Tax Without Real Income? Japan's Supreme Court on Unjust Enrichment and 'Objectively Clear' Bad Debts

Judgment Date: March 8, 1974

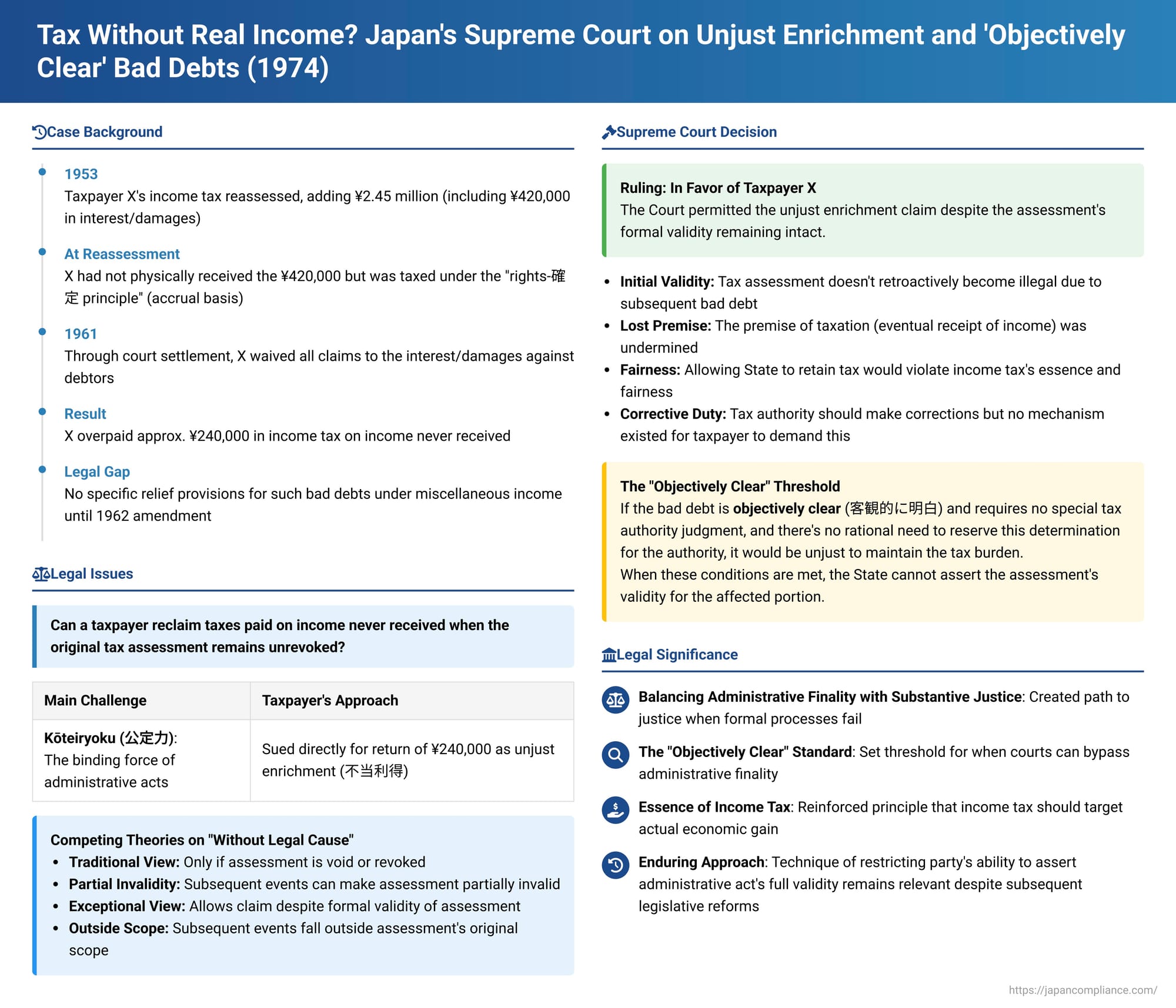

The principle of unjust enrichment, where a party unfairly benefits at another's expense without legal justification, is a cornerstone of private law. Its application in the realm of public law, especially concerning tax matters, often encounters the formidable presence of formally established administrative acts. A pivotal Japanese Supreme Court decision from March 8, 1974 (Showa 43 (O) No. 314), grappled with such a scenario, exploring whether a taxpayer could reclaim taxes paid on income that, due to subsequent events, was never actually received, even when the original tax assessment remained formally unrevoked. This case navigates the delicate balance between administrative finality and substantive justice.

