Y's Defense Strategy:

The Chiba Prefectural Election Management Committee (Y) presented several arguments against X's lawsuit:

- Preliminary Objections (Challenging the Court's Jurisdiction or the Suit's Propriety):

- Firstly, Y argued that the issue of legislative seat apportionment was a "highly political question" (kōdo no seiji mondai). This invoked a concept similar to the political question doctrine seen in other jurisdictions, suggesting that such matters are best left to the political branches of government (i.e., the Diet) and fall outside the proper scope of judicial review.

- Secondly, Y contended that a lawsuit initiated under POEA Article 204 was not the appropriate legal mechanism for an elector to challenge the constitutionality of the apportionment statute itself; rather, such suits were intended for challenging irregularities in the conduct of an election under existing law.

- On the Merits (Defending the Existing Apportionment): Y argued that while some disparities in the number of voters per Diet member across different electoral districts might exist, these had not yet reached a level that would constitute an unconstitutional inequality of the right to vote.

Tokyo High Court's Decision:

Lawsuits seeking to nullify Diet elections are, under Japanese law, filed directly with a High Court as the court of first instance. The Tokyo High Court heard X's case and rejected Y's preliminary objections concerning justiciability and the propriety of the suit under POEA Article 204. This meant the High Court affirmed its competence to hear the case and proceeded to a substantive review of the plaintiff's claims regarding vote-value disparity.

However, after this substantive review, the Tokyo High Court ultimately dismissed X's claim. It found that the inequality in voting value, while present, had not yet reached a degree that could be deemed constitutionally impermissible. It was from this judgment of the Tokyo High Court that X appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

III. The Supreme Court's Landmark Adjudication

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court delivered a multifaceted and groundbreaking judgment that fundamentally altered the landscape of electoral litigation and constitutional review in Japan.

A. Admissibility of Challenging Apportionment via POEA Article 204

The Supreme Court first decisively addressed the crucial procedural question: could an elector indeed use POEA Article 204 as a vehicle to challenge the constitutionality of the legislative apportionment statute itself, as a ground for nullifying an election?

- The Court affirmed the suitability of this legal avenue. It reasoned that such a lawsuit under POEA Article 204 "is the only lawsuit currently available under law for an elector to contest the validity of an election".

- The Court further emphasized that "apart from this, there is no other opportunity to judicially assert the unconstitutionality of the Public Offices Election Act and seek its correction". This highlighted the lack of alternative judicial pathways for citizens to address such fundamental constitutional grievances concerning their voting rights.

- Invoking a broader constitutional principle of ensuring access to justice, the Supreme Court stated: "in light of the constitutional demand that avenues for redress and relief should be as open as possible against acts of state power that infringe upon the fundamental rights of the people, it cannot be considered a sound interpretation that the aforementioned provision of the Public Offices Election Act specifically intends to exclude, in the lawsuits it prescribes, the assertion that the apportionment of Diet member seats violates electoral equality as a cause for election nullification". This was a purposive interpretation, ensuring that a right did not exist without a potential remedy.

- The PDF commentary points out that while prior Supreme Court decisions concerning malapportionment in the House of Councillors (the upper house) had permitted such suits without extensive supporting reasoning, this 1976 judgment provided a more thorough and principled justification for allowing such challenges under POEA Article 204.

B. The Unconstitutionality of the Existing Apportionment

Having confirmed the appropriateness of the lawsuit, the Supreme Court proceeded to a substantive examination of the principle of electoral equality and the constitutionality of the apportionment scheme used in the 1972 election.

- It unequivocally affirmed that Article 14, paragraph 1 of the Constitution (guaranteeing equality under the law), when applied to the right to vote (itself guaranteed by Articles 15 and 44 of the Constitution), demands equality in the value of each person's vote. This means that each vote should carry, as far as practically possible, the same weight in influencing the outcome of an election.

- The Court acknowledged that achieving perfect mathematical equality in vote value is practically unattainable in any system that uses electoral districts. It also recognized that the Diet (Japan's parliament) possesses considerable discretion in designing the specific electoral system, taking into account a variety of factors such as geography, administrative divisions, historical precedent, population density, and the need to balance representation with effective governance.

- However, the Supreme Court made it clear that this legislative discretion is not unlimited and must operate within constitutional bounds. After reviewing the evidence, the Court found that by the time of the December 1972 election, the disparities in the number of voters per Diet member across different electoral districts had become excessively severe. The ratio between the most populated district per seat and the least populated district per seat had reached approximately 4.99 to 1.

