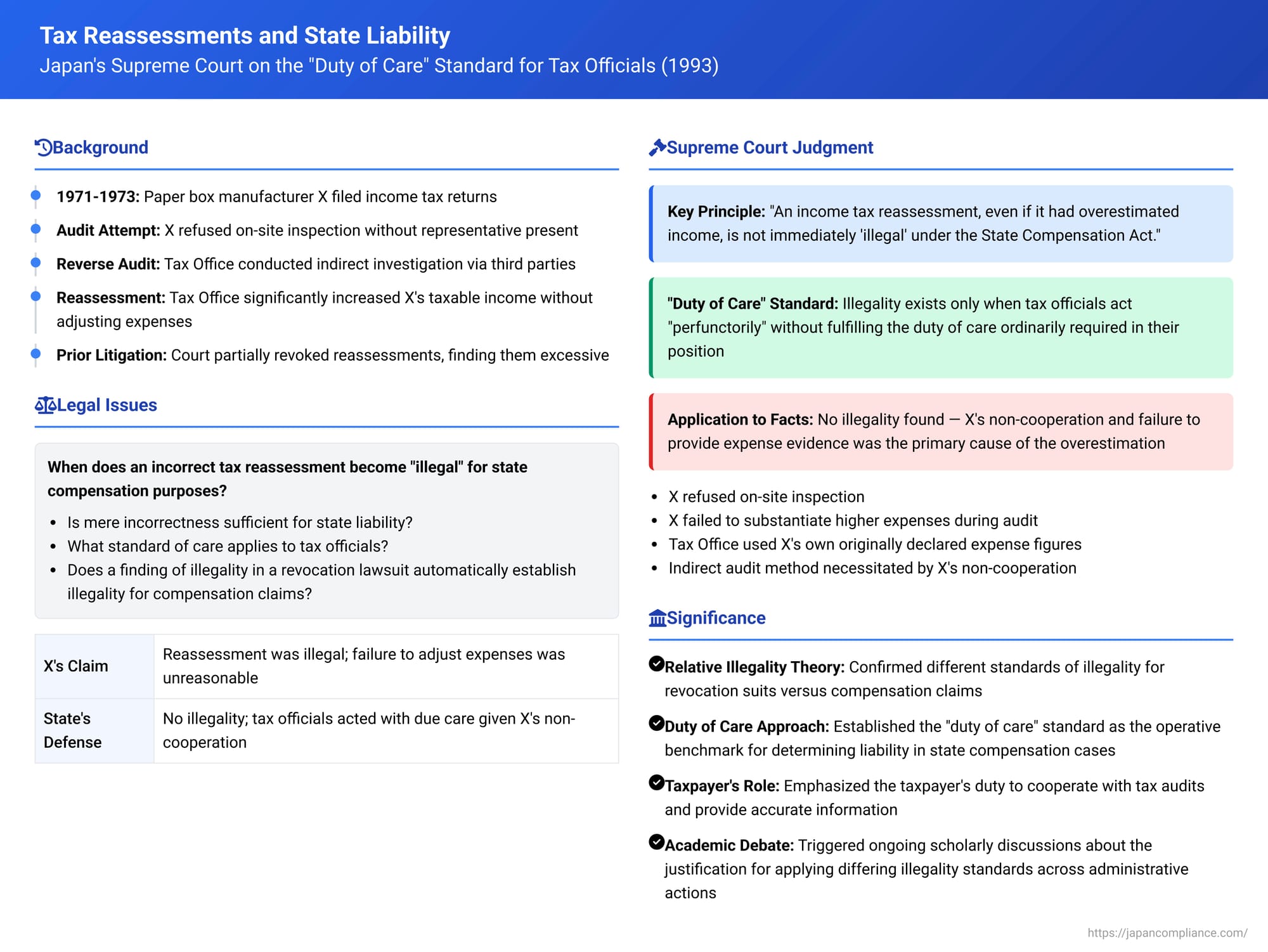

Tax Reassessments and State Liability: Japan's Supreme Court on the "Duty of Care" Standard for Tax Officials

