Taxpayer Negligence vs. Agent Fraud: Japanese Supreme Court on "Justifiable Grounds" for Tax Penalties

Date of Judgment: April 20, 2006

Case Name: Income Tax Reassessment Disposition, etc. Invalidation, and State Compensation Claim Case (平成17年(行ヒ)第9号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

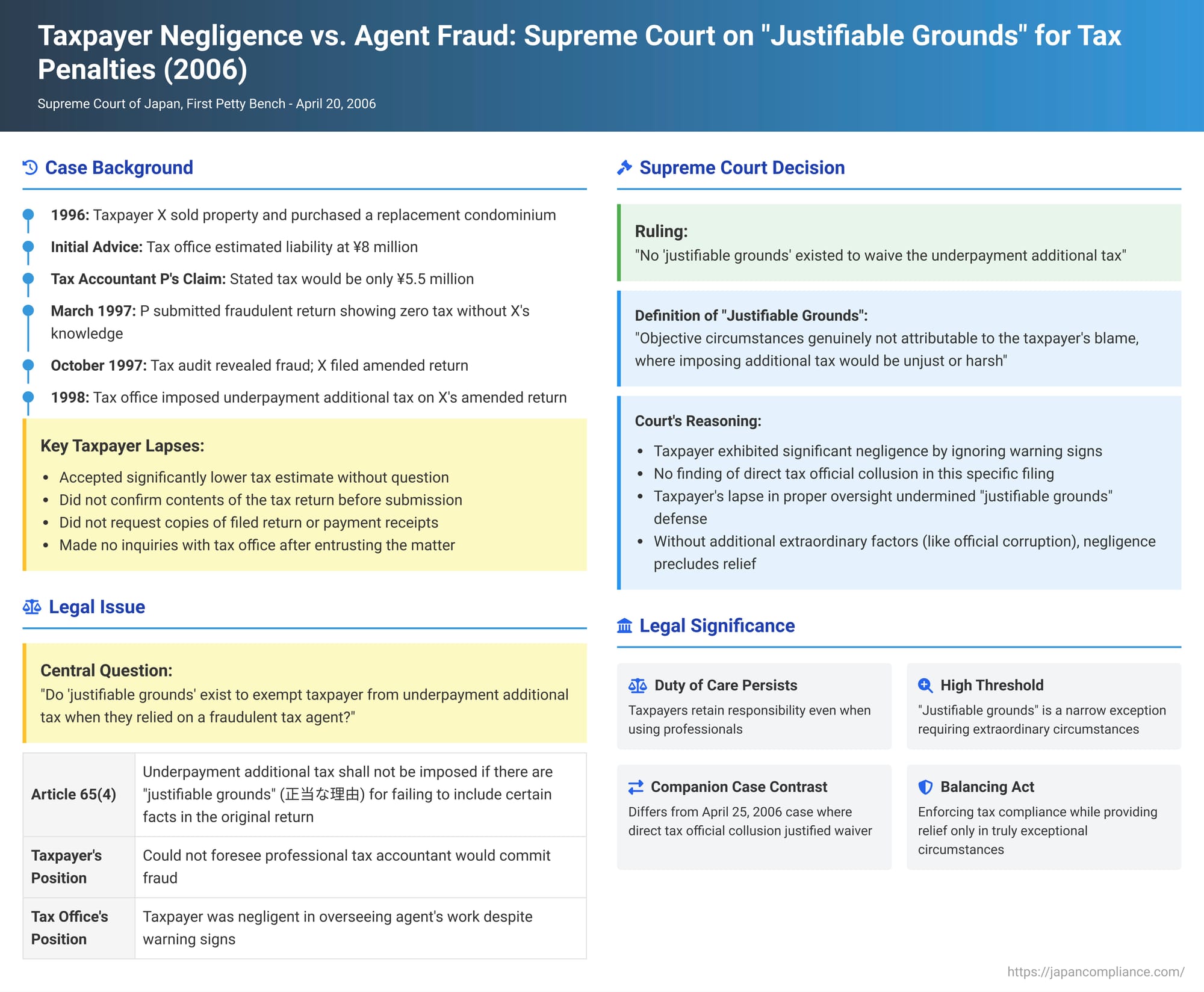

In a judgment delivered on April 20, 2006, which forms a companion to another significant ruling involving the same fraudulent tax accountant (see case t100.pdf, decided April 25, 2006), the Supreme Court of Japan delved into the conditions under which a taxpayer might be excused from underpayment additional tax due to "justifiable grounds." This case specifically examined a situation where a taxpayer relied on a tax agent who committed fraud, but where direct collusion by tax officials in that specific taxpayer's fraudulent filing was not established by the Supreme Court as a decisive factor for waiving this particular penalty. The Court's decision underscores the taxpayer's residual duty of care, even when employing a professional agent.

The Deceived Taxpayer: A Story of Misplaced Trust

The taxpayer, X (born in 1920), had sold her residential property in Nerima Ward, Tokyo, in 1996 and subsequently purchased a replacement condominium in Ota Ward, moving her residence. X entrusted the complex income tax filing procedures related to this property sale and replacement to her husband, A.

Seeking guidance, A consulted the Yukigaya Tax Office, where an official informed him that the estimated tax liability (national and local combined) would be around ¥8 million. X's son, B, also provided a similar estimate. However, as A was unfamiliar with the calculation methods and the preparation of the tax return forms, he, along with B's wife, decided to consult P, a tax accountant who handled the tax affairs for B's wife's mother.

During the consultation, P was shown a memo prepared by B indicating the likely tax amount of ¥8.04 million. P initially commented, "That's about right," but then, while making his own notes, stated, "The tax will probably come to ¥5.5 million. Plus, give my assistant ¥100,000 as a fee, so ¥5.6 million in total." When A inquired how the tax could be so much lower, P evasively replied, "I worked at the tax office for a long time, so my calculations are different from an amateur's. I can calculate it properly, so there's no mistake." A did not press further. Trusting P's expertise, A and his family decided to engage P for the tax filing, informed X, and handed over ¥5.6 million to P (¥5.5 million for the purported tax and ¥100,000 for the fee).

