Taxed on Someone Else's Income? Japanese Supreme Court on When Erroneous Assessments Are Void

Date of Judgment: April 26, 1973

Case Name: Claim for Confirmation of Invalidity of Income Tax Assessment Disposition, etc. (昭和42年(行ツ)第57号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

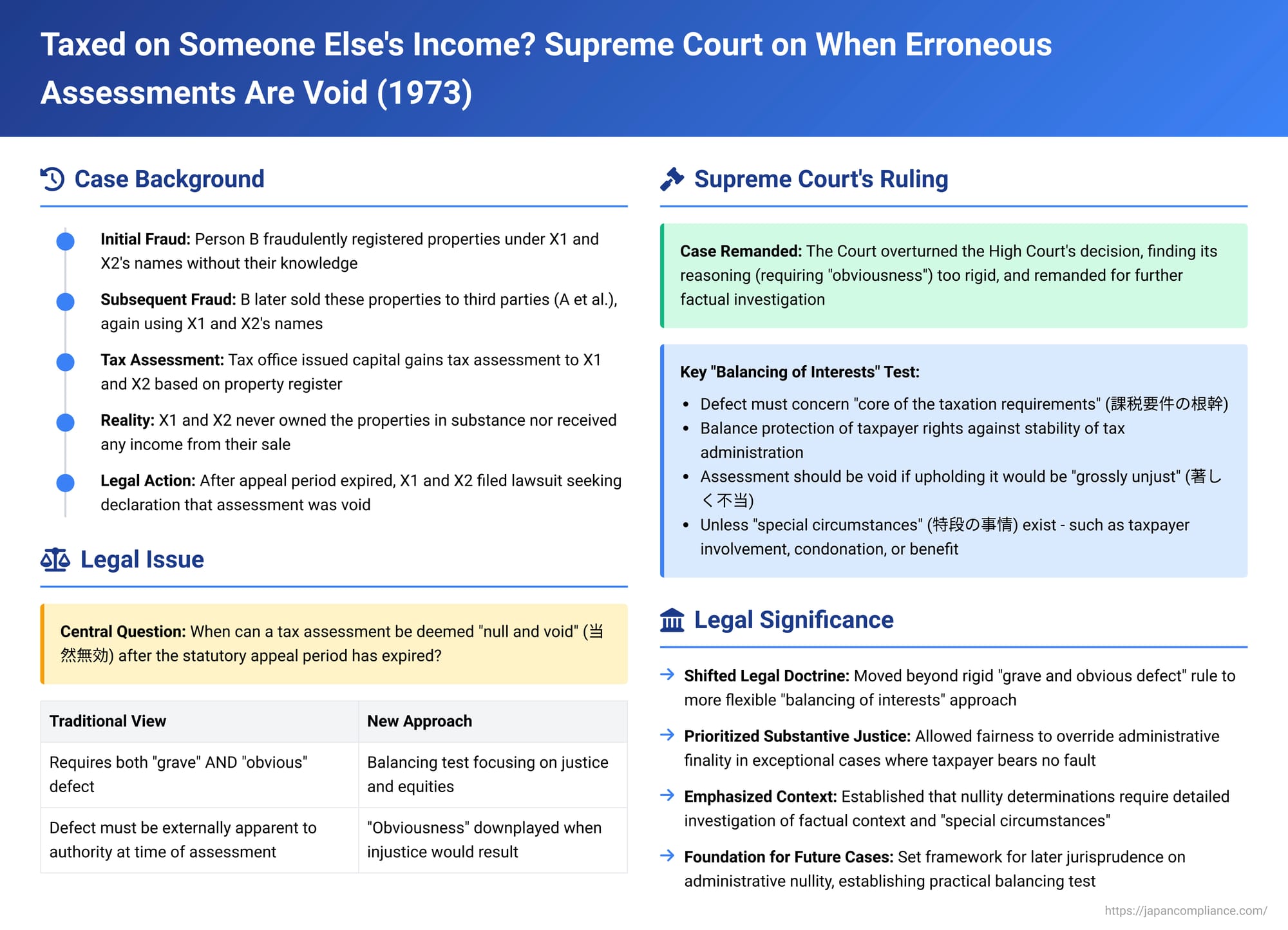

In a landmark decision on April 26, 1973, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the critical question of when an income tax assessment can be deemed "null and void" (muko - 無効), particularly when the assessment erroneously attributes income to a taxpayer who never actually received it. This case is pivotal for establishing a "balancing of interests" test for determining nullity, moving beyond a rigid application of the traditional "grave and obvious defect" doctrine, especially when the statutory period for appealing the assessment has passed.

A Case of Stolen Identity and Misattributed Income

The appellants, X1 and X2, were individuals who found themselves subject to an income tax assessment for capital gains. The tax office head, Y, had issued this assessment based on entries in the property register which indicated that X1 and X2 had transferred ownership of certain land and buildings to other parties (A et al.).

