Team Effort: How Japan's UCPA Protects Group Brand Identity – The Football Symbol Mark Case

Judgment Date: May 29, 1984

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: Showa 56 (O) No. 1166 (Main Claim for Injunction against Unfair Competition, etc.; Counterclaim for Damages)

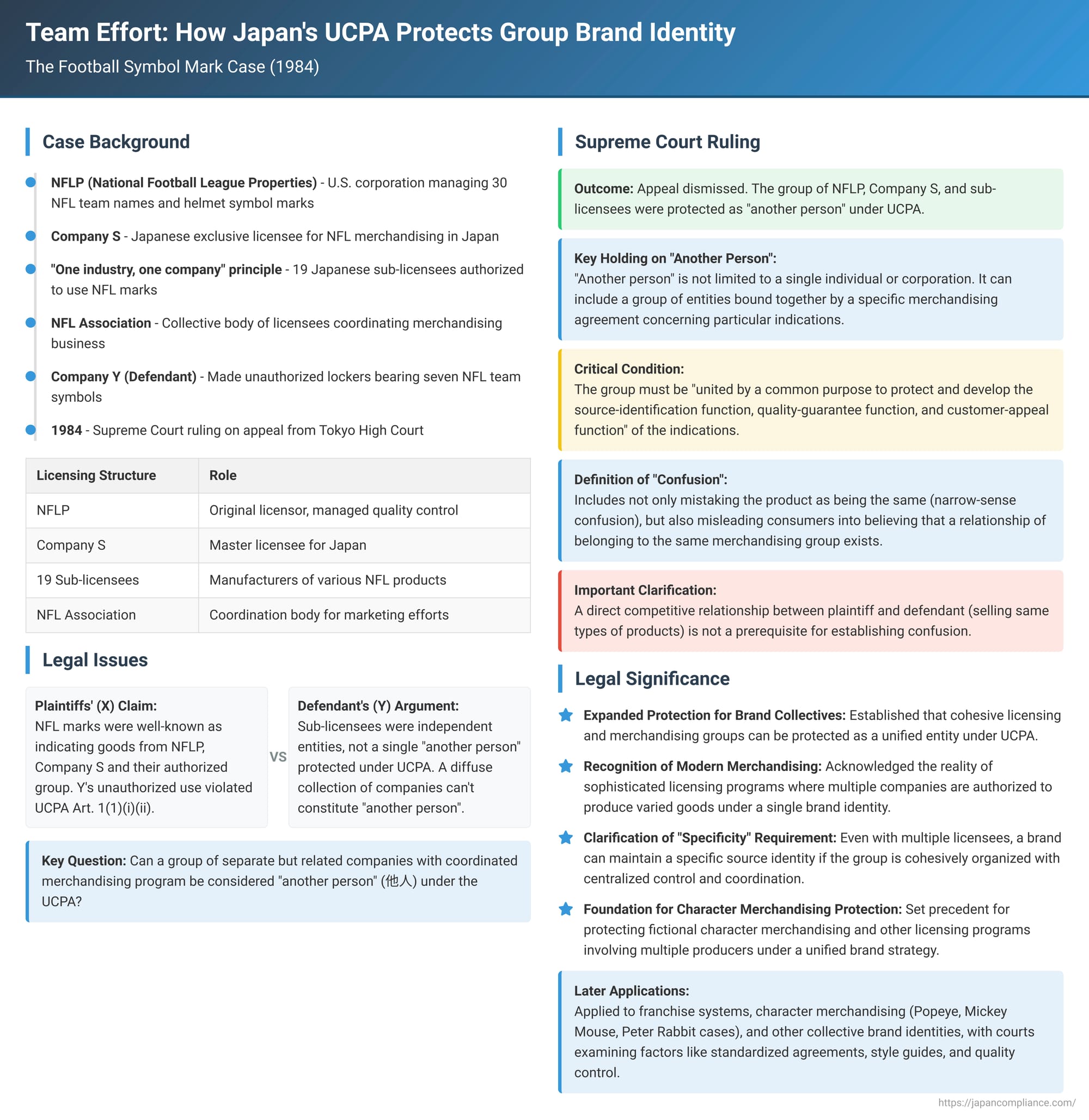

The "Football Symbol Mark Case," decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 1984, is a landmark judgment concerning the protection of brand identity under Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA). The case significantly clarified that the term "another person," whose well-known indications of source are protected against confusingly similar uses, can extend beyond a single corporate entity to encompass a collective group of businesses united by a common merchandising program. This decision broadened the scope of unfair competition protection, particularly for extensive licensing and character merchandising operations.

The NFL Comes to Japan: A Merchandising Program Takes Shape

The case involved the iconic symbols of the National Football League (NFL) teams.

- The Plaintiffs (X): The plaintiffs were NFLP (National Football League Properties, Inc.), a U.S. corporation responsible for managing the commercial use of the 30 NFL team names and their helmet-shaped symbol marks (collectively, "the Indications"), and Company S (at the time, Sony Kigyō Kabushiki Kaisha, a Japanese company). NFLP had granted Company S an exclusive license to develop and manage the merchandising business for these Indications in Japan.

