Taxing the Uncollectible? The Japanese Supreme Court on Interest Exceeding Legal Limits

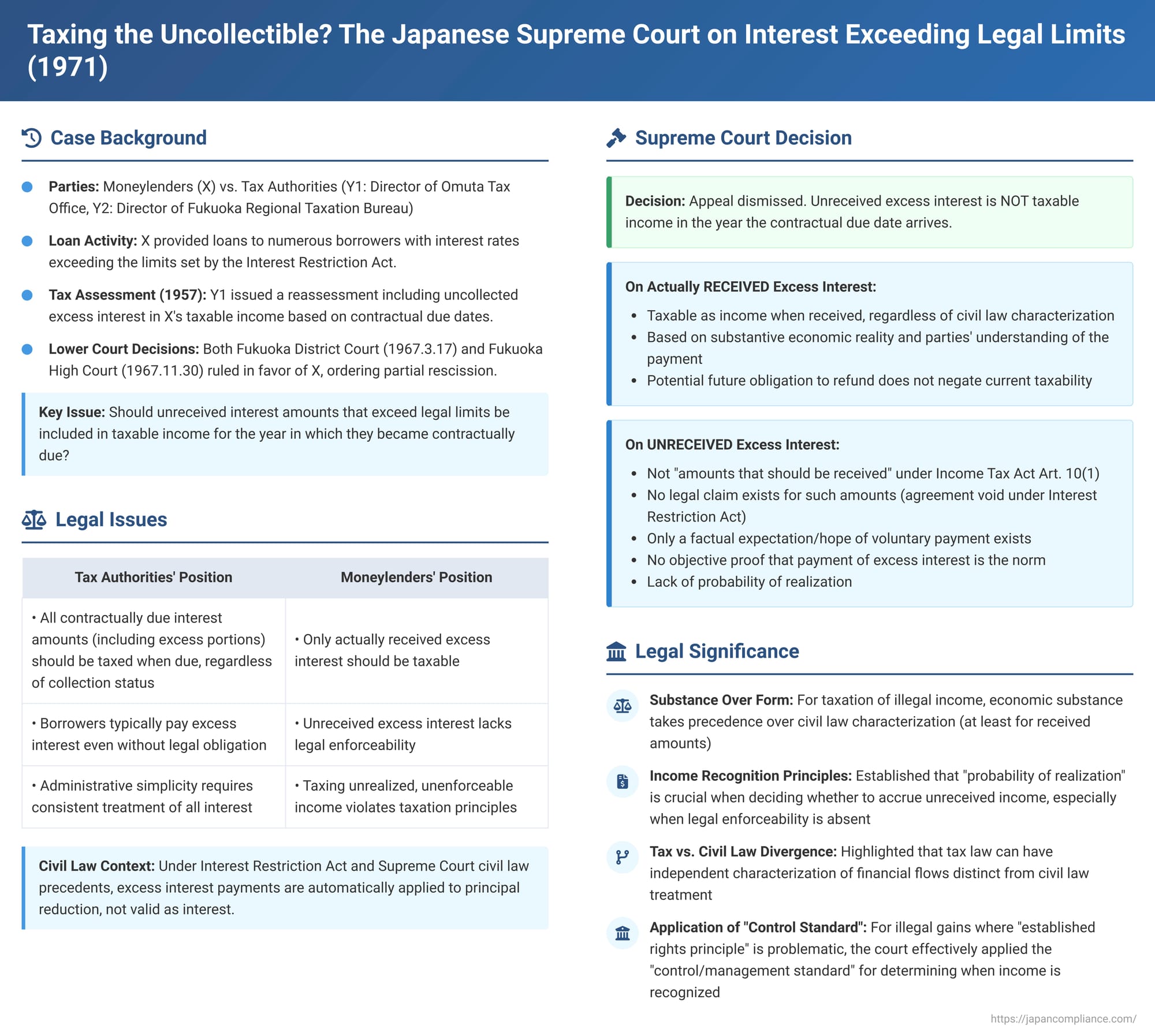

Case: Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of November 9, 1971 (Showa 43 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 25: Action for Rescission of Administrative Review Decision and Income Tax Reassessment Decision, etc.)

Introduction

On November 9, 1971, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment concerning the taxation of income derived from activities that contravene statutory provisions, specifically, interest charged by moneylenders that exceeded the limits stipulated by Japan's Interest Restriction Act (利息制限法, Risoku Seigenhō). This case delved into the fundamental principles of income recognition under Japanese tax law, drawing a crucial distinction between interest payments actually received by the lenders and those that had merely become due but remained uncollected. The Court’s decision provides enduring insights into how the Japanese tax system approaches illegal income and the criteria for determining when income is deemed "realized" for tax purposes, particularly when legal enforceability is absent.

