Tenant's Right to Demand Building Purchase Post-Eviction Judgment: A Japanese Supreme Court Clarification

In Japanese landlord-tenant law, particularly concerning leased land, tenants who have constructed buildings on that land are afforded certain protections upon the termination of their lease. One significant protection is the "building purchase demand right" (建物買取請求権 - tatemono kaitori seikyūken). This statutory right allows a tenant, under specific conditions (typically lease expiration without renewal, where the tenant hasn't breached the lease), to demand that the landlord purchase the buildings on the leased land at their current market value. This prevents the tenant from losing their entire investment in the building and promotes the efficient use of existing structures.

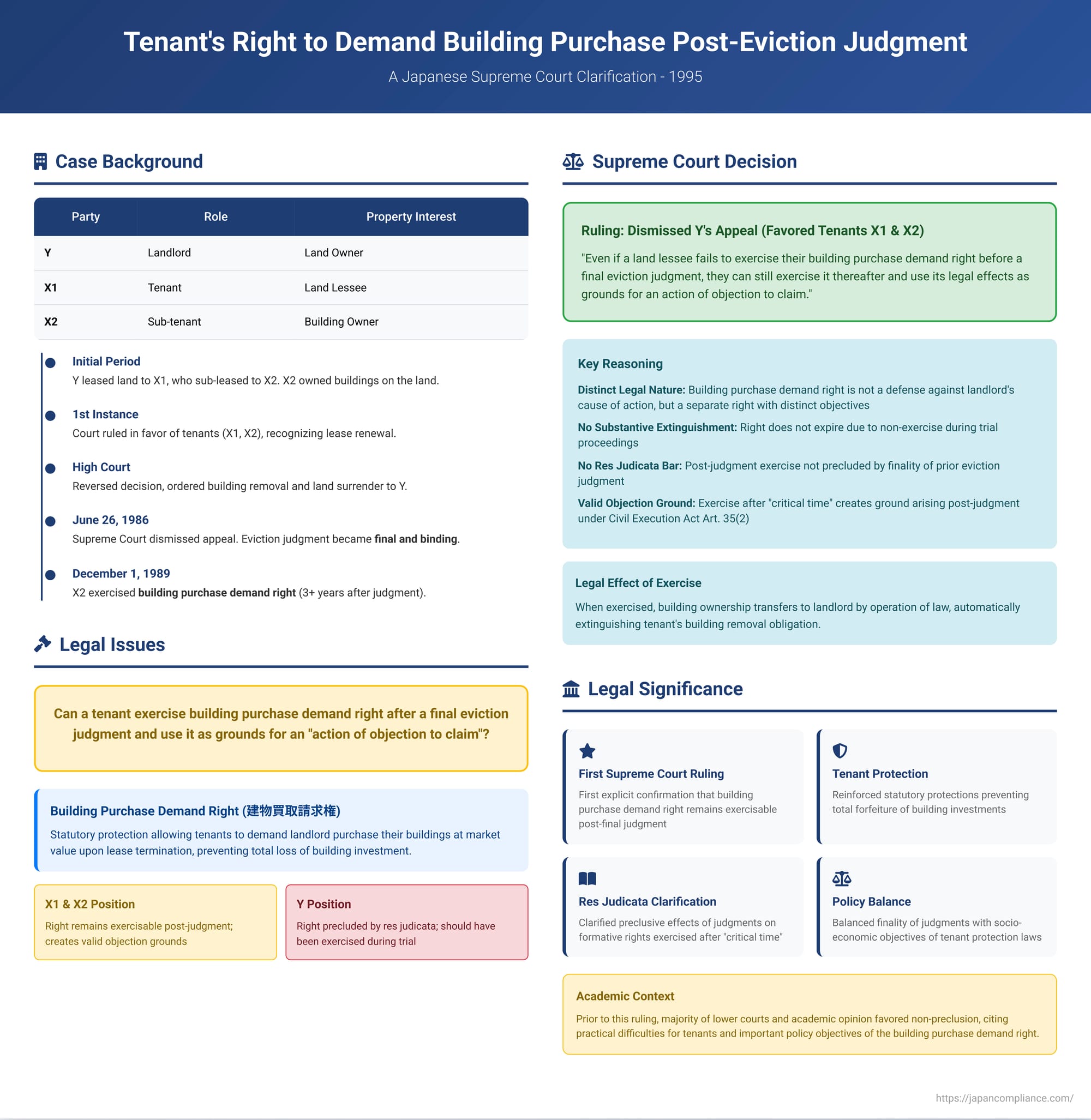

A crucial legal question arises when a landlord has already obtained a final and binding court judgment ordering the tenant to remove the buildings and surrender the land. If the tenant failed to exercise this building purchase demand right before that judgment became final, are they then barred from doing so? And if they do exercise it post-judgment, can this act serve as a valid ground to object to the enforcement of the eviction judgment through an "action of objection to claim" (請求異議の訴え - seikyū igi no uttae)? A 1995 Supreme Court of Japan decision provided a clear and significant answer to these questions.

Background of the Dispute

The case involved a parcel of land owned by Y (the landlord). Y had leased this land to X1 (the tenant), who in turn sub-leased it to X2 (the sub-tenant). X2 owned several buildings on this land, which X2 then leased out to other parties (A and others).

The landlord, Y, initiated a lawsuit against X1 (based on the expiration of the primary lease term) and against X2 (based on Y's land ownership rights) seeking the removal of the buildings and the surrender of the land.

- The first instance court initially ruled in favor of the tenants, X1 and X2, recognizing a renewal of the lease and dismissing Y's claim for building removal and land surrender.

- However, on appeal, the High Court overturned this decision and ruled in favor of the landlord, Y, ordering X1 and X2 to remove the buildings and surrender the land.

- X1 and X2 appealed to the Supreme Court, but their appeal was dismissed on June 26, 1986, making the High Court's judgment in favor of Y (ordering eviction) final and binding.

Subsequently, on December 1, 1989—more than three years after the eviction judgment against them became final—X2 formally exercised the statutory building purchase demand right by sending a written notice to the landlord, Y. This right was asserted under Article 4, Paragraph 2 of the then-Leased Land Act (which has since been incorporated into Article 13, Paragraphs 1 and 3 of the current Leased Land and House Lease Act).