- The Licensing Network: Company S, operating under a "one industry, one company" principle, selected and authorized 19 Japanese companies as sub-licensees (再使用権者 - sai shiyōkensha). These sub-licensees were permitted to manufacture and sell a variety of products (e.g., t-shirts, trainers, sweaters, socks, aprons, ties, shoes, watches, pennants, umbrellas, stationery) bearing the NFL Indications. Company S and these sub-licensees formed a collective body called the "NFL Association," which held monthly meetings to coordinate and exchange information regarding the merchandising business, advertising, and sales methods. There was a system of quality control and advertising guidelines imposed by NFLP and managed by Company S.

- The Defendant (Y) and the Alleged Unfair Competition: Company Y, the defendant, began manufacturing and selling assembled lockers. These lockers were covered in vinyl sheets printed with seven of the NFL team Indications. Company Y was not part of the official NFL merchandising program and had not received authorization from NFLP or Company S.

- The Lawsuit: NFLP and Company S (collectively "X") sued Company Y. They claimed that Y's activities constituted unfair competition under Japan's (then-effective) old Unfair Competition Prevention Act, Article 1, Paragraph 1, Item 1 (prohibiting the use of another's well-known product indication in a way that causes confusion) and Item 2 (prohibiting the use of another's well-known business indication in a way that causes confusion). These two provisions in the old UCPA correspond generally to Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the current UCPA. X argued that the NFL Indications had become well-known in Japan as signifying goods originating from, or the business of, X and their network of authorized sub-licensees, considered as a collective group.

- Y's Defense: Company Y countered that the sub-licensees were all independent business entities. It argued that such a diffuse collection of companies could not be considered "another person" (他人 - tanin) whose indications were protected under the UCPA. The implication was that if the source was not a single, identifiable entity, then there could be no specific source for consumers to be confused about.

Both the first instance court and the appellate court (Tokyo High Court) had ruled in favor of X, granting an injunction and damages. Company Y appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Broad View: Protecting Group Identity

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions. The judgment provided crucial interpretations of "another person" and "confusion" under the UCPA.

1. "Another Person" Can Be a Merchandising Group:

The Court held that the term "another person" as used in the UCPA (old Article 1(1)(i) and (ii)) is not limited to a single individual or a single corporate entity. It can include a group of entities, such as a licensor, a primary licensee, and their sub-licensees, who are bound together by a specific merchandising agreement concerning particular indications.

The key condition for such a collective to be recognized as "another person" is that the group can be evaluated as being "united by a common purpose to protect and develop the source-identification function, quality-guarantee function, and customer-appeal function" of the indications in question.

2. "Confusion" Includes Mistaken Affiliation with the Group:

The Supreme Court also clarified the scope of "acts causing confusion" (混同を生ぜしめる行為 - kondō o shōzeshimeru kōi):

- It includes acts where a party using an identical or similar indication misleads consumers into believing that their product or business is the same as that of the well-known "other person" (this is often termed "narrow-sense confusion").

- Significantly, it also encompasses acts that mislead consumers into believing that a relationship of belonging to the same merchandising group exists between the unauthorized user (the defendant) and the recognized "other person" (the plaintiff group). This addresses a broader form of potential consumer deception.

- The Court further stated that a direct competitive relationship between the plaintiff and the defendant (i.e., selling the same types of products) is not a prerequisite for establishing such confusion.

Application to the NFL Case Facts:

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found:

- The group consisting of X (NFLP and Company S) and their 19 authorized sub-licensees, bound by licensing agreements and the common purpose of the NFL merchandising program (including quality control and coordinated marketing efforts through the NFL Association), did qualify as "another person" under the UCPA.

- The NFL Indications had become well-known in Japan as indicating products or business activities associated with this specific group.

- Even though no member of X's official merchandising group was currently selling lockers (although one sub-licensee had been authorized to potentially do so in the future), Company Y's act of selling lockers bearing the genuine NFL Indications was likely to mislead consumers into believing that Company Y was part of, or affiliated with, this same official NFL merchandising group.

- Therefore, Company Y's actions constituted an act causing confusion with the product indications or business activities of "another person" (the NFLP/Company S/sub-licensee group) and violated the UCPA.

Unpacking "Specificity" and "Group Identity" under UCPA

This Supreme Court judgment is particularly important for its treatment of the "specificity" (特定性 - tokuteisei) requirement inherent in the UCPA's protection of well-known indications.

- The Need for a Recognizable Source: The UCPA requires that a protected indication must be well-known as indicating the goods or business of "another person." This implies that the indication must point to a specific, identifiable source in the minds of consumers. If an indication is used by so many disparate and unrelated entities that consumers no longer associate it with any particular origin or controlled group, then the use of a similar indication by yet another party might not cause the kind of source-based confusion that the UCPA aims to prevent. The Football Symbol Mark case directly addressed how this specificity can be maintained even when multiple parties are involved in using the indication.

