Taxing Stock Option Gains in Japan: Employment Income or Temporary Windfall? A Supreme Court Ruling

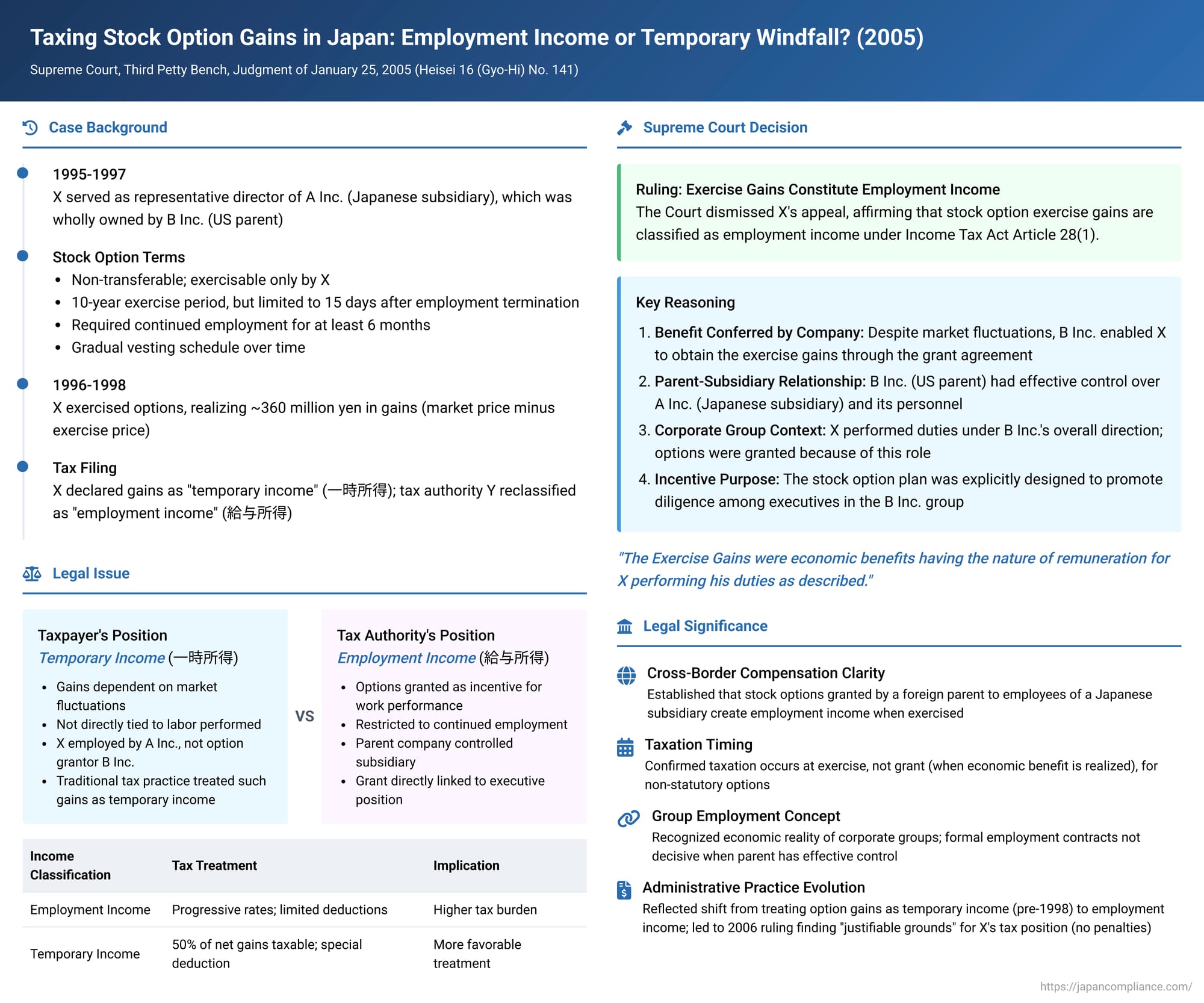

Case: Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of January 25, 2005 (Heisei 16 (Gyo-Hi) No. 141: Action for Rescission of Income Tax Reassessment Disposition, etc.)

