Tax Withholding Under Duress: Japanese Supreme Court on Employer's Duty When Wages Are Seized

Date of Judgment: March 22, 2011

Case Name: Claim for Reimbursement (平成21年(受)第747号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

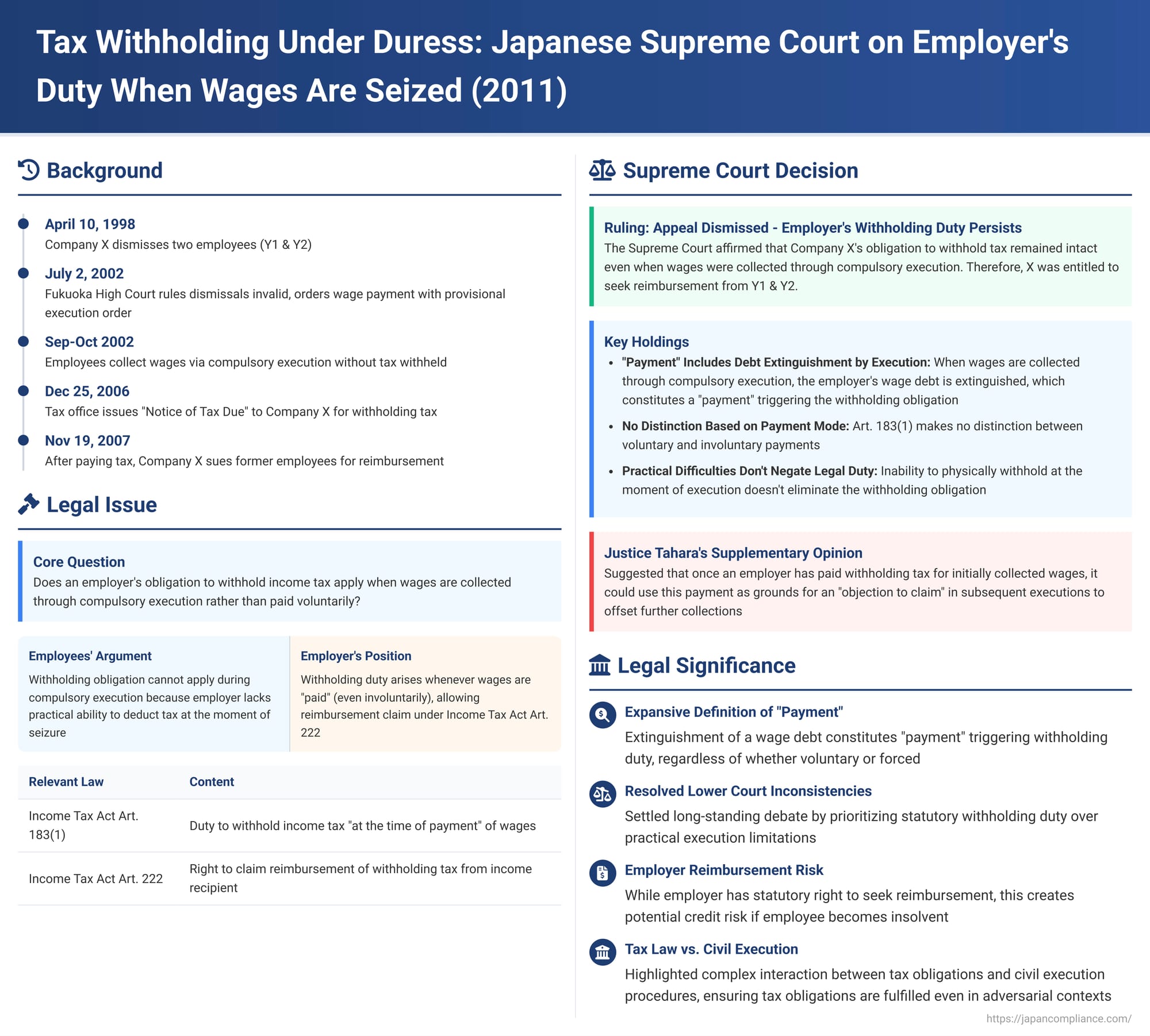

In a significant decision on March 22, 2011, the Supreme Court of Japan clarified an employer's obligation to withhold income tax at source even when wages are not paid voluntarily but are instead collected by employees through compulsory court execution proceedings. The Court held that the employer's withholding duty persists in such scenarios, with the employer then having a statutory right to seek reimbursement from the employees for the tax remitted to the government.

The Wrongful Dismissal and Compulsory Wage Collection

The plaintiff, Company X, had dismissively terminated two of its employees, Y1 and Y2, on April 10, 1998. The employees challenged the dismissals, filing a lawsuit for a declaration of their invalidity and for payment of unpaid wages. On July 2, 2002, the Fukuoka High Court, Miyazaki Branch, ruled in favor of the employees, confirming the dismissals were invalid and ordering Company X to pay "the subject wages" due from the date of dismissal onwards. This judgment included a "provisional execution order" (仮執行宣言 - kari shikkō sengen), allowing the employees to seek enforcement of the wage payment even while further appeals might be pending. Company X's subsequent appeal to the Supreme Court concerning the dismissal was ultimately dismissed on July 1, 2005, making the High Court's judgment final and binding.