The central issue was whether moneylenders, X, were liable for income tax on interest amounts that surpassed the legal cap, especially for portions that were contractually due in 1957 but had not yet been paid. The tax authorities, Y1 (Director of the Omuta Tax Office) and Y2 (Director of the Fukuoka Regional Taxation Bureau), argued for their inclusion in taxable income, while X contended otherwise for the unreceived amounts.

Facts of the Case

The appellees, X, were individuals engaged in the business of moneylending. They had provided loans to numerous borrowers at interest rates that exceeded the maximum permissible rates set forth by the Interest Restriction Act. For X's income tax assessment for the year 1957, Y1, the Director of the competent tax office, issued a reassessment disposition. This reassessment included in X's gross revenue (総収入金額, sōshūnyū kingaku) amounts of interest exceeding the statutory limits (hereinafter "excess interest") for which the contractual due date had arrived within that year, even if these amounts had not yet been actually collected by X.

X, disagreeing with this treatment of uncollected excess interest, went through the appropriate administrative appeal procedures. Subsequently, they filed a lawsuit against Y1 and Y2 (who had made the administrative review decision) seeking the rescission of the tax authorities' decisions.

The Fukuoka District Court, as the court of first instance (judgment of March 17, 1967), ruled in favor of X, ordering a partial rescission of the reassessment. This decision was upheld by the Fukuoka High Court (judgment of November 30, 1967). Dissatisfied with these outcomes, Y1 and Y2 appealed to the Supreme Court. The primary point of contention before the Supreme Court was the taxability of the unreceived portion of the excess interest.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal lodged by the tax authorities, Y1 and Y2. The Court meticulously distinguished between the tax treatment of excess interest that had been actually received and that which remained unreceived.

Reasoning Regarding Actually Received Excess Interest

The Court first considered the scenario where excess interest had been actually received by the lenders:

- Civil Law Status: The Court acknowledged its own established precedent in civil law (Supreme Court Grand Bench judgment, November 18, 1964). According to this precedent, even if a borrower pays interest or damages exceeding the limits of the Interest Restriction Act, such payment does not have legal effect as a valid interest payment. Instead, the excess portion is, by operation of law (referring to Article 491 of the Civil Code, pre-2017 amendment, now corresponding to Article 489), applied towards the repayment of the remaining principal amount of the loan. This civil law interpretation, the Court noted, might make it seem that the excess portion is merely a recovery of principal and therefore does not constitute income.

- Tax Law Principle: However, the Supreme Court emphasized a fundamental principle of tax law: whether something constitutes taxable income is not necessarily determined solely by its legal nature or characterization under private law.

- Substantive Treatment by Parties: The Court reasoned that if the parties involved (lender and borrower) exchange funds with the understanding that they are for agreed-upon interest and damages, and if the lender, without treating the excess portion as a repayment of principal, continues to consider the original principal amount as still outstanding, then the entire amount of the agreed interest and damages actually received – including the portion exceeding the statutory limit – should be considered taxable income for the lender.

- Potential for Future Refund Claims: The Court also addressed the possibility that a borrower might continue making payments of agreed interest and damages, and if the excess portions, when applied to the principal, lead to a situation where the principal is calculated as fully repaid, the borrower could then legally claim the return of subsequent payments as unjust enrichment (as per Supreme Court Grand Bench judgment, November 13, 1968). This means a lender might receive excess interest but could, under law, be unable to retain it. However, the Court held that this potential future obligation to refund does not, in itself, mean that the excess portion actually received cannot be considered taxable income at the time of receipt.

Reasoning Regarding Unreceived Excess Interest

The Court then turned to the core issue of the appeal: the taxability of excess interest that had accrued but was not yet received:

- General Principle for Legal Interest: For ordinary interest and damages on a loan that are within legal limits, the Court stated that once the due date for payment arrives, such amounts are generally considered "amounts that should be received" (収入すべき金額, shūnyū subeki kingaku) under Article 10, Paragraph 1 of the Old Income Tax Act (Law No. 27 of 1947, prior to the 1965 amendment). As such, they constitute taxable income even if they remain uncollected at that point. This is because, in the absence of special circumstances, there is a high probability of their eventual realization and collection.

- Status of Excess Interest Agreements: In stark contrast, interest and damages that exceed the limits of the Interest Restriction Act arise from an underlying agreement that is itself void (as per the aforementioned Grand Bench judgments). The mere arrival of the contractually stipulated due date does not give rise to a legally valid claim for such excess interest or damages. The lender, in such cases, can only have a factual expectation or hope that the borrower might choose to make voluntary payments, despite the established legal principles that protect the borrower from such obligations.