Introduction

On January 25, 2005, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment clarifying the income tax treatment of gains realized from the exercise of stock options, particularly those granted by a foreign parent company to an executive of its Japanese subsidiary. This landmark decision addressed the contentious issue of whether such economic benefits should be classified as "employment income" (給与所得, kyūyo shotoku), subject to progressive tax rates, or "temporary income" (一時所得, ichiji shotoku), which often receives more favorable tax treatment. The ruling provided crucial clarity amidst conflicting lower court decisions and evolving tax administration practices concerning stock-based compensation.

The case involved X, a former representative director of a Japanese company, who received stock options from the company's US parent. Upon exercising these options, X realized substantial gains, which he declared as temporary income. The tax authority, Y, reclassified these gains as employment income, leading to a legal battle that culminated in this Supreme Court decision.

Facts of the Case

- Parties and Employment Context: X, the appellant, served as the representative director of A Inc., a Japanese corporation, from January 1995 to January 1997. A Inc. was a wholly-owned subsidiary of B Inc., a corporation based in the United States. B Inc. had established a stock option plan ("the Stock Option Plan") aimed at motivating diligence among certain executives and key employees within the B Inc. group of companies. During his tenure at A Inc., X was granted stock options in B Inc. ("the Stock Options") under this plan.

- Terms of the Stock Options: The Stock Options granted under B Inc.'s plan had specific conditions attached:

- They were exercisable only by the grantee (X) during his lifetime and could not be assigned, transferred, or otherwise encumbered.

- The exercise period was generally ten years from the grant date. However, if the grantee's employment relationship with any company in the B Inc. group terminated, the options were, as a rule, exercisable only for a limited period of 15 days from the date of such termination.

- Grantees were required to agree to continue their employment for at least six months from the date the options were granted.

- Furthermore, X specifically agreed that the Stock Options granted to him would vest incrementally; he could exercise a portion only after one year from the grant date, with additional portions becoming exercisable after subsequent specified periods.

- Exercise of Options and Tax Filing: X exercised the Stock Options between 1996 and 1998. By doing so, he obtained an economic benefit calculated as the difference between the market price of B Inc.'s shares at the time of each exercise and the predetermined exercise price. The total of this benefit (hereinafter "the Exercise Gains") amounted to approximately 360 million yen over the three years. X filed his income tax returns for the years 1996 through 1998, declaring the Exercise Gains as temporary income under Article 34, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act.

- Tax Authority's Reassessment and Legal Challenge: The director of the competent tax office, Y (the appellee), took a different view. Y determined that the Exercise Gains constituted employment income as defined in Article 28, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act. Consequently, on February 29, 2000, Y issued reassessment dispositions for X's income tax for the said years, resulting in increased tax liabilities. (A portion of the reassessment for the 1996 tax year was later cancelled by an administrative appeal decision on July 28, 2000 ). X disputed these reassessments and sought their cancellation.

- Lower Court Rulings: The Tokyo District Court, in the first instance, ruled in favor of X, agreeing that the Exercise Gains should be classified as temporary income. However, the Tokyo High Court, acting as the second instance court, overturned this decision and sided with the tax authority, Y, classifying the Exercise Gains as employment income. X subsequently appealed this High Court ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision that the Exercise Gains constituted employment income. The Court's reasoning focused on the nature of the benefit received and its connection to X's services.

Nature of the Benefit Conferred by B Inc.

The Court first analyzed how the economic benefit arose:

- The Stock Options were explicitly non-transferable and could only be exercised by X during his lifetime. This meant that X could only realize any economic benefit from these options by personally exercising them.