Date of Judgment: March 11, 1993

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

On March 11, 1993, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment addressing the conditions under which an income tax reassessment by tax authorities, even if subsequently found to be partially incorrect and reduced by a court in a revocation lawsuit, can be deemed "illegal" for the purposes of a state compensation claim for damages. This case, involving a paper box manufacturer and the Nara Tax Office, is pivotal for its clarification of the standard for establishing state liability in such tax-related matters. The Court emphasized a "duty of care" standard for tax officials and, in doing so, reinforced a distinction often drawn in Japanese administrative law between the type of illegality that warrants the administrative revocation of a tax assessment and the type of illegality that gives rise to a claim for monetary damages against the state.

I. The Disputed Tax Reassessment: A Manufacturer's Tale

The case centered on the income tax assessments of X, a manufacturer and processor of paper boxes primarily used for product packaging.

The Tax Filings and Subsequent Audit:

X had filed income tax returns for three consecutive years (Showa 46-48, which correspond to 1971-1973), reporting specific amounts of taxable income for each of these years. For example, for the Showa 48 tax year (1973), X had declared an income of JPY 968,098. Following these filings, the Nara Tax Office initiated an audit to verify the accuracy of X's declared income. As part of this audit, tax officials made several attempts to visit X's business premises to conduct an on-site inspection of X's books, financial records, and other relevant documents.

Non-Cooperation by the Taxpayer:

A significant issue arose during this audit process. X refused to allow the tax officials to conduct their on-site inspection unless a representative from the Nara Democratic Society of Commerce and Industry (a type of business support and advocacy association) was permitted to be present during the audit. The tax officials did not agree to this condition, and as a result of this standoff, they were unable to carry out their planned direct examination of X's business records at X's premises.

The "Reverse Audit" and Subsequent Reassessment by the Tax Office:

Faced with this lack of cooperation and the inability to directly inspect X's primary records, the Head of the Nara Tax Office resorted to what is known in Japan as a "reverse audit" (hanmen chōsa). This investigative technique involves gathering information about a taxpayer's financial activities indirectly, typically by contacting and examining the records of third parties with whom the taxpayer does business, such as customers, suppliers, and financial institutions (e.g., investigating X's customer transactions and bank account activity).

Based on the information obtained through this indirect "reverse audit" method, the Tax Office Head concluded that X's actual income for the years in question was significantly higher than what X had originally declared. Consequently, the Tax Office Head issued corrective reassessments (kōsei shobun) for all three years, substantially increasing X's determined taxable income. For the Showa 48 tax year, as an illustration, X's taxable income was reassessed upwards from the initially declared JPY 968,098 to a much larger JPY 6,464,320.

A critical aspect of these reassessments, which became a central point of contention, was that when the Tax Office increased X's gross income figures based on its reverse audit, it continued to use the exact same figures for necessary business expenses that X had originally declared in the initial tax filings. The Tax Office did not make any corresponding upward adjustment to the allowable business expenses to match the substantially increased income figures it had calculated.

II. Prior Litigation: The Revocation Lawsuit Challenging the Reassessments

X did not accept these significantly higher tax reassessments and chose to challenge their validity through the administrative litigation process.

Initial Challenge and District Court Ruling:

After exhausting preliminary administrative appeal procedures within the tax administration (such as filing an objection with the tax office), X initiated a lawsuit in court seeking the revocation (torikeshi soshō) of the Nara Tax Office Head's reassessment dispositions for the three disputed years. The Nara District Court, which heard the case at first instance, dismissed X's claims, thereby upholding the Tax Office's reassessments.

Success at the High Court:

X appealed the District Court's adverse decision to the Osaka High Court. On appeal, the Osaka High Court partially sided with X. While the High Court agreed with the Tax Office that X's income was indeed higher than what X had initially declared, it also found that the Tax Office's subsequent reassessments had overstated X's taxable income. A key reason for this finding was the High Court's acknowledgment that X was, in fact, entitled to higher deductions for necessary business expenses than had been allowed in the Tax Office's reassessments (which, as noted earlier, had controversially used X's originally declared, and lower, expense figures despite significantly increasing the income figures).