The judgment notes that X and A entrusted P with the filing in good faith, believing he was a professional who would handle the procedures correctly, and they had no intention of evading taxes. They were also unaware of P's extensive history of engaging in tax fraud, often involving bribery of tax officials, for which P was later arrested in October 1997 and subsequently convicted and imprisoned.

P, however, proceeded to commit fraud. He falsely notified the tax authorities that X had moved her residence to the jurisdiction of the Nerima East Tax Office. Then, on March 5, 1997, P, purportedly acting as X's agent, submitted a fraudulent income tax return for X's 1996 income to a supervising national tax investigator at the Nerima East Tax Office. This return falsely declared X's capital gains from the property sale and her tax due as ¥0. This was achieved by P submitting a fabricated "Inquiry Sheet on Details of Transfer" (譲渡内容についてのお尋ね - jōto naiyō ni tsuite no o-tazune bunsho) which falsely stated that the property sold had been acquired in 1990 for ¥106 million (thereby creating a fictitious high acquisition cost to eliminate any taxable gain). The tax investigator at Nerima East accepted the return, stamped it, and provided P with a copy. While the investigator noted in internal records that a consultation with P had occurred, he merely transcribed the false acquisition cost from P's inquiry sheet without attempting to verify it against supporting documents. The judgment indicates that the fraudulent nature of the filing was not immediately obvious from the face of the tax return itself, and the Nerima East investigator's actions in this specific instance were not found by the Supreme Court majority to constitute active collusion in X's particular fraudulent filing. P never showed the contents of the fraudulent return to X or A, nor did he obtain X's signature or seal on it, and he kept the ¥5.5 million provided by X for tax payment for himself.

Following the uncovering of P's broader fraudulent activities, the Tokyo Regional Tax Bureau commenced an audit of X in October 1997. X subsequently filed an amended income tax return ("the subject amended return") with Y (the Yukigaya Tax Office Head), properly claiming the special tax provisions for the replacement of residential property and submitting the necessary supporting documents. This amended return showed an additional tax liability of approximately ¥5.5 million.

The tax office (Y) then issued several dispositions against X:

- First Imposition Decision: Heavy additional tax was imposed on the ¥5.5 million tax liability arising from X's amended return.