- Therefore, B Inc., by granting X the Stock Options under the terms of the Stock Option Plan and the specific grant agreement, and by subsequently allowing X to acquire B Inc. shares at the predetermined exercise price, effectively enabled X to obtain the Exercise Gains.

- Based on this, the Supreme Court concluded that the Exercise Gains were a "benefit provided by B Inc. to X".

- The Court also addressed the argument that the actual realization and amount of the Exercise Gains were dependent on the fluctuating market price of B Inc.'s stock and X's own judgment regarding the timing of exercise. It held that these factors did not negate the fundamental nature of the Exercise Gains as a benefit conferred upon X by B Inc..

Characterization as Remuneration for Services

The Court then examined the link between these benefits and X's employment:

- It was established that B Inc. held 100% of the issued shares of A Inc., X's direct employer. This ownership structure indicated that B Inc. possessed effective control over A Inc., including practical authority over A Inc.'s executive personnel matters. Consequently, the Court viewed X as performing his duties as the representative director of A Inc. under the overall direction and supervision of B Inc..

- The Stock Option Plan itself was explicitly designed as an incentive to promote diligence among executives and key employees within the entire B Inc. group.

- The Supreme Court reasoned that B Inc. entered into the stock option grant agreement with X, thereby granting him the Stock Options, precisely because X was performing his duties as described within this group structure.

- From these facts, the Court found it "clear that the Exercise Gains were economic benefits having the nature of remuneration for X performing his duties as described".

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the Exercise Gains fell under the definition of employment income as stipulated in Article 28, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act, because they were benefits provided as "consideration for non-independent labor furnished under an employment contract or a similar cause". The Court also noted that legal precedents cited by X in his arguments were not pertinent to the specifics of this case.

Thus, the reassessments made by the tax authority, which treated the Exercise Gains as employment income, were deemed lawful.

Commentary Insights

This Supreme Court decision is a pivotal one in Japanese tax law concerning stock-based compensation and has been the subject of extensive commentary.

Significance of the Ruling Amidst Conflicting Interpretations

The primary legal battle in this case was the classification of stock option exercise gains – specifically those granted by a foreign parent company to an executive of its Japanese subsidiary – as either employment income or temporary income. The Supreme Court's judgment was crucial as it provided a definitive judicial pronouncement on this issue, particularly important because lower courts had previously delivered conflicting rulings on similar matters.

It's important to note the existing statutory framework for certain types of stock options in Japan. Article 84, Paragraph 2 of the Income Tax Act Enforcement Order specifies that gains from exercising stock options that fall under Japan's Companies Act are considered taxable income under Article 36 of the Income Tax Act (which deals with the calculation of revenue amounts). Additionally, Article 29-2 of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation provides for tax deferral until the time of share sale for certain qualifying stock options issued under the Companies Act. However, the stock options in X's case were granted by a foreign parent company and did not fall under these specific Japanese statutory provisions. This absence of direct statutory coverage led to interpretative questions regarding the timing of taxation and, critically, the income classification of the exercise gains.

Timing of Stock Option Taxation: Grant vs. Exercise

Academic discussions on stock option taxation typically identify three potential points in time for taxation: the date of grant, the date of exercise, or the date of subsequent sale of the acquired shares.

- In X's case, the first instance court (Tokyo District Court), while acknowledging that stock options might possess economic value at the time of grant as a form of "right of expectation" (期待権, kitaiken), found the practical valuation of this right at grant to be problematic.

- The second instance court (Tokyo High Court) viewed the stock options at grant as merely a "right to conclude a sale preemption contract" (予約完結権, yoyaku kanketsuken), considering that the grantee had not yet acquired a right that would generate actual income from the perspective of the "principle of established rights" (権利確定主義, kenri kakutei shugi) for income recognition.

- The Supreme Court, emphasizing the non-transferability of the Stock Options in this case, reasoned that X could only obtain an actual economic benefit upon exercising them.