- This level of disparity, the Court concluded, "had reached a degree that could not generally be considered rational, even taking into account various factors such as policy discretion regarding rapid social changes." In other words, the existing inequalities had crossed the threshold of what could be justified by any legitimate policy considerations.

- Furthermore, the Supreme Court pointed to the Diet's failure to rectify this significant and growing imbalance within a "constitutionally reasonable period." The apportionment provisions at issue largely originated from a 1964 amendment to the POEA. Despite the POEA itself containing a provision suggesting a review of seat distribution every five years based on the latest national census results, more than eight years had passed since the 1964 revision without any corrective legislative action to address the mounting disparities.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court declared that the apportionment provisions of the POEA that governed the 1972 House of Representatives election were, at the time of that election, in violation of the constitutional requirement of electoral equality and were thus unconstitutional. It also importantly noted that because legislative seat apportionment is an interconnected system for the entire nation, this unconstitutionality tainted the apportionment provisions as a whole, not just in the most egregiously malapportioned districts.

C. The Remedy: Introducing the "Circumstances Judgment" in Election Cases

Having found the apportionment statute unconstitutional, the Supreme Court faced the critical and complex question of what this meant for the validity of the 1972 election held under it. Article 98 of the Constitution of Japan declares that the Constitution is the supreme law of the nation and that any law or act contrary to its provisions shall have no legal force or validity.

- A straightforward application of Article 98 might suggest that an election held under an unconstitutional law should be declared null and void. However, the Court recognized the profound and potentially chaotic consequences of such a direct nullification of a national election. It reasoned that simply invalidating the election would not, in itself, automatically bring about a constitutional state of electoral affairs.

- Instead, such a nullification could lead to a cascade of severe disruptions: all Diet members elected under those rules could potentially lose their legitimately held status, the validity of laws passed by that Diet could be called into question, and the Diet itself might become unable to function, including being unable to pass the very legislative amendments needed to correct the unconstitutional apportionment. This, the Court emphatically stated, would be "a result clearly not intended by the Constitution."

- In navigating this dilemma, the Supreme Court turned to a legal principle analogous to the "judgment based on special circumstances" (jijō hanketsu) found in Article 31, paragraph 1 of Japan's Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA). This ACLA provision allows a court, even if it finds an administrative disposition (an administrative act) to be illegal, to refrain from revoking it if doing so would cause "significant impediment to the public interest" and be contrary to the public welfare, after a comprehensive consideration of all relevant circumstances.

- The Court explicitly acknowledged that ACLA Article 31 is, by the terms of POEA Article 219, excluded from direct application to election lawsuits brought under the POEA. It interpreted this statutory exclusion as reflecting a legislative judgment that when an election merely violates the procedural provisions of the POEA itself (e.g., errors in vote counting or campaign rule violations), nullification is generally considered to be in the public interest to ensure that lawful re-elections are held.

- However, the Supreme Court distinguished the present case from such ordinary POEA violations. Here, the defect was not a mere procedural irregularity committed by election officials, but rather a fundamental constitutional flaw embedded in the POEA itself—a general defect whose correction required legislative amendment by the Diet. In such exceptional circumstances, where the unconstitutionality stemmed from the law itself and the consequences of nullification were so severe, the Court found that the underlying general legal principle of avoiding extreme public detriment (which informs ACLA Article 31) could, and should, be applied by analogy.

- Balancing the finding of unconstitutionality against the potential for systemic disruption, the Supreme Court decided that "it is appropriate in this case, following the aforementioned legal principle, to limit its ruling to a declaration that the election in question was illegal in that it was conducted under apportionment provisions that violate the Constitution, and not to invalidate the election itself".

- Consequently, the Supreme Court modified the judgment of the Tokyo High Court. While X's ultimate request to nullify the election was dismissed, the Supreme Court, in the main operative text (shubun) of its own judgment, formally declared that the December 1972 House of Representatives election in the Chiba First Electoral District was illegal due to the unconstitutional apportionment.

IV. Broader Context and Legal Debates

The 1976 Supreme Court ruling on malapportionment was not delivered in a vacuum. It touched upon several complex legal and constitutional issues that continue to be debated.