Armed with the provisionally enforceable High Court judgment, Y1 and Y2 initiated compulsory execution proceedings in the Miyazaki District Court to collect the wages owed to them for the period from May 11, 1998, to August 31, 2002. In response, on September 27, 2002, Company X deposited an amount with the court execution officer. This amount corresponded to the employees' claim less certain deductions X considered applicable, including estimated withholding income tax, the employees' share of social insurance premiums, and their share of private pension contributions (collectively, "the First Deduction Amount").

However, on October 3, 2002, Y1 and Y2 applied to the court for an additional seizure order to recover the First Deduction Amount, arguing they were entitled to the gross amount of wages as per the judgment. On the same day, Company X deposited this additional sum with the court execution officer. Over the period extending to July 2005, Y1 and Y2 initiated a total of eight rounds of compulsory execution for the subject wages. By that date, Company X had paid the full gross amount of the subject wages (accrued up to June 30, 2005) to the court execution officer, partly through these compulsory seizures and partly through payments it made voluntarily to the execution officer to satisfy the judgment.

Subsequently, on December 25, 2006, the Miyazaki Tax Office Head issued a "notice of tax due" (nōzei no kokuchi) to Company X. This notice was for the income tax that, according to the tax office, X should have withheld at source from the subject wages paid to Y1 and Y2 (as per Article 221 of the Income Tax Act and Article 36, paragraph 1, item 2 of the General Act of National Taxes). Company X paid this demanded amount of withholding income tax ("the subject paid tax amount") to the government.

Having paid this tax, Company X then turned to its former employees. On October 6, 2007, X formally demanded reimbursement from Y1 and Y2 for the subject paid tax amount, asserting a statutory right of recourse under Article 222 of the Income Tax Act. When the former employees did not comply, Company X filed the present lawsuit against them on November 19, 2007, seeking reimbursement of the withholding tax it had paid, plus delay damages.

The first instance court (Miyazaki District Court) ruled in favor of Company X. It held that an employer's obligation to withhold income tax under Article 183, paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act arises whenever wages are paid, irrespective of whether the payment is made voluntarily or is collected through compulsory execution. Since Company X was compelled by the tax office to pay the withholding tax, it was entitled to seek reimbursement from Y1 and Y2 under Article 222. The Fukuoka High Court, Miyazaki Branch, affirmed this decision, dismissing the appeal by Y1 and Y2. The employees then appealed to the Supreme Court, their principal argument being that the withholding obligation should not arise when wages are collected via compulsory execution, as the employer lacks the practical ability to "withhold" (i.e., deduct) at the moment of such an involuntary "payment."

The Legal Question: Withholding Duty When Payment is Forced?

The central legal question before the Supreme Court was: Does an employer's obligation to withhold income tax at source from wage payments, as stipulated by Article 183, paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act ("at the time of payment" - その支払の際 sono shiharai no sai), still arise when those wages are not paid voluntarily by the employer but are instead collected by the employees through compulsory court execution proceedings based on a provisionally enforceable judgment ordering such wage payment? And if such an obligation does arise, can the employer, who might be practically unable to deduct the tax at the moment of such a forced "payment," still be held liable for remitting the withholding tax to the government and subsequently seek reimbursement from the employee under Article 222?

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Withholding Obligation Stands

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by Y1 and Y2, thereby upholding the lower courts' decisions. The Court affirmed that the employer (Company X) did have a withholding tax obligation even when the wages were collected through compulsory execution, and consequently, X was entitled to seek reimbursement from the employees for the tax it had paid to the government.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- "Payment" Includes Debt Extinguishment by Compulsory Execution: Article 183, paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act obligates a person making payments of salary, wages, etc., to withhold income tax "at the time of payment" and remit it to the government. The Supreme Court held that even when an employer (the "payer") has wages collected from it by an employee through compulsory execution based on a judgment ordering such payment, this act of collection by the employee results in the extinguishment of the employer's underlying wage payment obligation (上記の者の給与等の支払債務は消滅する - jōki no mono no kyūyo tō no shiharai saimu wa shōmetsu suru).

The Court reasoned that this extinguishment of the debt, even though effected through compulsory means, constitutes a "payment" (shiharai - 支払) of wages within the meaning of Article 183, paragraph 1. - Statute Makes No Distinction Based on Mode of Payment: The Court further noted that Article 183, paragraph 1 makes no distinction whatsoever as to whether the "payment" of wages is made voluntarily by the employer or is effected through compulsory execution proceedings. Since the legal effect (extinguishment of the wage debt) is the same, the withholding obligation arises in both scenarios.

