Taxation by Law or by Circular? The Japanese Supreme Court's "Pachinko Machine Case"

Judgment Date: March 28, 1958

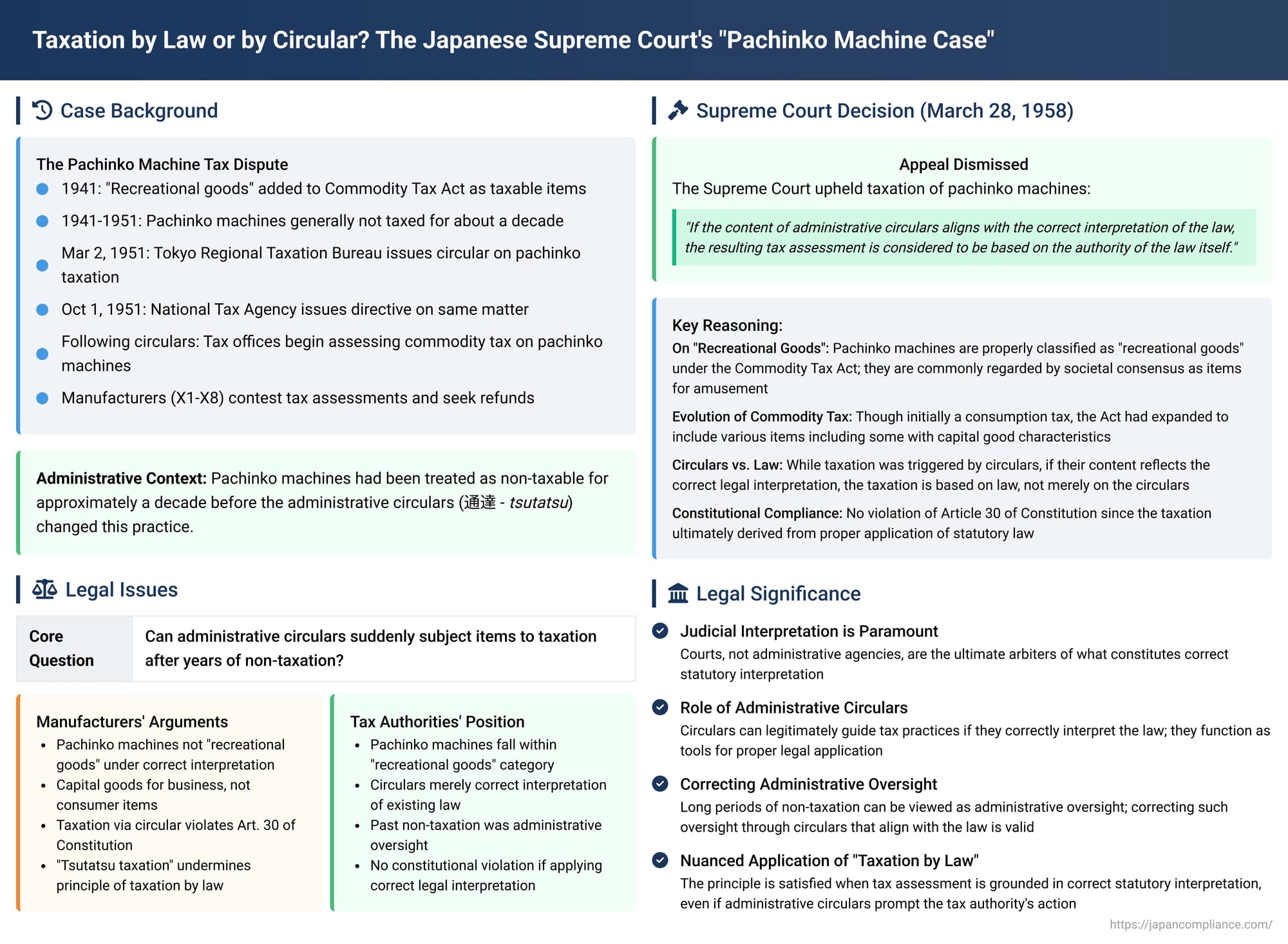

In a landmark decision with enduring significance for Japanese tax law, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the contentious issue of "tsutatsu taxation"—taxation seemingly based on administrative circulars—and its relationship with the constitutional principle of "taxation by law." The case, commonly known as the "Pachinko Machine Case," centered on whether pachinko machines were taxable as "recreational goods" under the former Commodity Tax Act and whether a change in long-standing administrative practice, prompted by internal tax agency circulars, was a legitimate application of the law or an unconstitutional overreach.

