Taxman's Knock: Japanese Supreme Court on the Scope of Tax Investigation Powers

Date of Decision: July 10, 1973

Case Name: Income Tax Act Violation Case (昭和45年(あ)第2339号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

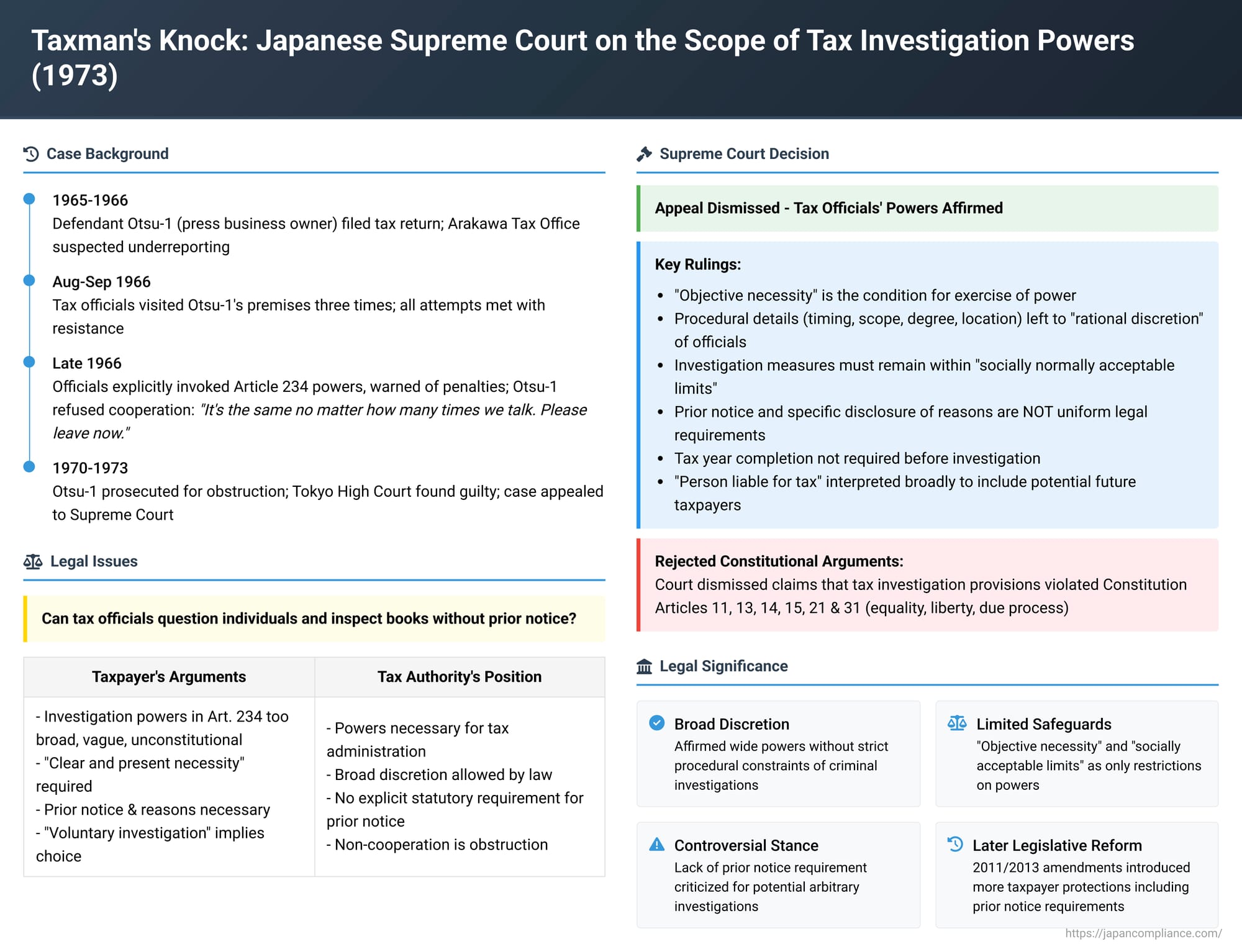

In a significant decision issued on July 10, 1973, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the scope and limitations of the tax authorities' powers to question individuals and inspect their books and records. The case arose from a criminal prosecution for violation of the Income Tax Act, where the defendant, a business owner, had resisted tax officials' attempts to conduct an audit. The Supreme Court ultimately affirmed the broad discretionary powers of tax officials in conducting such investigations under the then-prevailing Income Tax Act (Law No. 27 of 1947, prior to revisions that later transferred many procedural rules to the General Act of National Taxes).

The Standoff: Taxpayer Resistance Meets Official Inquiry

The defendant, referred to as 《乙1》 (Otsu-1), was an individual engaged in a press working business. After Otsu-1 filed an income tax return for the 1965 tax year and paid the declared tax, the Arakawa Tax Office suspected underreporting and deemed a further investigation necessary.