- Second Imposition Decision (Reassessment): Y subsequently issued a corrective assessment ("the subject reassessment") which denied X's eligibility for the special tax provisions claimed in her amended return. This led to a further increase in her main tax liability, and heavy additional tax was imposed on this additional amount as well.

X initiated a lawsuit challenging these dispositions. The case wound its way through the lower courts with various outcomes on different points. The Supreme Court ultimately accepted an appeal from the tax office (Y) concerning the High Court's decision to waive the underpayment additional tax portion related to the First Imposition Decision (i.e., the penalty on the tax X self-assessed in her amended return). The Supreme Court had, in this same judgment, already dismissed Y's appeal regarding the heavy additional tax portion of the First Imposition Decision, effectively agreeing with the lower courts that heavy additional tax was not applicable to X for P's fraud because X did not meet the criteria for such attribution (this part of the judgment mirrors the reasoning in the companion case, t100.pdf). Thus, the specific focus of the Supreme Court's reasoning detailed in this particular judgment extract pertains to whether "justifiable grounds" existed to waive the standard underpayment additional tax.

The Legal Question: When are "Justifiable Grounds" Present for Waiving Underpayment Additional Tax?

The primary legal question addressed by this specific Supreme Court judgment was: Did "justifiable grounds" (正当な理由 - seitō na riyū), as stipulated in Article 65, paragraph 4 of the General Act of National Taxes, exist to exempt taxpayer X from the standard underpayment additional tax that arose from her amended tax return? This return corrected the initial zero-tax filing fraudulently made by her tax agent, P. The key was whether X's reliance on this deceitful agent, coupled with her own lack of diligence in verifying the information provided by P, constituted "justifiable grounds," particularly in a scenario where the Supreme Court majority did not find active, direct collusion by tax officials in relation to X's specific fraudulent filing.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Negligence Undermines "Justifiable Grounds" Absent Official Collusion in Taxpayer's Specific Filing

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision on this point and upheld the tax office's original imposition of the standard underpayment additional tax on X relating to her amended return. The Court found that "justifiable grounds" did not exist to waive this penalty.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Nature and Purpose of Underpayment Additional Tax:

- The Court began by defining underpayment additional tax. It is imposed, in principle, whenever an under-declaration of tax occurs.

- Its objectives are: (a) to redress the objective unfairness between taxpayers who file correctly and pay their taxes on time, and those who under-declare; and (b) to prevent such under-declarations, promote the proper functioning of the self-assessment system, and thereby secure the collection of tax revenue.

- It contains fewer punitive elements (related to subjective culpability or intent) compared to the more severe heavy additional tax.

- Meaning of "Justifiable Grounds" (Article 65, paragraph 4 of the General Act):

- Article 65, paragraph 4 provides that underpayment additional tax shall not be imposed on the portion of the tax liability arising from an amended return or reassessment if, concerning the facts that formed the basis for the additional tax, there are "justifiable grounds" for those facts not having been included in the calculation for the original tax return.

- The Supreme Court, in this judgment, provided a general definition for "justifiable grounds": this refers to situations where there are "objective circumstances genuinely not attributable to the taxpayer's blame" (真に納税者の責めに帰することのできない客観的な事情 - shin ni nōzeisha no seme ni kisu koto no dekinai kyakkanteki na jijō), AND where, even considering the aforementioned purpose of the underpayment additional tax, imposing such additional tax on the taxpayer would still be "unjust or harsh" (futō mata wa koku). This was noted by legal commentators as the Supreme Court's first general articulation of this standard.

- Application to Taxpayer X's Case:

- The Court acknowledged that X might not have been able to foresee that P, a qualified tax accountant, would engage in such fraudulent acts.

- However, the Court pointed to several "lapses" (ochido) or instances of negligence on X's part (acting through her husband A):

- X was informed by tax officials and her son that the expected tax amount was around ¥8 million. Despite this, she (via A) accepted P's significantly lower figure of ¥5.5 million without further investigation or seeking a clear explanation for the discrepancy.

- X did not confirm the contents of the tax return filed by P before its submission.

- X did not subsequently request a copy of the filed return or any receipts for tax payment from P.