Following this, X1 and X2 initiated a new lawsuit against Y: an "action of objection to claim" under Article 35 of the Civil Execution Act. They argued that Y should not be allowed to enforce the prior eviction judgment because X2's exercise of the building purchase demand right had fundamentally altered the legal situation.

The Osaka District Court and, subsequently, the Osaka High Court both ruled in favor of X1 and X2 in this action of objection, agreeing that the exercise of the building purchase demand right rendered the prior eviction judgment unenforceable. The landlord, Y, then appealed this outcome to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court of Japan dismissed the landlord Y's appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' decisions that favored the tenants X1 and X2. The Court established a clear principle:

Even if a land lessee who owns buildings on the leased land fails to exercise their statutory building purchase demand right by the time oral arguments are concluded in the factual trial of a building removal and land surrender lawsuit initiated by the lessor, and even if a judgment is subsequently rendered in favor of the lessor ordering such removal and surrender and that judgment becomes final and binding, the lessee can still exercise the building purchase demand right thereafter. Furthermore, after exercising this right, the lessee is entitled to file an action of objection to claim against the lessor, seeking to prevent the enforcement of the said final judgment, and can validly assert the legal effects of the exercised building purchase demand right as a ground for their objection.

The Supreme Court provided the following detailed reasoning for its decision:

- Distinct Nature of the Building Purchase Demand Right: The Court emphasized that the building purchase demand right is not a defense aimed at highlighting a defect inherent in the lessor's original cause of action for building removal and land surrender (the right to which was confirmed by the prior final judgment). Instead, the building purchase demand right is a distinct legal right that arises based on separate institutional objectives and distinct legal grounds (namely, the provisions of the Leased Land Act designed to protect tenant investments and ensure the continued use of valuable buildings). When the lessee exercises this right, the ownership of the building automatically transfers by operation of law to the lessor. As a direct legal consequence of this transfer of ownership, the lessee's obligation to remove the building is extinguished.