However, the reality was starkly different. A de facto relative of X1 and X2, an individual named B, had, without their knowledge or consent, fraudulently used their names to effect these property registrations. Initially, B, who was the true owner of the properties (though they were registered under third-party names), had created a provisional registration transferring title to X1, and a full ownership registration transferring title of another property to X2. Years later, B, still acting without X1 and X2's authorization, fabricated documents using their names and seals to complete the registration of X1 as owner of the first properties and then to transfer ownership of all the properties from X1 and X2 to A et al., with B receiving all the sales proceeds. Essentially, X1 and X2 were merely nominal titleholders due to B's unauthorized actions; they never owned the properties in substance nor received any income from their sale.

After the statutory period for appealing the tax assessment against them had expired, X1 and X2 filed a lawsuit. They sought a court declaration that the assessment was null and void due to a "grave and obvious defect" (重大かつ明白な瑕疵 - jūdai katsu meihaku na kashi), arguing that they had no connection to the income-generating transaction.

The lower courts (Yokohama District Court and Tokyo High Court) acknowledged that there was indeed a "grave defect" in Y's tax assessment, as it taxed individuals for income that was not theirs. However, both courts dismissed X1 and X2's claim for nullity. Their reasoning was that while the defect was grave, it was not "externally and objectively obvious" to the tax office at the time the assessment was made; the tax office had relied on the property register, which, on its face, implicated X1 and X2. X1 and X2 then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Question: When is a Flawed Tax Assessment "Null and Void"?

Under Japanese administrative law, tax assessments, like other administrative dispositions, generally acquire an "effect of becoming incontestable" (不可争的効果 - fukasōteki kōka, often shortened to 不可争力 - fukasōryoku) once the statutory period for filing an administrative appeal or a lawsuit for revocation has passed. This principle ensures legal stability and the smooth operation of administration.

However, there is an exception: if an administrative disposition suffers from a defect so severe that it is considered "null and void" (tōzen mukō - 当然無効), it is treated as having had no legal effect from its inception. Such a void disposition can be challenged at any time, even after the usual appeal periods have lapsed. The critical legal question in this case was what kind of defect renders a tax assessment null and void, especially when income is attributed to the wrong person. Specifically, is it essential for the defect to have been "obvious" to the tax authority at the time of the assessment, as the lower courts had held?

The Supreme Court's Landmark "Balancing of Interests" Test

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further factual investigation. The Court found that the High Court's reasoning (which strictly required external obviousness of the defect) was flawed and that the assessment against X1 and X2 could indeed be null and void, depending on a fuller examination of the circumstances.

The Supreme Court laid out a framework for determining the nullity of a tax assessment, emphasizing a balancing of competing interests:

- Grave Defect in a Core Taxation Requirement: The Court first affirmed that the error in the assessment must be fundamental, concerning the "core of the taxation requirements" (課税要件の根幹 - kazei yōken no konkan). In this case, taxing X1 and X2 for capital gains income that they had never actually received, and which belonged entirely to B, constituted such a "grave error."

- Balancing of Interests: Even if a grave defect exists, a determination of nullity requires a careful balancing of several values:

- (a) Protection of the Taxpayer's Rights: The interest of the individual in not being subjected to an unlawful tax burden.

- (b) Stability and Smooth Operation of Tax Administration: The public interest in ensuring that tax assessments become final and that tax collection can proceed efficiently.

- (c) Protection of Third Parties Relying on the Assessment: The interest of any third parties who might have acted in good faith relying on the apparent validity of the assessment. (The Court noted that this third-party protection aspect was not a significant factor in the present case, as the dispute was primarily between the taxpayers and the tax authority).

- "Grossly Unjust" Outcome and "Special Circumstances": The Court stated that an assessment with such a grave defect should be deemed null and void if forcing the taxpayer to bear the burden of that assessment, despite the lapse of the normal appeal period, would be "grossly unjust" (著しく不当 - ichijirushiku futō). This would be the case unless "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) exist. Such "special circumstances" might include situations where:

- The taxpayers (X1 and X2) were not entirely uninvolved in or unaware of the chain of fraudulent registrations.

- The taxpayers had subsequently, either explicitly or implicitly, condoned the erroneous registrations made in their names.

- The taxpayers had derived some form of special benefit from the apparent legal relationship created by the fraudulent registrations.

- Impact on Tax Administration: The Court also considered the potential impact on tax administration. It noted that cases of such fraudulent use of names for tax purposes were likely "relatively rare." Furthermore, if the true facts became known, there might still be a possibility of taxing the actual income earner (B). Therefore, nullifying the erroneous assessment against X1 and X2 would not necessarily cause "particular hindrance or obstruction to tax administration" (徴税行政上格別の支障・障害をもたらすともいい難い - chōzei gyōseijō kakubetsu no shishō・shōgai o motarasu tomo iigatai).