- X did not make any inquiries with the tax office regarding the status of her tax filing or payment after entrusting the matter to P.

- Absence of Tax Official Collusion in X's Specific Filing: Crucially, the Court stated: "on the other hand, the fact that the tax office official who accepted the subject tax return colluded in the tax evasion act by the said tax accountant is not found". While the investigator at Nerima East was negligent in his duties by not properly verifying the information P submitted for X, the Supreme Court majority in this specific judgment concerning X did not characterize this as the same kind of active, direct collusion in X's particular fraudulent filing that was found in the companion case (t100.pdf), which involved a different taxpayer also defrauded by P but where a tax official was bribed to specifically overlook that taxpayer's fraudulent return.

- Conclusion on "Justifiable Grounds" for X: Given X's own lapses and the absence of a finding by the SC of active tax official collusion directly facilitating her specific fraudulent filing, the Court concluded that X's situation did not meet the high threshold of "objective circumstances genuinely not attributable to the taxpayer's blame" where imposing the underpayment additional tax would be "unjust or harsh."

- Therefore, "justifiable grounds" under Article 65, paragraph 4 did not exist to exempt X from the underpayment additional tax on the amount she declared in her amended return. The High Court's decision to waive this penalty was thus overturned.

Analysis and Implications

This judgment, especially when read in conjunction with its companion case (t100.pdf, where "justifiable grounds" were found for a different taxpayer due to direct tax official collusion), provides important distinctions regarding taxpayer responsibility and penalties:

- Taxpayer's Duty of Care Persists When Using Agents: The ruling underscores that while taxpayers are entitled to delegate complex tax matters to professionals like tax accountants, they are not entirely absolved of a basic duty of care. Ignoring significant "red flags" (such as a tax liability drastically lower than previously advised by other credible sources) or failing to make reasonable inquiries or checks concerning the agent's work can be construed as negligence.

- High Threshold for "Justifiable Grounds": The Supreme Court's definition and its application in this case indicate that "justifiable grounds" for waiving underpayment additional tax is a narrow exception. It generally requires circumstances that are truly beyond the taxpayer's reasonable ability to control or foresee, and where the imposition of the penalty would be genuinely unfair or excessively severe in light of the penalty's purpose. Mere reliance on a tax agent, even one who proves to be fraudulent, is not, by itself, sufficient if the taxpayer also exhibited negligence.

- The Critical Impact of Direct Official Misconduct: Comparing this outcome with the companion case (t100.pdf), the presence or absence of active, direct collusion by tax officials in the specific taxpayer's fraudulent filing appears to be a decisive factor. In the companion case, where direct bribery and complicity of a tax official in that taxpayer's fraudulent under-declaration were established, the Supreme Court found "extremely special circumstances" that constituted "justifiable grounds" for waiving the underpayment additional tax, even though that taxpayer also had some lapses. In the present case concerning X, the Supreme Court majority did not find such direct, active collusion by tax officials in her specific filing (distinguishing general negligence by an official from active, conspiratorial involvement in a specific taxpayer's case) that would override her own negligence.

- Balancing Tax Enforcement with Equity: The decision reflects the judiciary's ongoing effort to balance the need for effective tax enforcement (where penalties for underpayment serve as a deterrent and ensure fairness to compliant taxpayers) with the imperative to provide relief in truly exceptional situations where penalizing the taxpayer would be profoundly unjust. Taxpayer negligence generally weighs against such relief, unless counterbalanced by more egregious factors such as direct misconduct by the state's own agents in relation to that taxpayer's specific filing.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's April 20, 2006, decision clarifies that a taxpayer's negligence in overseeing the work of their tax agent, particularly in the face of information that should have prompted further inquiry, will generally preclude a finding of "justifiable grounds" for waiving underpayment additional tax, even if the agent ultimately committed fraud. This ruling highlights the limited scope of the "justifiable grounds" defense and emphasizes that taxpayers retain a degree of responsibility for the accuracy of their tax declarations, even when professional assistance is sought. The case also implicitly underscores, by its contrast with its companion ruling, that direct and active collusion by tax officials in a taxpayer's specific fraudulent filing can create the "extremely special circumstances" necessary to find that imposing even standard penalties would be unjust.