- No Substantive Extinguishment or Procedural Preclusion:

- Substantive Law Perspective: The fact that the lessee did not exercise their building purchase demand right by the conclusion of oral arguments in the prior eviction lawsuit does not, under substantive law, cause the extinguishment of that right. The Supreme Court cited its own 1977 precedent (Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, June 20, 1952, Saibanshu Minji No. 121, p. 63) to support this point.

- Procedural Law Perspective (Res Judicata): From a procedural standpoint, the assertion of the building purchase demand right after the prior judgment is not barred by the res judicata (preclusive effect) of that prior final judgment.

- A Ground for Objection Arising After the "Critical Time":

Consequently, when a lessee exercises their building purchase demand right after the conclusion of oral arguments in the factual trial of the prior eviction lawsuit (this conclusion of oral arguments being the "critical time" for res judicata purposes), this act legally extinguishes the lessee's building removal obligation which had been confirmed by the prior final judgment. To that extent, the prior final judgment loses its executory force. Therefore, the legal effect of exercising the building purchase demand right constitutes a "ground of objection that arose after the conclusion of oral arguments" as stipulated in Article 35, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Execution Act. This makes it a valid basis for an action of objection to claim.

Significance and Analysis of the Decision

This 1995 Supreme Court decision is a landmark ruling that significantly clarified the interplay between the finality of judgments and the statutory protections afforded to tenants under Japanese leased land law.

- First Supreme Court Confirmation on This Specific Issue: It was the first time the Supreme Court explicitly ruled that a building purchase demand right remains exercisable even after a final judgment ordering building removal and land surrender has been issued against the tenant, and that its subsequent exercise can form a valid basis for an action of objection to claim to prevent enforcement of that judgment.

- Understanding Res Judicata and its Preclusive Effect (遮断効 - shadankō):

An "action of objection to claim" (Civil Execution Act, Article 35) is a vital remedy for a judgment debtor. It allows them to challenge the enforcement of a title of obligation if there is a discrepancy between what the title mandates and the current substantive legal reality—for example, if the debt recorded in a judgment has been paid after the judgment was rendered.

However, when the title of obligation is a final and binding judgment, the doctrine of res judicata comes into play. Res judicata prevents the parties from re-litigating issues that were, or could have been, decided in the prior lawsuit. Its "preclusive effect" (shadankō) generally means that facts that existed before the "critical time" (the conclusion of oral arguments in the factual trial of the prior suit) cannot be raised as new grounds for objection in a later proceeding concerning the same claim. Article 35, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Execution Act reflects this by limiting objections against a final judgment to grounds that arose after this critical time.

A key debate in Japanese civil procedure has centered on "formative rights" (形成権 - keiseiken)—rights that, upon unilateral exercise by the right-holder, create, alter, or extinguish legal relationships (e.g., a right to rescind a contract, a right of set-off, or this building purchase demand right). If the factual basis for such a formative right existed before the critical time in a prior lawsuit, but the right was not exercised until after the critical time, is its subsequent exercise (and the legal consequences flowing from it) precluded by res judicata? The Supreme Court's stance has varied for different types of formative rights. For instance, it had previously denied preclusion for the right of set-off when exercised post-judgment but had affirmed preclusion for a right of rescission. This 1995 decision definitively placed the building purchase demand right in the non-precluded category, allowing its post-judgment exercise to serve as a valid objection. - Prevailing Views Before This Ruling:

The PDF commentary notes that prior to this Supreme Court judgment, a majority of lower court rulings had already leaned towards not precluding the post-judgment exercise of the building purchase demand right. The common reasons cited by these lower courts included: (i) the building purchase demand right is not an inherent defense (kōbenken) against the landlord's fundamental claim for land surrender itself (but rather a separate statutory mechanism), and (ii) the important socio-economic purposes of the right—allowing tenants to recoup their capital investment in buildings and preserving the social utility of these structures—should be respected and not easily forfeited. The High Court in the present case had also considered the specific litigation history, noting that the tenants could not necessarily be blamed for not exercising the right earlier, especially since they had initially won at the first instance of the eviction suit.