As a result of these findings, the Osaka High Court issued a judgment that partially revoked the Tax Office's reassessment dispositions. For the Showa 48 tax year, for example, the High Court reduced the reassessed taxable income from the Tax Office's figure of JPY 6.46 million to a lower figure of JPY 1.57 million. This judgment of the Osaka High Court in the revocation lawsuit became final and conclusive, as no further appeals were successfully pursued in that particular line of litigation. This meant that, for legal purposes, the Tax Office's original reassessments were confirmed to have been partially excessive and incorrect.

III. The State Compensation Lawsuit: Seeking Damages for an Allegedly "Illegal" Reassessment

Following this partial victory in the revocation lawsuit (which established that the tax reassessments were, to some extent, erroneous), X initiated a new and separate legal action. This time, X filed a claim for monetary damages against the State of Japan (Y), basing this claim on Article 1, paragraph 1 of Japan's State Compensation Act.

X's Argument for Damages:

X contended that the Nara Tax Office Head's original reassessment dispositions, which had now been partially overturned by a final court judgment, were not merely incorrect but were "illegal" within the specific meaning of the State Compensation Act. The core of this alleged illegality, according to X, stemmed from the Tax Office's unreasonable failure to consider that if a taxpayer's gross income is found to be higher, their necessary business expenses would naturally and logically also be expected to increase. X argued that the Tax Office's failure to make any upward adjustment to the expense figures when it substantially increased the income figures was a decision made either with intent (to unfairly maximize tax) or through negligence (a failure to exercise proper care and judgment). As a result of this allegedly illegal reassessment, X claimed to have suffered various damages, including consolation money (for mental distress caused by the ordeal), business losses, and the attorney's fees incurred in the course of the prior, successful revocation lawsuit.

Lower Court Rulings in the Damages Suit:

- District Court (Nara District Court): The District Court, when hearing this new damages claim, dismissed X's lawsuit.

- High Court (Osaka High Court): X appealed this dismissal. On appeal, the Osaka High Court partially sided with X regarding the damages claim. It found that the Tax Office's reassessment for the Showa 48 tax year, specifically, was indeed illegal for the purposes of state compensation. The High Court reasoned that, for that year, "the officials in charge of the disposition grossly violated the duty that should ordinarily be fulfilled in their official position." Based on this finding, the High Court awarded X damages, which included an amount for consolation money and a portion of the attorney's fees X had incurred. It was this High Court judgment in the damages suit, which had found the State liable for the Showa 48 reassessment, that the State (Y) then appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

B. The Supreme Court's Standard for Determining "Illegality" in State Compensation Claims Arising from Tax Reassessments:

The Supreme Court of Japan, in its judgment dated March 11, 1993, overturned the Osaka High Court's decision (which had found in favor of X for the Showa 48 reassessment) and ultimately ruled entirely in favor of the State, dismissing X's damages claim. The linchpin of the Supreme Court's reasoning was its careful articulation and application of the standard for determining when a tax reassessment crosses the threshold of "illegality" as that term is used in Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act:

- The Court stated: "An income tax reassessment made by a Tax Office Head, even if it had overestimated the amount of income, is not to be immediately evaluated as having an illegality as referred to in Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act. It is appropriate to understand that such a reassessment receives such an evaluation [of illegality for compensation purposes] only if there are circumstances under which it can be recognized that the Tax Office Head, in the process of collecting materials and, based on these, certifying and judging the facts relevant to tax liability, made the reassessment perfunctorily (manzen to kōsei o shita) without fulfilling the duty of care that should ordinarily be fulfilled in his official position." This establishes a standard that looks beyond mere error to a more serious failing in the conduct of the tax official.