Nature of Election Apportionment Lawsuits:

- As the PDF commentary relating to this case explains, lawsuits concerning public office elections in Japan, such as the one initiated by X under POEA Article 204, are generally classified in legal doctrine as "people's actions" (minshū soshō) or, more broadly, as a form of "objective litigation" (kyakkan soshō). Unlike "subjective litigation," which is primarily aimed at protecting an individual plaintiff's personal rights or redressing a specific infringement they have suffered, objective litigation serves a broader public interest by seeking to ensure the general legality and proper functioning of the electoral system or other public institutions. Because they are not necessarily tied to a direct, personal injury in the traditional sense, such objective lawsuits typically require specific statutory authorization to be admissible in court. POEA Article 204 provides this necessary statutory basis for citizens to challenge the validity of an election.

The "Political Question" Doctrine and Justiciability:

- A frequently raised defense by the government in malapportionment cases is the argument that legislative apportionment is a "highly political question" inherently unsuitable for judicial resolution, and that such matters should be left to the discretion of the legislature. The Tokyo High Court, in its handling of X's case, had rejected this argument, asserting its competence to review matters that directly concern the fundamental right to vote. The Supreme Court, by proceeding to make a substantive ruling on the merits of the constitutional claim (i.e., whether the apportionment was indeed unconstitutional), implicitly affirmed the justiciability of such issues, thereby declining to treat malapportionment as a non-justiciable political question in this instance. It is noteworthy that one of the dissenting opinions in the Supreme Court also explicitly stated that when the Diet's exercise of its discretionary power in apportionment "grossly lacks rationality and reaches a state contrary to the demands of the Constitution, it cannot escape judicial judgment," further supporting the judiciary's role. The PDF commentary suggests that while the majority opinion of the Supreme Court did not engage in an extensive discussion of the political question doctrine, its willingness to make a substantive constitutional determination implies a rejection of the doctrine's applicability to the case at hand.

Efficacy of the Remedy and the "Circumstances Judgment":

- A significant and persistent debate surrounding these malapportionment lawsuits concerns the actual effectiveness of the remedy provided by POEA Article 204, particularly when the root of the problem is the unconstitutionality of the apportionment statute itself. If a court were to simply nullify an election, the POEA generally requires a re-election to be held within 40 days. However, amending the apportionment statute—a complex legislative task involving political negotiations and parliamentary procedures—is practically impossible to achieve within such a short timeframe. This practical impossibility led to arguments, as noted in the PDF commentary, that such lawsuits should be dismissed as futile because they couldn't lead to a lawful re-election without prior legislative reform, which is outside the court's direct control. The Tokyo High Court had characterized this argument as "putting the cart before the horse," a view implicitly endorsed by the Supreme Court when it admitted the suit.

- The Supreme Court's adoption of the "circumstances judgment" in this 1976 case was a novel and pragmatic attempt to navigate this difficult dilemma. By declaring the election illegal due to the unconstitutional statute but refraining from voiding the election results, the Court sought to send a powerful message to the Diet about the unconstitutionality of the existing state of affairs and the urgent need for legislative reform, without causing the immediate political paralysis that a full nullification might entail. However, the PDF commentary candidly points out that this "circumstances judgment" solution is not without its own set of inherent difficulties and criticisms. If the Diet fails to act or acts inadequately despite such judicial declarations, the repetition of "circumstances judgments" in subsequent cases might not, by itself, ensure an effective or timely remedy for the underlying constitutional violation. This has led to ongoing scholarly discussions and debates about alternative judicial approaches that might be more effective in compelling legislative action, such as the possibility of courts issuing prospective rulings (e.g., declaring an apportionment unconstitutional but giving the legislature a specific deadline to act before an election is definitively nullified) or considering partial nullifications, though these alternatives also present their own considerable legal and practical complexities.

Alternative Procedural Approaches Considered by Dissenting Opinions:

- The PDF commentary draws attention to the fact that at least one dissenting justice in the 1976 ruling (Justice Kishi) raised profound questions about the inherent suitability of using POEA Article 204 as the procedural vehicle for these types of fundamental constitutional challenges to apportionment. This dissenting opinion suggested that malapportionment lawsuits possess a unique dual character, exhibiting aspects of both "people's actions" (objective litigation aimed at ensuring overall electoral legality) and "administrative complaint litigation" (kōkoku soshō) (which is typically subjective litigation where individual plaintiffs seek redress for infringements of their specific rights, and in this context, voters might be seen as having their individual right to an equal vote infringed).