Between August and September 1966, tax officials from the Arakawa Tax Office visited Otsu-1's premises on three separate occasions. However, each attempt to conduct an audit ended in confrontation, and the officials were unable to achieve their investigative objectives.

A few days after the third unsuccessful visit, two tax officials went to Otsu-1's premises again. This time, they explicitly informed Otsu-1 of their authority to conduct questioning and inspection under Article 234 of the Income Tax Act (a provision later largely incorporated into Article 74-2 of the General Act of National Taxes). They also warned Otsu-1 that non-cooperation with such an investigation was a punishable offense. The officials then requested to see Otsu-1's books and documents, asked for the names and addresses of clients and suppliers, and requested permission to inspect the factory premises. Otsu-1 refused these requests, reportedly stating, "It's the same no matter how many times we talk. Please leave now."

As a result of this resistance, Otsu-1 was prosecuted for violating the Income Tax Act, presumably for obstructing a tax investigation. The Tokyo High Court, in a judgment on October 29, 1970, appears to have found Otsu-1 guilty. Otsu-1 then appealed to the Supreme Court, raising numerous constitutional and statutory challenges to the legality of the investigation itself and the interpretation of the tax officials' powers.

Otsu-1's arguments before the Supreme Court included contentions that:

- The legal provisions granting questioning and inspection powers (Article 234(1) and the penalty provision, Article 242(8), of the old Income Tax Act) were unconstitutional (allegedly violating Articles 11, 13, 14, 15, 21, and 31 of the Constitution) because they were overly broad, vague, susceptible to abuse, and imposed unreasonably severe penalties for any form of non-cooperation.

- Tax officials should not be permitted to use questioning and inspection powers if alternative means of investigation were available.

- The exercise of such powers requires a "clear and present necessity," and in this instance, the officials allegedly attempted to conduct the investigation without such urgent need, without prior notice, and without clearly stating the reasons for and scope of the investigation. Otsu-1 argued that a lawful investigation had not even properly commenced.

- The term "said officials" (当該職員 - tōgai shokuin) in the law, who are authorized to conduct investigations, lacked a clear statutory definition of their scope of authority, rendering the provision an unconstitutional "blank criminal law" (allowing administrative discretion to define the crime).

- It was irrational and unconstitutional to penalize refusal to cooperate with an investigation when such investigations are often referred to as "voluntary investigations" (任意調査 - nin'i chōsa), implying the taxpayer has a choice.

- There were various other procedural irregularities and constitutional violations in the lower court proceedings.

The Legal Battleground: The Reach of Tax Investigation Powers

The case centered on the interpretation of Article 234, paragraph 1 of the old Income Tax Act. This article empowered officials of the National Tax Agency, Regional Tax Bureaus, or Tax Offices, when deemed necessary for an investigation concerning income tax, to:

- Question individuals liable for tax, or deemed liable for tax, or individuals obligated to withhold tax at source.

- Inspect books, documents, and other items related to the business of such persons.

The core legal questions revolved around the extent of discretion granted to tax officials in exercising these powers and the procedural safeguards, if any, afforded to taxpayers.

The Supreme Court's Interpretation: Broad Discretion within Limits

The Supreme Court dismissed all of Otsu-1's appeals, finding that his arguments did not constitute valid grounds for appeal under Article 405 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (which outlines permissible reasons for final appeal). However, in point "一〇" (Ten) of its reasoning, the Court provided its definitive interpretation of the scope and nature of the questioning and inspection powers under the old Income Tax Act Article 234, paragraph 1.

The Supreme Court's key interpretive points were:

- General Authority for Ex Officio Investigation: The Court began by noting that the process of assessing and collecting income tax involves various administrative actions by tax authorities (such as making corrective assessments, deciding on applications for estimated tax reductions or blue form return approvals, processing loss carryback refund claims, approving deferred tax payments, or ordering pre-emptive asset seizures). These actions often require fact-finding and judgment by the tax authorities. The law, therefore, inherently permits ex officio (on their own initiative) investigations by tax authorities within the scope necessary for these official duties.

- Questioning and Inspection as an Investigative Method: Article 234, paragraph 1, the Court stated, grants officials possessing investigative authority (from the National Tax Agency, Regional Tax Bureaus, or local Tax Offices) the power to question specified persons or inspect their business-related books, documents, and other relevant items as one method of conducting such ex officio investigations.

- Condition for Exercise of Power – "Objective Necessity": This power can be exercised when, after considering all concrete circumstances—including the purpose of the investigation, the specific matters to be investigated, the form and content of any applications or declarations made, the state of the taxpayer's books and record-keeping, the nature of the taxpayer's business, etc.—it is judged by the tax officials that there is an "objective necessity" (客観的な必要性 - kyakkanteki na hitsuyōsei) for such questioning or inspection.

- Discretion Regarding Procedural Details: The Court held that the specific details of how an investigation is implemented—such as its scope, degree, timing, and location—where not explicitly prescribed by statute, are generally left to the "rational discretion (or choice)" (合理的な選択 - gōriteki na sentaku) of the authorized tax officials. This discretion is, however, subject to two overarching conditions:

- There must be a necessity for the questioning and inspection.