Thus, all three court levels—District, High, and Supreme—consistently ruled out taxation at the time of grant and affirmed that the taxable event occurred at the time of exercise.

Rationale for Classification as Employment Income

The classification of the Exercise Gains as employment income involved a detailed analysis, particularly in relation to a prior Supreme Court precedent from 1981 (Showa 56.4.24, Minshu Vol. 35, No. 3, p. 672; often referred to as the "Lawyer Retainer Fee Case" and discussed as Case 38 in the source material series). That 1981 case defined employment income as "remuneration received from an employer as consideration for labor provided under an employer's direction and control, based on an employment contract or a similar cause".

- Benefit from Granting Company and Consideration for Labor:

- The first instance court had argued that the Exercise Gains could not be considered a direct benefit from B Inc. because their realization depended on contingent stock price movements and X's personal decision on when to exercise the options. It also denied that the gains were remuneration for labor performed for B Inc., as X was formally employed by A Inc., not B Inc..

- The second instance court, however, characterized the Exercise Gains as a "transfer of economic benefit from the granting company to the grantee," which was agreed upon in the stock option grant contract.

- The Supreme Court aligned with the second instance court on this point, stating that B Inc. enabled X to obtain the Exercise Gains through the grant agreement. It further held that these gains were indeed consideration for X performing his duties for A Inc., services which B Inc. desired due to its overarching group interest and control structure.

- Discrepancy Between Directing Authority and Paying Entity:

- A key issue was that X's formal employment contract was with A Inc. (the Japanese subsidiary), while the stock options (and thus the Exercise Gains) were provided by B Inc. (the US parent). The first instance court had emphasized the lack of a direct employment contract between X and B Inc., suggesting that X's work for A Inc. had only an "indirect and tenuous link" to B Inc.'s performance.

- In contrast, the second instance court took the view that the diligent performance of employees in a subsidiary directly benefits the parent company.

- The Supreme Court adopted a stance similar to the second instance court. It reasoned that B Inc., by "holding practical authority over personnel matters, etc., and controlling" A Inc., effectively created a situation where X's diligent service within the B Inc. group was the intended object of the Stock Option Plan's incentives. Therefore, the fact that the entity providing the direction (B Inc., implicitly) and the entity paying salary (A Inc.) were distinct from the entity granting the options (B Inc.) did not prevent the Exercise Gains from being classified as employment income.

- The commentary notes that the second instance court had also opined that the definition of employment income in Article 28 of the Income Tax Act and the precedent of the 1981 Supreme Court case did not strictly require the directing authority and the paying entity to be identical. The Supreme Court, in its judgment (Reasoning, Point II), stated that the 1981 precedent X cited was "not appropriate for this case" when discussing this particular aspect. The commentary clarifies that this 2005 Supreme Court decision should be viewed as a judgment specific to its facts and does not offer a new, overarching definition of employment income intended to replace the general principles established in the 1981 "Lawyer Retainer Fee Case".

Historical Context of Tax Practice and "Justifiable Grounds"

Academically, various classifications for stock option exercise gains have been proposed, including employment income, temporary income, capital gains income (譲渡所得, jōto shotoku), or miscellaneous income (雑所得, zatsu shotoku). The application of a "dual gain theory" (二重利得法, nijūritokuhō), which might involve segregating different economic components of the gain, was denied in a 2004 Tokyo District Court case.

The pronounced conflict in X's case between classifying the gains as employment income versus temporary income stemmed largely from a historical shift in tax administration practice. Until around 1998, the prevailing practice was often to treat stock option exercise gains as temporary income. However, practice subsequently shifted towards classifying them as employment income. This change in administrative interpretation was later explicitly stated in a 2002 amendment to the Basic Directives of the Income Tax Act (specifically, Basic Directive 23-35 Common-6(2)(a), prior to its 2019 revision). This period of evolving practice caused considerable confusion among taxpayers.