- Practical Inability to "Withhold" at the Moment of Execution Does Not Negate the Underlying Duty: The Supreme Court acknowledged the employees' argument that in a compulsory execution scenario, the employer cannot physically "withhold" or deduct the income tax from the amount being seized by the court execution officer, as the execution is typically for the gross amount awarded by the judgment. However, the Court stated that this practical difficulty in effecting a contemporaneous deduction does not negate the employer's legal obligation to remit the corresponding withholding tax amount to the government.

The law provides a recourse for the employer in such situations: Article 222 of the Income Tax Act allows a withholding agent who has paid withholding tax to the government (even if they were unable to actually deduct it from the payment made to the employee at that specific moment) to then claim reimbursement of that remitted tax amount from the employee (the person who should have ultimately borne the tax). Therefore, the employees' argument about the impossibility of physical deduction at the moment of compulsory payment did not alter the Court's interpretation of the employer's primary withholding (and remittance) duty.

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded that the lower courts' judgment, which found Company X liable for withholding income tax on the wages paid via compulsory execution and therefore entitled to seek reimbursement from Y1 and Y2, was correct and should be upheld.

Justice Mutsuo Tahara's Supplementary Opinion:

Justice Tahara provided a supplementary opinion that, while concurring with the majority, offered further practical insights:

- He reiterated that the withholding obligation arises at the time of actual payment; the mere determination or fixing of an employee's wage claim does not, by itself, trigger the employer's duty to withhold.

- This principle applies equally to payments made through compulsory execution.

- Since civil execution procedures typically do not have a built-in mechanism for the employer (execution debtor) to deduct withholding tax before the funds are collected by the employee (execution creditor), the practical outcome is that the employee receives the gross amount via execution. The employer must then separately remit the applicable withholding tax to the government and subsequently exercise its right of reimbursement against the employee under Article 222.

- Justice Tahara also addressed a potential issue in cases of multiple rounds of compulsory execution for wages. He suggested that once an employer has paid withholding tax related to wage amounts collected in an initial round of execution, the employer could then assert this paid tax amount as a ground for an "objection to claim" (請求異議 - seikyū igi) in any subsequent execution proceedings by the employee for later wage installments. This would allow the employer to argue that the amount being claimed by the employee in later executions should be reduced by the withholding tax already paid to the government by the employer on the earlier collected installments.

Analysis and Implications

The Supreme Court's 2011 decision has several important implications for employers and employees in Japan concerning income tax withholding:

- Broad Definition of "Payment" for Withholding Purposes: The ruling establishes that the legal extinguishment of a wage debt is considered a "payment" that triggers the employer's withholding tax obligation, regardless of whether this extinguishment occurs through voluntary settlement or involuntary means like court-ordered compulsory execution. This focuses on the legal and economic effect of the debt satisfaction rather than the voluntariness of the employer's action.

- Resolution of Conflicting Lower Court Precedents: This decision resolved a long-standing debate and inconsistency in Japanese lower court judgments. Some earlier rulings (e.g., a Takamatsu High Court judgment from 1969) had denied the employer's withholding obligation in compulsory execution scenarios, primarily due to the practical impossibility of the employer "withholding" or deducting tax at the point of seizure by a court officer. The Supreme Court's decision prioritizes the underlying statutory duty to ensure tax is collected on wage payments.

- Employer's Burden and Recourse (Reimbursement Risk): While Article 222 of the Income Tax Act provides employers with a statutory right to seek reimbursement from employees for withholding tax remitted to the government, this still places an administrative burden and a potential credit risk on the employer. If the employee becomes insolvent or otherwise unable to repay, the employer may bear the ultimate financial loss. Justice Tahara's supplementary opinion regarding raising an objection in subsequent execution proceedings offers a potential mechanism for employers to mitigate this risk in ongoing, installment-based wage collections.

- Interaction Between Tax Law and Civil Execution Law: The case highlights the complex interplay between tax obligations (the employer's statutory duty to withhold and remit) and civil execution procedures (the employee's right to enforce a judgment for the gross amount of wages owed). The Supreme Court's decision effectively ensures that the tax obligation is fulfilled, even if it requires a two-step process (collection by employee, then reimbursement claim by employer).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2011 judgment in this case provides a definitive clarification that an employer's legal obligation to withhold income tax on wages and remit it to the government persists even when those wages are collected by employees through compulsory court execution. The legal act of "payment," which triggers the withholding duty, is interpreted to include the extinguishment of the wage debt through such involuntary means. While direct deduction by the employer at the moment of seizure by a court officer might be practically impossible, the employer must still fulfill its remittance obligation to the tax authorities and is then entitled by statute to seek reimbursement of that tax amount from the employee. This ruling prioritizes the integrity and comprehensive application of the income tax withholding system, while providing a (though potentially cumbersome for the employer) statutory mechanism for the employer to recover the remitted tax from the employee who ultimately bears the income tax liability.