Background: Pachinko Machines and the Commodity Tax

The appellants, a group of eight individuals and manufacturing companies (collectively referred to as X1-X8), were producers of pachinko machines. The legal dispute arose from the application of the former Commodity Tax Act. In 1941, the term "recreational goods" (遊戯具 - yugigu) was added to Article 1 of this Act, which listed taxable items.

For a significant period, approximately a decade following this amendment, pachinko machines were, with very few exceptions, not subjected to commodity tax by the tax authorities. This period of non-taxation formed a crucial part of the appellants' arguments.

The administrative landscape shifted in 1951. On March 2nd of that year, the Director of the Tokyo Regional Taxation Bureau issued an administrative circular (tsutatsu). This was followed on October 1st by a directive (tsucho, a similar form of internal communication) from the Director-General of the National Tax Agency. Both these internal administrative communications indicated that pachinko machines were indeed to be considered "recreational goods" under the Commodity Tax Act and were therefore taxable.

Prompted by these circulars, the heads of the relevant local tax offices (Y1-Y5, the appellees, along with the State) began to assess commodity tax on the pachinko machines manufactured by X1-X8. The manufacturers contested these assessments, arguing they were invalid. Those among them who had already paid the tax also sought its refund.

The Appellants' Core Arguments

X1-X8's challenge rested on two main pillars:

- Statutory Interpretation of "Recreational Goods": They argued that pachinko machines did not fall within the scope of "recreational goods" as intended by the Commodity Tax Act. Their reasoning was that commodity tax was fundamentally aimed at goods intended for final, private consumption (consumer goods). Pachinko machines, they contended, were primarily capital goods used by pachinko parlor operators to generate income, not items for personal, consumptive use.

- Unconstitutionality of "Tsutatsu Taxation": This was their constitutional challenge. X1-X8 asserted that the imposition of tax based on a new interpretation introduced by administrative circulars, especially after a prolonged period of established non-taxation, violated Article 30 of the Constitution of Japan. Article 30 states: "The people shall be liable to taxation as provided by law." The appellants interpreted this to mean that taxation must be based directly on laws enacted by the Diet, not on administrative orders or interpretations that abruptly alter long-standing practices. They argued that if administrative agencies could change established non-taxation into taxation through mere circulars, the constitutional principle of taxation by law would be undermined. The shift from non-taxation to taxation of pachinko machines, triggered by the 1951 circulars, was, in their view, an unconstitutional act of "tsutatsu taxation."

The lower courts, the Tokyo District Court and the Tokyo High Court, had ruled against X1-X8, generally finding the tax assessments not to be inherently invalid. The High Court upheld the District Court's dismissal of the appellants' claims.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, upon reviewing the appeal, dismissed it, upholding the decisions of the lower courts. The Court's reasoning addressed both the statutory interpretation and the constitutional challenge.

1. Interpreting "Recreational Goods" in the Commodity Tax Act

The Court first tackled the question of whether pachinko machines were, by law, "recreational goods."

- Evolution of Commodity Tax: The Court acknowledged that the Commodity Tax Act, when first implemented in 1929, began as a form of consumption tax. However, over time, its scope had progressively broadened to include items that were not strictly for final private consumption. Daily necessities and what the Court termed "capital-like consumer goods" were gradually added to the list of taxable items.

- Examples of Taxable Capital-like Goods: By the time the version of the Commodity Tax Act relevant to the case (the 1940 Act) was enacted, the list of taxable items already included some daily necessities (e.g., matches) and items that could be considered capital goods or possess capital good characteristics. The Court cited "billiard tables" and "passenger automobiles" as examples of such items listed in the Act. Subsequent amendments had further expanded this category.

- Relativity of "Consumer" vs. "Capital" Goods: The Court observed that the distinction between "consumer goods for final consumption" (goods used up by individuals) and "productive consumer goods" (goods used to produce other goods or services, i.e., capital goods) is inherently relative.

- Dual Nature of Pachinko Machines: While pachinko machines were used commercially in parlors, the Court stated that they could not be said to be entirely devoid of characteristics as goods for personal consumption.