In X's case, his argument that he acted in good faith by relying on the older practice (classifying as temporary income) was rejected by the lower courts on the main issue of income classification, and this aspect was excluded from the Supreme Court's review on procedural grounds (Article 318, Paragraph 3 of the Code of Civil Procedure). However, in a separate but related Supreme Court judgment dated October 24, 2006 (Minshu Vol. 60, No. 8, p. 3128), the Court found that X had "justifiable grounds" (正当な理由, seitō na riyū) under Article 65, Paragraph 4 of the Act on General Rules for National Taxes for declaring the Exercise Gains as temporary income, given the past changes in tax treatment. Consequently, the imposition of an underpayment penalty on X was deemed unjustified in that separate ruling.

Recent Trends in Equity Compensation in Japan

The commentary also notes that in recent years, there has been an increasing trend in Japan towards using "full-value" type equity compensation, such as restricted stock and performance stock awards, rather than solely relying on appreciation-based instruments like traditional stock options. In these full-value schemes, employees typically receive actual shares, so the concept of "exercise-time taxation" as seen with options is not directly applicable. For these types of equity compensation, where the economic benefit is tied to the market value of shares (which fluctuates), disputes have primarily centered on the timing of taxation. For instance, with restricted stock, potential taxable moments could be the time of grant, the time when transfer restrictions are lifted (vesting), or the time of subsequent sale. Japanese courts, applying the "principle of established rights," have generally held that for restricted stock, the taxable event occurs when the transfer restrictions are removed, and the taxable economic benefit is the market value of the shares at that point in time (e.g., Tokyo District Court judgment, December 16, 2005; this aligns with provisions like Article 84, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act Enforcement Order). The principles regarding income classification established in this 2005 Supreme Court stock option case continue to be influential in these newer contexts of equity compensation.

Broader Implications and Discussion

The Supreme Court's 2005 decision has several important implications:

- Broad Interpretation of Employment Relationship: The ruling suggests a broad interpretation of what constitutes an "employment contract or a similar cause" for the purpose of defining employment income. It encompasses situations where an executive of a subsidiary receives benefits from a parent company, provided there's a clear link to services rendered within the group structure under the parent's overall control and incentive framework.

- Focus on Incentive Nature: The Court heavily emphasized the incentive nature of the stock option plan. If a benefit is provided to motivate diligence and continued service, it is strongly indicative of remuneration for labor, and thus, employment income.

- Confirmation of Exercise-Time Taxation: For stock options not covered by specific statutory deferral regimes (like those for certain domestic options), this case reinforces the principle of taxation at the time of exercise, when the economic benefit becomes tangible and measurable, especially if grant-time valuation is uncertain or the options are non-transferable.

- Impact on Multinational Companies: The decision has significant practical implications for multinational corporations that use global stock option plans to compensate employees and executives of their Japanese subsidiaries. It clarifies that gains from such options will generally be treated as employment income in Japan, subject to Japanese income tax rules and potentially withholding obligations.

The "Considerations for Discussion" in the provided commentary prompt further thought on related issues, such as the corporate income tax treatment for the granting company and its consistency with the income tax treatment for the recipient, and the taxation of newer forms of equity compensation like stock units, particularly regarding the timing of income recognition when internal company rules and vesting schedules interact.

Conclusion

The Japanese Supreme Court's January 25, 2005, judgment definitively classified the economic gains from exercising stock options granted by a foreign parent company to an executive of its Japanese subsidiary as employment income. The Court's reasoning centered on the benefit being conferred by the parent company in direct connection with the executive's services performed within the corporate group, driven by an incentive scheme designed to promote diligence. This decision underscored the importance of the substance of the arrangement over formal employment contracts in determining the nature of income for tax purposes and provided critical guidance for the taxation of cross-border equity compensation in Japan. It affirmed that such gains are generally viewed as remuneration for labor, subject to taxation as employment income at the time of exercise.