C. Application of this "Duty of Care" Standard to the Specific Facts of X's Case:

The Supreme Court then meticulously applied this "duty of care" standard to the actions and decisions of the Nara Tax Office Head in X's particular situation:

- X's Initial Underreporting of Necessary Expenses: The Court began by noting a crucial fact established in the prior litigation: X, in filing the original income tax returns for the contested years, had themselves declared amounts for necessary business expenses that were later found to be less than the accurate amounts (as determined by the Osaka High Court in the revocation suit).

- X's Non-Cooperation with the Tax Audit: Critically, the Supreme Court highlighted X's lack of cooperation during the tax audit process. It was a fact that before the reassessments were issued, tax officials had explicitly informed X that their preliminary investigation had already revealed the existence of income exceeding the amounts X had declared in their initial filings. The officials had urged X to cooperate with a full audit to clarify the situation. Despite this, X had refused to allow an on-site inspection of their books and records under the conditions requested by the tax office (i.e., without the presence of the Democratic Society of Commerce and Industry representative).

- Opportunity Provided to X to Substantiate Higher Expenses: The Supreme Court emphasized that, during the audit process leading up to the reassessments, X had been given an opportunity to proactively present evidence or make arguments regarding the correct and potentially higher amount of their necessary business expenses. This was particularly relevant given that X had been informed that undisclosed income had already been found. However, X failed to take this opportunity to provide further substantiation for higher expense claims before the reassessments were finalized by the Tax Office.

- Tax Office's Basis for Determining Expenses in the Reassessment: In light of X's ongoing non-cooperation and their failure to provide any additional information or evidence regarding their necessary expenses, the Nara Tax Office Head proceeded to calculate the reassessed taxable income by using the (admittedly understated) necessary expense figures that X themselves had originally declared in their initial tax returns.

- Primary Cause of the Subsequent Income Overestimation: Based on these facts, the Supreme Court concluded that the overestimation of X's taxable income in the Tax Office's reassessments (which was later corrected in the revocation suit) was primarily attributable to X's own actions and omissions. These included X's initial underreporting of necessary expenses in the tax filings, and, more significantly, X's subsequent failure to correct these figures or provide substantiation for higher expenses even when explicitly given the chance to do so during the audit process that preceded the reassessments.

- No Demonstrable Breach of Duty of Care by the Tax Office Head: Given these specific circumstances, particularly X's lack of cooperation and failure to provide necessary information, the Supreme Court found no evidence to suggest that the Nara Tax Office Head had failed to exercise the ordinary duty of care that would be expected of a tax official in such a situation. There was no indication that the reassessments had been made "perfunctorily" or with a reckless disregard for accuracy. The Tax Office had based its income figures on a "reverse audit" (a method necessitated by X's non-cooperation) and had, for the expense component, used the figures that X themselves had provided and had not subsequently amended or substantiated despite the opportunity.

- Conclusion on Illegality for State Compensation Purposes: Therefore, the Supreme Court held that even the reassessment for the Showa 48 tax year (which the Osaka High Court in the damages suit had found to be illegal for compensation purposes) did not constitute an "illegal" act within the specific meaning of Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act. The stringent conditions for establishing state liability in such cases—specifically, a perfunctory reassessment made without exercising ordinary professional care—were simply not met on the facts as presented.

IV. The "Relative Illegality" Theory and Its Implications for State Compensation

This Supreme Court judgment is a key and often-cited illustration of how Japanese courts, particularly the Supreme Court itself, frequently approach the concept of "illegality" differently when dealing with state compensation claims as compared to lawsuits that seek the mere revocation or annulment of an administrative act. This differential approach is often referred to by legal scholars in Japan as the theory of "relative illegality" or, sometimes, the "dualism of illegality" (ihō sōtai-setsu or ihō nigen-ron).

Two Main Theoretical Approaches to "Illegality" in Administrative Law:

- "Illegality Monism" or the "Absolute Illegality Theory" (ihō ichigen-setsu, ihō zettai-setsu): This theoretical approach posits that the concept of "illegality" should have a single, unified meaning across different types of legal actions that can be brought against the state or its administrative acts. According to this view, if an administrative act (such as a tax reassessment) is found to be "illegal" to a degree that warrants its revocation or annulment in an administrative lawsuit (typically a revocation suit, or torikeshi soshō in Japanese), then that same finding of "illegality" should automatically be sufficient to establish the "illegality" requirement for a subsequent state compensation claim brought under Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act. This perspective emphasizes that illegality fundamentally signifies a violation of the objective legal norms and procedural rules that govern the exercise of state authority.