- Prior Lower Court Approaches: Even before this Supreme Court decision, Japanese lower courts had shown a willingness to recognize a "group" as "another person." This was seen in cases involving:

- Indications well-known as identifying a group of affiliated companies (e.g., the Sekisui Development case; the Mitsubishi Construction case).

- Indications well-known as identifying a franchise system (e.g., the Hachiban Ramen case; the Sapporo Ramen Dosanko case; the Hokka Hoka Bento case; the ComputerLand Hokkaido case).

- However, where the use of an indication was too diffuse, protection could be denied. For example, in a case concerning "Kamen Rider" character dolls, the plaintiff (Poppy) was one of several companies (including its parent, Bandai) merchandising these dolls, alongside many other types of Kamen Rider products. A court found that, in this context, the Kamen Rider doll was not necessarily well-known as an indication of the plaintiff's specific goods as distinct from the general merchandising effort.

- Significance of the Supreme Court's Ruling: The Supreme Court's decision in the Football Symbol Mark case was significant because it authoritatively endorsed the concept of a "group" (specifically, "X and the sub-licensees' group") qualifying as "another person" under the UCPA, even within a complex merchandising scenario. The key was the existence of a cohesive structure with a common purpose, unified by licensing agreements and oversight mechanisms (like quality control and advertising coordination) managed by NFLP and Company S. If consumers recognize this "group" entity, even if they don't know all its individual members, and are misled into thinking an unauthorized product comes from or is approved by that group, then actionable confusion occurs.

Relationship with "Broad-Sense Confusion"

The Football Symbol Mark case is sometimes described as a judgment that recognized "broad-sense confusion" (広義の混同 - kōgi no kondō). However, the PDF commentary offers a more nuanced interpretation:

- Typical "broad-sense confusion" usually refers to situations where consumers recognize the defendant as a separate entity from the plaintiff but are misled into thinking there is some kind of business affiliation, sponsorship, or other connection between them (as seen in cases like Nippon Woman Power or Snack Chanel).

- The Football Symbol Mark case, arguably, operated slightly differently. It primarily expanded the definition of the "source" or "another person" to encompass the entire organized merchandising group. The confusion found was then that consumers mistakenly believed the defendant (Company Y) was part of this recognized group. In this sense, once the "group" is established as the relevant "another person," the confusion could be seen as a form of "narrow-sense confusion" relative to that group identity.

- For this judgment's logic to apply, there needs to be a demonstrable "group" or cohesive entity identifiable by the indication. It doesn't automatically extend to any vague consumer assumption that there might be a licensing relationship in general. The PDF commentary views this requirement for a "group" with actual cohesion as a positive and necessary limit, preventing an over-extension of liability based merely on a mistaken belief about a licensing tie-up where no unified source identity exists.

Subsequent Developments in Merchandising and Character Rights Cases

After the Football Symbol Mark decision, courts continued to grapple with the "specificity" requirement, especially in the context of character goods where multiple licensees might be involved:

- Some cases followed a similar line, looking for evidence of controlled licensing, such as "one industry, one company" policies (e.g., further "Popeye" cases).

- Other decisions appeared more lenient, recognizing the licensor or the "headquarters" of a merchandising operation as the relevant "another person" without exhaustive proof of strict control over all sub-licensees (e.g., a "Mickey Mouse character" case).

- The "Peter Rabbit" case considered factors like the existence of standardized merchandising agreements (covering design approval, IP management, sublicensing prohibitions, sales method constraints) and the use of style guides to maintain a consistent brand image when finding a protectable group indication. However, the commentary cautions that such elements could become somewhat formulaic if not substantively implemented.

There are, of course, limits. Protection has been denied where:

- Licensees of a utility model for rice seedling bags prominently used their own individual company names and trademarks on the products, preventing consumers from perceiving a unified group source, even if the underlying technology was licensed from the plaintiff.

- A plaintiff acting as an OEM manufacturer for various companies that then sell the products under their own distinct brands cannot easily claim that the underlying product form is a well-known indication of the plaintiff's business or a unified group source. Consumers must perceive the manufacturer or a cohesive manufacturing group as the source.

- In a dispute over the martial art name "Nippon Kempo," where multiple independent organizations used the name, had a history of some loose affiliation but had later diverged (e.g., issuing their own separate certifications), the court found they did not constitute a sufficiently "tightly-knit group" for UCPA protection of the name as indicating a single collective entity.

Conclusion

The Football Symbol Mark Supreme Court decision marked a crucial development in Japanese unfair competition law. It established that a well-organized and centrally controlled merchandising group, united by a common purpose in developing and protecting the goodwill of specific indications (like sports team logos or character images), can be recognized as "another person" whose well-known indications are protected from unauthorized uses that are likely to cause consumer confusion. This confusion includes misleading the public into believing that an unauthorized party is affiliated with, or part of, such a recognized group. The ruling provided vital support for brand owners and licensors engaged in extensive merchandising programs by acknowledging the collective nature of the goodwill they cultivate and by offering a legal pathway to protect that group identity against free-riding and deceptive affiliations in the marketplace. It underscores the UCPA's adaptability to evolving commercial practices, particularly in the realm of character and brand licensing.