- Societal Understanding: Considering these points, alongside other reasons cited in the lower court judgments, the Supreme Court found it difficult to conclude that pachinko machines—which were commonly regarded by societal consensus as items for amusement or recreation—would not be included within the Commodity Tax Act's category of "recreational goods."

The Supreme Court affirmed the lower court's interpretation that pachinko machines were included in "recreational goods" under the existing law. It explicitly stated that this was not merely a policy argument about the desirability of taxing pachinko machines but a correct interpretation of the then-current statute.

2. Addressing the "Tsutatsu Taxation" Claim

Having established that pachinko machines were legally taxable as "recreational goods," the Court then turned to the constitutional argument regarding "tsutatsu taxation."

- The Role of Circulars: The Court acknowledged the appellants' argument that the taxation was unconstitutional because it was based on administrative circulars.

- Alignment with Correct Legal Interpretation is Key: The pivotal point in the Court's reasoning was: even if the taxation in this specific instance was triggered or occasioned by the issuance of the administrative circulars, as long as the content of those circulars aligns with the correct interpretation of the law, the resulting tax assessment is considered to be a処分 (disposition/assessment) based on the authority of the law itself.

- Appellants' Premise Flawed: The Court stated that the appellants' claim of unconstitutionality was predicated on the assumption that the interpretation contained in the circulars (i.e., that pachinko machines are taxable "recreational goods") was not consistent with the law.

- Conclusion on Constitutionality: Since the Supreme Court had already determined that the interpretation within the circulars was a correct reflection of the Commodity Tax Act, the argument that the taxation based on this interpretation was unconstitutional could not be accepted. In effect, the tax was levied based on the law, not merely on the circular.

Therefore, the Supreme Court found no grounds to declare the tax assessments inherently invalid and dismissed the appeal.

Significance and Implications of the "Pachinko Machine Case"

The "Pachinko Machine Case" is a cornerstone judgment in Japanese tax law for several reasons:

- Judicial Interpretation of Tax Law: It firmly establishes the role of the judiciary as the ultimate arbiter of tax statute interpretation. While administrative agencies like the National Tax Agency issue circulars to guide their officials and ensure uniform application of tax laws, these interpretations are subject to judicial review.

- Validity of Administrative Circulars (Tsutatsu): The decision clarifies that tsutatsu, while not laws themselves and generally considered internal administrative guidelines without direct binding force on taxpayers, can play a legitimate role in tax administration. If a circular accurately reflects the correct meaning of a tax statute, actions taken by tax officials in accordance with that circular are deemed to be actions based on the law itself. The circular, in such cases, acts as a tool for proper legal application.

- Addressing Changes in Administrative Practice: The case implicitly addressed situations where long-standing administrative practice is altered. By finding that the taxation of pachinko machines was legally correct under the statute all along, the Court suggested that the prior period of non-taxation was effectively an administrative oversight or a "tax loophole." Correcting such an oversight through circulars that align with the law does not constitute the creation of new tax obligations by administrative fiat; rather, it represents a move towards enforcing the existing law correctly.

- The "Taxation by Law" Principle: The ruling provides a nuanced understanding of Article 30 of the Constitution. It indicates that the principle of "taxation by law" is satisfied if the tax assessment is grounded in a correct interpretation of a duly enacted statute, even if an administrative circular serves as the proximate cause for the tax authority's action or a change in its enforcement stance.

The "Pachinko Machine Case" sparked considerable academic debate, particularly concerning the nature of long-standing administrative practices. Some scholars argued that a consistent, long-term non-taxation practice might create a legitimate expectation for taxpayers, akin to an "administrative precedent law," which should not be overturned by mere internal circulars but only by formal legislative amendment. This perspective emphasizes the importance of taxpayer reliance and legal stability.

The Supreme Court, however, in this instance, prioritized the "correct" interpretation of the statute as determined by the judiciary. The implication was that if the statute, correctly interpreted, always covered pachinko machines, then the prior non-taxation was an error, and its correction via circular (leading to taxation) was lawful.

This judgment did not extensively delve into the principles of "protection of legitimate expectations" or "non-retroactivity" in the context of changing interpretations for past periods, as the primary challenge was to the validity of the current assessments based on the new administrative stance. However, it laid a foundational understanding that the ultimate source of tax liability must be the law itself, and administrative circulars derive their legitimacy from their conformity with that law.