- "Illegality Dualism" or the "Relative Illegality Theory" (ihō nigen-setsu, ihō sōtai-setsu): This alternative theoretical framework, which is widely considered to be the one predominantly adopted by the Japanese Supreme Court in many of its decisions, including the present 1993 tax case, holds that the concept of "illegality" in the context of state compensation claims can be, and often is, different from the concept of "illegality" that applies in the context of revocation suits. According to this dualist view, a revocation suit primarily examines whether an administrative act suffers from a flaw (substantive or procedural) that makes it contrary to law and thus renders it unenforceable or invalid going forward. In contrast, a state compensation suit is concerned with a different question: after harm has already occurred as a result of some state action, is it fair, just, and legally appropriate to shift the burden of that financial loss from the individual victim to the state (and thus, ultimately, to the taxpayers)? This latter determination, the theory suggests, might involve different or additional considerations, potentially leading to a distinct, and often stricter, standard of "illegality" that must be met before compensation can be awarded.

This Judgment's Clear Endorsement of "Relative Illegality" via the "Duty of Care Standard":

- The Supreme Court's reasoning in this 1993 tax reassessment case clearly aligns with, and indeed strongly endorses, the "relative illegality" theory. The Court explicitly stated that a tax reassessment, even if it is subsequently found to have overestimated a taxpayer's income (and was, in fact, partially revoked in a prior lawsuit for precisely that reason, thereby indicating "illegality" for revocation purposes), is not necessarily or not immediately to be deemed "illegal" for the distinct purposes of a state compensation claim.

- The Court then grounded its finding of no state compensation liability on the basis that such liability arises only when it can be shown that the tax official responsible for the reassessment has violated the "duty of care ordinarily required in their official position" and, furthermore, has made the reassessment "perfunctorily" (manzen to). This invocation of a specific "duty of care standard" (shokumu kōi kijun-setsu) as the operative benchmark for determining "illegality" in state compensation cases is a key mechanism through which the "relative illegality" theory is put into practice by the courts. It essentially introduces a significant fault-like element—a serious breach of an official's expected professional duties and diligence—into the very definition of "illegality" for the purpose of awarding compensation. This makes the standard for compensation distinct from, and often considerably more stringent than, the standard that might suffice for merely revoking or annulling the administrative act itself.

Precedents and the Generalization of the "Duty of Care Standard" in State Compensation Law:

- This "duty of care standard" for determining "illegality" in state compensation cases was not entirely novel to this 1993 tax judgment. The Supreme Court had employed similar reasoning and language in some earlier cases. However, those earlier instances often involved what might be considered special or unique categories of state activity, such as prosecutorial decisions regarding whether or not to indict a suspect (where a prosecutor's decision is generally not deemed illegal for compensation purposes merely because an acquittal ultimately results), or cases concerning alleged legislative inaction by the National Diet (where establishing liability for failure to legislate is exceptionally difficult).

- The particular significance of this 1993 judgment lies in its application of the "duty of care standard," and the concomitant "relative illegality" theory, to a much more typical and routine type of administrative disposition: a tax reassessment. In the years since this 1993 ruling, the Supreme Court has continued to apply this standard in a variety of other cases involving ordinary administrative activities, across different fields of government action. This suggests that the 1993 tax case played an important role in solidifying and perhaps generalizing the broader applicability of this approach to determining state compensation liability.

Academic Perspectives and Criticisms of the Prevailing Judicial Approach:

- Despite its consistent adoption by the Supreme Court, the general application of the "relative illegality" theory (particularly when it is operationalized through the "duty of care standard") to ordinary administrative dispositions has faced considerable criticism from many legal scholars in Japan.