- Lack of Realization Probability: Consequently, the Court found that for unreceived excess interest, it cannot be said that there is a probability of income realization.

- Conclusion on Unreceived Excess Interest: Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that interest and damages exceeding the statutory limits, even if their contractual due date has passed, do not fall under the definition of "amounts that should be received" as per Article 10, Paragraph 1 of the Old Income Tax Act, as long as they remain unreceived. (The Court did, however, reiterate that if such excess amounts are actually received, they then constitute taxable income, as discussed earlier; the difference lies in the timing of income recognition).

- Rejection of Tax Authorities' Arguments: The tax authorities had argued that borrowers typically make these excess interest payments if possible, even knowing they are not legally obligated to do so, and that lenders have a very high likelihood of actually collecting them. They further contended that this is evidenced by the continued prevalence of lending at rates above the statutory limits, suggesting it was a common practice in informal finance, with businesses often relying on such excess interest income. The Supreme Court dismissed these arguments, stating that the mere fact that excess interest is agreed upon does not mean it will necessarily be paid, as evident from the facts of the present case. In such situations, the lender possesses no legal means whatsoever to compel payment of the excess amounts. The Court found the tax authorities' assertion that payment of excess interest is the norm to be lacking objective proof.

Summary of the Court's Position on Taxability

The Supreme Court summarized its overall findings as follows:

- If a borrower pays interest and damages, including amounts exceeding the statutory limits, according to the original agreement, and the lender receives these payments, then all such received amounts are taxable income, irrespective of the Interest Restriction Act limits.

- However, if such payments are not made within the fiscal year in which their contractual due date falls, then only the portion of the agreed interest and damages that is within the statutory limits constitutes taxable income for that year. The unreceived portion exceeding the statutory limits does not. (The Court added a crucial caveat: if excess interest has already been paid, it is legally applied to the principal first, as per the Grand Bench rulings. Therefore, whether subsequent interest accruals are within or exceed the legal limits must be calculated based on the legally valid remaining principal amount).

The Court also addressed the tax authorities' argument that distinguishing taxability based on actual receipt for excess interest would cause various practical difficulties in tax collection. While acknowledging that taxing all due amounts (received or unreceived) might be simpler, the Court stated that taxing unreceived excess interest—for which the lender has no legal means of enforcement—merely because a contractual due date has passed would violate the fundamental principle of taxation that income should ultimately be based on realized gains, unless there is proof that payment of such excess amounts is the norm. The Court further noted that when excess interest is actually received, it can be taxed, and tax authorities can ascertain the fact of payment from the borrowers. The argument that lenders could easily evade tax without meticulous bookkeeping was deemed insufficient to invalidate the Court's interpretation.

Commentary Insights

The 1971 Supreme Court decision is a cornerstone in Japanese tax jurisprudence regarding illegal income and income recognition principles.

Concept of Income in Japanese Income Tax Law

Japanese Income Tax Law does not explicitly provide a definition of "income". However, it is widely understood to adopt a "comprehensive income concept," meaning that all economic gains are considered income. This approach is also known as the "net asset increase theory," which views income as the sum of the change in net assets over a period plus consumption during that period.

Under this comprehensive view, economic gains arising from illegal or void acts are also included as taxable income. The Income Tax Basic Directive 36-1 stipulates that the "amount to be included in gross revenue" under Article 36, Paragraph 1 (of the current Income Tax Act) applies regardless of whether the act generating the revenue was lawful. Furthermore, current law provides for a subsequent claim for correction of tax if an economic gain from a void act is later lost precisely because the act was void (Income Tax Act Article 152; Income Tax Act Enforcement Order Article 274, Item 1). This implies that such gains are considered taxable unless and until they are lost.

The taxation of illegal gains signifies that income is identified based on its substantive economic reality rather than its strict legal status. From a purely legal perspective, illegal gains might not result in an increase in net assets, for example, if there is an immediate obligation to make restitution or pay damages. However, for tax purposes, they are viewed substantively as an increase in net assets and thus as income.

Excess Interest: Private Law Treatment vs. Tax Law Treatment

As the Supreme Court itself pointed out, under Japanese civil law, payments of interest exceeding the limits set by the Interest Restriction Act are not effective as interest payments but are instead applied to reduce the outstanding principal of the loan. Legally, this appears to be a recovery of capital, not the receipt of income.

However, for tax purposes, the existence of income is judged substantively. Therefore, irrespective of the strict legal evaluation, the tax implications for excess interest are determined by how the parties involved intended the payments to be made and received, and how they were actually treated and processed.