- The measures taken must remain within limits that are considered "socially normally acceptable" (社会通念上相当な限度 - shakai tsūnenjō sōtō na gendo) when balancing this necessity against the private interests of the person being investigated.

- Timing of Investigation – No Prohibition Before Year-End or Filing Deadline: The Supreme Court clarified that tax investigations are not legally prohibited even if conducted before the end of the calendar year (for individual income tax) or before the tax filing period has expired. This is because the various official duties of tax authorities often require investigations to be conducted prior to these cut-off dates.

- Prior Notice and Specific Disclosure of Reasons/Necessity – Not Uniform Legal Requirements: Crucially, the Court stated that advance notice of the date, time, and place of an investigation, or an individual and specific disclosure of the reasons and necessity for the investigation, are NOT uniform legal requirements that must be met in every instance before questioning or inspection can be lawfully conducted under Article 234(1).

- Broad Definition of "Person Liable for Tax" Subject to Investigation: The Court interpreted the terms "person liable for tax" (納税義務がある者 - nōzei gimu ga aru mono) and "person deemed liable for tax" (納税義務があると認められる者 - nōzei gimu ga aru to mitomerareru mono) broadly. Considering the overall aim of the Income Tax Act to ensure fair and equitable taxation, and noting that Article 5 of the Act broadly defines those "who have a duty to pay income tax" to include persons who will eventually bear tax liability if taxable events occur in the future, the Court held that:

- "Person liable for tax" under Article 234(1) includes not only those whose tax liability has already objectively arisen because statutory tax requirements have been fulfilled and whose tax has not yet been finally and correctly paid, but also those for whom the tax year has commenced and income (which will form the basis of taxation) has started to accrue, such that they are expected to ultimately bear tax liability in the future.

- "Person deemed liable for tax" refers to a person who, in the rational judgment of the authorized tax official, is reasonably presumed to fall under the above broad definition of a person liable for tax.

Based on this comprehensive interpretation, the Supreme Court found no merit in Otsu-1's arguments challenging the legality or constitutionality of the tax officials' actions or the underlying legal provisions, and his appeal was dismissed.

Analysis and Implications

The Supreme Court's 1973 decision significantly shaped the understanding of tax investigation powers in Japan at the time:

- Affirmation of Broad Investigative Powers: The ruling strongly affirmed the broad discretionary powers of Japanese tax authorities to initiate and conduct investigations, including questioning and inspection of records. These powers were not seen as being constrained by the same strict procedural requirements (such as judicial warrants) that apply to criminal investigations.

- "Objective Necessity" and "Socially Acceptable Limits" as Guiding Principles: While granting wide discretion, the Court did articulate limits based on "objective necessity" for the investigation and the requirement that the methods used remain within "socially normally acceptable limits" when balanced against individual rights. This introduces a form of proportionality test, albeit one that still leaves considerable leeway to the authorities.

- Controversy over Lack of Mandatory Prior Notice and Detailed Reasons: The Supreme Court's explicit stance that advance notice and specific disclosure of reasons for an investigation are not always legally required was, and continued to be, a point of significant debate and concern among legal scholars and practitioners regarding taxpayer rights, procedural fairness, and the potential for abuse of power. Critics argued that such procedural safeguards are essential to protect taxpayers from arbitrary or overly intrusive investigations.

- Subsequent Legislative Changes – A Shift Towards Greater Taxpayer Protection: It is critically important to contextualize this 1973 ruling with subsequent legislative developments. As noted by legal commentators, significant amendments to the General Act of National Taxes in 2011 (which came into effect in 2013) introduced more formalized procedures for tax audits. These reforms, in many typical audit situations, do now require tax authorities to provide taxpayers with prior notification of an audit, including information about the purpose, scope, date, and place of the investigation, unless specific exceptions apply (e.g., if prior notice might impede the investigation). Therefore, while this Supreme Court decision remains a landmark statement on the inherent scope of tax investigation powers under the legal framework of its time, current tax audit practice in Japan is now significantly more governed by these newer, more taxpayer-protective procedural rules in many common scenarios.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1973 decision in this income tax violation case provided a foundational interpretation of the tax authorities' powers of questioning and inspection under the then-existing Income Tax Act. It underscored the broad discretion vested in tax officials to conduct investigations deemed objectively necessary for the fair and equitable administration of the tax system, while also acknowledging that such powers must be exercised within socially acceptable limits. The ruling's position that prior notice and detailed disclosure of reasons were not universally mandated legal prerequisites for investigations highlighted a tension with procedural fairness concerns for taxpayers. This tension was later addressed, to a significant extent, by legislative reforms that introduced more robust procedural safeguards for taxpayers in the context of tax audits. Nonetheless, this 1973 judgment remains a key historical reference point for understanding the legal underpinnings of tax investigative authority in Japan.