- Lack of Strong Justification for Ordinary Acts: Critics argue that while applying a stricter standard of illegality for compensation purposes might be justifiable for unique or high-level state functions like legislation or core policy decisions (where broad discretion is involved), there is less compelling justification for applying such a heightened standard when dealing with ordinary administrative acts (like routine tax assessments or permit issuances) where the objective legal norms and procedural rules that govern the agency's authority are often relatively clear and well-defined.

- Upholding the Rule of Law: If state compensation lawsuits are understood to serve not only the private purpose of providing relief to individual victims but also the broader public purpose of upholding the rule of law and ensuring administrative legality by deterring unlawful official conduct, then it is undesirable for the fundamental concept of "illegality" to have different meanings or thresholds depending on whether a plaintiff is seeking the revocation of an act or monetary compensation for harm caused by it.

- Conflation of "Illegality" and "Negligence": A significant doctrinal criticism is that when the "duty of care standard" is used as the primary determinant of "illegality" for compensation purposes, the separate requirement of "negligence" (kashitsu), which is also explicitly stated as a condition for liability in Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act ("intentionally or negligently"), tends to become absorbed into, or made effectively redundant by, the illegality determination itself. Factors such as the taxpayer's non-cooperation in this specific case—which, under a "monist" view of illegality, might be considered more appropriately under the rubric of the taxpayer's own contributory negligence or as a factor negating the official's "negligence"—are instead factored into the court's determination of whether the official breached their duty of care (and thus, whether their action was "illegal" in the first place). While the ultimate outcome in terms of whether compensation is awarded or not might not always differ dramatically between the two theoretical approaches, the doctrinal pathway taken and the allocation of specific factual elements within the overall legal test are distinct. Critics of the "relative illegality" approach argue that there is little compelling need to complicate the illegality analysis with these fault-like considerations when they could be more straightforwardly and distinctly addressed under the separate "negligence" requirement of the statute.

An Alternative Scholarly Interpretation: Specificity to the Realm of Tax Administration:

- There is an alternative scholarly perspective that seeks to interpret the Supreme Court's reasoning in this 1993 judgment in a more limited way. This view suggests that the Court's approach might be best understood not as laying down a universally applicable rule for all ordinary administrative acts, but rather as a decision that was heavily influenced by, and perhaps should be confined to, the specific context and unique characteristics of tax administration. This perspective would argue that the strong emphasis in tax law on the taxpayer's primary duty of self-assessment and accurate declaration, and the correlative duty of cooperation with tax audits, might justify the Court's particular approach in this specific domain, without necessarily intending to generalize the "duty of care" standard for defining "illegality" to all other areas of administrative action. Some scholars also point out, as a further nuance, that the damages being claimed in this particular case were not primarily for direct financial loss caused by an overpayment of tax per se (as such overpayment would have ideally been rectified by the prior revocation suit and subsequent tax refunds), but rather for consequential harms such as mental distress and legal costs, which might invite a different analytical lens from the court.

V. Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's March 11, 1993, decision in this income tax reassessment case provides a critical and often-cited illustration of its prevailing approach to determining state compensation liability, particularly through its application of the "relative illegality" theory, operationalized by a "duty of care" standard for public officials.

The ruling makes unmistakably clear that an administrative act, such as a tax reassessment, being found incorrect or flawed enough to be partly revoked in one type of lawsuit (a revocation suit) does not automatically and necessarily render that same act "illegal" for the distinct purpose of claiming monetary damages in a subsequent state compensation suit. For state compensation liability to attach, the Supreme Court requires a more stringent showing: specifically, a demonstration that the official in question acted "perfunctorily" and, in doing so, breached the ordinary duty of care and diligence expected of someone in their official position.

By placing significant emphasis on the taxpayer's own role and responsibilities in providing accurate information and cooperating with tax audits, the Court ultimately found no such breach of duty by the tax authorities in this particular case, and consequently denied the taxpayer's claim for damages. This judgment continues to be a significant reference point in understanding the nuanced standards for state liability, the duties expected of public officials in Japan, and the important distinction between the review of administrative legality for annulment versus for compensation.