The Crucial Distinction: Unreceived vs. Received

The truly contentious issue in this case was the tax treatment of unreceived excess interest for which the payment due date had passed. It's generally accepted that interest income within legal limits is recognized for tax purposes when its due date arrives, even if it has not yet been actually collected by the lender.

Article 36, Paragraph 1 of the current Income Tax Act (and its predecessor, Article 10, Paragraph 1 of the Old Income Tax Act, relevant to this case) adopts an accrual basis rather than a strict cash basis for the timing of revenue recognition. This is commonly interpreted in Japanese tax law and practice as the "principle of established rights" (権利確定主義, kenri kakutei shugi), meaning income is recognized when the right to receive it becomes fixed and definite. However, applying the "established rights" concept to illegal gains is often problematic, as a legally enforceable "right" may not exist. For such situations, the "control/management standard" (管理支配基準, kanri shihai kijun) is often considered more appropriate for determining the timing of income recognition. This standard focuses on when the economic gain comes under the taxpayer's effective control and management.

The Supreme Court's decision in this case—specifically, not taxing unreceived excess interest due to the lack of probability of realization and the absence of any legal means for enforcement—can be understood as an application of this control/management standard to illegal gains. This principle is not limited to the specific facts of this case but applies generally to unreceived portions of interest exceeding legal limits. This judgment demonstrates that while illegal gains are generally subject to taxation, their tax treatment may differ from that of legally earned income, particularly concerning the timing of recognition.

Similar rulings were issued by the Supreme Court around the same period for both individual income tax (November 16, 1971; December 22, 1972) and corporate income tax (November 16, 1971).

Post-Facto Adjustments for Lost Illegal Gains

The principle that illegal gains constitute taxable income has a corollary: if such gains are subsequently lost due to their illegality (e.g., returned to the victim or confiscated), tax adjustments are necessary. There are generally two ways to achieve this:

- Retroactively nullify the income for the year it was originally reported. The aforementioned Income Tax Act Article 152 and its Enforcement Order provide for such a correction.

- Allow a deduction for the loss in the year the gain is actually lost. Income Tax Act Article 51, Paragraph 2, and its corresponding Enforcement Order Article 141, Item 3, stipulate that losses incurred due to the forfeiture of economic gains from a void act (which were previously included in business income, etc.) because of that act's voidness can be deducted as necessary expenses in the year the loss occurs. This deduction is generally understood to apply when the economic gain is actually returned, not merely when the obligation to return it becomes fixed.

Broader Implications and Discussion

This 1971 Supreme Court ruling carries several broader implications for understanding Japanese tax law:

- Substance Over Form in Taxing Illegal Income: The decision strongly affirms a "substance over form" approach when it comes to taxing illegal income. The economic reality of the gain to the taxpayer takes precedence over strict civil law characterizations, at least for actually received amounts.

- Probability of Realization for Accrual: The judgment highlights the critical importance of the "probability of realization" when deciding whether to accrue unreceived income. For income streams where legal enforceability is absent (as with void contracts for excess interest), the threshold for deeming income as "to be received" is significantly higher.

- Civil Law vs. Tax Law Characterization: The case clearly illustrates that the characterization of a financial flow under civil law (e.g., repayment of principal) does not automatically dictate its characterization for tax purposes (e.g., taxable income). Tax law often applies its own criteria based on economic substance and specific statutory provisions.

- Challenges for Tax Authorities: The ruling acknowledges, albeit indirectly, the practical difficulties faced by tax authorities in identifying and taxing income from informal or illegal economic activities, especially when dealing with uncollected amounts and taxpayers who may not maintain accurate records.

The "Considerations for Discussion" in the provided commentary raise interesting hypothetical questions, such as whether the Court's conclusion would have changed if the tax authorities had proven that the voluntary payment rate for excess interest was equal to that for legal interest, or how gains from a void property sale contract would be classified for income tax purposes. These reflect the ongoing complexities in applying general tax principles to specific, often unconventional, factual scenarios.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's November 9, 1971, decision provides a nuanced and principled framework for the taxation of interest that exceeds the limits set by the Interest Restriction Act. By distinguishing sharply between actually received excess interest (which is taxable upon receipt due to its substantive nature as an economic gain under the lender's control) and unreceived excess interest (which is not taxable until actually received due to the lack of legal enforceability and low probability of realization), the Court carefully balanced the comprehensive scope of taxable income with the practical and legal realities of income realization. This judgment remains a vital reference for understanding the taxation of illegal or unenforceable gains and the application of income recognition principles in Japan.