Academic opinion had also largely favored non-preclusion. In addition to the reasons cited by lower courts, scholars pointed to the practical difficulty for tenants (who may lack sophisticated legal knowledge) to proactively exercise a right that, in effect, concedes the termination of their lease and their eventual loss of possession, particularly while they are still fighting the eviction itself. Some scholars adopt a broader stance, arguing that res judicata only confirms the existence (or non-existence) of the specific claim adjudicated as of the critical time; it does not confirm that the claim is immune to any future extinguishment by the exercise of any formative right. From this perspective, no formative right should be precluded by res judicata merely because it could have been exercised earlier.

Conversely, a minority view favored preclusion, emphasizing the need for legal stability and arguing that the building purchase demand right, if available, should be raised as a defense during the eviction proceedings, similar to other defenses. Proponents of this view also argued that tenants have a responsibility to exercise their known rights in a timely manner. - Analysis of the Supreme Court's Reasoning in the 1995 Decision:

The Supreme Court’s reasoning in point (1) of its decision—distinguishing the building purchase demand right from "defects inherent in the cause of action" for eviction—is particularly important. This phrasing consciously differentiates the building purchase demand right from, for example, a right of rescission (which the Court had previously held to be subject to preclusion if not timely exercised). Exercising a right of rescission aims to nullify the original cause of action from its inception. In contrast, exercising the building purchase demand right does not negate the landlord's original right to terminate the lease; rather, it creates a new set of legal relationships (transfer of building ownership to the landlord, landlord's obligation to pay the purchase price) that arises as a consequence of the lease termination.

The Court’s emphasis on the "separate institutional objectives and causes" underlying the building purchase demand right (such as protecting the building itself and the tenant's investment) demonstrates that it took substantive policy considerations into account, a stance consistent with previous judicial trends concerning this particular right.

It is also noteworthy that the Supreme Court did not adopt the High Court's line of reasoning that focused on whether the tenants in this specific case could be blamed for not exercising their right earlier due to the particular course of the prior litigation. By omitting this, the Supreme Court appears to have established a more general rule of non-preclusion for the building purchase demand right, irrespective of the specific litigation tactics or circumstances of the prior case. The PDF commentary suggests this approach is appropriate, as making preclusion dependent on such case-specific assessments could undermine the objective and uniform application of res judicata. Any potential abuse of the late exercise of the building purchase demand right could, if necessary, be addressed under general legal principles such as the doctrine of abuse of rights or the principle of good faith. - Effect on the Original Judgment and the Form of Decree in the Action of Objection:

The Supreme Court stated that when the building purchase demand right is exercised, "the lessee's building removal obligation is extinguished, and the prior final judgment loses its executory force to that extent." This language suggests a partial extinguishment of the obligations under the original judgment.

In the specific facts of this case, the tenants (X1 and X2) had, concurrently with exercising the purchase demand right, also transferred possession of the buildings to the landlord (Y). By doing so, they had effectively performed their new obligations arising from the exercise of the right (i.e., transferring building ownership and, implicitly, vacating). Therefore, their action of objection to claim was fully upheld, preventing enforcement of the original eviction judgment.

The PDF commentary raises a hypothetical: if the tenants had exercised the purchase demand right but had remained in possession of the buildings (which, upon exercise of the right, legally became the landlord's property), their legal position would change. They would no longer have an obligation to remove the buildings (as the buildings now belong to the landlord), but they would acquire an obligation to vacate the landlord's newly owned buildings and surrender the land. The question then becomes whether this new duty to vacate the landlord's building and surrender the land is identical to, or a qualitative part of, the original "building removal and land surrender" duty. The Supreme Court's phrasing ("to that extent") is interpreted by the commentator as supporting a "partial extinguishment theory" (一部失効説 - ichibu shikkō setsu), meaning the original duty to remove the building is extinguished, but a duty to surrender the land (which may now include vacating the building that is no longer theirs) might persist or arise in a modified form.

Conclusion

The 1995 Supreme Court decision provides crucial protection for tenants in Japan by affirming that the statutory building purchase demand right is a robust protection that is not easily lost, even in the face of a final eviction judgment. By clarifying that this right is not precluded by the res judicata of a prior eviction judgment and can be exercised post-judgment to form a valid ground for an action of objection to claim, the Court reinforced the distinct nature and important socio-economic objectives of this tenant protection mechanism. This ruling ensures that the substantial investment tenants often make in buildings on leased land is not unduly forfeited due to a failure to exercise this right during the often contentious process of an eviction lawsuit.