The Taxpayer's Predicament: Taxed on Income Never Received

The case involved a taxpayer, X, whose income tax for the year 1953 was subjected to an upward reassessment by the Asakusa Tax Office Director[cite: 1]. This reassessment added approximately 2.45 million yen to X's declared total income, classifying it as miscellaneous income[cite: 1]. A significant portion of this addition, about 420,000 yen, pertained to interest and damages accrued on loans X had provided to other parties, collectively referred to as A[cite: 1].

Crucially, at the time of the tax assessment, X had not yet actually received this 420,000 yen[cite: 1]. The Japanese income tax system, under a principle known as kenri kakutei shugi (権利確定主義), often translated as the "rights- 확정 principle" or accrual basis of accounting, recognizes income when the right to receive it becomes definitively established, regardless of whether the cash has physically changed hands[cite: 1]. This principle assumes that the right will eventually translate into actual receipt and is adopted for reasons of tax policy, including ensuring fairness and preventing taxpayers from arbitrarily delaying tax liability by controlling the timing of actual receipt[cite: 1].

However, X's situation took a sharp turn in 1961. Through a court settlement, X was compelled to waive all claims to the aforementioned interest and damages against parties A[cite: 1]. This event effectively transformed the recognized income into a bad debt; the 420,000 yen that had been legally recognized as X's income now, retrospectively, ceased to exist as an economic gain[cite: 1]. As a direct consequence, X had effectively overpaid income tax by an amount corresponding to this "vanished" income, calculated to be approximately 240,000 yen, which the State (Y) had collected and retained[cite: 1].

The legal framework at the time presented a significant challenge for X[cite: 1]. While the Income Tax Act did have provisions for addressing bad debts, these primarily concerned bad debts arising from business income, which could be treated as necessary expenses in the year the bad debt occurred[cite: 1]. For miscellaneous income, like X's interest income, there were no specific adjustment or relief provisions in the Income Tax Act for such subsequently occurring bad debts until an amendment in 1962[cite: 1]. However, this 1962 amendment (specifically, Supplementary Provision Article 7) stipulated that the new relief measures would only apply to bad debts arising on or after January 1, 1962[cite: 1]. Since X's bad debt effectively crystallized with the 1961 court settlement, these new provisions were inapplicable, leaving X in a legislative gap[cite: 1]. The then-existing Income Tax Act did not envisage a procedure for X to recover this 240,000 yen overpayment[cite: 1].

The Legal Challenge: Kōteiryoku vs. Fairness

X sought recourse through the courts[cite: 1]. The core issue was how to address the original tax reassessment, which, though valid when issued, had become substantively flawed due to the subsequent bad debt[cite: 1]. A major legal obstacle was the doctrine of kōteiryoku (公定力), the binding force of administrative acts[cite: 1]. This doctrine holds that an administrative act, even if it contains defects, is treated as legally valid and effective unless and until it is officially revoked by the administrative agency itself or overturned through formal legal proceedings (e.g., an administrative lawsuit)[cite: 1].

Despite the reassessment not having been formally revoked by either the tax authority or through prior litigation, X chose to sue the State directly for the return of the approximately 240,000 yen, framing the claim as one of unjust enrichment (futō ritoku - 不当利得)[cite: 1]. The lower courts, both the first instance and the appellate court, found in favor of X[cite: 1]. The State then appealed to the Supreme Court[cite: 1].

The Supreme Court's Judgment (March 8, 1974): A Path to Fairness

The Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, dismissed the State's appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' decisions in favor of X[cite: 1]. The Court's reasoning provided a nuanced pathway to achieving a just outcome in a situation where formal administrative processes and legislative remedies were lacking.

The key points of the Supreme Court's rationale were as follows:

- Initial Validity but Subsequent Loss of Premise: The Court acknowledged that an administrative act like a tax assessment, once legally and validly established, does not retroactively become illegal or void merely due to a subsequent event like a bad debt[cite: 1]. However, it emphasized that the premise of taxation under the rights- 확정 principle is the eventual actual receipt of the income[cite: 1]. When the debt corresponding to the accrued income becomes uncollectible, this underlying premise of the taxation is lost[cite: 1].

- Violation of Income Tax Essence and Fairness: To allow the tax authority to exercise its collection powers based on the original assessment, or to retain taxes already collected, despite the loss of this taxation premise, would run counter to the fundamental nature of income tax, which aims to tax actual economic gain[cite: 1]. Furthermore, it would create an unjustifiable imbalance in relief measures when compared to how bad debts from business income were treated[cite: 1]. The Court stated that the law could not be interpreted as condoning such a result[cite: 1].