- Justice Kishi's opinion explored the idea that procedures under the Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA) might offer a more fitting framework for such claims. This could potentially be achieved by conceptualizing the entire election process, or perhaps the final certification of election winners, as an "administrative disposition" (gyōsei shobun) subject to challenge under ACLA. Alternatively, it was even suggested that the apportionment statute itself, given its direct and binding impact on defining electoral districts and representation, might be viewed as a form of "general disposition" (ippan shobun) amenable to a direct challenge under ACLA procedures. If such an ACLA-based approach were adopted, it might open up different remedial possibilities than those traditionally available under the more limited scope of POEA Article 204. However, the PDF commentary also prudently acknowledges that since the POEA Article 204 route has become the established, albeit imperfect, avenue for these malapportionment cases, it could be argued that the existence of this specific remedy (however flawed) might preclude resort to more general ACLA procedures, based on principles such as a specific law overriding a general one, or the idea that an adequate specific remedy (even if not ideal) already exists.

V. Legacy and Subsequent Developments

The 1976 Supreme Court ruling was undeniably a watershed moment in Japanese constitutional law and has had a lasting impact on the country's electoral jurisprudence.

- It powerfully affirmed the judiciary's role and responsibility in scrutinizing the constitutionality of legislative apportionment, thereby championing the fundamental democratic principle of voting equality. While the Court continued to acknowledge that the Diet possesses broad legislative discretion in the intricate task of designing electoral systems, this decision firmly established that such discretion is not absolute and must yield when disparities in vote value become so excessive as to be deemed irrational and constitutionally offensive.

- In the years following this landmark precedent, the Supreme Court of Japan has issued numerous other rulings on challenges to Diet seat apportionment. In several of these subsequent cases, the Court has found that "states of unconstitutionality" (iken jōtai) existed, a finding that indicates the disparities, though perhaps not severe enough to warrant immediate nullification of an election via a "circumstances judgment," were nonetheless significant enough to require prompt legislative correction by the Diet. In some later cases concerning the House of Representatives, the Court has again gone further, explicitly declaring prevailing apportionment schemes unconstitutional, similar to its stance in the 1976 decision.

- The Supreme Court has also engaged with the constitutionality of specific apportionment formulas and methodologies adopted by the Diet, such as the "one-person, one-vote plus allocation for prefectural representation" method (often referred to as the "Adams method" variant used in Japan). In some instances, the Court has found that an apportionment scheme that might have been considered permissible at one point in time subsequently became unconstitutional due to evolving demographic realities (such as continued population shifts to urban areas) coupled with the Diet's prolonged inaction in addressing the resultant vote-value imbalances.

- The 1976 judgment, and particularly its innovative use of the "circumstances judgment" as a remedial tool, continues to be a subject of intense legal and academic discussion and debate in Japan. It reflects the ongoing and delicate tension the judiciary faces in attempting to uphold fundamental constitutional rights while simultaneously striving to maintain governmental stability and avoid precipitating immediate political crises. The ruling underscores the judiciary's complex role in prompting and guiding necessary legislative reform in the sensitive area of electoral democracy, often described as fostering a "dialogue" between the judicial and legislative branches of government, a dialogue that continues to shape and refine Japan's democratic processes.

VI. Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's April 14, 1976, decision in the Chiba malapportionment case stands as a critical marker in the nation's constitutional and electoral jurisprudence. It was a courageous and groundbreaking moment, as it marked the first instance in which the country's highest court declared the National Diet's seat apportionment unconstitutional due to severe vote-value inequality, thereby forcefully championing the democratic ideal of "one person, one vote" as a substantive constitutional mandate.

By simultaneously employing a "circumstances judgment"—a nuanced legal tool allowing it to declare the election illegal due to the unconstitutional law but refraining from voiding the election results outright—the Court navigated a complex and perilous path. This approach attempted to uphold core constitutional principles and signal the urgent need for legislative reform, without plunging the nation into immediate political chaos that could have resulted from a wholesale nullification of a national election.

This pivotal ruling firmly opened the door for ongoing judicial scrutiny of legislative apportionment in Japan. It established a dynamic, often described as an inter-branch "dialogue," between the judiciary and the Diet concerning the fundamental requirements of electoral fairness, a dialogue that persists to this day and continues to shape the contours of Japan's democratic processes.