- Conclusion on X1 & X2's Initial Case (as presented by lower courts): Based solely on the facts as initially found by the lower courts (which portrayed X1 and X2 as essentially unknowing victims of B's fraud), the Supreme Court suggested that this situation appeared to be one of those "exceptional circumstances" where it would be grossly unjust to hold X1 and X2 to the flawed tax assessment, especially given their lack of culpability. In such a scenario, the grave defect would render the assessment null and void.

Why Remand? The Nuance of "Special Circumstances"

Despite this initial inclination, the Supreme Court remanded the case to the Tokyo High Court for further factual inquiry. The reason for the remand lay in other findings of the first instance court (which the High Court had cited). These findings suggested that B's initial unauthorized registration of the properties in X1 and X2's names might have been linked to a loan X1 and X2 had made to B, with the registrations serving as a form of informal security for this loan, or possibly as a way for B to shield the properties from his own creditors.

The Supreme Court reasoned that if X1 and X2 had, in fact, a pre-existing financial relationship with B, and if the registrations (though unauthorized) were not entirely disadvantageous to them at the outset (e.g., if they served to secure their loan to B), or if X1 and X2 later became aware of B's misuse of their names and implicitly or explicitly condoned it, or if they derived some benefit from this situation (e.g., if their loan was repaid using the proceeds from the sale of the properties), then the "special circumstances" might change the equitable balance. In such a scenario, forcing them to bear the consequences of the flawed tax assessment might not be deemed "grossly unjust."

The High Court had prematurely concluded that the assessment was not void by focusing too narrowly on the lack of "obviousness" of the defect to the tax authorities at the time of assessment, without fully investigating these potential "special circumstances" relating to X1 and X2's involvement, knowledge, condonation, or derived benefits.

Analysis and Significance

This 1973 Supreme Court judgment is a landmark decision in Japanese administrative and tax law for several key reasons:

- Shift from a Rigid "Grave and Obvious Defect" Rule: The decision is widely seen as moving away from a strict, two-pronged "grave AND obvious defect" test (重大明白説 - jūdai meihaku setsu) for determining the nullity of an administrative act. While acknowledging the need for a "grave" defect concerning a core requirement, the Supreme Court significantly downplayed the necessity for the defect to be "obvious" (externally apparent to the administrative agency at the time of the act) if other factors, particularly the potential for gross injustice to the individual, weighed heavily in favor of nullity. Instead, it introduced a more flexible "balancing of interests" approach.

- Focus on Substantive Justice over Administrative Finality in Exceptional Cases: The ruling prioritizes preventing "grossly unjust" outcomes for taxpayers who are erroneously assessed, especially for income they demonstrably did not receive and where they bear no fault for the error's initial occurrence in the tax records. It allows the principle of substantive justice to override the general interest in the finality of administrative acts (fukasōryoku) in these exceptional circumstances.

- Importance of Factual Context and "Special Circumstances": The Supreme Court highlighted that determining whether an assessment is null and void is highly dependent on the specific facts of each case. The inquiry into "special circumstances"—particularly any actions, knowledge, condonation, or benefits on the part of the taxpayer related to the erroneous basis of the assessment—is crucial. The outcome of the remanded High Court hearing in this very case (which ultimately found that such "special circumstances" did exist to X1 and X2's detriment, leading to the denial of their claim) underscores the critical nature of this detailed factual investigation.

- Guidance for Later Jurisprudence: While legal scholarship continues to debate the precise contours of the nullity doctrine (with theories like the "obviousness as a supplementary requirement theory" - 明白性補充要件説 meihakusei hojū yōken setsu, and the "concrete value balancing theory" - 具体的価値衡量説 gutaiteki kachi kōryō setsu being discussed), this Supreme Court decision provided a foundational framework emphasizing a balancing of values. Subsequent Supreme Court cases, while sometimes still referencing the "grave and obvious" terminology, have often engaged in a practical balancing of interests similar to that outlined in this 1973 ruling.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1973 decision significantly refined the criteria for when a tax assessment in Japan can be considered null and void, particularly after the ordinary appeal periods have expired. It established that even if an error is not immediately obvious to the tax authorities at the time of assessment, an assessment may still be voided if it suffers from a grave defect concerning a core taxation requirement (such as taxing the wrong person for income) AND if upholding the assessment would lead to a grossly unjust result for a taxpayer who is not otherwise at fault or did not benefit from the circumstances leading to the error. This landmark judgment underscores a judicial commitment to balancing the need for administrative finality and efficiency with the fundamental principles of substantive justice and fairness to the taxpayer.