- Tax Authority's Duty to Correct and Lack of Taxpayer Remedy: Ideally, the income tax system anticipates that the tax authority, upon ascertaining the facts of a subsequent bad debt, would make the necessary corrections[cite: 1]. This would involve the tax authority itself determining the existence and amount of the bad debt, recalculating the taxable income and tax amount for the original year as if the uncollectible amount had never been income, and then revoking all or part of the initial tax assessment[cite: 1]. If the tax had already been collected, the corresponding amount would then be refunded to the taxpayer[cite: 1]. The Court viewed such corrective action as being legally expected and required of the tax authority once the bad debt became known[cite: 1]. However, a critical factor in X's case was that the old Income Tax Act provided no specific right for the taxpayer to demand such corrective measures from the tax authority[cite: 1].

- The "Objectively Clear" Condition for Direct Unjust Enrichment: The Court considered that the primary reason for entrusting the determination of taxable income and tax amounts to the tax authority's judgment is the technicality and complexity involved in tax collection[cite: 1]. However, if the occurrence of the bad debt and its amount are objectively clear (kyakkanteki ni meihaku - 客観的に明白) to the extent that it does not require any special discretionary judgment by the tax authority, and if there is no rational necessity to reserve this determination for the tax authority, then it would be grossly unfair and contrary to the principles of justice and equity to require the taxpayer to endure the tax burden simply because the tax authority has not taken corrective action[cite: 1].

- Consequence: Tax Becomes "Without Legal Cause": In such specific circumstances—where the bad debt is objectively clear and the taxpayer lacks other avenues for correction—the tax authority or the State can no longer assert the validity of the original tax assessment against the taxpayer to the extent of the bad debt[cite: 1]. Consequently, the State cannot lawfully collect taxes based on that portion of the assessment. More importantly for X's case, any tax already collected on this basis is deemed to be an enrichment without legal cause (hōritsujō no gen'in o kaku ritoku - 法律上の原因を欠く利得) and must be returned to the taxpayer[cite: 1].

Applying this to X's case, the Supreme Court found that the interest and damages X had waived through the court settlement were indeed objectively clear in their existence and amount, and that there was no reasonable need for the tax authority to exercise further discretionary judgment on this matter[cite: 1]. Therefore, the approximately 240,000 yen collected corresponding to this bad debt was to be returned by the State to X[cite: 1].

Unpacking "Without Legal Cause" in Public Law

The Civil Code of Japan, in Article 703, defines unjust enrichment: "A person who has benefited from the property or labor of others without legal cause, and has thereby caused loss to others, shall assume an obligation to return that benefit, to the extent the benefit still exists." [cite: 1] While this principle is generally accepted as applicable to public law relationships, the critical question in cases like X's is what constitutes "without legal cause," especially when a formal administrative act (the tax assessment) underlies the State's enrichment[cite: 1].

Scholarly debate has offered several perspectives on when a tax collected under an unrevoked, but substantively flawed, assessment can be considered "without legal cause" for the purposes of an unjust enrichment claim[cite: 1]:

- The Traditional View: This view holds that "without legal cause" applies only if the administrative act is null and void from its inception or has been officially revoked due to illegality[cite: 1]. If the assessment stands with kōteiryoku, it provides a "legal cause," precluding an unjust enrichment claim[cite: 1].

- The Subsequent Partial Invalidity View: This theory suggests that a subsequent event like a bad debt can cause the original tax assessment to become retroactively partially invalid to the extent of the uncollectible income[cite: 1]. This partial invalidity would mean that kōteiryoku is lost for that portion, thus establishing an absence of "legal cause"[cite: 1]. While aligning with general unjust enrichment principles and kōteiryoku, this approach has raised concerns that deeming an assessment partially invalid could complicate related procedures, such as those for collecting delinquent taxes[cite: 1].

- The Exceptional Unjust Enrichment View: This approach, emphasizing the specific, often unique, circumstances of a case, allows for an unjust enrichment claim as an exception, even while formally acknowledging the continued validity and kōteiryoku of the tax assessment[cite: 1]. It effectively disconnects the assessment's formal validity from the determination of "legal cause" for unjust enrichment purposes[cite: 1]. This has been criticized by some as an anomaly from the perspective of pure unjust enrichment theory, which typically links "legal cause" directly to the validity of the underlying act or transaction[cite: 1].

- The Outside Kōteiryoku's Scope View: This perspective argues that the issue arising from a subsequent event (like a bad debt) falls outside the objective scope of the original assessment's kōteiryoku[cite: 1]. Alternatively, it posits that the "blocking effect" of the administrative act does not extend to matters upon which the administrative authority made no determination at the time of the original act (i.e., the subsequent bad debt)[cite: 1]. Thus, for this subsequent aspect, there is no "legal cause" from the outset[cite: 1]. A criticism of this view is that it might necessitate a new administrative determination for every subsequent event, which could be overly circuitous[cite: 1].

The Supreme Court's 1974 judgment explicitly stated that "an assessment, once legally and validly established, does not retroactively become illegal or void merely due to a subsequent bad debt." [cite: 1] Yet, it permitted the unjust enrichment claim. The Court reasoned that allowing the State to retain the tax, given the loss of the taxation's premise and the lack of alternative remedies for the taxpayer, would violate the "essence of income tax" and principles of fairness, leading to the conclusion that the State could no longer assert the assessment's validity for the affected portion[cite: 1]. This inability to assert validity then rendered the collected tax "without legal cause." [cite: 1] The commentary on this case suggests that the Supreme Court's approach has elements that could align with either the third (exceptional unjust enrichment) or fourth (outside kōteiryoku's scope) theories[cite: 1]. The Court's detailed discussion of the taxpayer's lack of other remedies and its emphasis on the "objectively clear" nature of the bad debt might lean towards an exceptional, fairness-driven approach (Theory 3)[cite: 1]. The "objectively clear" condition might also serve to bolster Theory 4 by suggesting that no genuine administrative discretion was needed for the subsequent event, thus bypassing the rationale for kōteiryoku's full application[cite: 1].

The "Objectively Clear" Threshold

The condition that "the occurrence of the bad debt and its amount are objectively clear... and there is no rational necessity to reserve this determination for the tax authority" played a pivotal role in the Supreme Court's reasoning[cite: 1]. This threshold allowed the Court to sidestep the full implications of kōteiryoku without formally invalidating the original assessment. It recognized a situation where the substantive injustice was manifest and did not require the tax authority's specialized judgment to be apparent.

However, legal commentary has pointed out that this "objectively clear" standard could itself become a high bar for taxpayers to meet[cite: 1]. It was even suggested that in X's specific case, asserting that the bad debt was "objectively clear" might have been debatable, potentially narrowing the scope of relief in future cases if interpreted too strictly[cite: 1].

Evolution of the Legal Landscape

The specific factual matrix of X's case—particularly the absence of a statutory mechanism for demanding corrective action for non-business bad debts under the old Income Tax Act—is less likely to be replicated today[cite: 1]. Amendments to the Income Tax Act since 1962 have introduced procedures for taxpayers to seek corrections or refunds in situations involving subsequent changes to income[cite: 1]. Furthermore, significant reforms to the Administrative Case Litigation Act in 2004 introduced new types of actions, such as non-applicant type duty-imposition lawsuits (非申請型の義務付け訴訟), which generally allow taxpayers to sue to compel the tax authority to take necessary corrective measures, even if a specific procedure is not explicitly provided for the exact circumstance[cite: 1]. These developments have broadened the avenues available to taxpayers facing similar issues[cite: 1].

Despite these legislative improvements reducing the likelihood of the exact same remedial vacuum, the Supreme Court's judicial technique demonstrated in this 1974 case—that of restricting a party's ability to assert the full validity or effect of an administrative act in specific, compelling circumstances to achieve a just outcome between the parties involved—has reappeared in subsequent jurisprudence in other contexts[cite: 1]. Therefore, the fundamental problem of reconciling administrative finality with substantive justice, which this judgment addressed, remains a pertinent theme in administrative law[cite: 1].

It is also worth noting a later Supreme Court case (July 14, 2011) involving a different factual scenario: a business had obtained a designation to provide long-term care services through fraudulent means, and a city sought the return of care fees it had paid out[cite: 1]. The Supreme Court denied the city's unjust enrichment claim, reasoning that because the prefectural governor's designation had not been revoked and the flaws in the designation were not severe enough to render it automatically void, there was still a "legal cause" for the payments[cite: 1]. This decision appears more aligned with the traditional view (Theory 1) regarding "legal cause"[cite: 1]. However, the factual context was distinct from the 1974 tax case (a claim by a government entity against a citizen, rather than vice versa)[cite: 1]. Moreover, a supplementary opinion by one of the justices emphasized that since the act of designation was discretionary, allowing an unjust enrichment claim to recover the fees would, in substance, produce the same outcome as revoking the designation, thereby sidestepping the discretionary nature of the revocation power—a key consideration related to the structure of the specific law in question[cite: 1].

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 8, 1974, decision stands as a significant moment in Japanese administrative and tax law. It ingeniously carved out a path for taxpayers to claim unjust enrichment against the State for taxes paid on income that subsequently failed to materialize, even when the original assessment remained formally intact. This was achieved by focusing on the fundamental nature of income tax, the principles of justice and equity, the lack of alternative remedies for the taxpayer at the time, and the crucial condition that the facts rendering the tax unjust (the bad debt and its amount) were "objectively clear." While subsequent legislative reforms have addressed some of the specific procedural gaps present in this case, the judgment's underlying approach to balancing the binding force of administrative acts with the imperative of substantive fairness continues to resonate, showcasing the judiciary's role in adapting legal principles to ensure just outcomes in complex administrative contexts.